I’ve previously written about the bizarre attack that the European Commission has launched against Ireland’s tax policy. The bureaucrats in Brussels have concocted a strange theory that Ireland’s pro-growth tax system provides “state aid” to companies like Apple (in other words, if you tax at a low rate, that’s somehow akin to giving handouts to a company,  at least if you start with the assumption that all income belongs to government).

at least if you start with the assumption that all income belongs to government).

This has produced two types of reactions. On the left, the knee-jerk instinct is that governments should grab more money from corporations, though they sometimes quibble over how to divvy up the spoils.

Senator Elizabeth Warren, for instance, predictably tells readers of the New York Times that Congress should squeeze more money out of the business community.

Now that they are feeling the sting from foreign tax crackdowns, giant corporations and their Washington lobbyists are pressing Congress to cut them a new sweetheart deal here at home. But instead of bailing out the tax dodgers under the guise of tax reform, Congress should seize this moment to…repair our broken corporate tax code. …Congress should increase the share of government revenue generated from taxes on big corporations — permanently. In the 1950s, corporations contributed about $3 out of every $10 in federal revenue. Today they contribute $1 out of every $10.

As part of her goal to triple the tax burden of companies, she also wants to adopt full and immediate worldwide taxation. What she apparently doesn’t understand (and there’s a lot she doesn’t understand) is that Washington may be capable of imposing bad laws on U.S.-domiciled companies, but it has rather limited power to impose bad rules on foreign-domiciled firms.

So the main long-run impact of a more onerous corporate tax system in America will be a big competitive advantage for companies from other nations.

The reaction from Jacob Lew, America’s Treasury Secretary, is similarly disappointing. He criticizes the European Commission, but for the wrong reasons. Here’s some of what he wrote for the Wall Street Journal, starting with some obvious complaints.

…the commission’s novel approach to its investigations seeks to impose unfair retroactive penalties, is contrary to well established legal principles, calls into question the tax rules of individual countries, and threatens to undermine the overall business climate in Europe.

But his solutions would make the system even worse. He starts by embracing the OECD’s BEPS initiative, which is largely designed to seize more money from US multinational firms.

…we have made considerable progress toward combating corporate tax avoidance by working with our international partners through what is known as the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, agreed to by the Group of 20 and the 35 member Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

He then regurgitates the President’s plan to replace deferral with worldwide taxation.

…the president’s plan directly addresses the problem of U.S. multinational corporations parking income overseas to avoid U.S. taxes. The plan would make this practice impossible by imposing a minimum tax on foreign income.

In other words, his “solution” to the European Commission’s money grab against Apple is to have the IRS grab the money instead. Needless to say, if you’re a gazelle,  you probably don’t care whether you’re in danger because of hyenas or jackals, and that’s how multinational companies presumably perceive this squabble between US tax collectors and European tax collectors.

you probably don’t care whether you’re in danger because of hyenas or jackals, and that’s how multinational companies presumably perceive this squabble between US tax collectors and European tax collectors.

On the other side of the issue, critics of the European Commission’s tax raid don’t seem overflowing with sympathy for Apple. Instead, they are primarily worried about the long-run implications.

Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center offers some wise insight on this topic, both with regards to the actions of the European Commission and also with regards to Treasury Secretary Lew’s backward thinking. Here’s what she wrote about the never-ending war against tax competition in Brussels.

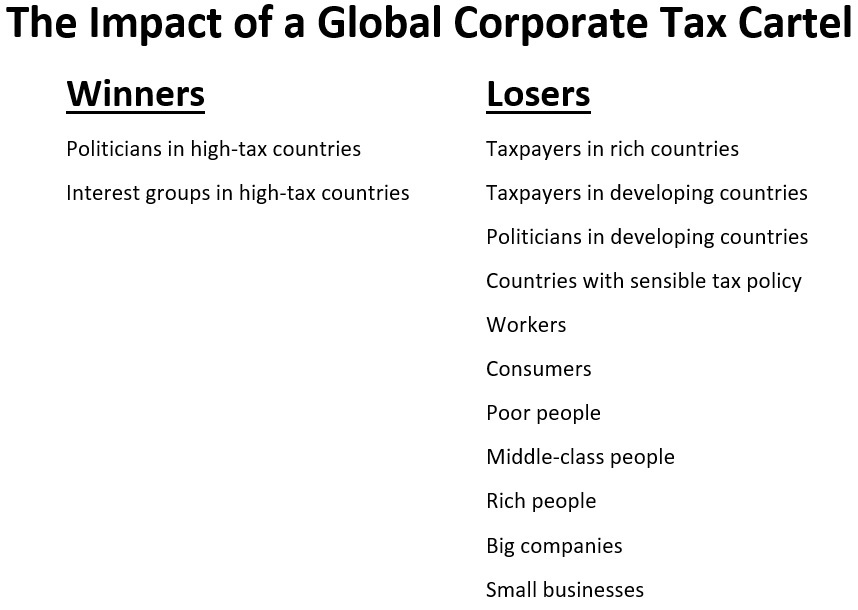

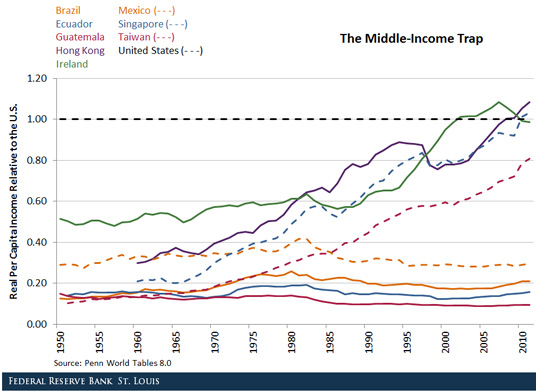

At the core of the retroactive penalty is the bizarre belief on the part of the European Commission that low taxes are subsidies. It stems from a leftist notion that the government has a claim on most of our income. It is also the next step in the EU’s fight against tax competition since, as we know, tax competition punishes countries with bad tax systems for the benefit of countries with good ones. The EU hates tax competition and instead wants to rig the system to give good grades to the high-tax nations of Europe and punish low-tax jurisdictions.

And she also points out that Treasury Secretary Lew (a oleaginous cronyist) is no friend of American business because of his embrace of worldwide taxation and BEPS.

…as Lew’s op-ed demonstrates, …they would rather be the ones grabbing that money through the U.S.’s punishing high-rate worldwide-corporate-income-tax system. …In other words, the more the EU grabs, the less is left for Uncle Sam to feed on. …And, as expected, Lew’s alternative solution for avoidance isn’t a large reduction of the corporate rate and a shift to a territorial tax system. His solution is a worldwide tax cartel… The OECD’s BEPS project is designed to increase corporate tax burdens and will clearly disadvantage U.S. companies. The underlying assumption behind BEPS is that governments aren’t seizing enough revenue from multinational companies. The OECD makes the case, as it did with individuals, that it is “illegitimate,” as opposed to illegal, for businesses to legally shift economic activity to jurisdictions that have favorable tax laws.

John O’Sullivan, writing for National Review, echoes Veronique’s point about tax competition and notes that elimination of competition between governments is the real goal of the European Commission.

…there is one form of European competition to which Ms. Vestager, like the entire Commission, is firmly opposed — and that is tax competition. Classifying lower taxes as a form of state aid is the first step in whittling down the rule that excludes taxation policy from the control of Brussels. It won’t be the last. Brussels wants to reduce (and eventually to eliminate) what it calls “harmful tax competition” (i.e., tax competition), which is currently the preserve of national governments. …Ms. Vestager’s move against Apple is thus a first step to extend control of tax policy by Brussels across Europe. Not only is this a threat to European taxpayers much poorer than Apple, but it also promises to decide the future of Europe in a perverse way. Is Europe to be a cartel of governments? Or a market of governments? A cartel is a group of economic actors who get together to agree on a common price for their services — almost always a higher price than the market would set. The price of government is the mix of tax and regulation; both extract resources from taxpayers to finance the purposes of government. Brussels has already established control of regulations Europe-wide via regulatory “harmonization.” It would now like to do the same for taxes. That would make the EU a fully-fledged cartel of governments. Its price would rise without limit.

Holman Jenkins of the Wall Street Journal offers some sound analysis, starting with his look at the real motives of various leftists.

…attacking Apple is a politically handy way of disguising a challenge to the tax policies of an EU member state, namely Ireland. …Sen. Chuck Schumer calls the EU tax ruling a “cheap money grab,” and he’s an expert in such matters. The sight of Treasury Secretary Jack Lew leaping to the defense of an American company when in the grips of a bureaucratic shakedown, you will have no trouble guessing, is explained by the fact that it’s another government doing the shaking down.

And he adds his warning about this fight really being about tax competition versus tax harmonization.

Tax harmonization is a final refuge of those committed to defending Europe’s stagnant social model. Even Ms. Vestager’s antitrust agency is jumping in, though the goal here oddly is to eliminate competition among jurisdictions in tax policy, so governments everywhere can impose inefficient, costly tax regimes without the check and balance that comes from businesses being able to pick up and move to another jurisdiction. In a harmonized world, of course, a check would remain in the form of jobs not created, incomes not generated, investment not made. But Europe has been wiling to live with the harmony of permanent recession.

Even the Economist, which usually reflects establishment thinking, argues that the European Commission has gone overboard.

…in tilting at Apple the commission is creating uncertainty among businesses, undermining the sovereignty of Europe’s member states and breaking ranks with America, home to the tech giant… Curbing tax gymnastics is a laudable aim. But the commission is setting about it in the most counterproductive way possible. It says Apple’s arrangements with Ireland, which resulted in low-single-digit tax rates, amounted to preferential treatment, thereby violating the EU’s state-aid rules. Making this case involved some creative thinking. The commission relied on an expansive interpretation of the “transfer-pricing” principle that governs the price at which a multinational’s units trade with each other. Having shifted the goalposts in this way, the commission then applied its new thinking to deals first struck 25 years ago.

Seeking a silver lining to this dark cloud, the Economist speculates whether the EC tax raid might force American politicians to fix the huge warts in the corporate tax system.

Some see a bright side. …the realisation that European politicians might gain at their expense could, optimists say, at last spur American policymakers to reform their barmy tax code. American companies are driven to tax trickery by the combination of a high statutory tax rate (35%), a worldwide system of taxation, and provisions that allow firms to defer paying tax until profits are repatriated (resulting in more than $2 trillion of corporate cash being stashed abroad). Cutting the rate, taxing only profits made in America and ending deferral would encourage firms to bring money home—and greatly reduce the shenanigans that irk so many in Europe. Alas, it seems unlikely.

America desperately needs a sensible system for taxing corporate income, so I fully agree with this passage, other than the strange call for “ending deferral.” I’m not sure whether this is an editing mistake or a lack of understanding by the reporter, but deferral is no longer an issue if the tax code is reformed to that the IRS is “taxing only profits made in America.”

But the main takeaway, as noted by de Rugy, O’Sullivan, and Jenkins, is that politicians want to upend the rules of global commerce to undermine and restrict tax competition. They realize that the long-run fiscal outlook of their countries is grim, but rather than fix the bad policies they’ve imposed, they want a system that will enable higher ever-higher tax burdens.

In the long run, that leads to disaster, but politicians rarely think past the next election.

P.S. To close on an upbeat point, Senator Rand Paul defends Apple from predatory politicians in the United States.

Read Full Post »

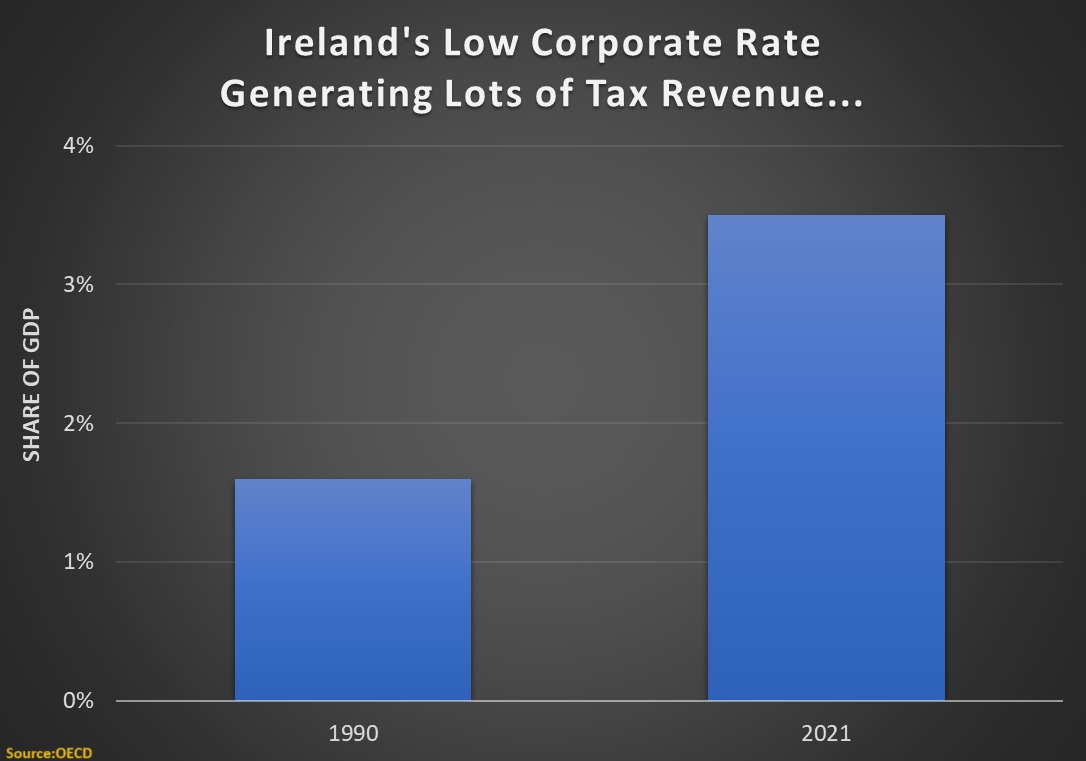

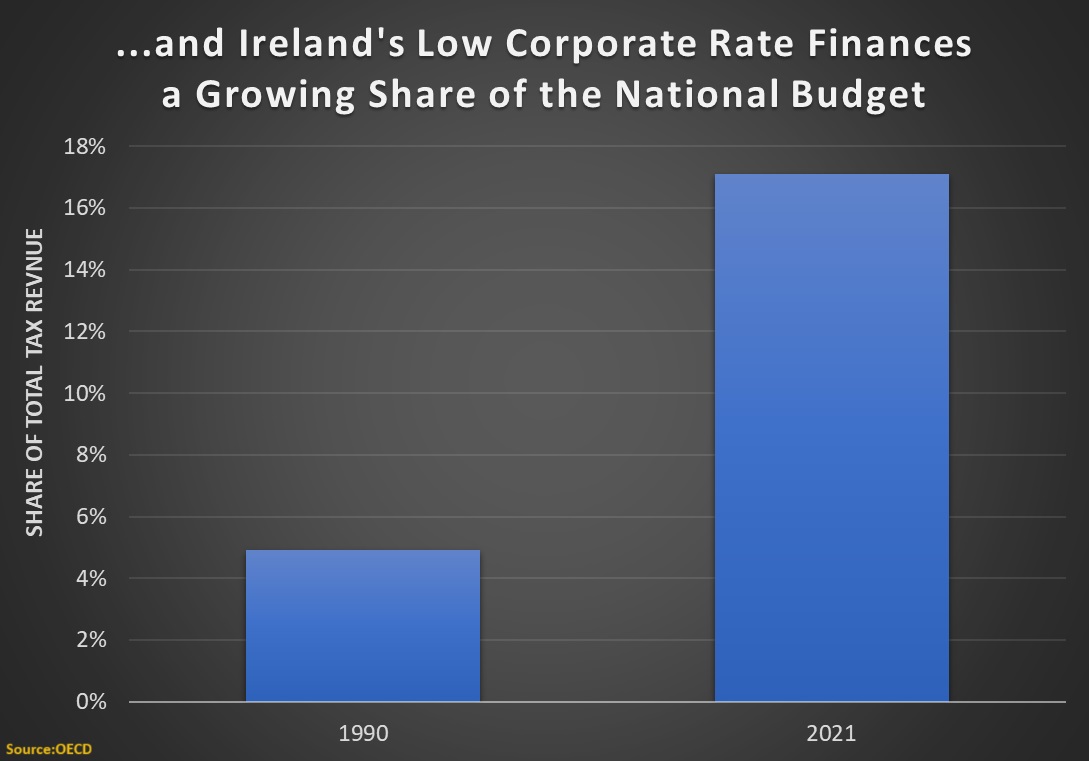

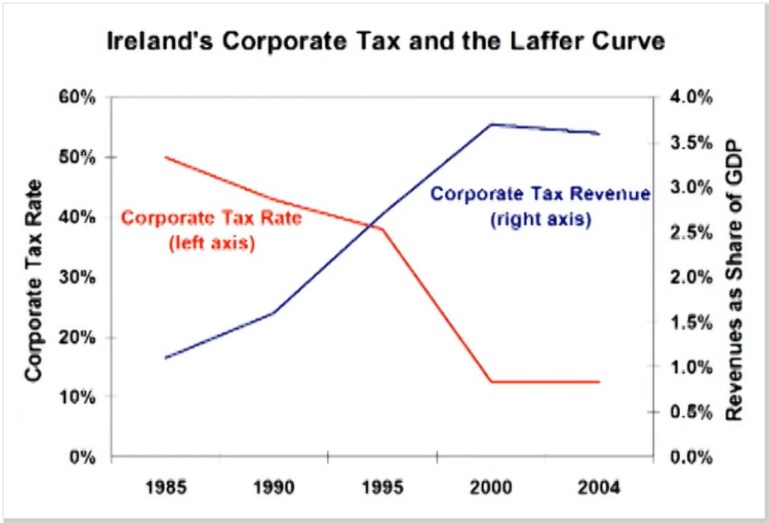

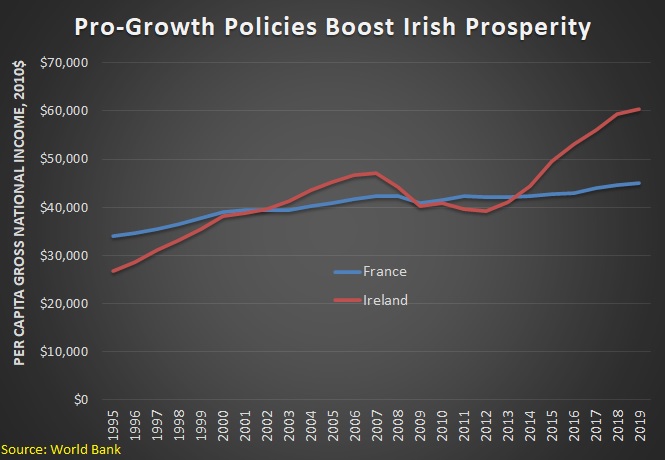

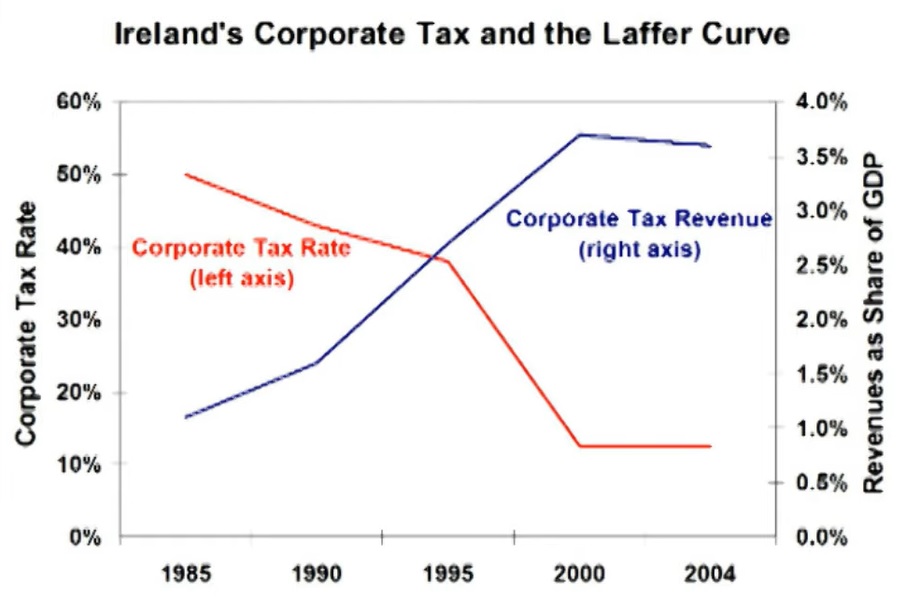

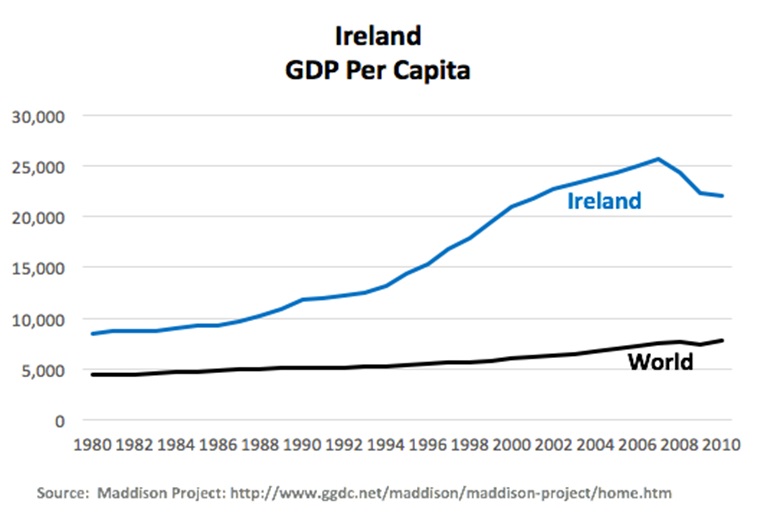

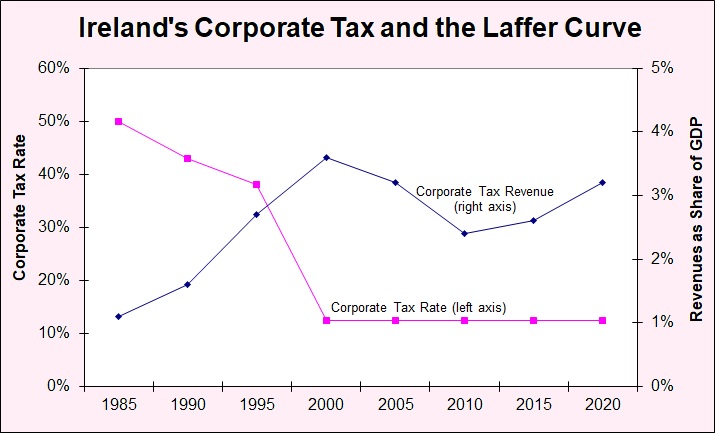

According to the New York Times, Ireland was collecting so much corporate tax revenue that the government was having a hard time figuring out what to do with all the money (as you might expect, I suggested that politicians lower other taxes).

According to the New York Times, Ireland was collecting so much corporate tax revenue that the government was having a hard time figuring out what to do with all the money (as you might expect, I suggested that politicians lower other taxes).…French economist Thomas Picketty, professor at France’s school for advanced studies in social studies (EHESS)…, said Ireland is “siphoning” taxes off other countries. …Their comments follow a tweet on Wednesday by French economist Gabriel Zucman, head of the EU Tax Observatory and author of a recent EU-funded report that called Ireland a tax haven. …It comes the same week corporation tax receipts were revealed to be up more than a quarter in November compared with the same month last year, boosting overall revenues and putting the State on track to beat last year’s record tax take.

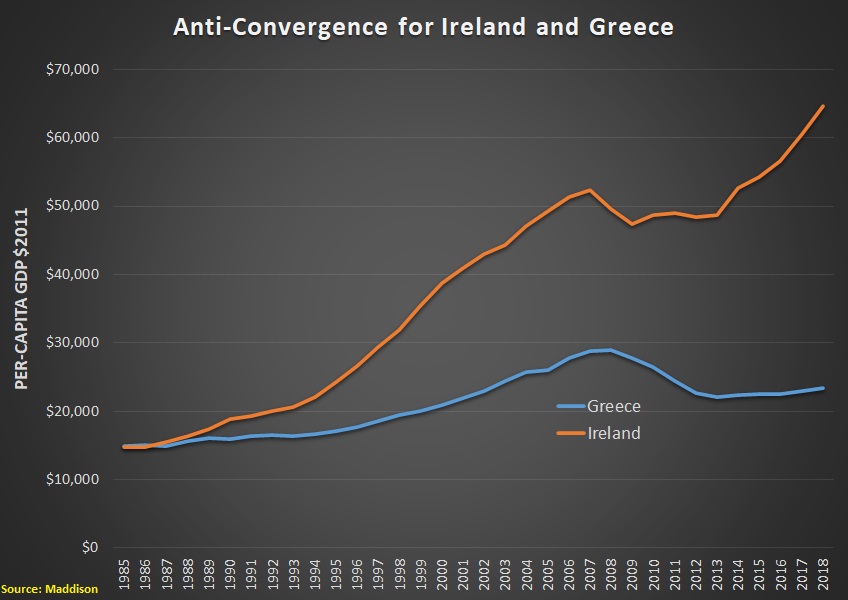

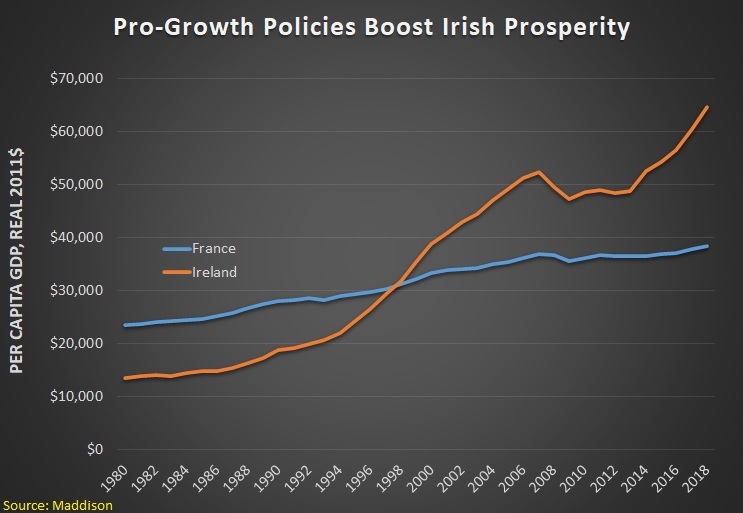

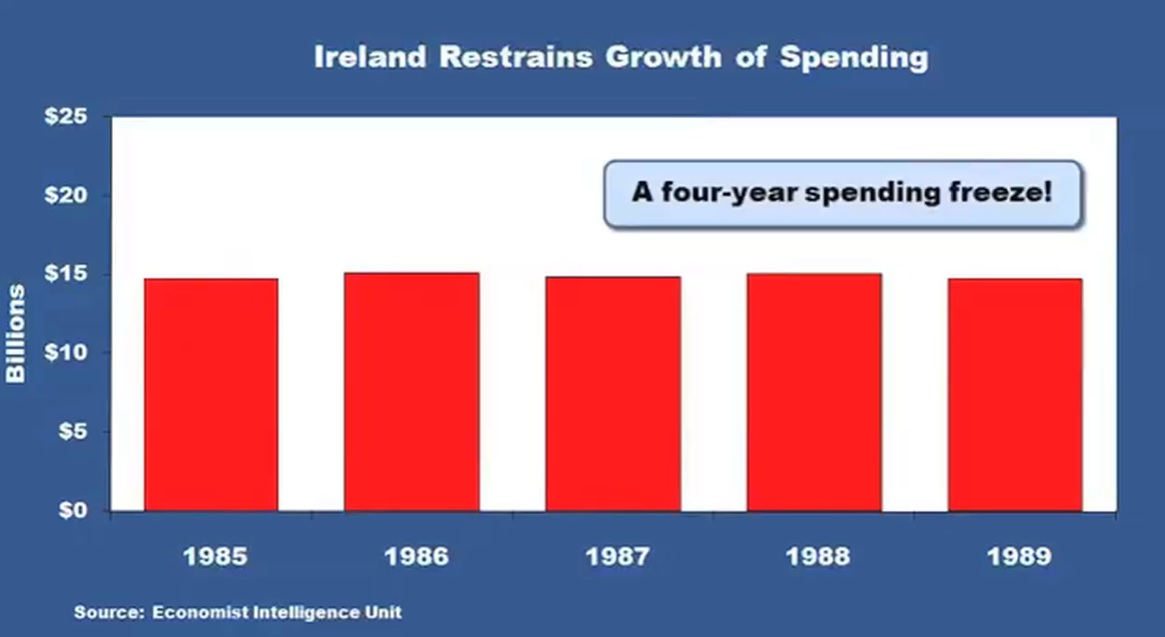

…In 2022, the Irish economy grew at the astonishing rate of 12.2 percent, the fastest on the European continent. (By comparison, the US economy grew by 2.1 percent in 2022.) If you think there’s no connection between Irish freedom and Irish prosperity, contact your economics teachers and demand a refund. …Ireland ranks high because property rights and contracts are well protected. The business climate is friendly because regulations aren’t nutty and intrusive, while tax rates are competitive. …It’s freedom, not the “luck of the Irish,” that explains Ireland’s remarkable economic success.