With their punitive proposals for wealth taxes, Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren are leading the who-can-be-craziest debate in the Democratic Party.

in the Democratic Party.

But what would happen if either “Crazy Bernie” or “Looney Liz” actually had the opportunity to impose such levies?

At the risk of gross understatement, the effect won’t be pretty.

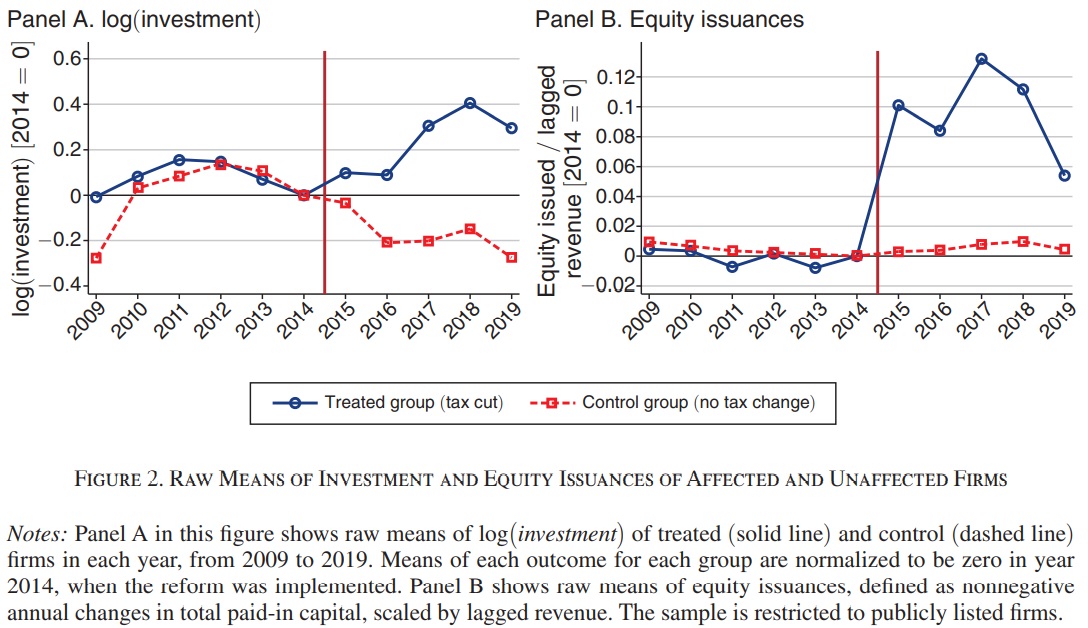

Based on what’s happened elsewhere in Europe, the Wall Street Journal opined that America’s economy would suffer.

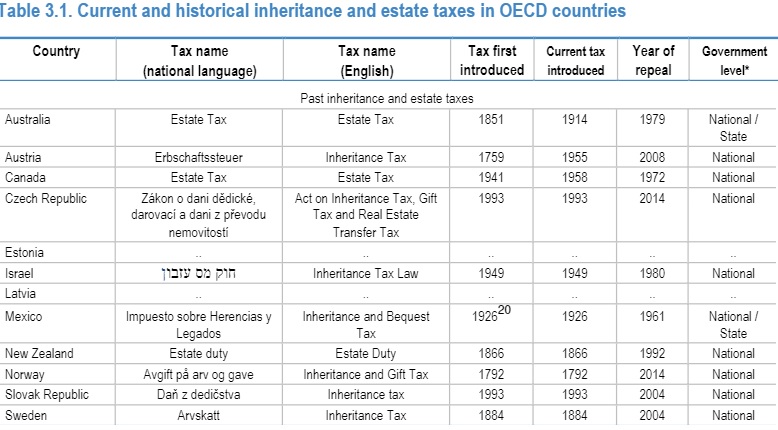

Bernie Sanders often points to Europe as his economic model, but there’s one lesson from the Continent that he and Elizabeth Warren want to ignore. Europe has tried and mostly rejected the wealth taxes that the two presidential candidates are now promising for America. …Sweden…had a wealth tax for most of the 20th century, though its revenue never accounted for more than 0.4% of gross domestic product in the postwar era. …The relatively small Swedish tax still was enough of a burden to drive out some of the country’s brightest citizens. …In 2007 the government repealed its 1.5% tax on personal wealth over $200,000. …Germany…imposed levies of 0.5% and 0.7% on personal and corporate wealth in 1978. The rate rose to 1% in 1995, but the Federal Constitutional Court struck down the wealth tax that year, and it was effectively abolished by 1997. …The German left occasionally proposes resurrecting the old system, and in 2018 the Ifo Institute for Economic Research analyzed how that would affect the German economy. The authors’ baseline scenario suggests that long-run GDP would be 5% lower with a wealth tax, while employment would shrink 2%. …The best argument against a wealth tax is moral. It is a confiscatory tax on the assets from work, thrift and investment that have already been taxed at least once as individual or corporate income, and perhaps again as a capital gain or death tax. The European experience shows that it also fails in practice.

…The relatively small Swedish tax still was enough of a burden to drive out some of the country’s brightest citizens. …In 2007 the government repealed its 1.5% tax on personal wealth over $200,000. …Germany…imposed levies of 0.5% and 0.7% on personal and corporate wealth in 1978. The rate rose to 1% in 1995, but the Federal Constitutional Court struck down the wealth tax that year, and it was effectively abolished by 1997. …The German left occasionally proposes resurrecting the old system, and in 2018 the Ifo Institute for Economic Research analyzed how that would affect the German economy. The authors’ baseline scenario suggests that long-run GDP would be 5% lower with a wealth tax, while employment would shrink 2%. …The best argument against a wealth tax is moral. It is a confiscatory tax on the assets from work, thrift and investment that have already been taxed at least once as individual or corporate income, and perhaps again as a capital gain or death tax. The European experience shows that it also fails in practice.

Karl Smith’s Bloomberg column warns that wealth taxes would undermine the entrepreneurial capitalism that has made the United States so successful.

…a wealth tax…would allow the federal government to undermine a central animating idea of American capitalism. …The U.S. probably could design a wealth tax that works. …If a country was harboring runaway billionaires, the U.S. could effectively lock it out of the international financial system. That would make it practically impossible for high-net-worth people to have control over their wealth, even if it they could keep the U.S. government from collecting it. The necessity of this type of harsh enforcement points to a much larger flaw in the wealth tax… Billionaires…accumulate wealth…it allows them to control the destiny of the enterprises they founded. A wealth tax stands in the way of this by requiring billionaires to sell off stakes in their companies to pay the tax. …One of the things that makes capitalism work is the way it makes economic resources available to those who have demonstrated an ability to deploy them effectively. It’s the upside of billionaires. …A wealth tax designed to democratize control over companies would strike directly at this strength. …a wealth tax would penalize the founders with the most dedication to their businesses. Entrepreneurs would be less likely to start businesses, in Silicon Valley or elsewhere, if they think their success will result in the loss of their ability to guide their company.

even if it they could keep the U.S. government from collecting it. The necessity of this type of harsh enforcement points to a much larger flaw in the wealth tax… Billionaires…accumulate wealth…it allows them to control the destiny of the enterprises they founded. A wealth tax stands in the way of this by requiring billionaires to sell off stakes in their companies to pay the tax. …One of the things that makes capitalism work is the way it makes economic resources available to those who have demonstrated an ability to deploy them effectively. It’s the upside of billionaires. …A wealth tax designed to democratize control over companies would strike directly at this strength. …a wealth tax would penalize the founders with the most dedication to their businesses. Entrepreneurs would be less likely to start businesses, in Silicon Valley or elsewhere, if they think their success will result in the loss of their ability to guide their company.

The bottom line, given the importance of “super entrepreneurs” to a nation’s economy, is that wealth taxes would do considerable long-run damage.

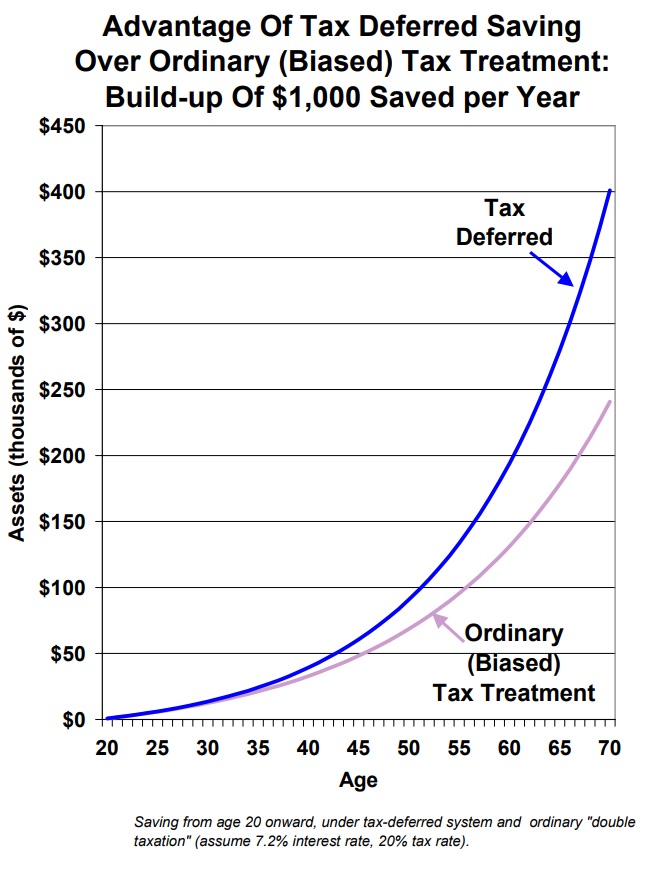

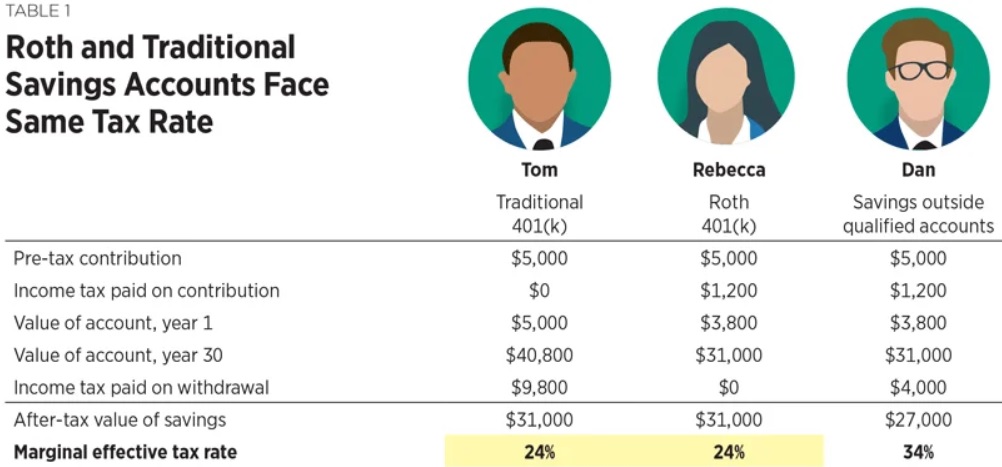

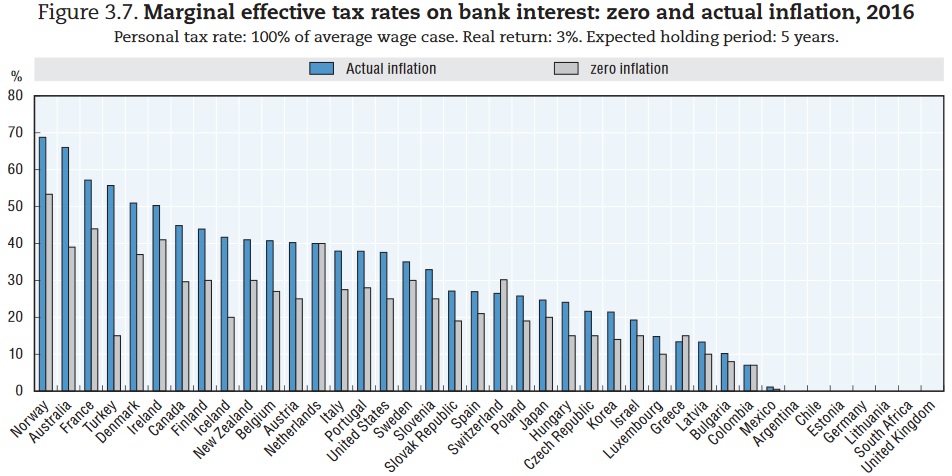

Andy Kessler, in a column for the Wall Street Journal, explains that wealth taxes directly harm growth by penalizing income that is saved and invested.

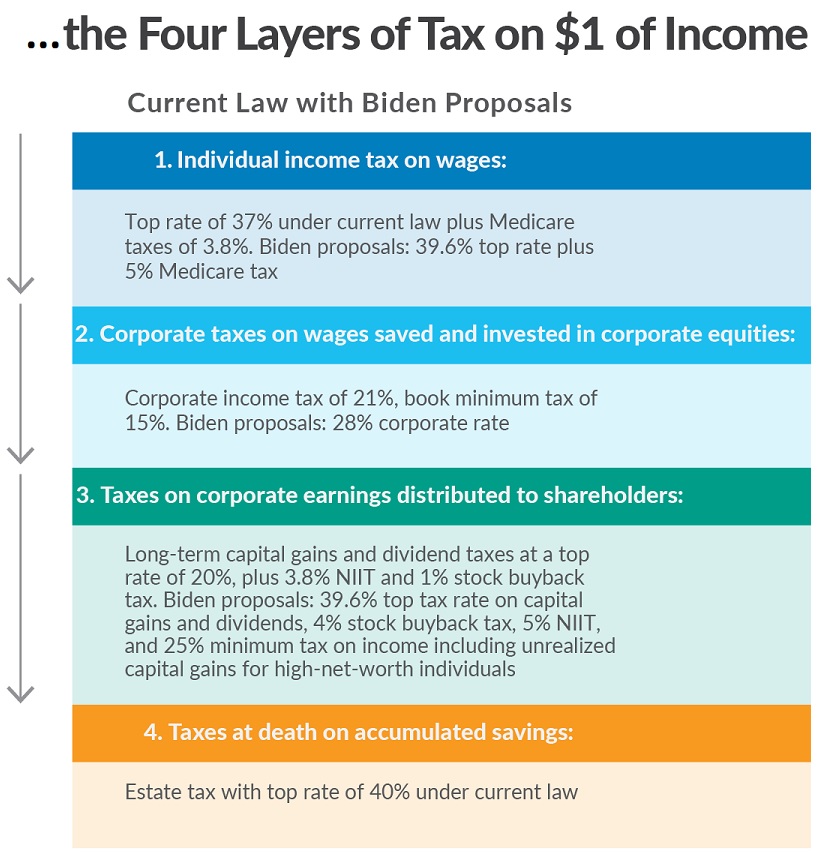

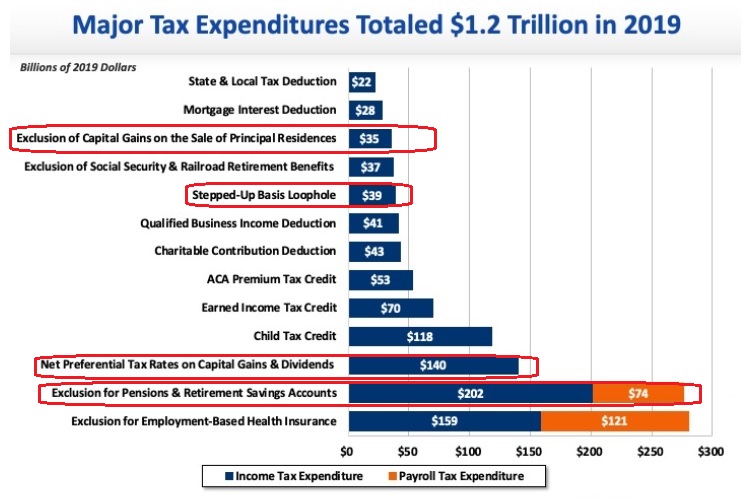

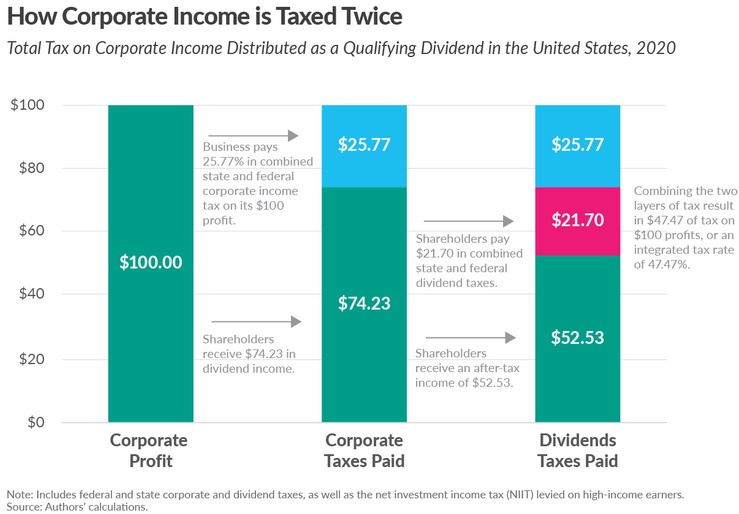

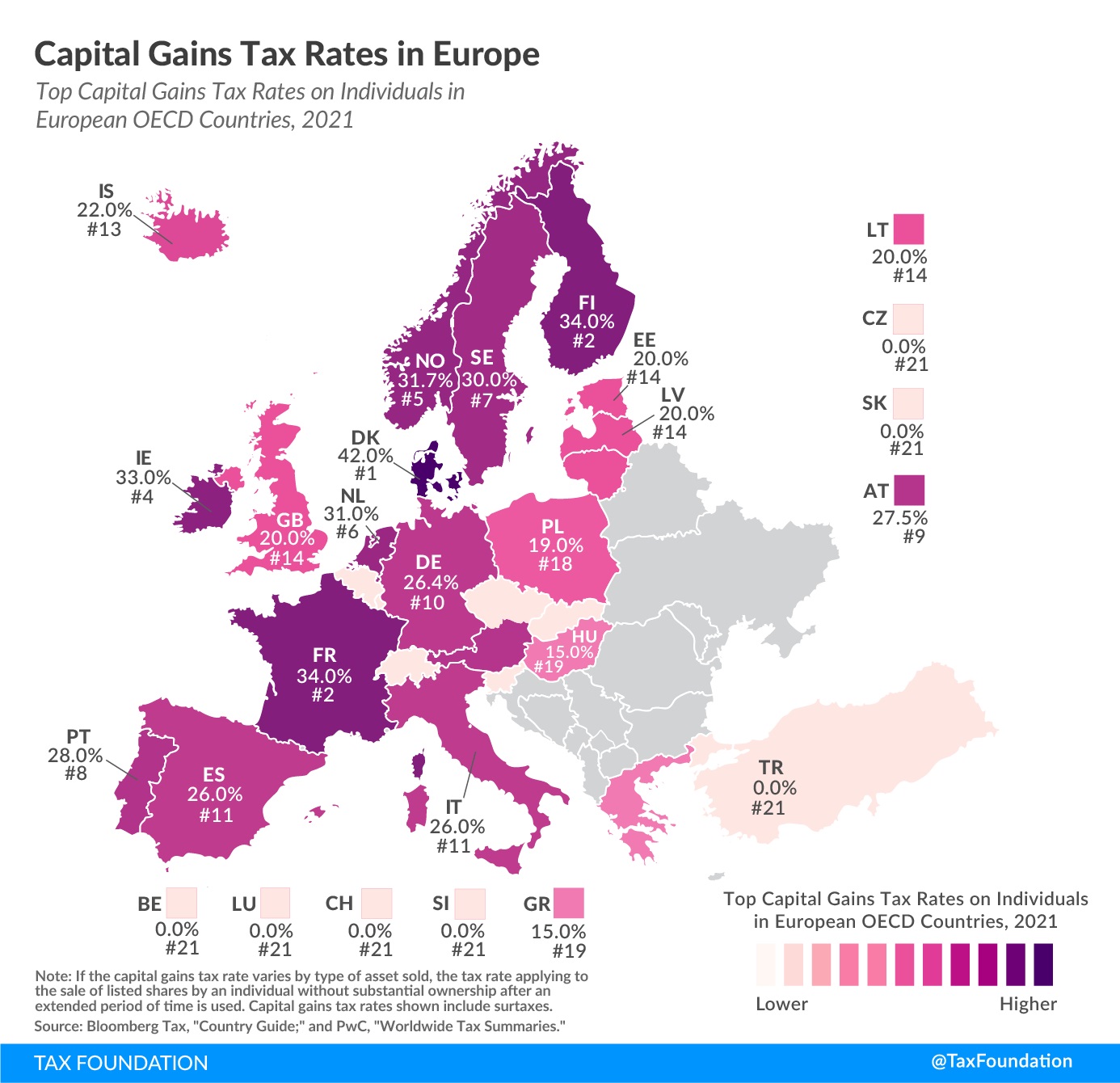

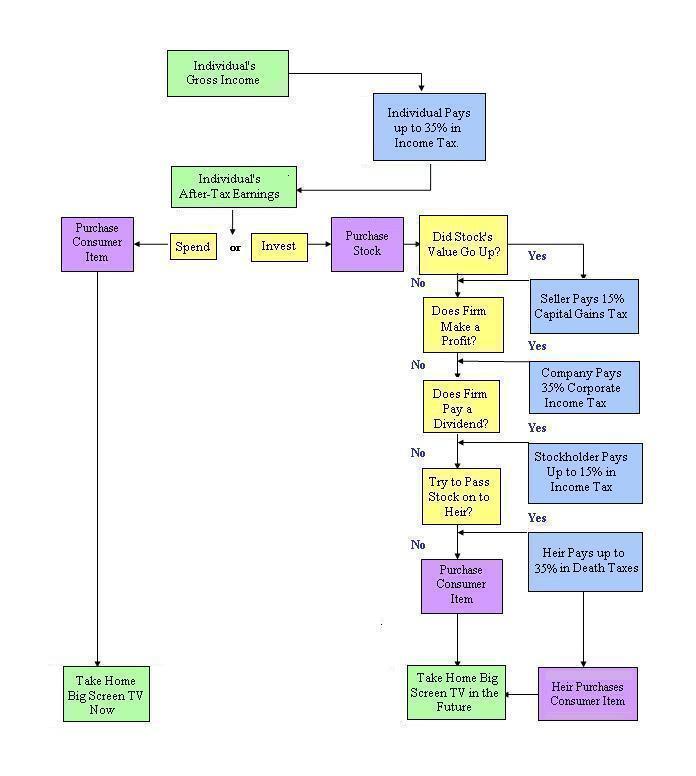

Even setting comical revenue projections aside, the wealth-tax idea doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Never mind that it’s likely unconstitutional. Or that a wealth tax is triple taxation… The most preposterous part of the wealth-tax plans is their supporters’ insistence that they would be good for the economy. …a wealth tax would suck money away from productive investments. …liberals in favor of taxation always trot out the tired trope that the poor drive growth by spending their money while the rich hoard it, tossing gold coins in the air in their basement vaults. …So just tax the rich and government spending will create great jobs for the poor and middle class. This couldn’t be more wrong. As anyone with $1 billion—or $1,000—knows, people don’t stuff their mattresses with Benjamins. They invest them. …most likely…in stocks or invested directly in job-creating companies… A wealth tax takes money out of the hands of some of the most productive members of society and directs it toward the least productive uses. …existing taxes on interest, dividends and capital gains discourage the healthy savings that create jobs in the economy. These are effectively taxes on wealth—and we don’t need another one.

…liberals in favor of taxation always trot out the tired trope that the poor drive growth by spending their money while the rich hoard it, tossing gold coins in the air in their basement vaults. …So just tax the rich and government spending will create great jobs for the poor and middle class. This couldn’t be more wrong. As anyone with $1 billion—or $1,000—knows, people don’t stuff their mattresses with Benjamins. They invest them. …most likely…in stocks or invested directly in job-creating companies… A wealth tax takes money out of the hands of some of the most productive members of society and directs it toward the least productive uses. …existing taxes on interest, dividends and capital gains discourage the healthy savings that create jobs in the economy. These are effectively taxes on wealth—and we don’t need another one.

Professor Noah Smith leans to the left. But that doesn’t stop him, in a column for Bloomberg, from looking at what happened in France and then warning that wealth taxes have some big downsides.

Studies on the effects of taxation when rates are moderate might not be a good guide to what happens when rates are very high. Economic theories tend to make a host of simplifying assumptions that might break down under a very high-tax regime. …One way to predict the possible effects of the taxes is to look at a country that tried something similar: France, where Piketty, Saez and Zucman all hail from.  …France…shows that inequality, at least to some degree, is a choice. Taxes and spending really can make a big difference. But there’s probably a limit to how much even France can do in this regard. The country has experimented with…wealth taxes…with disappointing results. France had a wealth tax from 1982 to 1986 and again from 1988 to 2017. …The wealth tax might have generated social solidarity, but as a practical matter it was a disappointment. The revenue it raised was rather paltry; only a few billion euros at its peak, or about 1% of France’s total revenue from all taxes. At least 10,000 wealthy people left the country to avoid paying the tax; most moved to neighboring Belgium… France lost not only their wealth tax revenue but their income taxes and other taxes as well. French economist Eric Pichet estimates that this ended up costing the French government almost twice as much revenue as the total yielded by the wealth tax.

…France…shows that inequality, at least to some degree, is a choice. Taxes and spending really can make a big difference. But there’s probably a limit to how much even France can do in this regard. The country has experimented with…wealth taxes…with disappointing results. France had a wealth tax from 1982 to 1986 and again from 1988 to 2017. …The wealth tax might have generated social solidarity, but as a practical matter it was a disappointment. The revenue it raised was rather paltry; only a few billion euros at its peak, or about 1% of France’s total revenue from all taxes. At least 10,000 wealthy people left the country to avoid paying the tax; most moved to neighboring Belgium… France lost not only their wealth tax revenue but their income taxes and other taxes as well. French economist Eric Pichet estimates that this ended up costing the French government almost twice as much revenue as the total yielded by the wealth tax.

In other words, the much-maligned Laffer Curve is very real. When looking at total tax collections from the rich, the wealth tax resulted in less money for France’s greedy politicians.

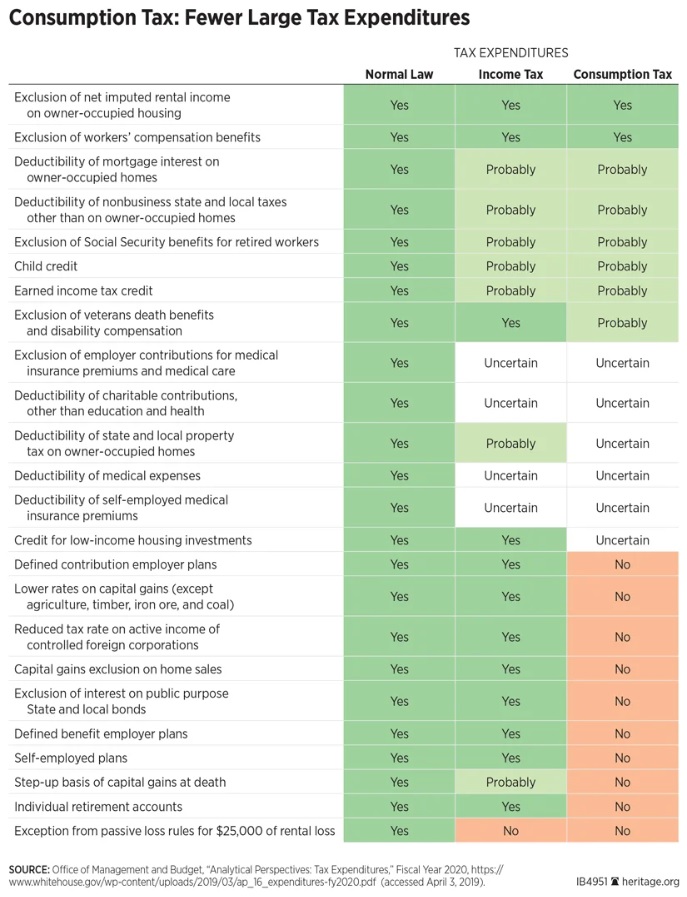

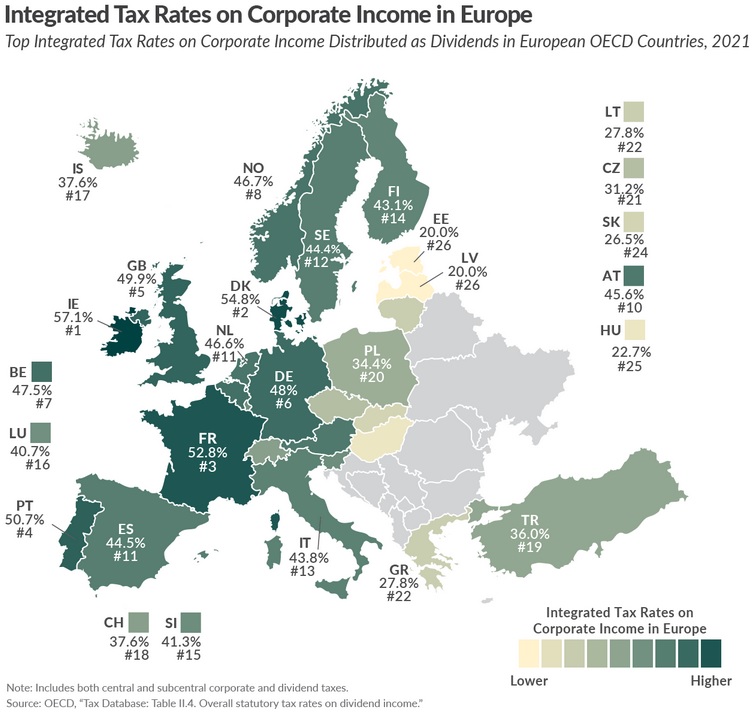

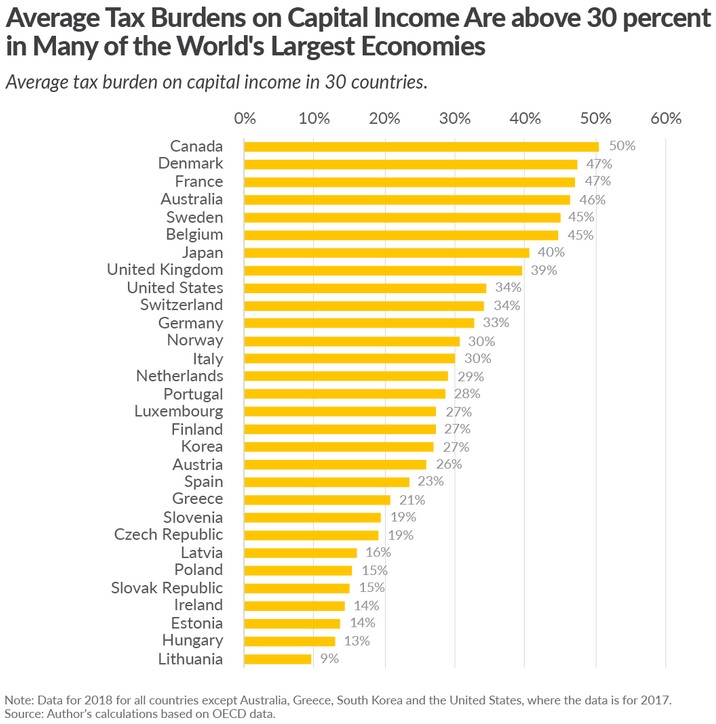

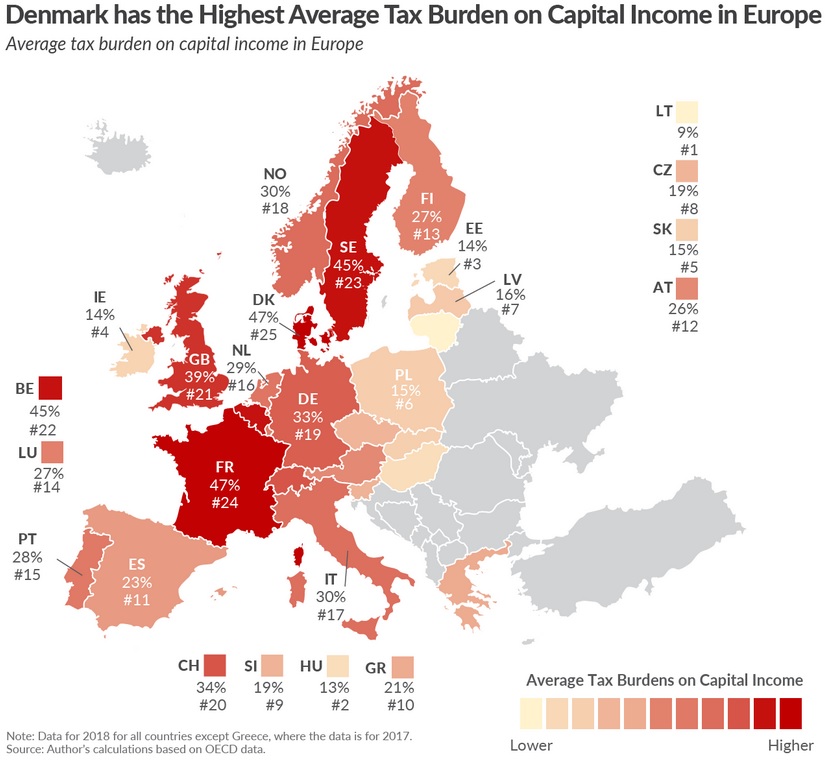

And this chart from the column shows that French lawmakers are experts at extracting money from the private sector.

The dirty little secret, of course, is that lower-income and middle-class taxpayers are the ones being mistreated.

By the way, Professor Smith’s column also notes that President Hollande’s 75 percent tax rate on the rich also backfired.

Let’s close with a report from the Wall Street Journal about one of the grim implications of Senator Warren’s proposed tax.

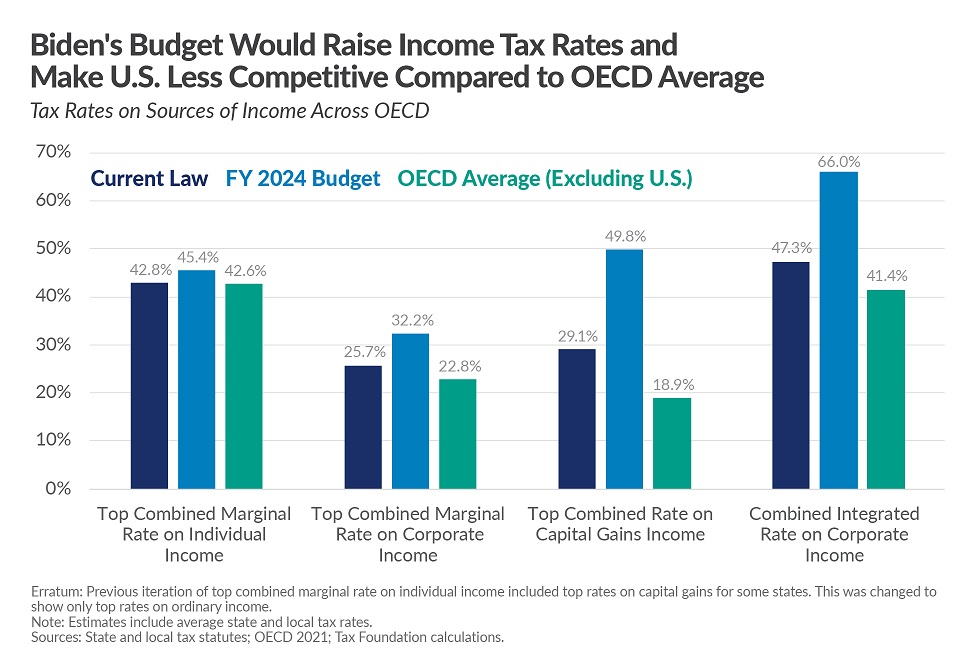

Elizabeth Warren has unveiled sweeping tax proposals that would push federal tax rates on some billionaires and multimillionaires above 100%. That prospect raises questions for taxpayers and the broader economy… How might that change their behavior? And would investment and economic growth suffer? …The rate would vary according to the investor’s circumstances, any state taxes, the profitability of his investments and as-yet-unspecified policy details, but tax rates of over 100% on investment income would be typical, especially for billionaires. …After Ms. Warren’s one-two punch, some billionaires who generate pretax returns could pay annual taxes that would leave them with less money than they started with.

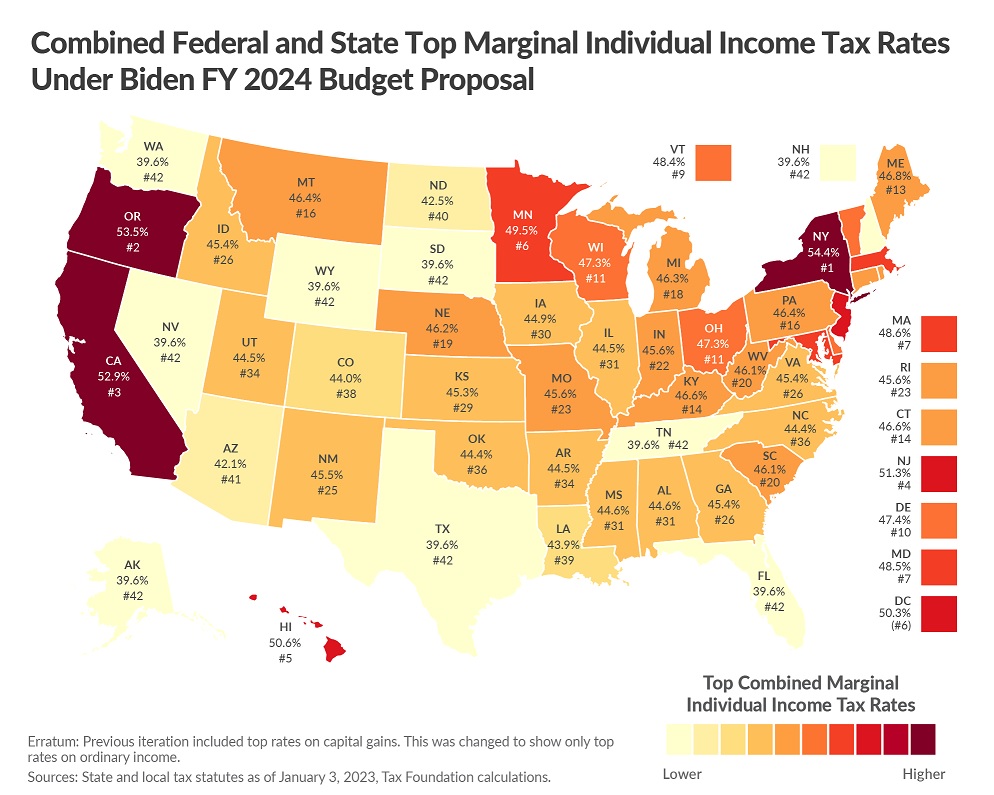

And would investment and economic growth suffer? …The rate would vary according to the investor’s circumstances, any state taxes, the profitability of his investments and as-yet-unspecified policy details, but tax rates of over 100% on investment income would be typical, especially for billionaires. …After Ms. Warren’s one-two punch, some billionaires who generate pretax returns could pay annual taxes that would leave them with less money than they started with.

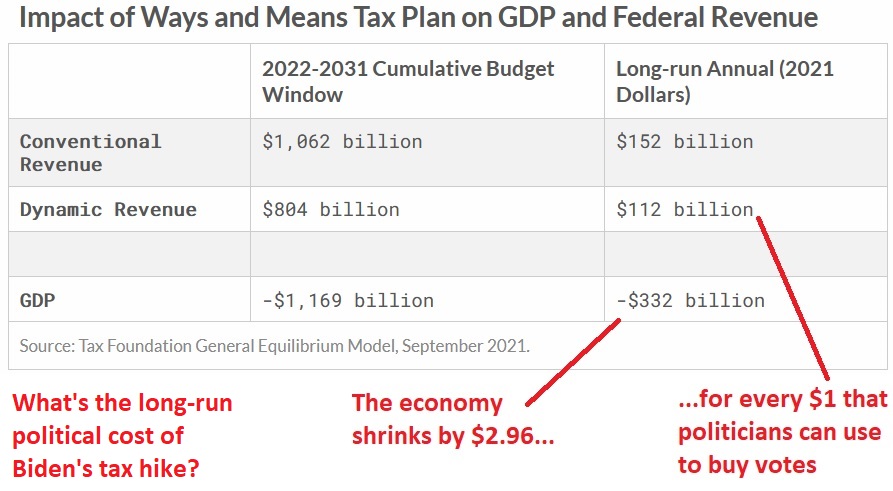

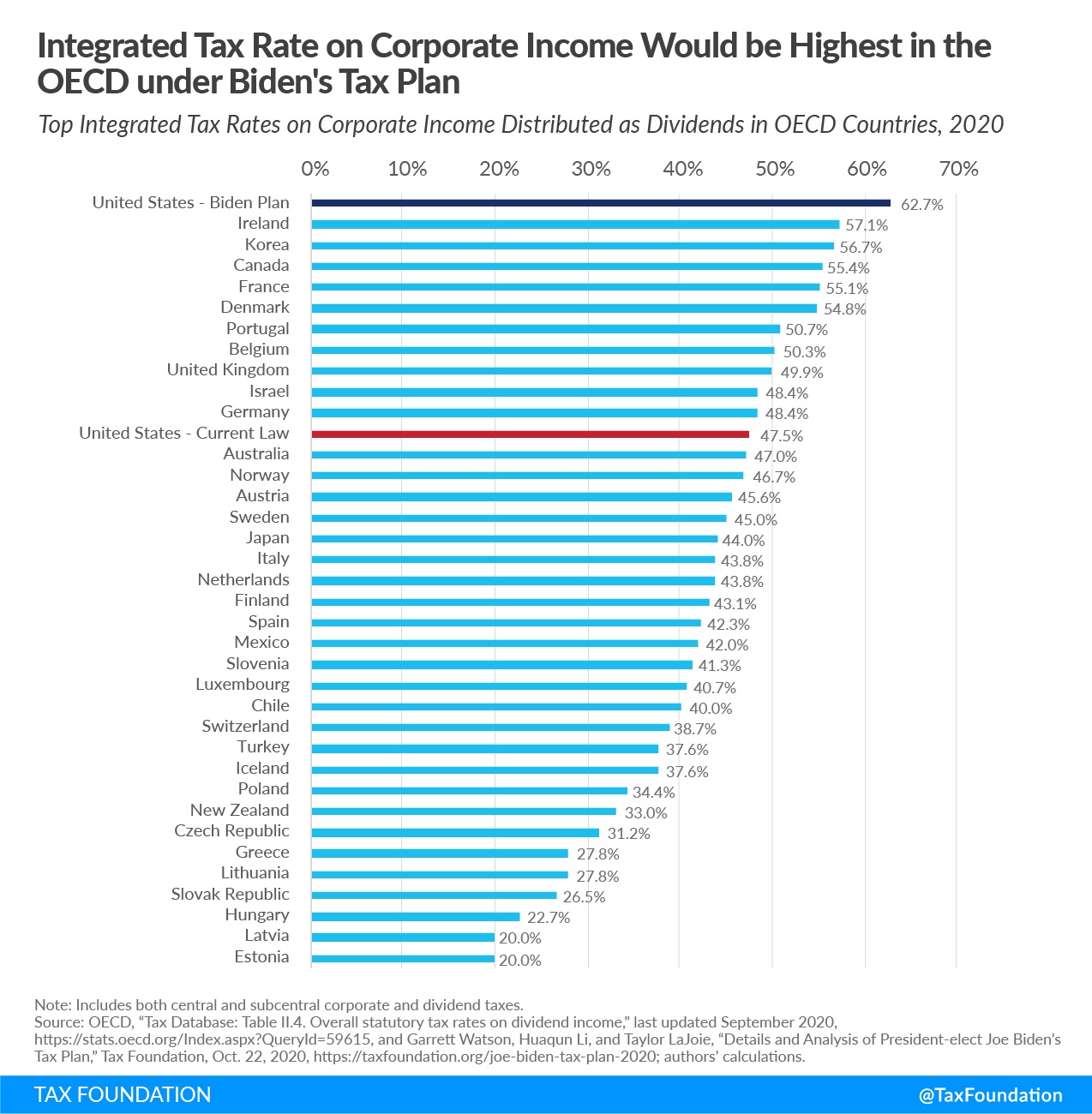

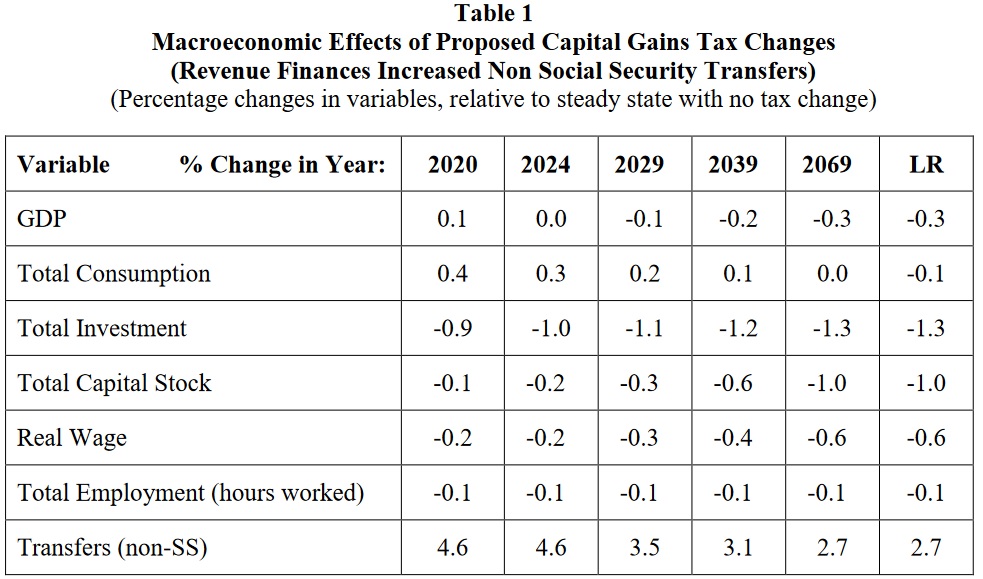

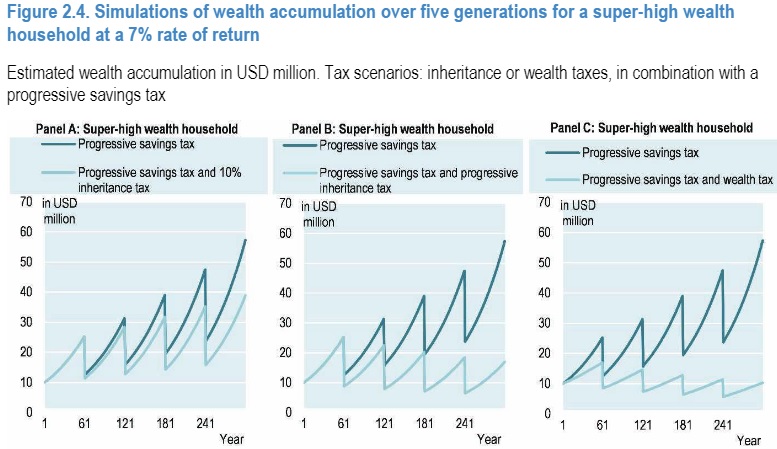

Here’s a chart from the story (which I’ve modified in red for emphasis) showing that investors would face effective tax rates of more than 100 percent unless they somehow managed to earn very high returns.

For what it’s worth, I’ve been making this same point for many years, starting in 2012.

Nonetheless, I’m glad to see it’s finally getting traction. Hopefully this will deter lawmakers from ever imposing such a catastrophically bad policy.

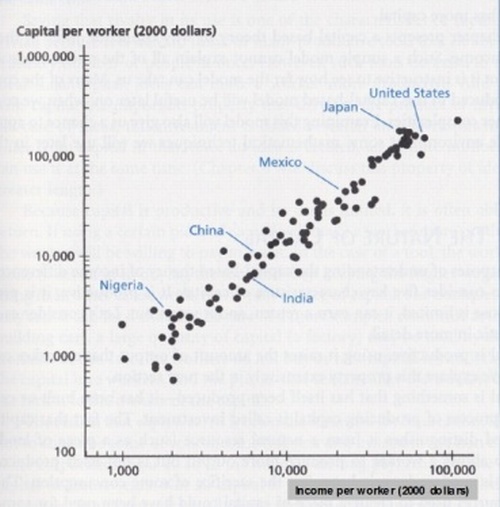

Remember, a tax that discourages saving and investment is a tax that results in lower wages for workers.

P.S. Switzerland has the world’s best-functioning wealth tax (basically as an alternative to other forms of double taxation), but even that levy is destructive and should be abolished.

P.P.S. Sadly, because their chief motive is envy, I don’t think my left-leaning friends can be convinced by data about economic damage.

Read Full Post »

But he owns roughly 10 percent of the company, which made a profit of $30 billion in 2023. …Unless Mr. Bezos, Warren Buffett or Elon Musk sell their stock, their taxable income is relatively minuscule. …There is a way to make tax dodging less attractive: a global minimum tax. …The idea is simple. Let’s agree that billionaires should pay income taxes equivalent to a small portion — say, 2 percent — of their wealth each year. …the proposal would allow countries to collect an estimated $250 billion in additional tax revenue per year, which is even more than what the global minimum tax on corporations is expected to add.

this would principally be a tax raid on Americans, who are the most numerous billionaires. It would also be taxation without representation, since it would be a body of global elites attempting to impose a tax without having passed Congress. …Once a global wealth tax is in place, you can be sure that billionaires won’t be the last target. …the G-20 is becoming a vehicle for the world’s left-wing governments to gang up on the U.S. …For this crowd, taxing American billionaires to redistribute income around the world is all too imaginable.