Donald Trump and other populist leaders frequently are condemned for undermining the “rules-based system” that is the basis of the “postwar order.”

What exactly is meant by this criticism? In the case of Trump, is it disapproval of his protectionism?

Yes, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The broader accusation is that Trump and the others are insufficiently supportive of the so-called “international architecture” of treaties and organizations (the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, World Trade Organization, World Bank, G-7, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, NATO, etc) that western nations created after World War II.

And the critics are right, in my humble opinion.

But that’s besides the point. What’s really needed is a case-by-case analysis to determine whether the aforementioned treaties and organizations are making the world a better place.

To help understand this topic, let’s look at some excerpts from an anonymously authored article in the latest issue of Cayman Financial Review.

What is the oft-cited “postwar order” that ostensibly is being threatened by populism? …begin with some history. There have been three major attempts to create an international architecture in hopes of discouraging war and encouraging peaceful commerce among world’s countries. The first occurred after the Napoleonic wars, the second occurred after World War I, and the third occurred after World War II.

three major attempts to create an international architecture in hopes of discouraging war and encouraging peaceful commerce among world’s countries. The first occurred after the Napoleonic wars, the second occurred after World War I, and the third occurred after World War II.

The article explains that first postwar order was a big success, with 100 years of relative peace and prosperity between 1815 and 1914.

But the second postwar order, which followed World War I, was a miserable failure.

…the urgent economic problems that World War I had created – the need for demobilization, the restoration of the gold standard, the resumption of international trade flows, and the reconstruction of war-ravaged areas. Reparations burdened Germany and contributed to hyperinflation. …Germany depended on American loans to make its reparations payments to France and the United Kingdom. In turn, France and the United Kingdom depended on German reparations to repay their wartime loans from the United States. This financial merry-go-round was inherently unstable. …In the 1930s, many countries tried economic nationalism to escape from the Great Depression. Abandonment of the interwar gold standard, high tariffs to discourage imports, and competitive devaluations to boost exports became widespread. However, these “beggar-thy-neighbor” failed economically, caused the collapse of international trade, and contributed to rising international tensions.

And this grim experience was in the minds of policymakers as they sought to restore a system based on peace and open commerce.

…neither Churchill nor Roosevelt wanted to punish ordinary Germans, Italians or Japanese. Instead of the postwar harshness of Clemenceau, Churchill and Roosevelt favored the postwar magnanimity of Metternich, in which Germany, Italy, and Japan would be reconstructed as democratic capitalist countries. …both Churchill and Roosevelt thought that other new international organizations would be needed to help finance postwar reconstruction, provide stable exchange rates, and promote the progressive liberalization of international trade. …At the risk of oversimplifying, there are four major pieces of what is now loosely though of as the postwar order.

1. The United Nations and other multilateral bodies

2. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank

3. The World Trade Organization and affiliated trade pacts

4. NATO and other military/security alliances

The article is filled with details on how these various institutions evolved.

But for our purposes, let’s focus on ostensible threats to this order. Here’s what “Hamilton” wrote.

All four components of the current international architecture have critics, but they should be examined separately.

- The United Nations is routinely condemned for being ineffective, wasteful and anti-Western. However, the UN part of the post-war order is not under serious threat. However, the OECD is subject to considerable attacks because of its statist policy agenda.

- The IMF and World Bank are routinely condemned for being wasteful and anti-market. The IMF also is singled out for bailout policies that are said to encourage profligacy in developing nation and to reward sloppy lending practices by big western banks. Notwithstanding the instability than many say is caused by the IMF, this part of the postwar order is not under serious threat.

- The WTO and regional FTAs are under threat from a populist backlash in the United States and Europe, driven in large part by angst over financial prospects for lower-skilled workers. This part of the postwar order is under serious threat, especially because U.S. laws give the president significant unilateral powers over trade policy.

- NATO and other security arrangements are being questioned for both cost and changing geopolitical factors (e.g., the rise of China, Islamic terrorism). While unlikely at this point, dramatic policy changes from the United States could substantially alter the structure and/or operation of these military alliances.

How depressing. The part I like is the part that is under assault.

Here are the key points from the article’s conclusion.

The so-called postwar order is not a monolithic entity. …Some have been very successful. Consider, for instance, the sweeping reduction in trade barriers and the concomitant rise in cross-border commerce. …But other parts of the post-war order do not have very strong track records. Bureaucracies such as the IMF and OECD arguably deserve some hostile attention because of their support for anti-market policies. Policymakers who want to preserve the best parts of the post-war order may want to consider whether it is time to jettison or reform the harmful parts.

This is spot on.

Parts of the “postwar order” should be preserved. The World Trade Organization definitely belongs on that list. And presumably nobody wants to disrupt or eliminate the parts of the “international architecture” that facilitate things such as cross-border air travel, international shipping, and global telecommunications.

But the helpful work of those entities doesn’t change the fact that other entities engage in activities that are counterproductive. A “rules-based order” is only good, after all, if it advancing good rules.

Needless to say, the answer to all of these questions is no.

Which brings to mind the old saying about “Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.”

As “Hamilton” wrote, the bad parts of the postwar order should be jettisoned to preserve the good parts.

For those interested in this topic, Adam Tooze of Columbia University has a very interesting article on the same topic.

Published in Foreign Policy, his article basically applies a “public choice” description of how the current postwar order evolved. And he says it initially was not very successful

For true liberals in both the United States and Europe, who hankered after the golden age of globalization in the late 19th century, the resulting Cold War economic order was a profound disappointment. The U.S. Treasury and the first generation of neoliberals in Europe fretted  against the U.S. State Department and its interventionist economic tendencies. Mavericks such as the young Milton Friedman—true advocates of free markets in the way we take for granted today—demanded a bonfire of all regulations. …The reality of the liberal order that supposedly came into existence in the postwar moment was the more or less haphazard continuation of wartime controls. It would take until 1958 before the Bretton Woods vision was finally implemented. Even then it was not a “liberal” order by the standard of the gilded age of the 19th century or in the sense that Davos understands it today. International mobility of capital for anything other than long-term investment was strictly limited.

against the U.S. State Department and its interventionist economic tendencies. Mavericks such as the young Milton Friedman—true advocates of free markets in the way we take for granted today—demanded a bonfire of all regulations. …The reality of the liberal order that supposedly came into existence in the postwar moment was the more or less haphazard continuation of wartime controls. It would take until 1958 before the Bretton Woods vision was finally implemented. Even then it was not a “liberal” order by the standard of the gilded age of the 19th century or in the sense that Davos understands it today. International mobility of capital for anything other than long-term investment was strictly limited.

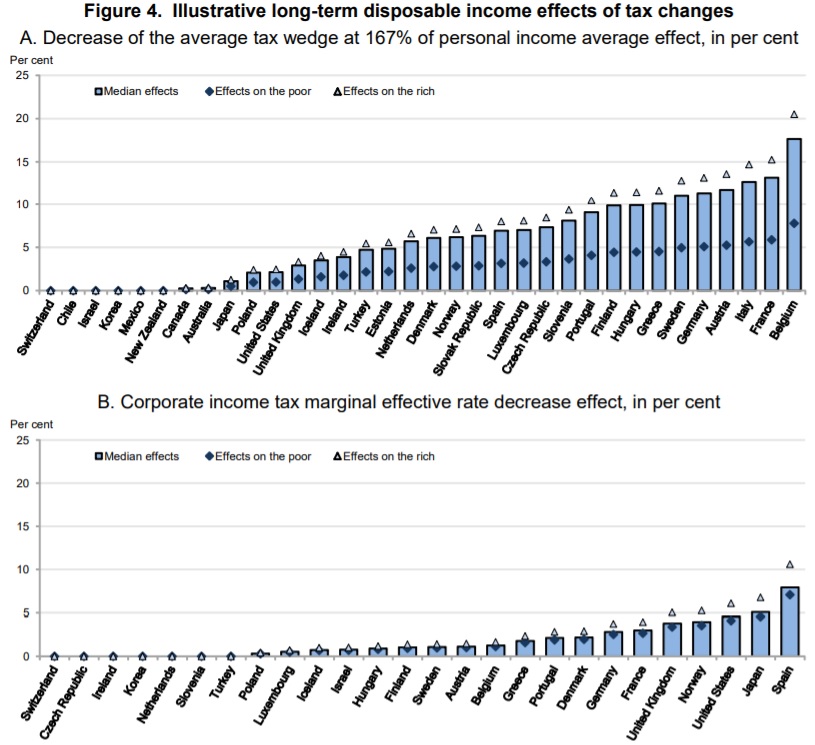

Tooze argues that genuine liberalism (i.e., open markets and trade) didn’t really take hold until the 1980s, with the market-based revolution of Thatcher and Reagan, the “Washington Consensus,” and the collapse of communism.

The stakeholders in the 1970s were obstreperous trade unions, and that kind of consultation was precisely the bad habit that the neoliberal revolutionaries set out to break. …the global victory of the liberal order required a more far-reaching struggle. …the market revolution of the 1980s… the aftermath of the Cold War, the moment of Western triumph. …the defeat of inflation, this was the age of the Washington Consensus.

For those not familiar with this particular piece of jargon, the “Washington Consensus” refers to the 1980s-era acceptance of free markets as the ideal route for economic development.

And “neoliberal” refers to classical liberalism, not the modern dirigiste version of liberalism found in the United States.

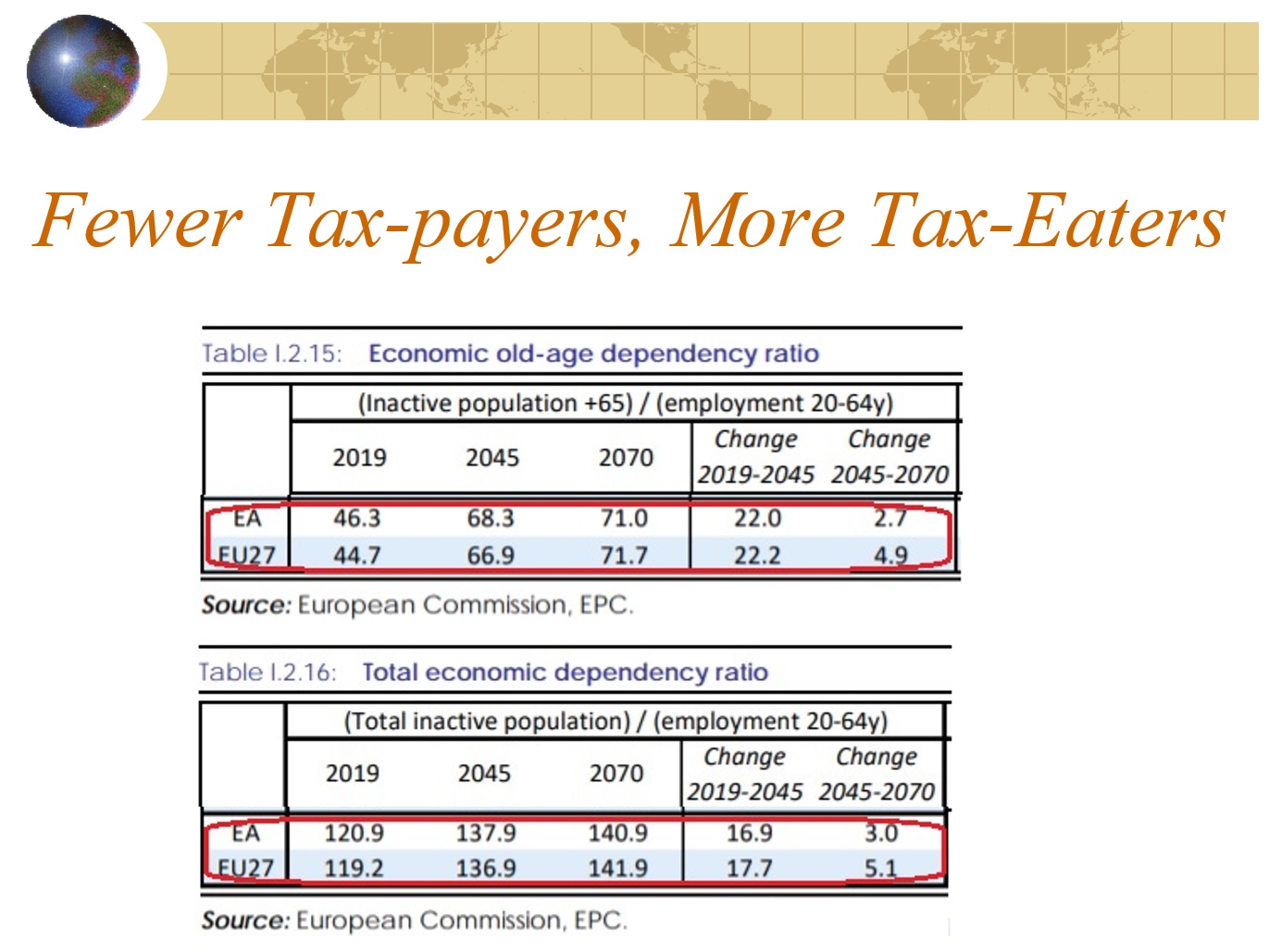

I’ll close by recycling this visual, which attempts to distinguish between good globalism and bad globalism.

The image uses the example of trade and jurisdictional competition, so I don’t pretend is captures all the issues and controversies that we discussed today.

But it reinforces why it is wrong to blindly accept and support the anti-market components of the postwar order simply because there are other parts that deserve our support. The goal is more global prosperity, not less.

Read Full Post »

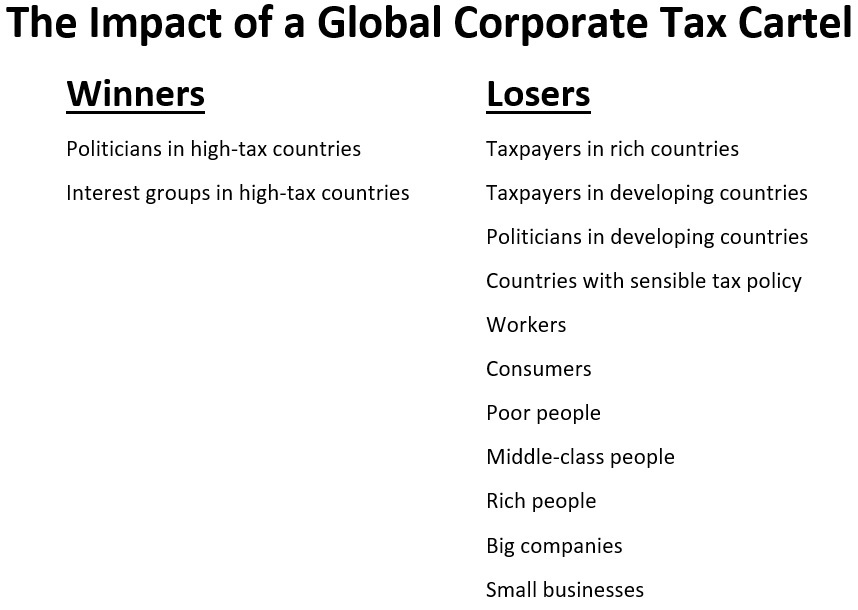

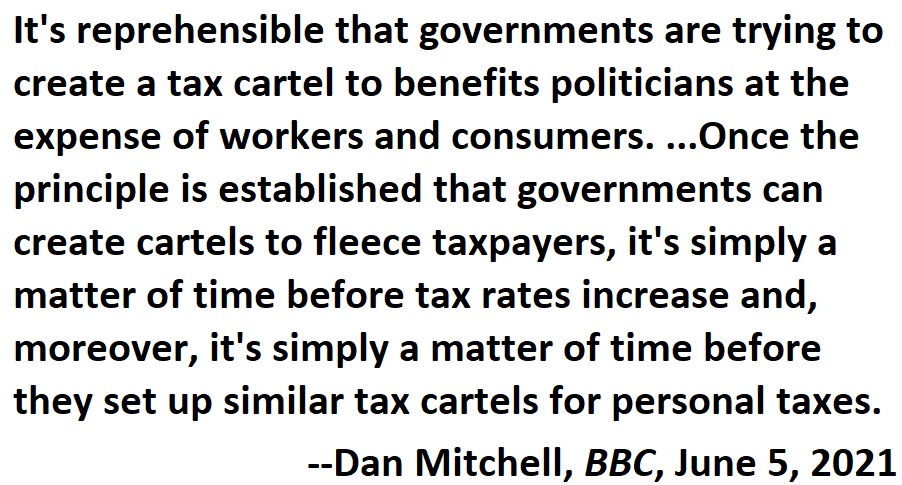

Especially the threat of financial protectionism.

Especially the threat of financial protectionism.

Aiming to build on the cooperation that resulted in a 15% global minimum tax on multinational companies, which came into effect in January, the plan is being promoted under Brazil’s presidency of the G20… Brazil’s finance minister, Fernando Haddad, under the leftwing government of the president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, is pushing for the adoption of the policy. France’s finance minister, Bruno Le Maire, also gave his backing this week, saying Europe should take it forward. …Zucman said the G20 talks would mark “the beginning of a conversation”. Various details would need to be hammered out between countries.