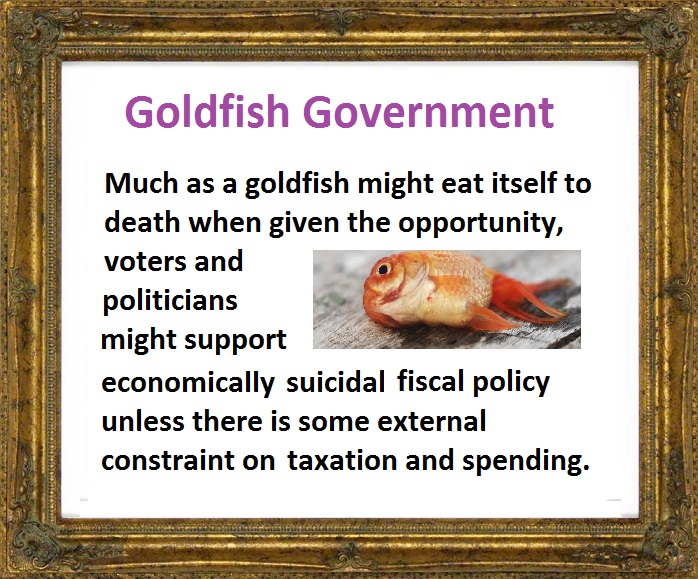

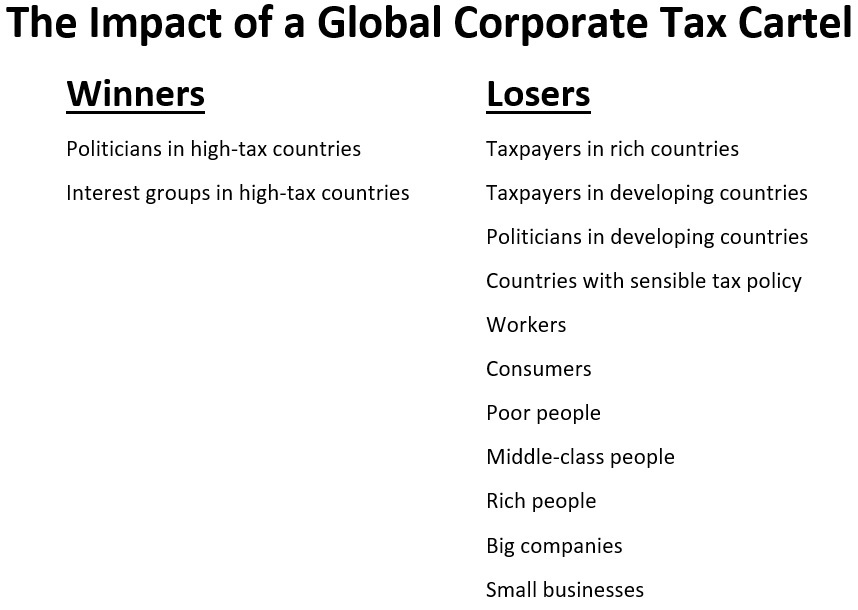

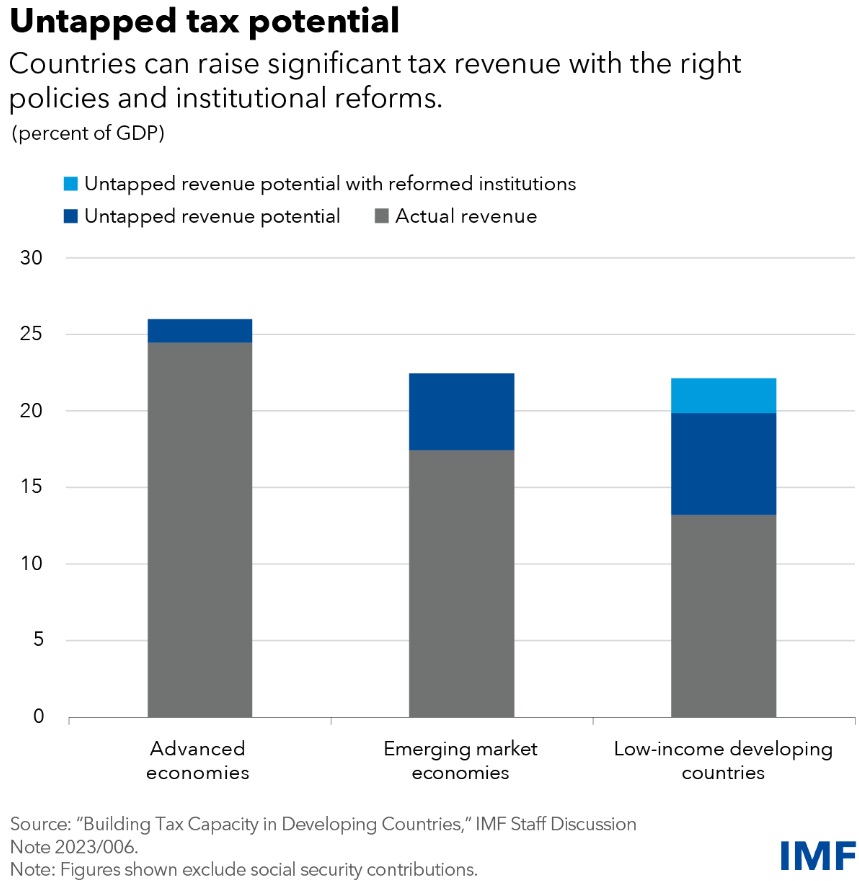

Like other international bureaucracies (most notably the IMF and OECD), the United Nations routinely advocates for higher taxes.

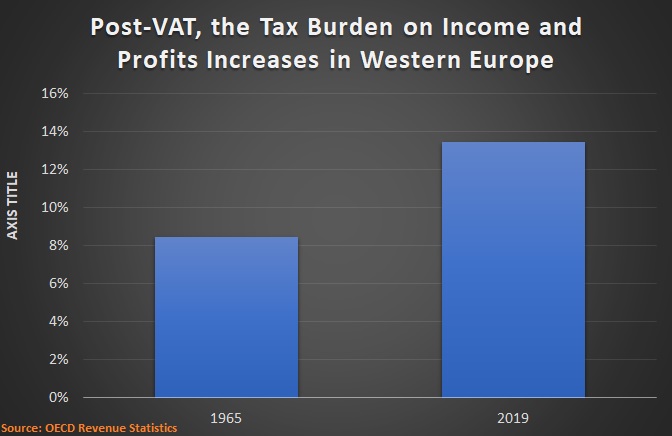

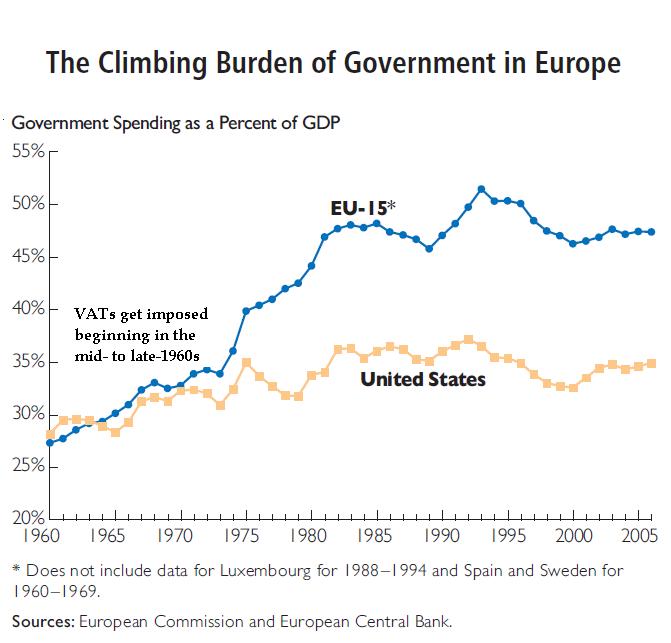

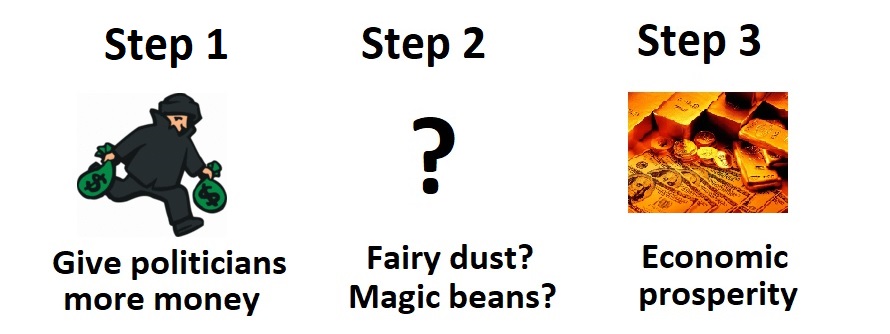

According to the bureaucrats, we are supposed to believe that higher taxes are necessary because a bigger burden of government will increase growth.

According to the bureaucrats, we are supposed to believe that higher taxes are necessary because a bigger burden of government will increase growth.

I’m not joking. The Center for Freedom and Prosperity produced a video outlining – and debunking – this silly theory.

What’s especially galling is that international bureaucrats at places like the U.N. get tax-free salaries, so they are exempt from the negative impact of the bad policies they want for everyone else.

I’ve sometimes speculated that they might have a more sensible attitude if they had to pay tax.

Well, we now have a test case. In an article for ABC News, Deng Machol writes about the U.N. deciding that taxes are a bad idea.

Following an appeal from the United Nations, South Sudan removed recently imposed taxes and fees that had triggered suspension of U.N. food airdrops. Thousands of people in the country depend on aid from the outside. The U.N. earlier this week urged South Sudanese authorities to remove the new taxes, introduced in February.

The measures applied to charges for electronic cargo tracking, security escort fees and fuel. …The U.N said the new measures would have increased the mission’s monthly operational costs to $339,000. The U.N. food air drops feed over 16,300 people every month. At the United Nations in New York, U.N. spokesman Stéphane Dujarric said the taxes and charges would also impact the nearly 20,000-strong U.N. peacekeeping mission in South Sudan, “which is reviewing all of its activities, including patrols, the construction of police stations, schools and centers, as well as educational support.”

What a revelation. The U.N. suddenly realizes that higher taxes decrease whatever is being taxed. The “philoso-raptor” won’t be surprised.

Maybe, just maybe, the bureaucrats will now realize that high taxes on the rest of us also are a bad idea.

But I won’t hold my breath. After all, some (untaxed) bureaucrats at the United Nation think it is a violation of human rights if the rest of us don’t pay more tax.

P.S. As you might suspect, the U.N. budget has plenty of waste.

P.P.S. I had the surreal experience of being a credentialed observer at a United Nations conference where it seemed like I was the only person who did not favor higher taxes.