I’m still in China, as part of a week-long teaching assignment about markets, entrepreneurship, economics, and fiscal policy at Northeastern University in Shenyang.

One point that I’ve tried to get across to the students is that China should not copy the United States. Or France, Japan, or Sweden.  To be more specific, I warn them that China won’t become rich if it copies the economic policies that those nations have today.

To be more specific, I warn them that China won’t become rich if it copies the economic policies that those nations have today.

Instead, I tell them that China should copy the economic policies – very small government, trivial or nonexistent income taxes, very modest regulation – that existed in those nations back in the 1800s and early 1900s. That’s when America and other western countries made the transition from agricultural poverty to industrial prosperity.

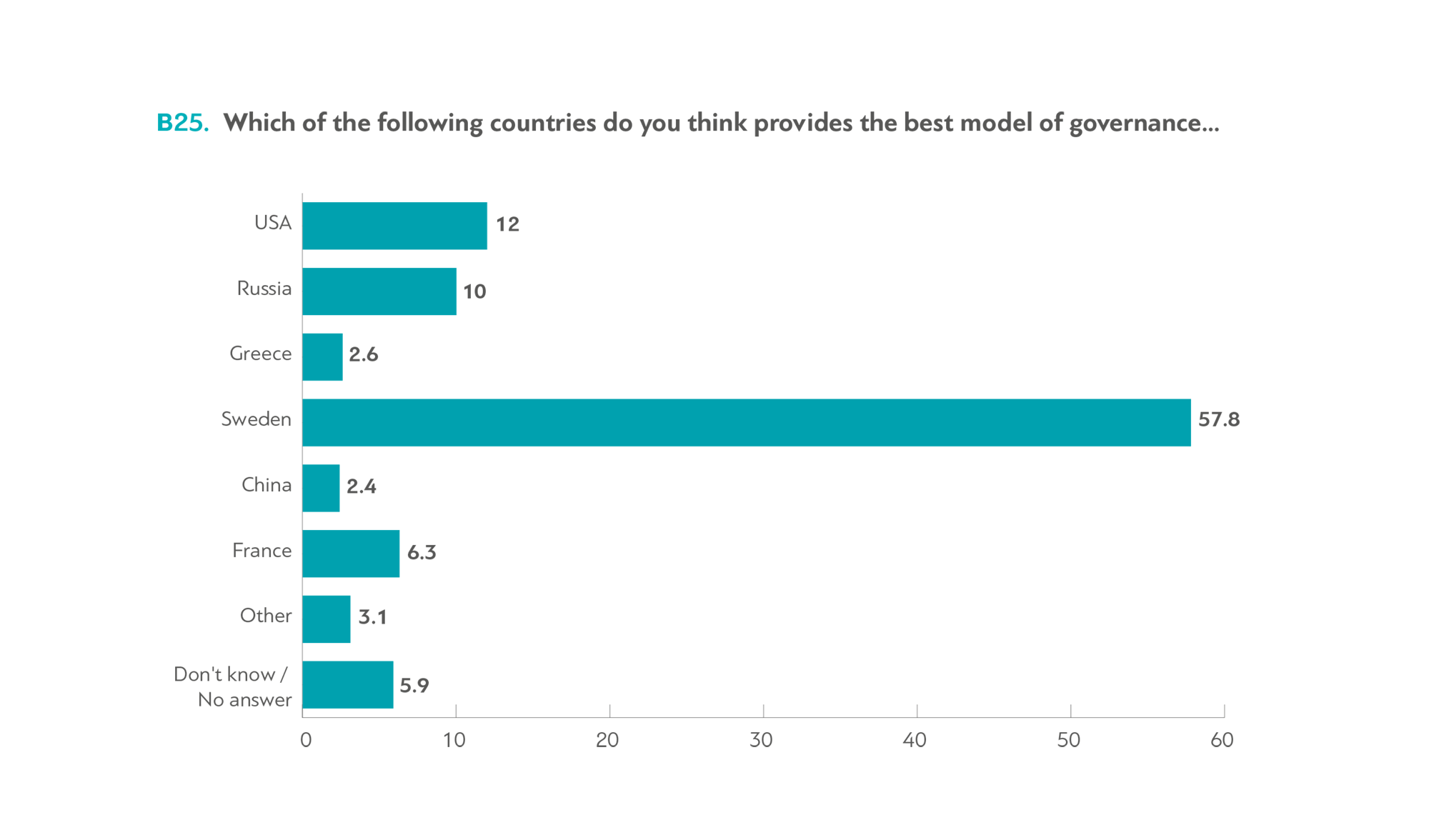

In other words, pay attention to the polices that actually produced prosperity, not the policies that happen to be in place in 2016. With this in mind, I’m delighted to share a new National Review column about the ostensibly wonderful Nordic Model from Nima Sanandaji. He starts by noting that statists are big fans of nations such as Sweden and Denmark.

Ezra Klein, the editor of the liberal news website Vox, wrote last fall that “Clinton and Sanders both want to make America look a lot more like Denmark — they both want to…strengthen the social safety net.” … Bill Clinton argues that Finland, Sweden, and Norway offer greater opportunities for individuals… Barack Obama recently…explain[ed] that “in a world of growing economic disparities, Nordic countries have some of the least income inequality in the world.”

Sounds nice, but there’s one itsy-bitsy problem with the left’s hypothesis.

Simply stated, everything good about Nordic nations was already in place before the era of big government.

…the social success of Nordic countries pre-dates progressive welfare-state policies. …their economic and social success had already materialized during a period when these countries combined a small public sector with free-market policies. The welfare state was introduced afterward.

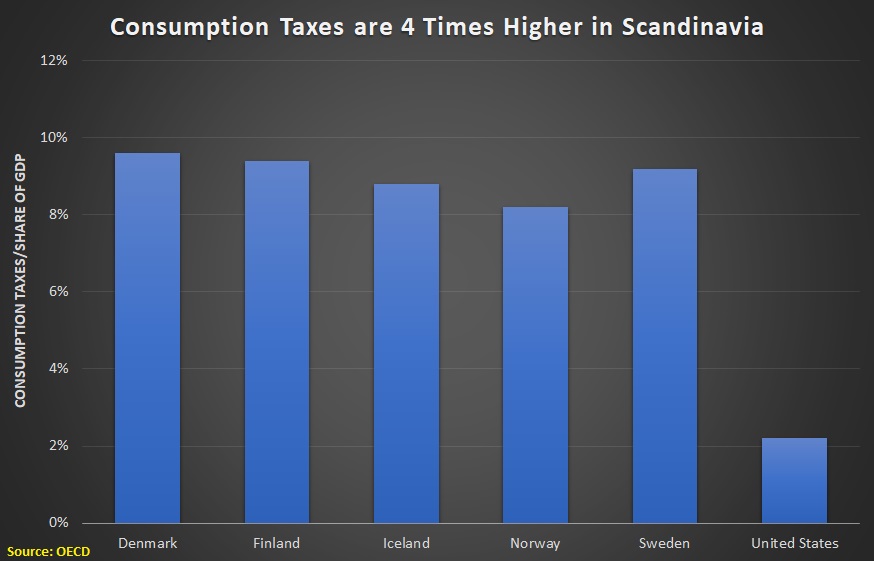

Here are some of the key factoids about fiscal policy.

…in 1960, the tax rate in [Denmark] was merely 25 percent of GDP, lower than the 27 percent rate in the U.S. at the time. In Sweden, the rate was 29 percent, only slightly higher than in the U.S. In fact, much of Nordic prosperity evolved between the time that a capitalist model was introduced in this part of the world during the late 19th century and the mid 20th century – during the free-market era.

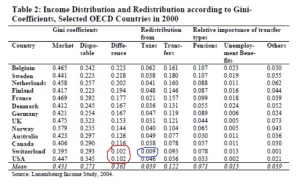

And here’s the data about equality (though I think it’s far more important to worry about the degree of upward mobility rather than whether everyone has a similar amount of income).

…high levels of income equality evolved during the same period. Swedish economists Jesper Roine and Daniel Waldenström, for example, explain that “most of the decrease [in income inequality in Sweden] takes place before the expansion of the welfare state and by 1950 Swedish top income shares were already lower than in other countries.” A recent paper by economists Anthony Barnes Atkinson and Jakob Egholt Søgaard reaches a similar conclusion for Denmark and Norway.

Our friends on the left think that government-run healthcare deserves the credit for longer lifespans in the Nordic world.

Nima explains that the evidence points in the other direction.

In 1960, well before large welfare states had been created in Nordic countries, Swedes lived 3.2 years longer than Americans, while Norwegians lived 3.8 years longer and Danes 2.4 years longer. Today, after the Nordic countries have introduced universal health care, the difference has shrunk to 2.9 years in Sweden, 2.6 years in Norway, and 1.5 years in Denmark. The differences in life span have actually shrunk as Nordic countries moved from a small public sector to a democratic-socialist model with universal health coverage.

Not to mention that there are some surreal horror stories in those nations about the consequences of putting government in charge of health care.

Here’s the evidence that I find most persuasive (some of which I already shared because of an excellent article Nima wrote for Cayman Financial Review).

Here’s the evidence that I find most persuasive (some of which I already shared because of an excellent article Nima wrote for Cayman Financial Review).

Danish Americans today have fully 55 percent higher living standard than Danes. Similarly, Swedish Americans have a 53 percent higher living standard than Swedes. The gap is even greater, 59 percent, between Finnish Americans and Finns. Even though Norwegian Americans lack the oil wealth of Norway, they have a 3 percent higher living standard than their cousins overseas. …Nordic Americans are more socially successful than their cousins in Scandinavia. They have much lower high-school-dropout rates, much lower unemployment rates, and even slightly lower poverty rates.

Nima concludes his article by noting the great irony of Nordic nations trying to reduce their welfare states at the same time American leftists are trying to move in the other direction.

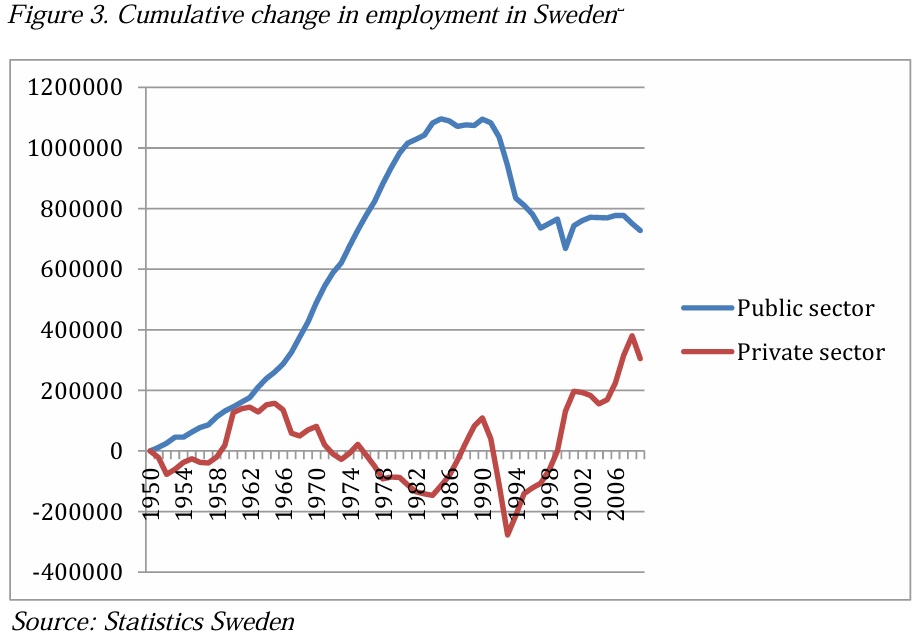

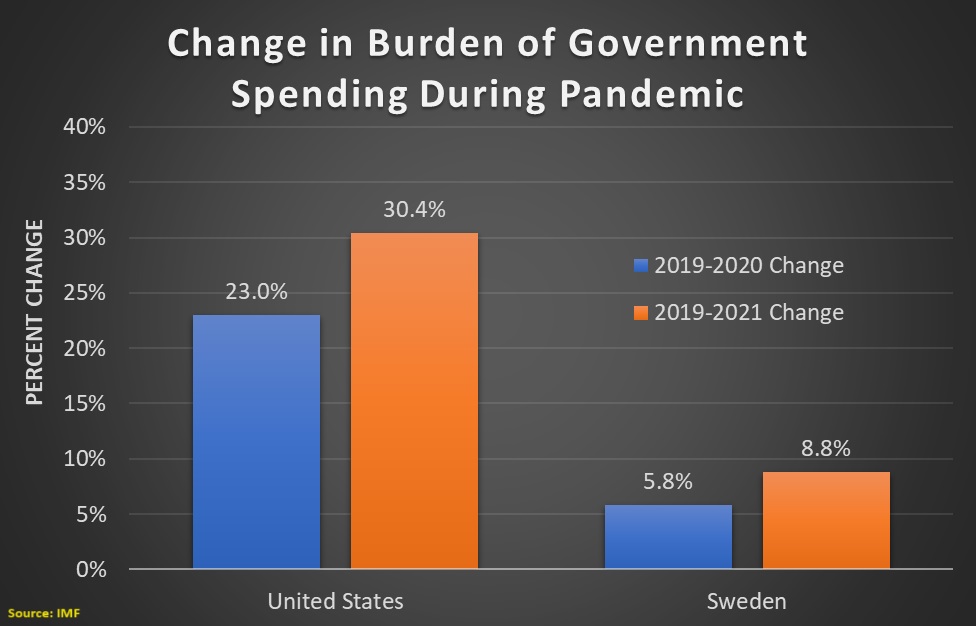

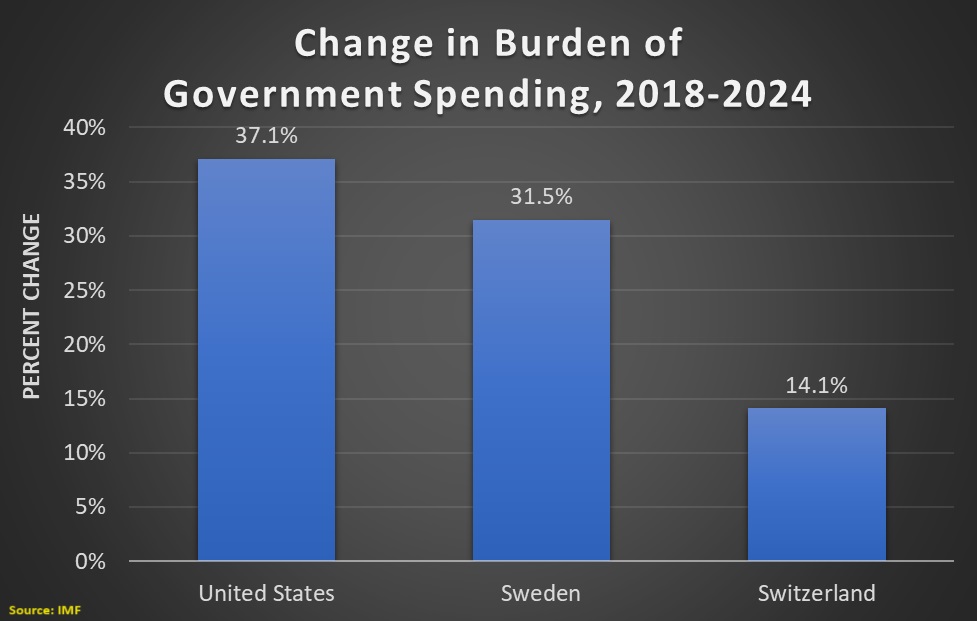

Nordic-style democratic socialism is all the rage among Democrat activists as well as with liberal intellectuals and journalists. But in the Nordic countries themselves, this ideal has gradually lost its appeal. …During the past few decades, the Nordic countries have gradually been reforming their social systems. Taxes have been cut to stimulate work, public benefits have been limited in order to reduce welfare dependency, pension savings have been partially privatized, for-profit forces have been allowed in the welfare sector, and state monopolies have been opened up to the market. In short, the universal-welfare-state model is being liberalized. Even the social-democratic parties themselves realize the need for change.

The net result of these reforms is that the Nordic nations are a strange combination of many policies that are very good  (very little regulation, very strong property rights, very open trade, and stable money) and a couple of policies that are very bad (an onerous tax burden and a bloated welfare state).

(very little regulation, very strong property rights, very open trade, and stable money) and a couple of policies that are very bad (an onerous tax burden and a bloated welfare state).

I’ve previously shared (many times) observations about the good features of the Nordic nations, so let’s take a closer look at the bad fiscal policies.

Sven Larson authored a study about the Swedish tax system for the Center for Freedom and Prosperity. The study is about 10 years old, but it remains the best explanation I’ve seen if you want to understand the ins and outs of taxation in Sweden.

Here’s some of what he wrote, starting with the observation that the fiscal burden used to be considerably smaller than it is in America today.

Sweden was not always a high-tax nation. …the aggregate tax burden after World War II was modest.

But then things began to deteriorate.

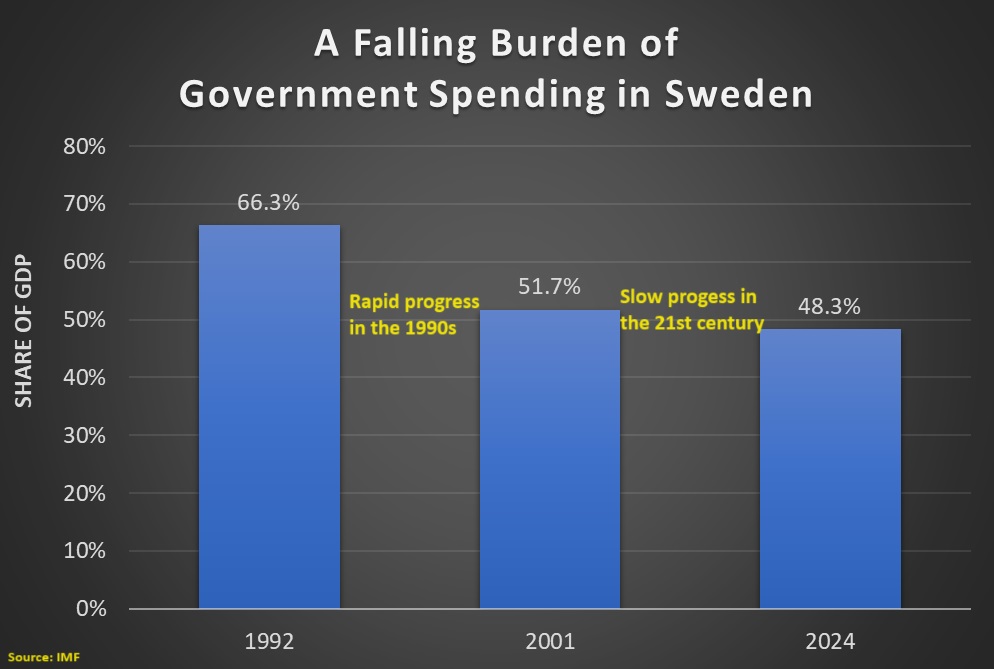

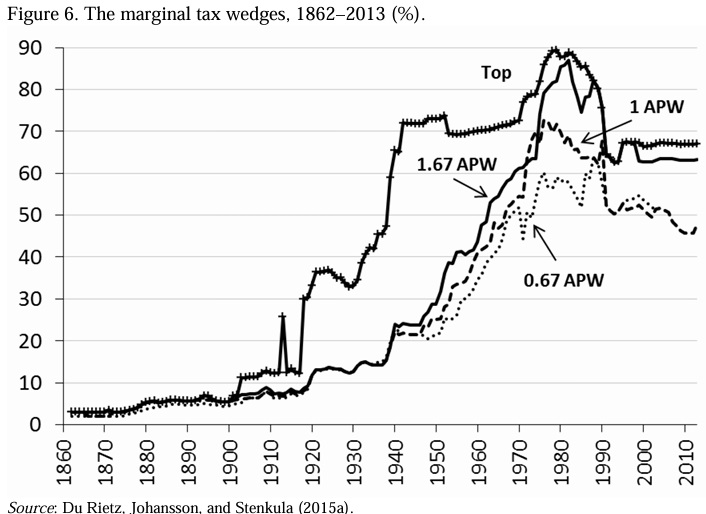

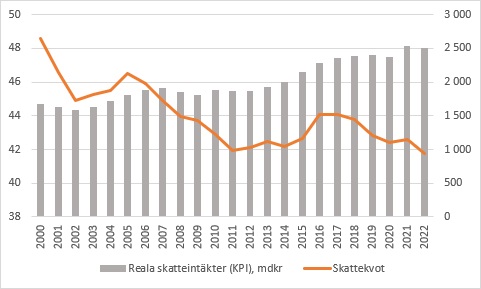

…over the next four decades, there was a relentless increase in taxation. The tax burden first reached 50 percent of economic output in 1986 and has generally stayed above that level for the past 20 years.

Though Sven points out that Swedish politicians, if nothing else, at least figured out that it’s not a good idea to be on the wrong side of the Laffer Curve (i.e., they figured out the government was getting less revenue because tax rates were confiscatory).

A major tax reform in 1991 significantly lowered the top marginal tax rate to encourage growth. The top rate had peaked at 87 percent in 1979 and then gradually dropped to 65 percent in 1990 before being cut to 51 percent in 1991. Subsequent tax increases have since pushed the rate to about 57 percent.

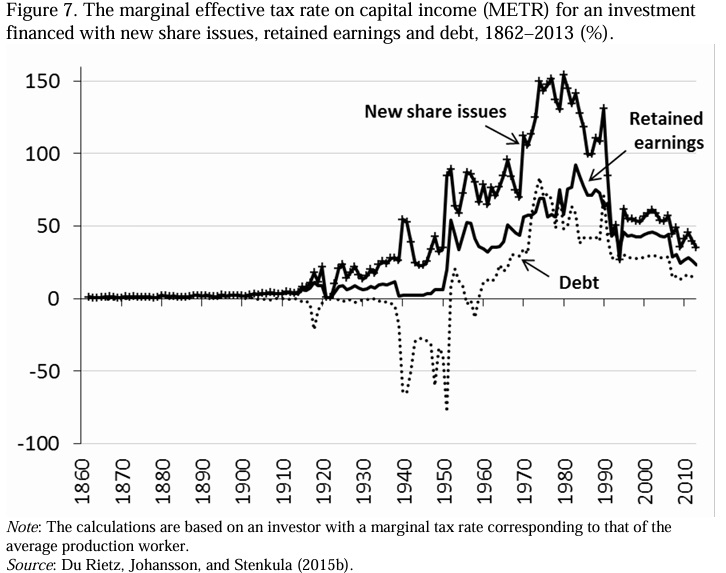

In the interest of fairness, let’s acknowledge that there are a few decent features of the Swedish tax system, including the absence of a death tax or wealth tax, along with a modest tax burden on corporations.

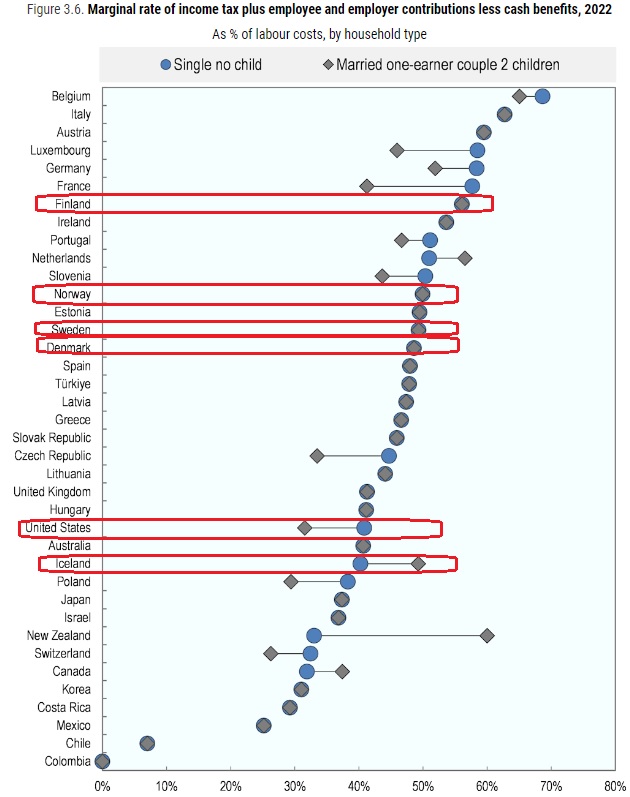

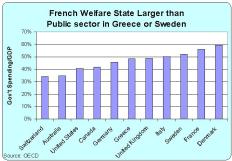

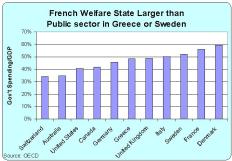

But the bottom line is that Sweden’s overall tax system (and the same can be said of Denmark and other Nordic nations) is oppressive. And the system is oppressive because governments spend too much. Indeed, the welfare state in Sweden and Denmark is as large as the infamous French public sector.

But the bottom line is that Sweden’s overall tax system (and the same can be said of Denmark and other Nordic nations) is oppressive. And the system is oppressive because governments spend too much. Indeed, the welfare state in Sweden and Denmark is as large as the infamous French public sector.

To be sure, the Swedes and Danes partially offset the damage of their big welfare states by having hyper-free market policies in other areas. That’s why they rank much higher than France in Economic Freedom of the World even though all three nations get horrible scores for fiscal policy.

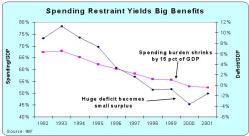

Let’s close by circling back to the main premise of this column. Nima explained that good things happened in the Nordic nations before the welfare state exploded in size.

So I decided to see if we could ratify his hypothesis by checking the growth numbers from the impressive Angus Maddison database. Here’s a chart showing the average growth of per-capita GDP in Denmark and Sweden in the 45 years before 1965 (the year used as an unofficial date for when the welfare state began to metastasize) compared to the average growth of per-capita GDP during the 45 years since 1965.

Unsurprisingly, we find that the economy grew faster and generated more prosperity when government was smaller.

Gee, it’s almost as if there’s a negative relationship between the size of government and the health of the economy? What a novel concept!

P.S. All of which means that there’s still no acceptable response for my two-question challenge to the left.

P.P.S. Both Sweden and Denmark have been good examples for my Golden Rule, albeit only for limited periods.

Read Full Post »

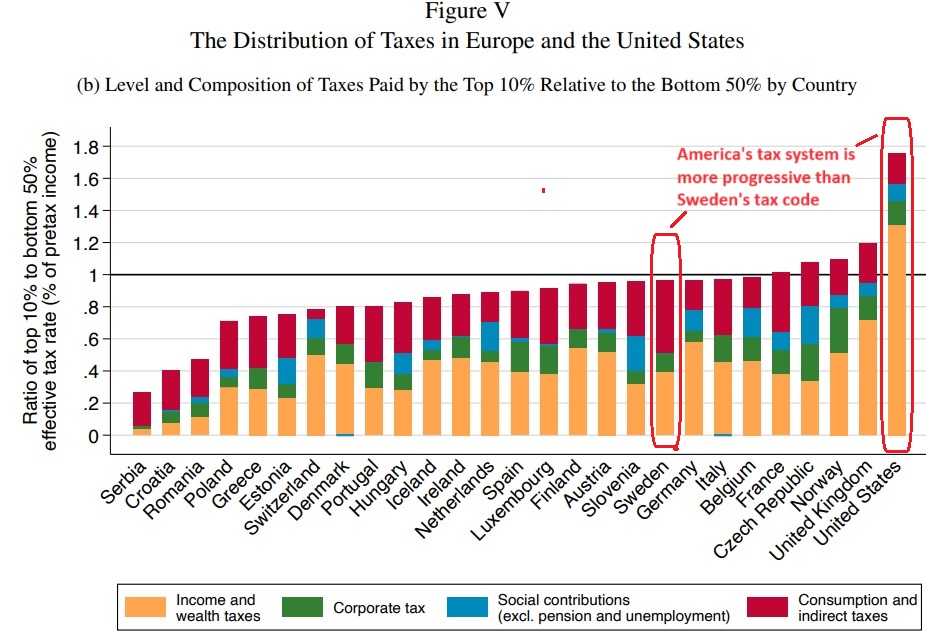

Here’s a chart from a study for the World Inequality Lab by three economists at the Paris School of Economics.

Here’s a chart from a study for the World Inequality Lab by three economists at the Paris School of Economics.Estate tax? In the United States the average effective rate is 16.5 percent. In Sweden, it’s zero. Swedish national sales taxes, which fall disproportionately on the middle classes, are much higher than sales taxes in the United States. …Some scholars have drawn on this history to argue that the United States needs to give up its fixation with progressive taxation and adopt a national sales tax as every other advanced industrial country has done. …It’s hard to make a case for a big new tax in America on the middle classes and the poor…progressive taxation still has a role to play in the United States — but we do need to learn the larger lesson…the secret of the European welfare states.