There aren’t many fiscal policy role models in Europe.

Switzerland surely is at the top of the list. The burden of government spending is modest by European standards, in part because of a very good spending cap that prevents politicians from overspending when revenues are buoyant. Tax rates also are reasonable. The central government’s tax system is “progressive,” but the top rate is only 11.5 percent. And tax competition among the cantons ensures that sub-national tax rates don’t get too high. Because of these good policies, Switzerland completely avoided the fiscal crisis plaguing the rest of the continent.

Switzerland surely is at the top of the list. The burden of government spending is modest by European standards, in part because of a very good spending cap that prevents politicians from overspending when revenues are buoyant. Tax rates also are reasonable. The central government’s tax system is “progressive,” but the top rate is only 11.5 percent. And tax competition among the cantons ensures that sub-national tax rates don’t get too high. Because of these good policies, Switzerland completely avoided the fiscal crisis plaguing the rest of the continent.

The Baltic nations of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia also deserve some credit. They allowed spending to rise far too rapidly in the middle of last decade – an average of nearly 17 percent per year between 2002 and 2008! But they have since moved in the right direction, with genuine spending cuts (unlikely the fake cuts that characterize fiscal policy in nations like the United States and United Kingdom). Yes, the Baltic countries did raise some taxes, which undermined the positive effects of spending reductions, but at least they focused primarily on spending and preserved their attractive flat tax systems. No wonder growth has rebounded in these nations.

The Baltic nations of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia also deserve some credit. They allowed spending to rise far too rapidly in the middle of last decade – an average of nearly 17 percent per year between 2002 and 2008! But they have since moved in the right direction, with genuine spending cuts (unlikely the fake cuts that characterize fiscal policy in nations like the United States and United Kingdom). Yes, the Baltic countries did raise some taxes, which undermined the positive effects of spending reductions, but at least they focused primarily on spending and preserved their attractive flat tax systems. No wonder growth has rebounded in these nations.

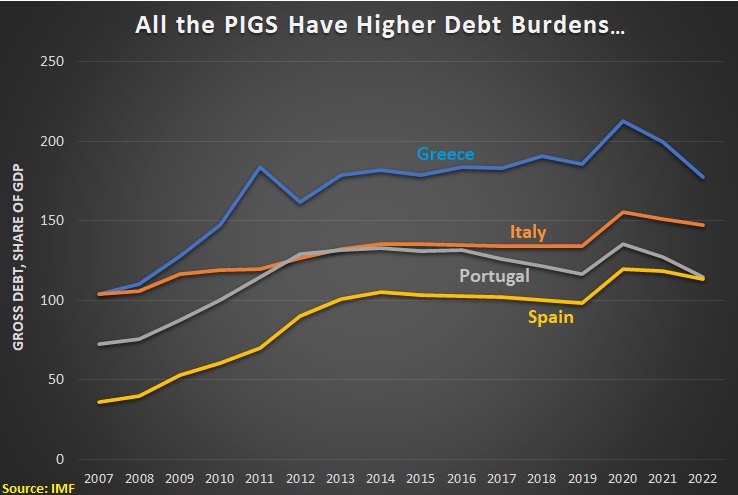

The situation in the rest of Europe is more bleak, particularly for the so-called PIIGS. To varying degrees, Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain have lost the ability to borrow, received bailouts, and been mired in recession.

The silver lining is that the fiscal crisis has forced them to finally cut spending. All of those nations implemented real spending cuts in 2011 according to European Commission data, bringing spending below 2010 levels. Final figures for 2012 aren’t available, of course, but the International Monetary Fund estimates that spending will drop in every nation other than Italy (where it will climb by less than 1 percent).

That’s the good news. The public sector finally is being subjected to some long-overdue fiscal discipline.

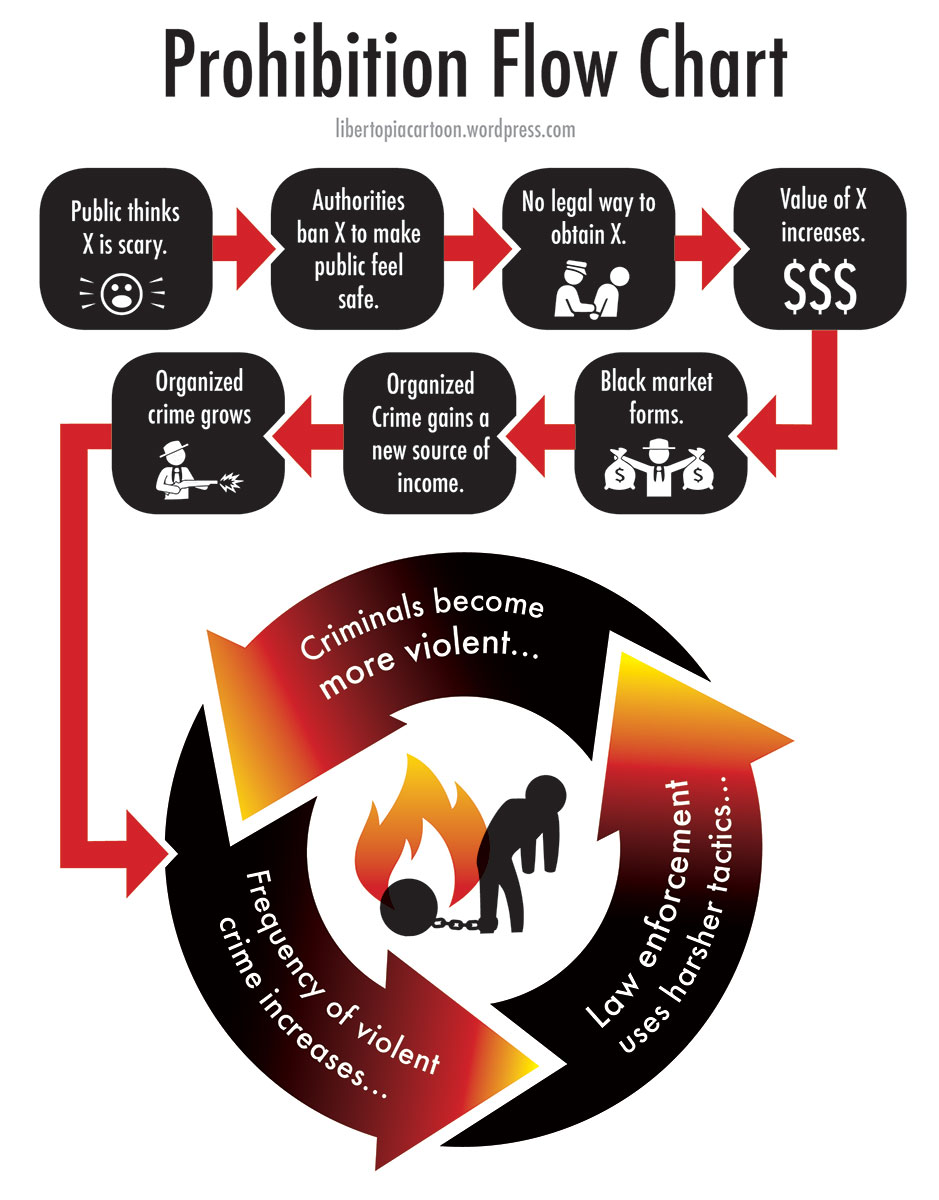

The bad news is that politicians also imposed very significant tax increases on the private sector. Income tax rates have been increased. Value-added taxes have been hiked, and other taxes have climbed as well. These penalties on productive activity undermine potential growth.

The politicians say that this is a “balanced approach,” but this view is misguided, First, as Veronique de Rugy has shown, it generally means lots of new taxes and very little spending restraint. Second, it is based on the IMF view of “austerity,” which mistakenly focuses on the symptom of red ink rather than the underlying disease of too much spending.

What Europe really needs is a combination of lower spending and lower tax rates.

Portugal may actually be moving in that direction, according to a report in the Wall Street Journal.

The Portuguese government is seeking to cut its corporate tax rate for new businesses to one of the lowest in Europe as part of a plan to attract investment and revitalize ailing industries, the minister of economy said. The government is in talks with the European Commission’s competition agency in Brussels to get approval to cut the tax on corporate income for new investors to 10% from the current 25%, the minister, Alvaro Santos Pereira, said in an interview. …”We want to make Portugal one of the most attractive countries in Europe for new investment,” Mr. Santos Pereira said. “We believe that by providing very strong fiscal incentives to new investments we will safeguard the budget side and at the same time become a lot more competitive,” he added. …While wealthy euro-zone countries and the IMF are beginning to recognize the need for measures to boost growth in austerity-hit countries, they have been reluctant to endorse tax cuts in countries under bailout programs. If implemented, the proposed tax cut would be a departure from a series of tax increases that countries including Portugal, Greece and Spain were forced to take as part their bailout conditions.

Before getting too excited, it’s important to note that the Portuguese proposal is a bit gimmicky.-1.gif) It’s not a corporate tax rate of 10 percent, it’s a special rate of 10 percent for new investment, however that’s defined.

It’s not a corporate tax rate of 10 percent, it’s a special rate of 10 percent for new investment, however that’s defined.

But at least it might be a small step in the right direction. As the article indicates, it “would be a departure from a series of tax increases.” And Portugal definitely has been guilty in recent years of raping and pillaging the private sector.

To be fair, though, this chart shows that government spending in Portugal did decline last year. And the IMF is projecting that it will fall again this year and next year.

But the key to good fiscal policy is reducing government spending as a share of economic output. And if tax increases keep the private economy in the dumps, then the actual burden of government spending doesn’t change much even when nominal outlays decline.

A pro-growth policy is needed to boost economic performance. Portugal’s corporate tax rate proposal, by itself, won’t make much of a difference. But if it’s the start of a trend, that could be significant.

By the way, it’s amusing to see that one of the bureaucrats from the European Commission is pouring cold water on the plan, implying that a decision to take less money from a company somehow is akin to government assistance.

“We would want to be sure that anything proposed would help the competitiveness of the economy,” said spokesman Simon O’Connor, “but at the same time it would have to be in line with state aid rules,” referring to EU regulations that limit the assistance governments can give to the private sector. “There really isn’t any scope for them to reduce revenue,” he added.

But I guess that’s not too surprising. Along with their tax-free colleagues at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the European Commission has been trying to undermine tax competition and make it easier for nations to impose bad tax policy.

Returning to our main topic, what’s next for Portugal?

Your guess is as good as mine, but Portugal’s leaders already have acknowledged that Keynesian fiscal policy is ineffective. Perhaps they’ve gotten to the point where they realize punitive tax systems also are destructive.

Read Full Post »

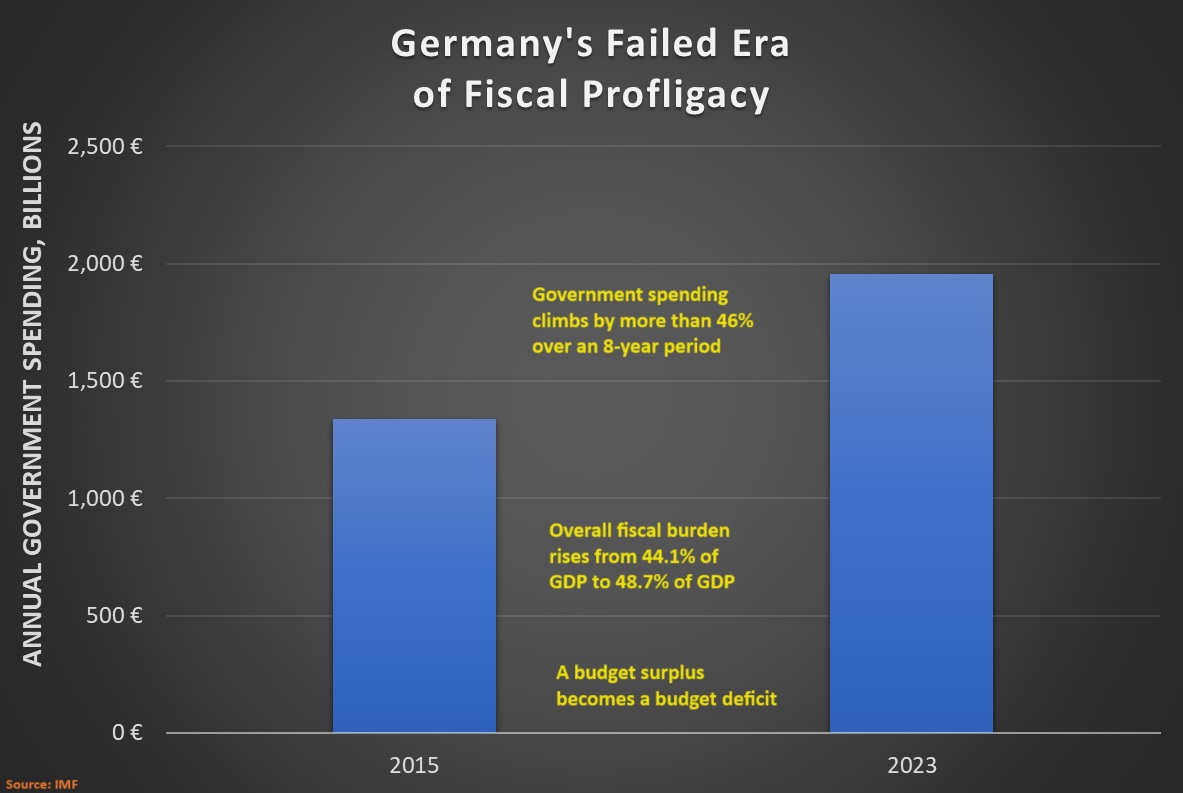

Over the past eight years, government spending has grown much faster than the private sector, thus violating the Golden Rule of fiscal policy.

Over the past eight years, government spending has grown much faster than the private sector, thus violating the Golden Rule of fiscal policy.In a reversal of fortunes, the laggards have become leaders. Greece, Spain and Portugal grew in 2023 more than twice as fast as the eurozone average. Italy was not far behind. …southern European countries made crucial changes that have attracted investors, revived growth and…reversed record-high unemployment. Governments cut red tape and corporate taxes to stimulate business and pushed through changes to their once-rigid labor markets, including making it easier for employers to hire and fire workers.

-1.gif)