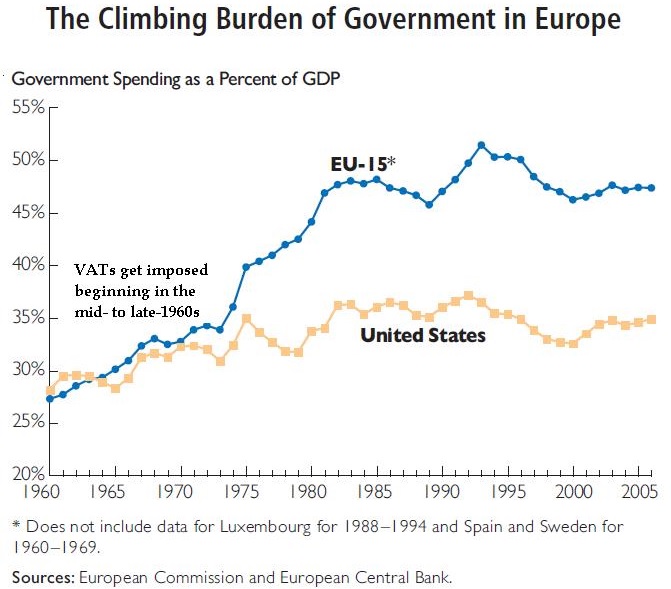

I already shared my thoughts about the value-added tax when discussing fiscal policy with an economist at the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise.

Here’s some of what I said about tax progressivity and the welfare state.

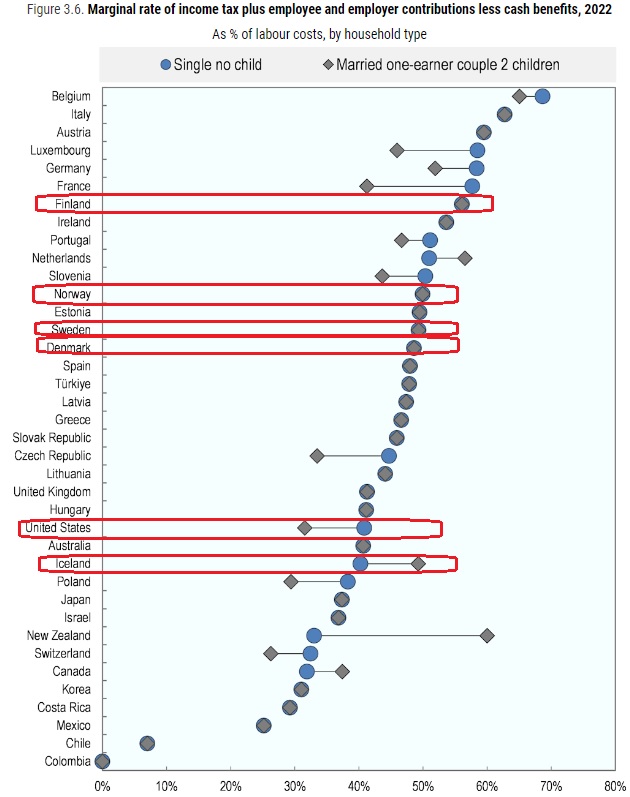

The bottom line is that the American tax system targets the rich. But that’s not the case in Sweden.

If you don’t believe me, let’s see what some left-of-center sources say.

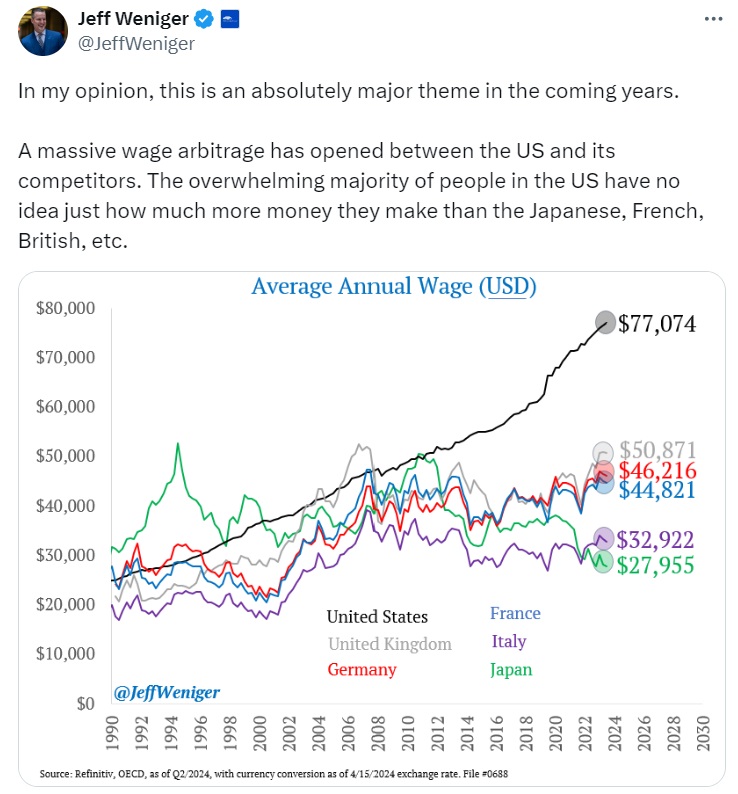

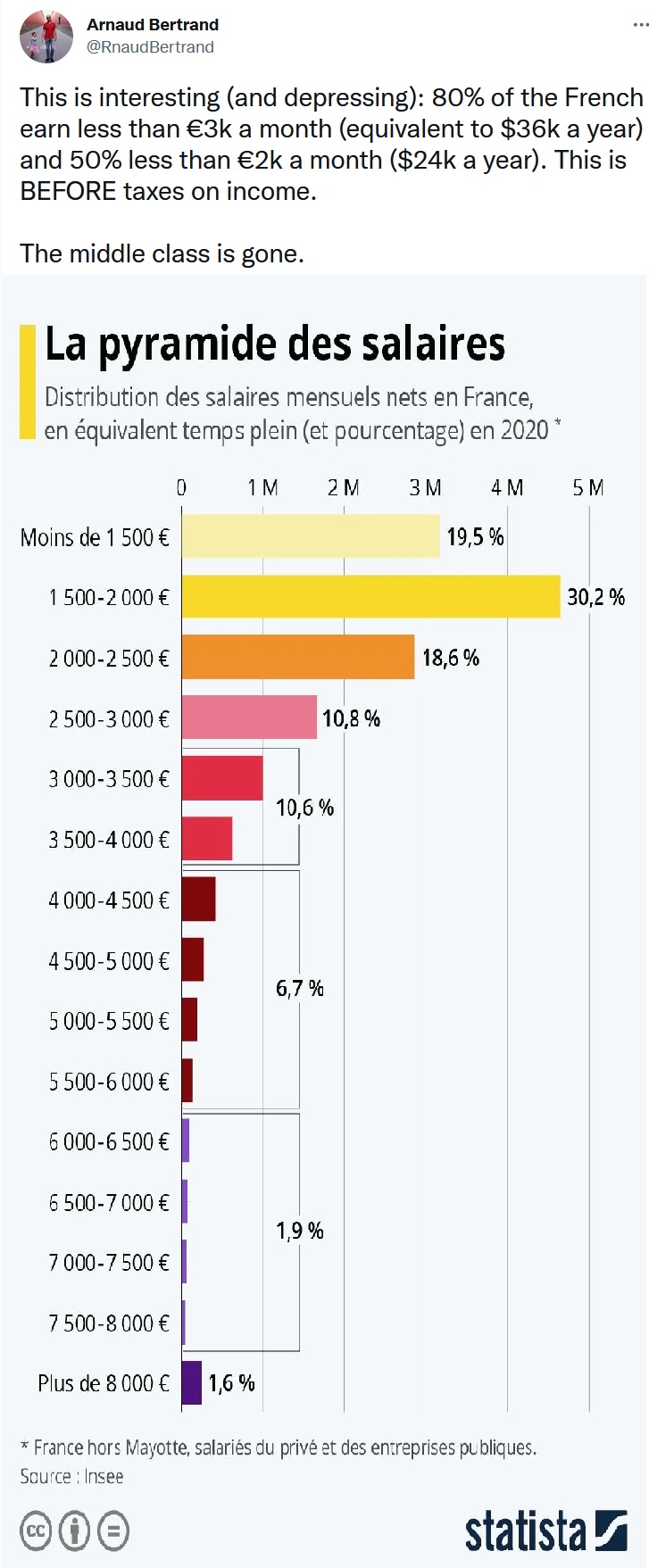

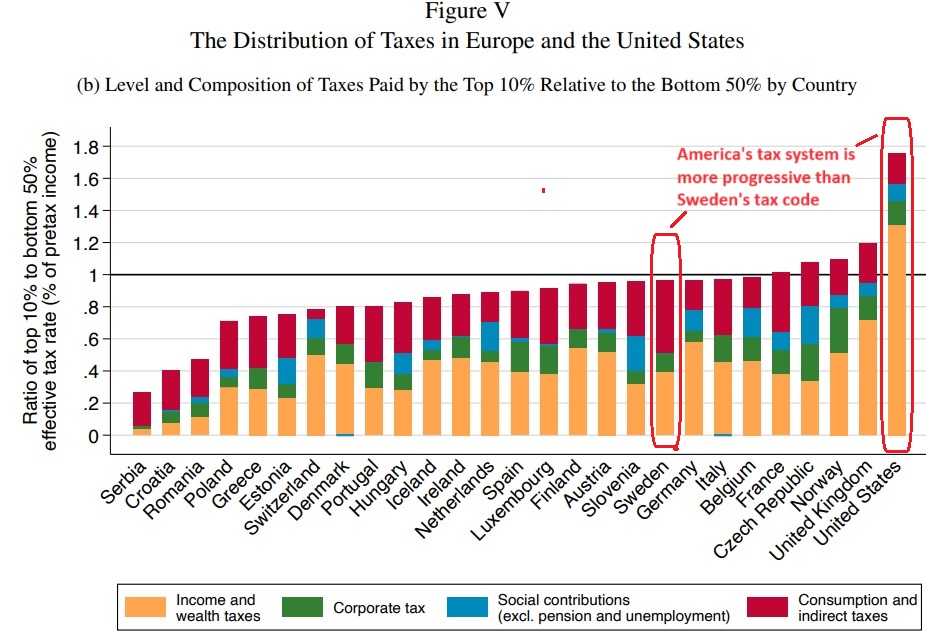

Here’s a chart from a study for the World Inequality Lab by three economists at the Paris School of Economics.

Here’s a chart from a study for the World Inequality Lab by three economists at the Paris School of Economics.

As you can see, the United States is an outlier. The rich pay a much bigger share of the tax burden in America compared to other nations.

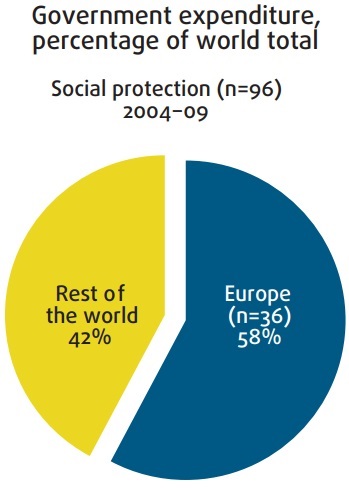

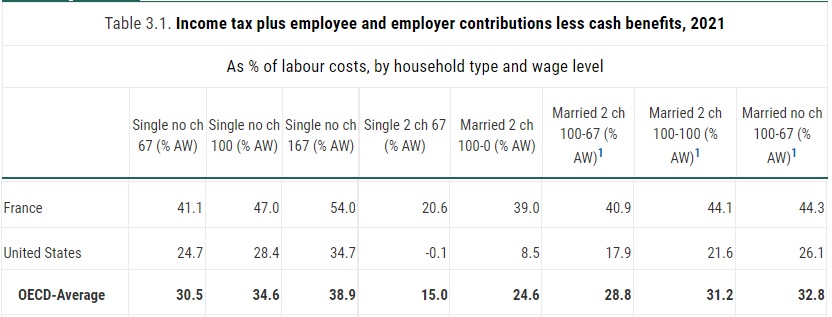

Interestingly, it’s not because America imposes higher taxes on the rich. It’s because Europeans impose higher taxes on lower-income and middle-class households.

Want more confirmation from another left-of-center source?

Here are some excerpts from a column in the New York Times by Monica Prasad, a sociology professor at Northwestern.

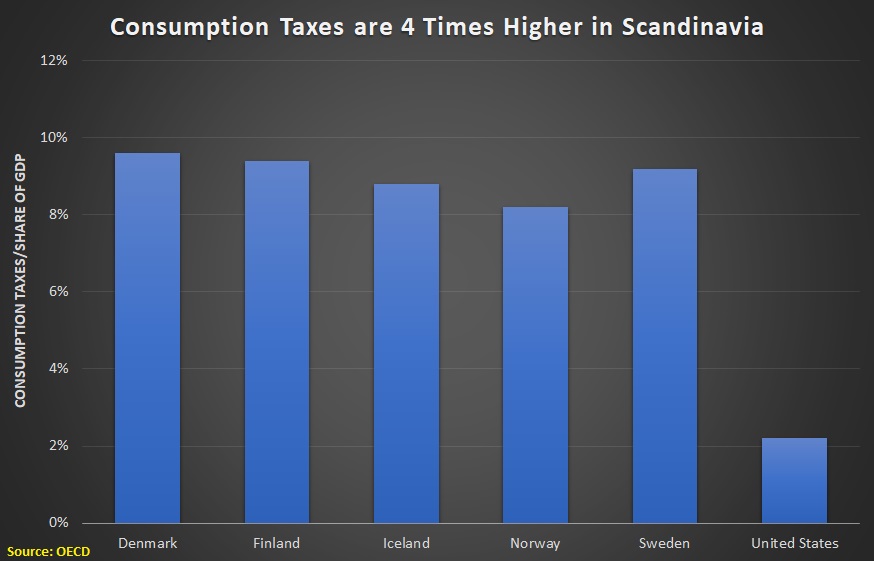

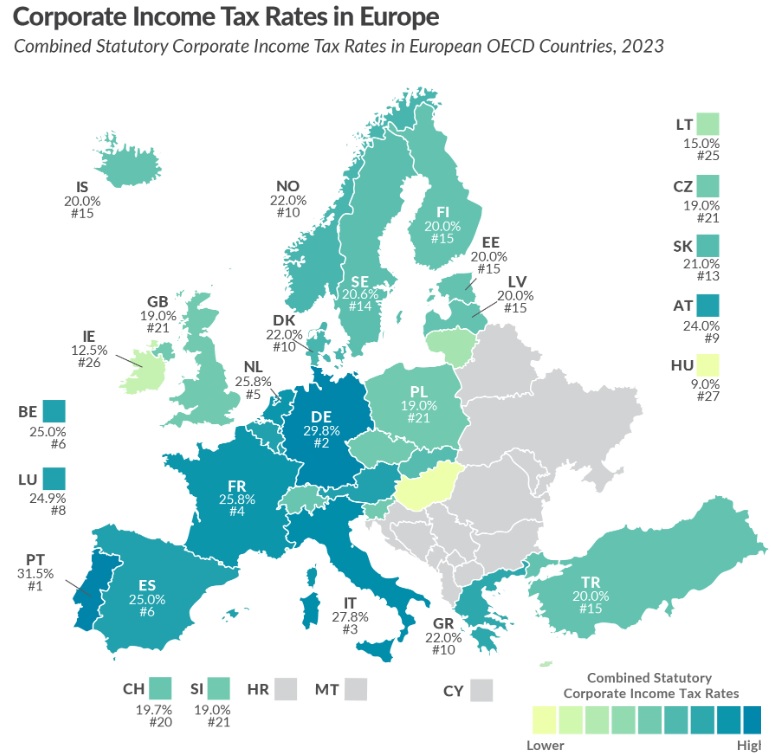

We can learn from Sweden, but the lesson is not what many people think. Rich Swedes do get taxed at high rates, but so does everyone else: The average American worker’s total tax burden is 31.7 percent of earnings, compared with 42.9 percent for the average Swede. The Swedes actually tax corporations less…

Estate tax? In the United States the average effective rate is 16.5 percent. In Sweden, it’s zero. Swedish national sales taxes, which fall disproportionately on the middle classes, are much higher than sales taxes in the United States. …Some scholars have drawn on this history to argue that the United States needs to give up its fixation with progressive taxation and adopt a national sales tax as every other advanced industrial country has done. …It’s hard to make a case for a big new tax in America on the middle classes and the poor…progressive taxation still has a role to play in the United States — but we do need to learn the larger lesson…the secret of the European welfare states.

Her view of the the “larger lesson” and “secret” is not the same as mine.

She wants an efficient welfare state and – to her credit – she acknowledges that means big tax burdens for lower-income and middle-class households.

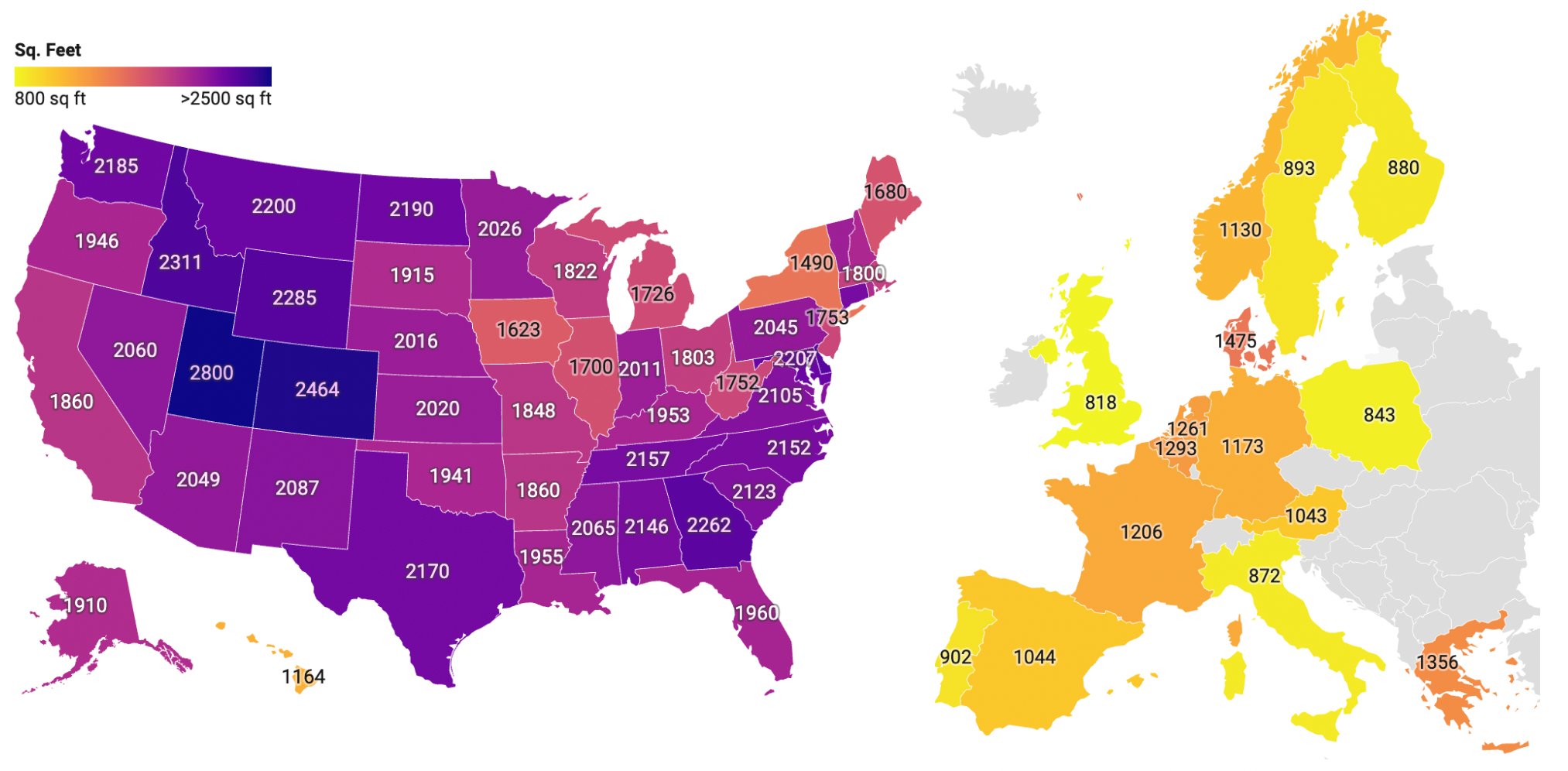

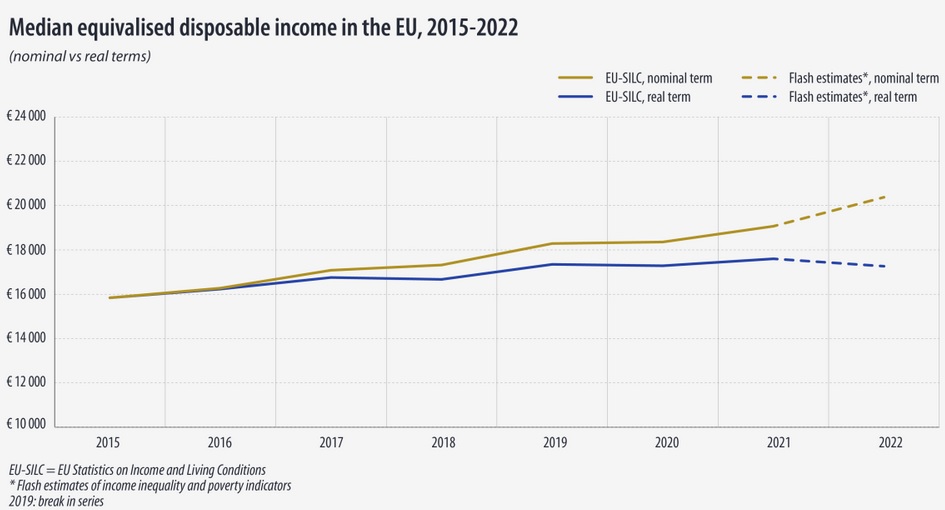

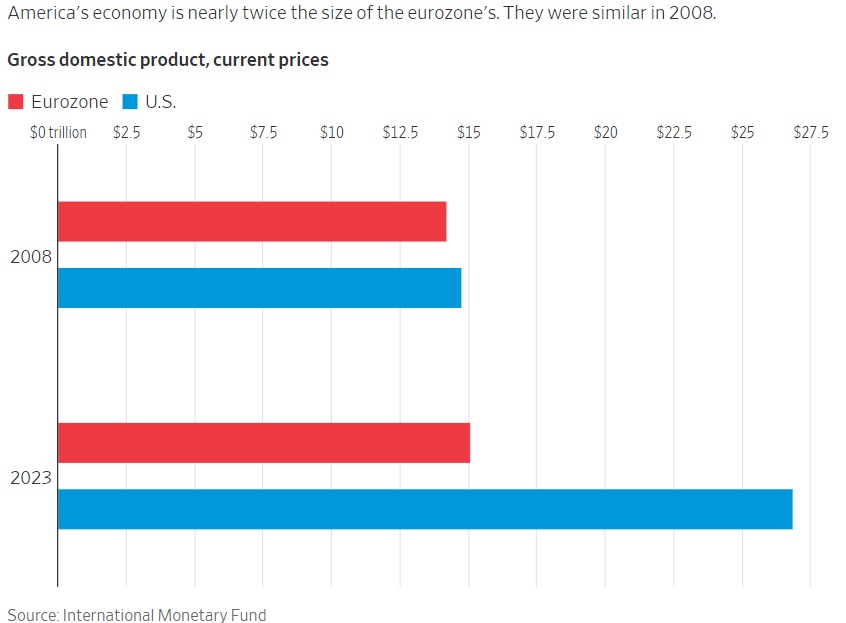

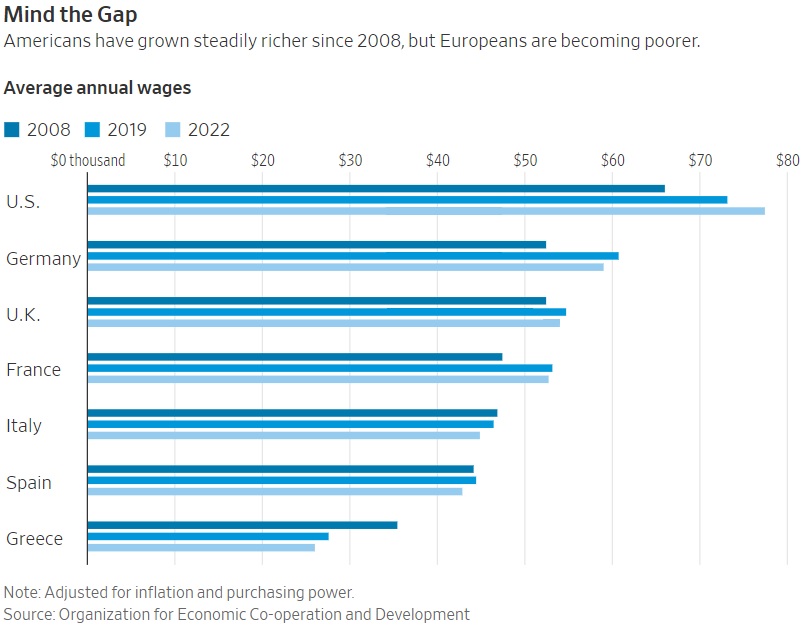

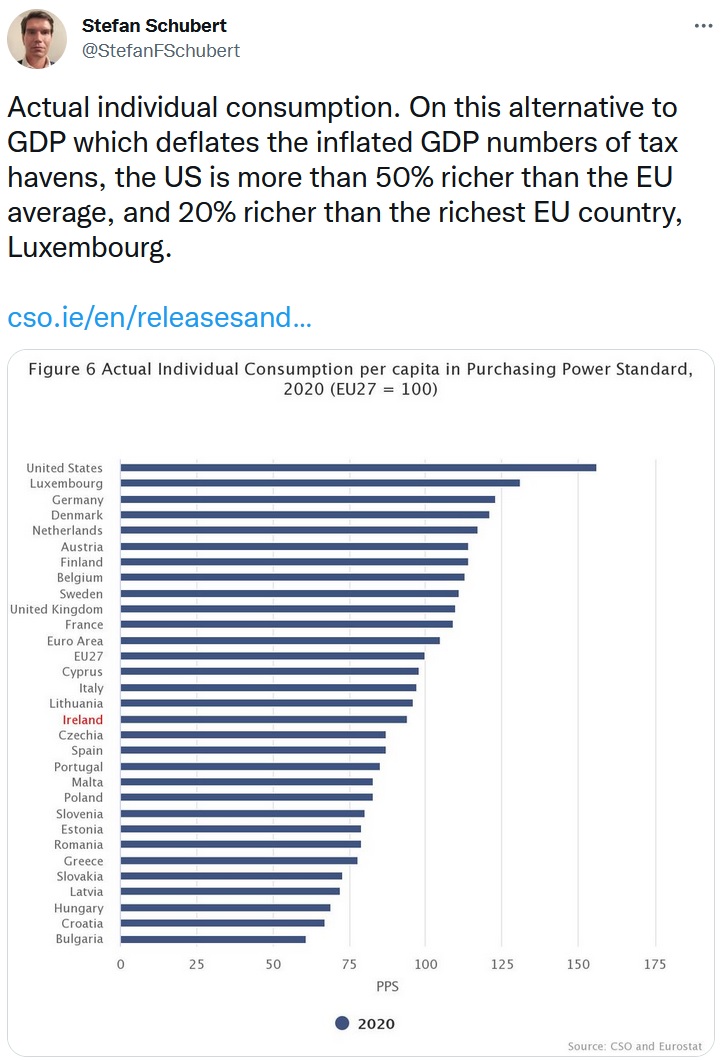

I look at comparative living standards and say “are you $&(#)@* crazy!”

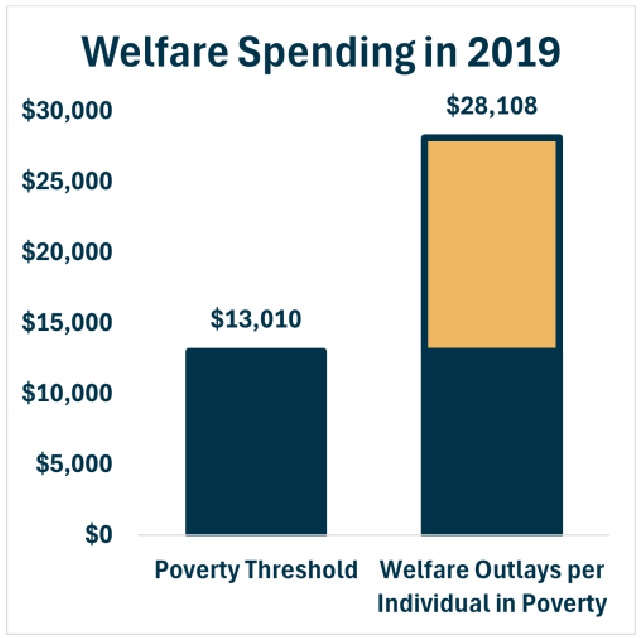

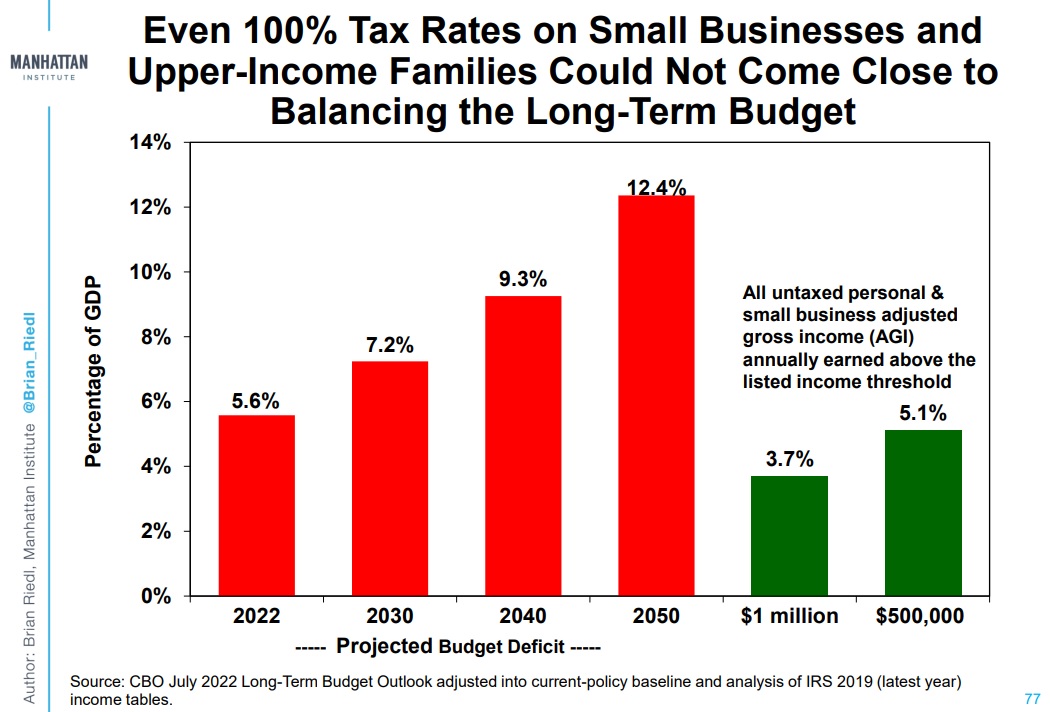

I’ll close by emphasizing a point I made at the end of the above video. Our friends on the left like to argue that big government is popular and they’ll cite polling data to make that case.

But people have much different answers to polling questions when they are asked if they are willing to pay higher taxes to finance bigger government.

And since there are not enough rich people to finance big government, the only way to have Swedish-sized government is to have Swedish-level taxes on ordinary people.

P.S. For those who want to focus solely on the taxation of rich households. Europeans tend to impose higher personal income tax rates but to also have less double taxation of income that is saved and invested.