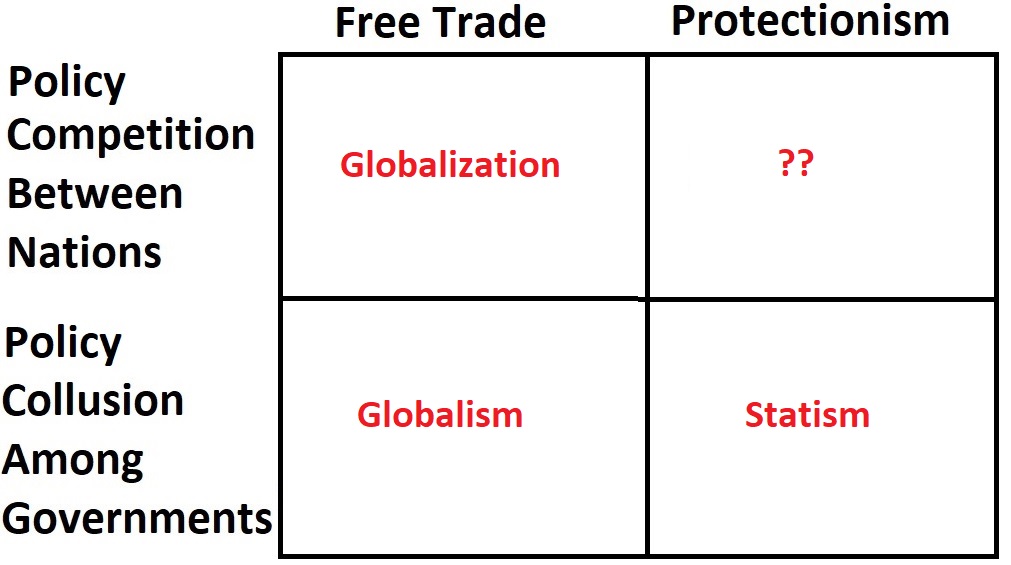

Libertarians and other supporters of limited government historically have mixed feelings about the European Union (and its various governmental manifestations).

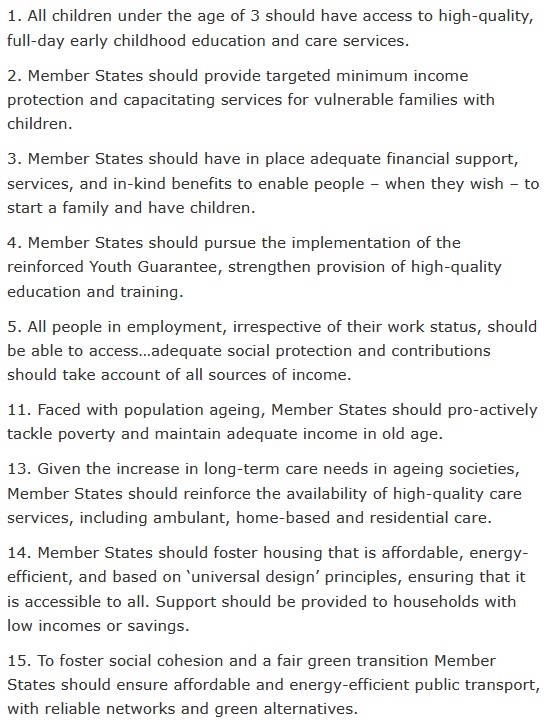

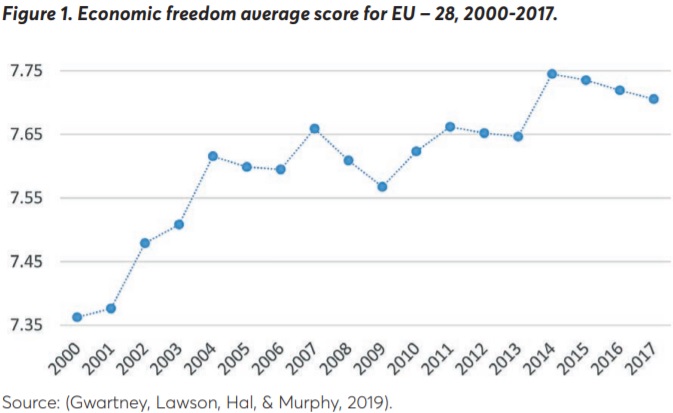

On the plus side, there are no trade barriers between nations that belong to the EU, and membership also makes it difficult for countries to impose  regulatory burdens that hinder trade. The EU also has helped to improve the rule of law in some nations, particularly for newer members from the former Soviet Bloc.

regulatory burdens that hinder trade. The EU also has helped to improve the rule of law in some nations, particularly for newer members from the former Soviet Bloc.

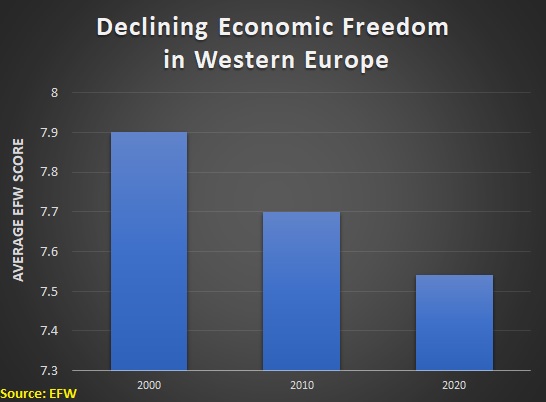

On the minus side, the EU imposes trade barriers against the rest of the world. There is also continuous pressure for tax harmonization policies and regulatory harmonization policies that increase the burden of government – compounded by efforts to export those bad polices to non-member nations.

Given these good and bad features, it’s understandable that proponents of economic liberty don’t have a consensus position on the European Union.

But views may become more universally hostile since some European politicians now want to use the coronavirus crisis as an excuse to expand redistribution and enable bailouts by changing existing EU rules.

Currently, there is very limited scope for bad European-wide fiscal policy because Article 125 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ostensibly prohibits cross-country redistribution or bailouts.

For what it’s worth, there is another provision for nations that use the euro currency. Article 136 of the Treaty allows for a “stability mechanism” to “safeguard the stability of the euro,” but also states that “the mechanism will be made subject to strict conditionality.”

Now let’s apply this background knowledge to the current situation.

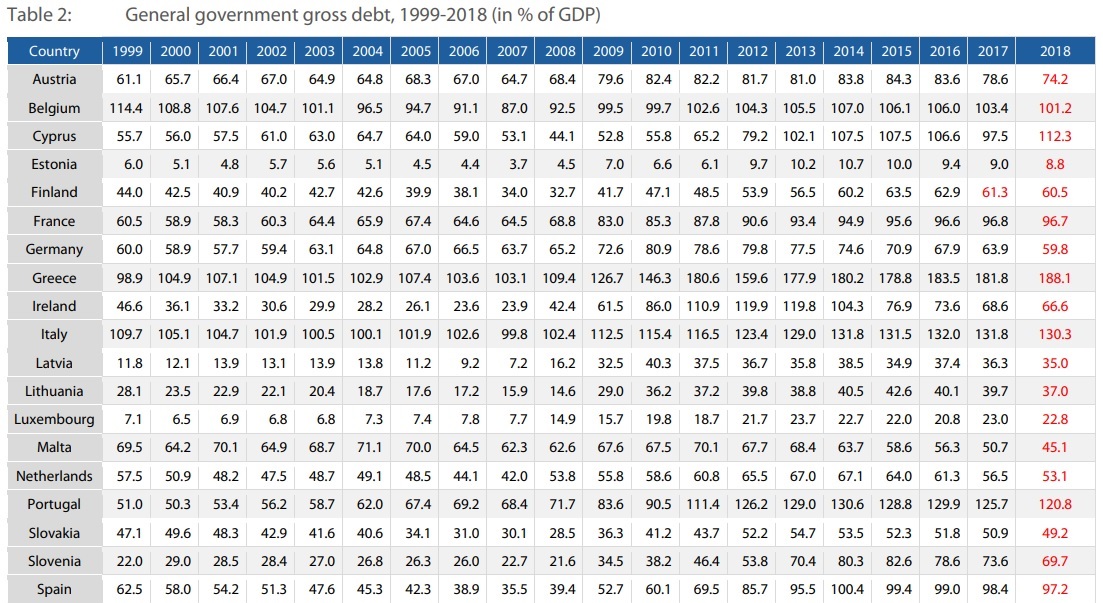

As I wrote last month, the coronavirus-triggered economic mess is wreaking havoc with the finances of EU nations, especially for “Club Med” nations.

For example, Desmond Lachman of the American Enterprise Institute writes for the Hill about the potential consequences for Italy.

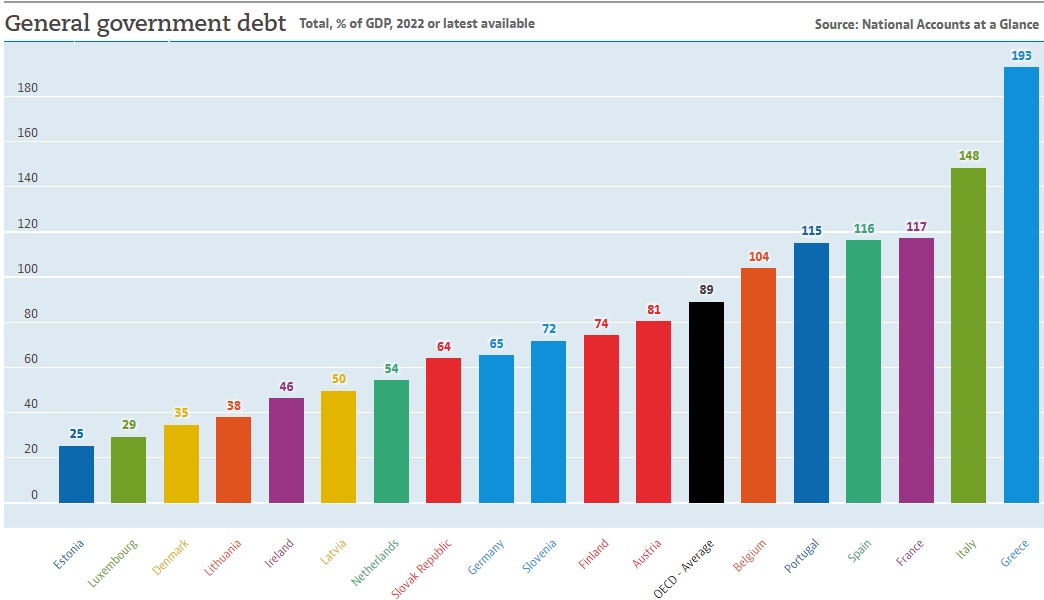

The Eurozone’s moment of truth has arrived with the coronavirus pandemic. …a supply side-shock of unprecedented size to Europe in general and to a highly indebted Italy in particular. Indeed, Italy, the Eurozone’s third-largest member country, is now at the epicenter of the pandemic and is being subject to an economic shock of biblical proportions. …That is all too likely to cause the country’s public debt to skyrocket to over 160 percent of GDP by year-end. It is also likely to put enormous strain on the country’s rickety banking system…it would seem to be only a matter of time before markets…became increasingly reluctant to buy Italian government bonds for fear of an eventual default. They would also…chose to move their deposits out of the Italian banks to safer havens abroad. …we should brace ourselves for an Italian exit from the euro that would almost certainly roil the world’s financial markets.

and is being subject to an economic shock of biblical proportions. …That is all too likely to cause the country’s public debt to skyrocket to over 160 percent of GDP by year-end. It is also likely to put enormous strain on the country’s rickety banking system…it would seem to be only a matter of time before markets…became increasingly reluctant to buy Italian government bonds for fear of an eventual default. They would also…chose to move their deposits out of the Italian banks to safer havens abroad. …we should brace ourselves for an Italian exit from the euro that would almost certainly roil the world’s financial markets.

None of this should be a surprise. Italy is a fiscal mess and I’ve been making that point with tiresome regularity.

The coronavirus and the concomitant economic shutdown are merely a final (and very big) straw on the camel’s back.

So is Italy going to default? And maybe crash out of the euro? Or, alternatively, actually impose some long-overdue spending restraint?

Well, why make any tough decision if there’s a potential new source of money – i.e., cash from taxpayers in Germany, Finland, Austria, the Netherlands, Sweden, and other EU nations in Northern Europe.

Needless to say, that’s a very controversial concept. British newspapers have been writing about this issue.

Here are some passages from a report in the left-leaning Guardian.

The European Union has weathered the storms of eurozone bailouts, the migration crisis and Brexit, but some fear coronavirus could be even more destructive. …Jacques Delors, the former European commission president who helped build the modern EU,  broke his silence last weekend to warn that lack of solidarity posed “a mortal danger to the European Union”. …The pandemic has reopened the wounds of the eurozone crisis, resurrecting stereotypes about “profligate” southern Europeans and “hard-hearted” northerners. …The Dutch finance minister, Wopke Hoekstra,…infuriat[ed] his neighbours by asking why other governments didn’t have fiscal buffers to deal with the financial shock of the coronavirus. His comments were described as “repugnant”, “small-minded” and “a threat to the EU’s future” by Portugal’s prime minister, António Costa.

broke his silence last weekend to warn that lack of solidarity posed “a mortal danger to the European Union”. …The pandemic has reopened the wounds of the eurozone crisis, resurrecting stereotypes about “profligate” southern Europeans and “hard-hearted” northerners. …The Dutch finance minister, Wopke Hoekstra,…infuriat[ed] his neighbours by asking why other governments didn’t have fiscal buffers to deal with the financial shock of the coronavirus. His comments were described as “repugnant”, “small-minded” and “a threat to the EU’s future” by Portugal’s prime minister, António Costa.

Here are excerpts from a piece in the right-leaning Telegraph.

Italian politicians took out a full-page advertisement in one of Germany’s most prestigious newspapers…, urging parsimonious northern Europe to do more to help the south… They urged Berlin to drop its opposition to a proposed EU scheme to issue  so-called “coronabonds” to raise funds to fight the crisis. And they accused the Netherlands, which has led opposition to the scheme, of operating as a tax haven and diverting revenue from other member states. …Several EU members – led by France, Italy, Spain and Belgium – have called for EU-wide “coronabonds” to help poorer member states borrow as they struggle with the economic impact of the crisis. But a rival faction of northern members, led by the Netherlands, Finland, Austria and Germany, has opposed what it sees as an attempt to saddle the countries with the debts of their more feckless neighbours.

so-called “coronabonds” to raise funds to fight the crisis. And they accused the Netherlands, which has led opposition to the scheme, of operating as a tax haven and diverting revenue from other member states. …Several EU members – led by France, Italy, Spain and Belgium – have called for EU-wide “coronabonds” to help poorer member states borrow as they struggle with the economic impact of the crisis. But a rival faction of northern members, led by the Netherlands, Finland, Austria and Germany, has opposed what it sees as an attempt to saddle the countries with the debts of their more feckless neighbours.

An article in the Express highlighted divisions between Portugal and the Netherlands.

Portugal’s Prime Minister Antonio Costa has stunned fellow EU leaders after raising the idea…that the Netherlands could be kicked out of the European Union… The Netherlands held up the talks after blocking demands from Italy, Spain and France for so-called ‘corona-bonds’ where the EU would issue joint shared debt to help finance a recovery. …The Portuguese leader said: “If under these conditions it’s not possible for Europe to ensure a common response to this challenge, this is a sign of great concern for those who believe in Europe.” Mr Costa went on to question whether “there is anyone who wants to be left out” of the EU or eurozone. He added: “Naturally, I’m referring to the Netherlands. “There is at least one country in the euro zone that resists understanding that sharing a common currency implies sharing a common effort.”

where the EU would issue joint shared debt to help finance a recovery. …The Portuguese leader said: “If under these conditions it’s not possible for Europe to ensure a common response to this challenge, this is a sign of great concern for those who believe in Europe.” Mr Costa went on to question whether “there is anyone who wants to be left out” of the EU or eurozone. He added: “Naturally, I’m referring to the Netherlands. “There is at least one country in the euro zone that resists understanding that sharing a common currency implies sharing a common effort.”

The rest of this column is going to explain why it’s a very bad idea to have intra-EU redistribution and bailouts.

But I first want to debunk the claim from the Portuguese Prime Minister that a common currency requires a common fiscal policy.

Indeed, he’s not the only one to make this mistake. In a column for the U.K.-based Times, Iain Martin also asserts that a common currency somehow necessitates cross-country redistribution.

European finance ministers and leaders have spent the week arguing over desperate pleas from countries such as Italy…who want the European Central Bank and the EU to underpin common debt that will cover the epic bills being faced by national governments.  …The fiscally conservative northern nations see no reason why they should take on the “pooled” debt of weaker southern European economies. …The core problem is what it has always been: the elementary design flaw of the euro. Currency blocs that work depend on that notion of common endeavour and “pooling” debt and risk, and ideally must function as one political organisation. …the euro needed an institutional structure that would operate roughly as the United States does. …This escalating economic emergency is a tragedy…a currency and monetary and fiscal construction that is not capable of swiftly transferring resources to the weak.

…The fiscally conservative northern nations see no reason why they should take on the “pooled” debt of weaker southern European economies. …The core problem is what it has always been: the elementary design flaw of the euro. Currency blocs that work depend on that notion of common endeavour and “pooling” debt and risk, and ideally must function as one political organisation. …the euro needed an institutional structure that would operate roughly as the United States does. …This escalating economic emergency is a tragedy…a currency and monetary and fiscal construction that is not capable of swiftly transferring resources to the weak.

Both Costa and Martin are wrong.

Panama does very well using the dollar as its currency, yet there’s obviously no common fiscal policy with the United States. Other nations also have “dollarized” without any adverse impact.

Or consider the fiscal history of the United States. For much of American history, the federal government was trivially small. Most spending happened at the state and local level.

Or consider the fiscal history of the United States. For much of American history, the federal government was trivially small. Most spending happened at the state and local level.

Needless to say, having a common currency in this decentralized system wasn’t a hindrance to U.S. economic development.

With this topic out of the way, let’s now deal with whether the coronavirus crisis should be used as an excuse to open the floodgates for intra-EU redistribution and bailouts.

Politicians from nations on the receiving end obviously approve.

But some Americans also like the idea.

Max Bergmann, a former Obama appointee at the State Department, likes the idea. He argues in the Washington Post for more centralization and more redistribution in the EU.

…this is in fact a fight over the future of Europe. The common European bond proposal hits at the core of what Europe’s union is for. It is an act of unity… A common E.U. bond would take the debt that individual European states accrue to fight this crisis and make it a collective European responsibility.  …Moving ahead with it would entail a sweeping increase in the power of the federal union. …The move by…nine countries for a common E.U. bond was in fact a revolt against Europe’s status quo. It was at its core therefore a revolt against Merkel and the past decade of austerity in Europe. …Merkel is also the architect of a decade of devastating austerity that has caused economic devastation and deprivation… The crisis revealed that Europe’s new currency (the euro) had a design flaw. While the E.U. had a common monetary policy with its own central bank, it lacked a common fiscal policy. …Merkel could have pushed for that. …Merkel lectured southern European countries about profligacy. She turned what was a manageable crisis into a systemic shock to Europe’s economies. …As the coronavirus crisis hit, …Merkel has stuck to her guns.

…Moving ahead with it would entail a sweeping increase in the power of the federal union. …The move by…nine countries for a common E.U. bond was in fact a revolt against Europe’s status quo. It was at its core therefore a revolt against Merkel and the past decade of austerity in Europe. …Merkel is also the architect of a decade of devastating austerity that has caused economic devastation and deprivation… The crisis revealed that Europe’s new currency (the euro) had a design flaw. While the E.U. had a common monetary policy with its own central bank, it lacked a common fiscal policy. …Merkel could have pushed for that. …Merkel lectured southern European countries about profligacy. She turned what was a manageable crisis into a systemic shock to Europe’s economies. …As the coronavirus crisis hit, …Merkel has stuck to her guns.

The New York Times, unsurprisingly, has editorialized for centralization and redistribution.

…the European Union is…an alliance of sovereign countries, not a central government, and Brussels has control only over external trade and competition. For the rest, its executive branch, the European Commission, can only seek cooperation, not order it.  The states that share the euro do not have true fiscal union, under which wealthier parts of the bloc would prop up the poorer. …Europe could do better. Much better. …Italians or Spaniards confronted with death and economic catastrophe…aren’t in a bind due to profligate spending; they’re in the throes of a plague… The question to ask is what’s the point of any union if it cannot find unity when it is needed most…true leadership requires knowing that we’re all in this together and can only conquer it together.

The states that share the euro do not have true fiscal union, under which wealthier parts of the bloc would prop up the poorer. …Europe could do better. Much better. …Italians or Spaniards confronted with death and economic catastrophe…aren’t in a bind due to profligate spending; they’re in the throes of a plague… The question to ask is what’s the point of any union if it cannot find unity when it is needed most…true leadership requires knowing that we’re all in this together and can only conquer it together.

Is this correct? Would it be a good idea to have “a sweeping increase in the power of the federal union”? Would that be “true leadership”?

Gideon Rachman warns in the Financial Times that such policies will cause political fallout.

…northern Europeans will…feel exploited by the south. …The longer-term fears of the northern Europeans are also legitimate. …The northerners are alert to any sign that they are being sucked into permanent, large transfers of cash  to heavily indebted EU partners. They are justifiably concerned that the current anguish is being used to push forward ideas that they have already rejected, many times over. …if political leaders renege on longstanding promises…, they should not be particularly surprised if voters then turn to populist, anti-European parties. …Anti-EU parties have already made strong gains across northern Europe in recent years.

to heavily indebted EU partners. They are justifiably concerned that the current anguish is being used to push forward ideas that they have already rejected, many times over. …if political leaders renege on longstanding promises…, they should not be particularly surprised if voters then turn to populist, anti-European parties. …Anti-EU parties have already made strong gains across northern Europe in recent years.

That’s very sensible political analysis.

But the bigger problem, at least from my perspective, is that a common fiscal policy would be very bad economics.

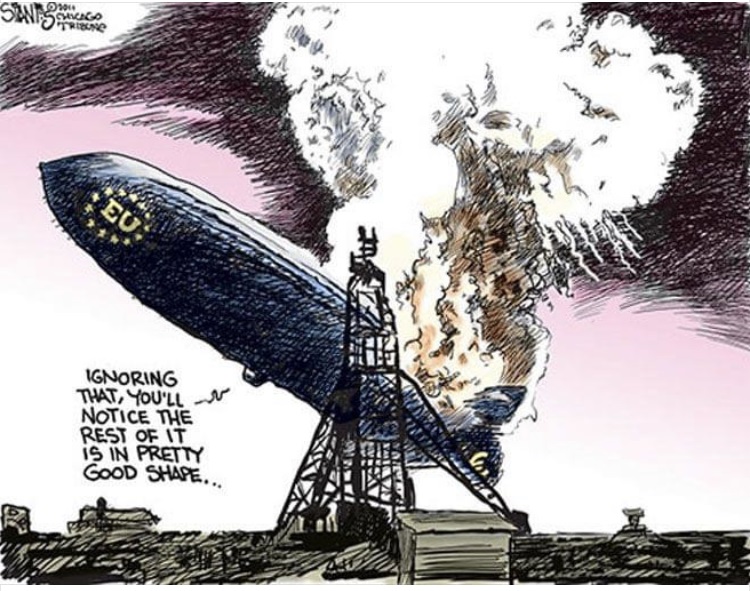

It means more redistribution, with all the unfortunate incentives that creates for both those paying and those receiving (as illustrated by this cartoon).

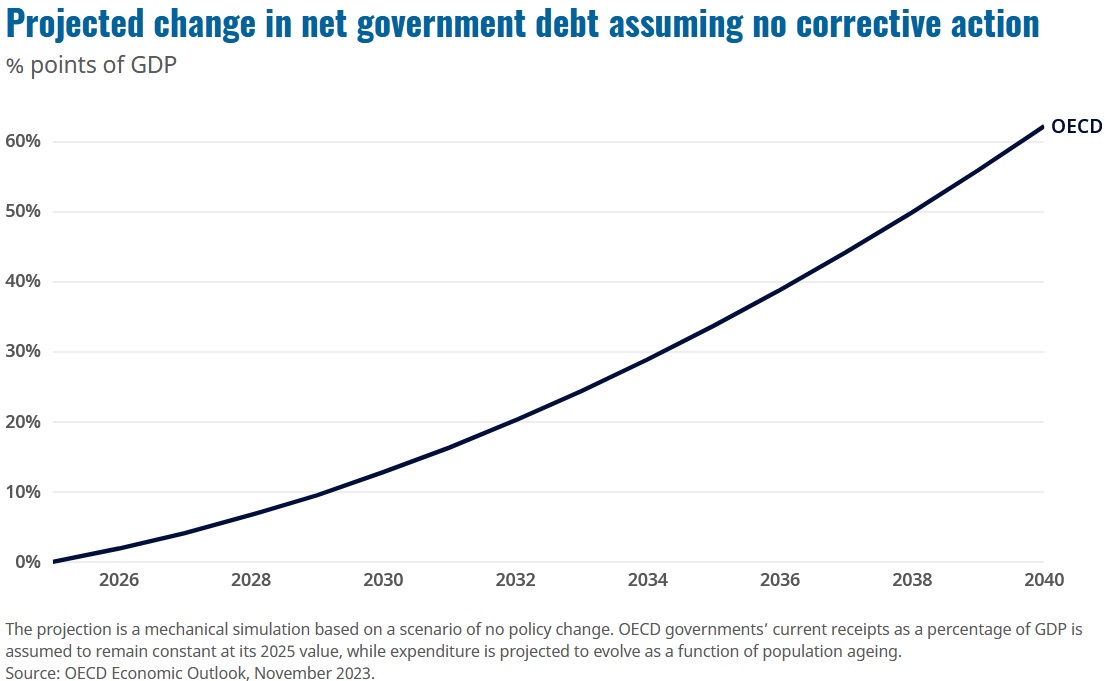

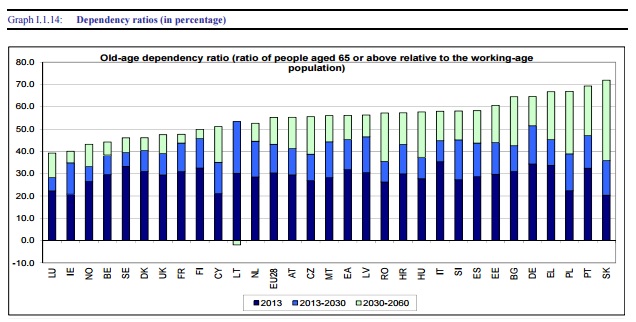

And it means more overall government spending. The “Club Med” countries obviously would spend any money they got (whether from so-called coronabonds, a common-EU budget, or any other mechanism), and there’s no reason to think the nations in Northern Europe would reduce spending as their taxpayers started to underwrite the budgets of other nations.

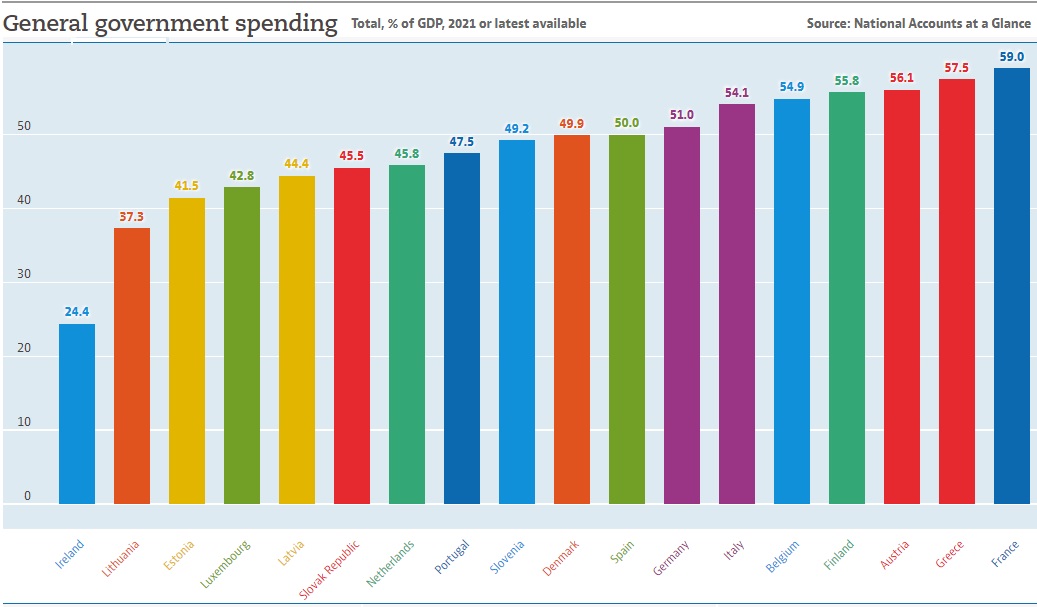

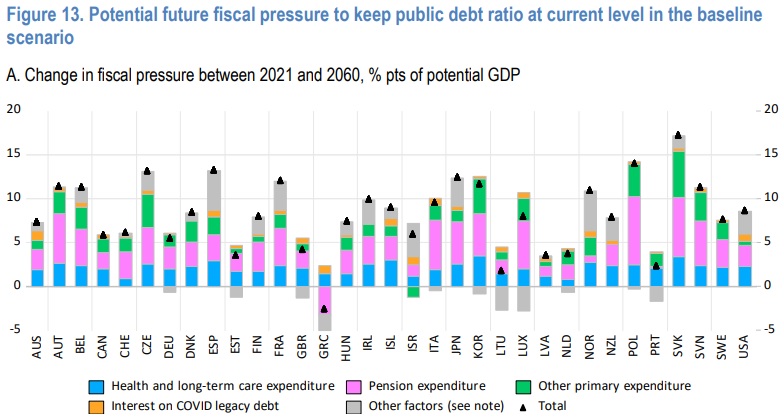

This is a problem since government already is far too large in every EU country. Here’s the most-recent data from the European Commission. If you focus on the left, you’ll see the average fiscal burden in the EU is about 45 percent of GDP (and slightly higher in the subset of eurozone countries).

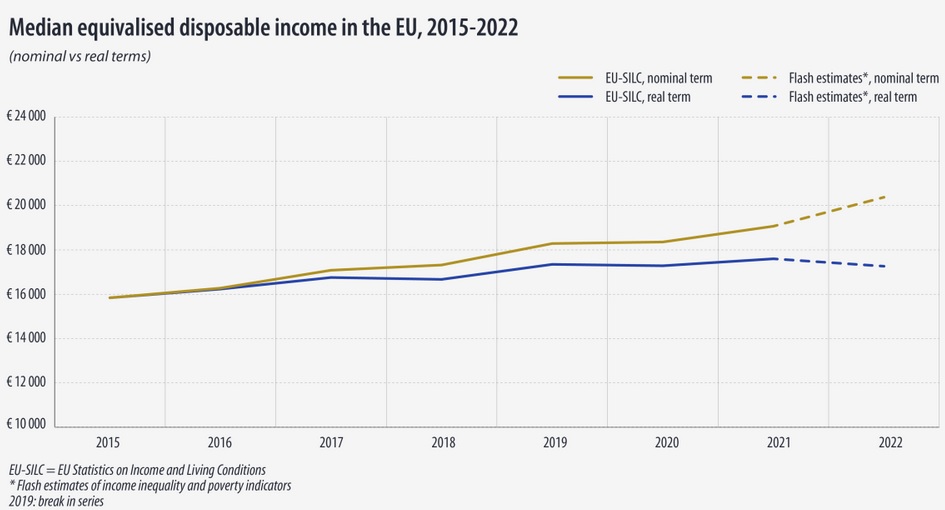

The bottom line is that countries such as Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal are in trouble because their governments have been spending too much.

Sadly, I fear it is just a matter of time before Article 125 is somehow sidelined and the profligacy of those “Club Med” nations is rewarded.

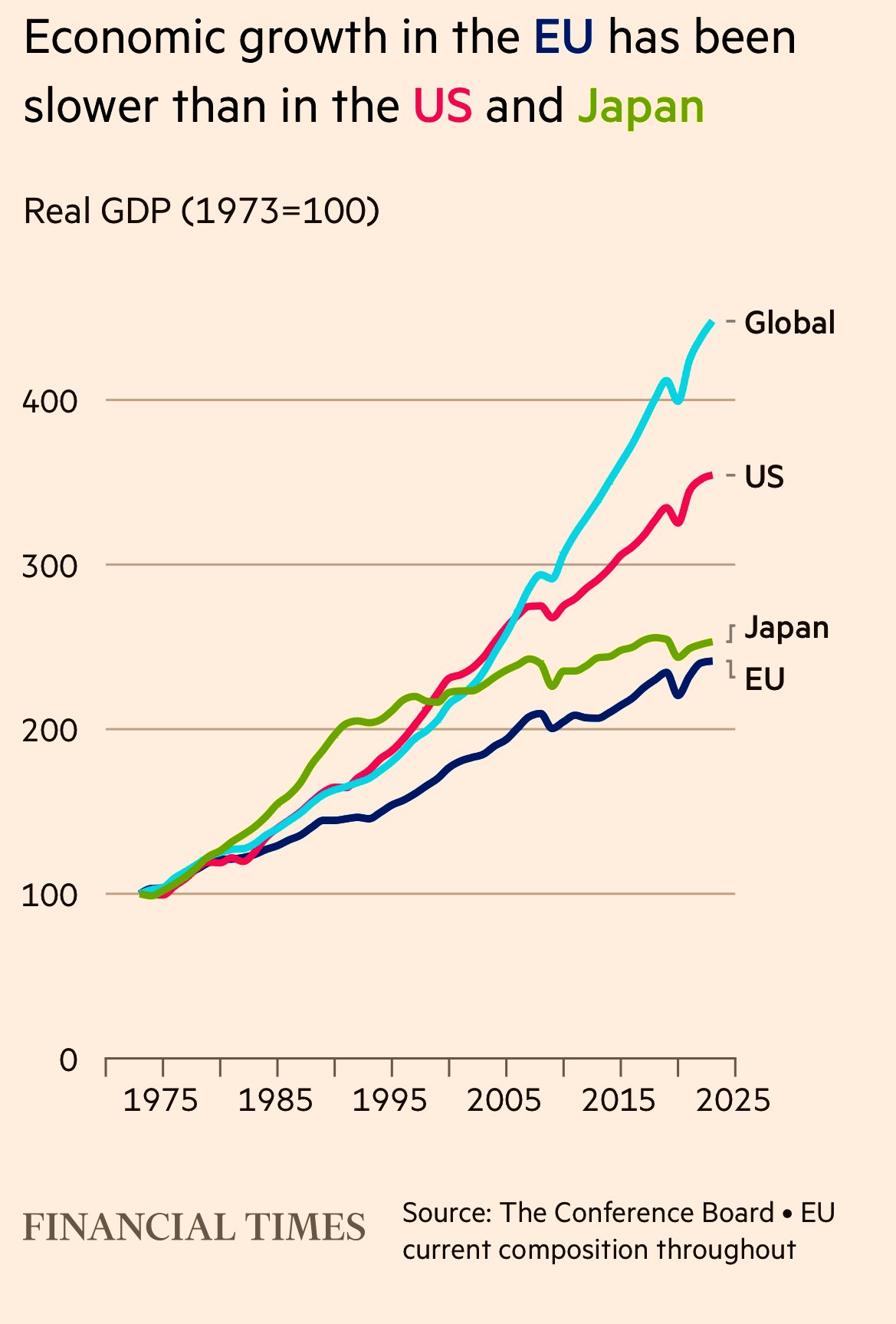

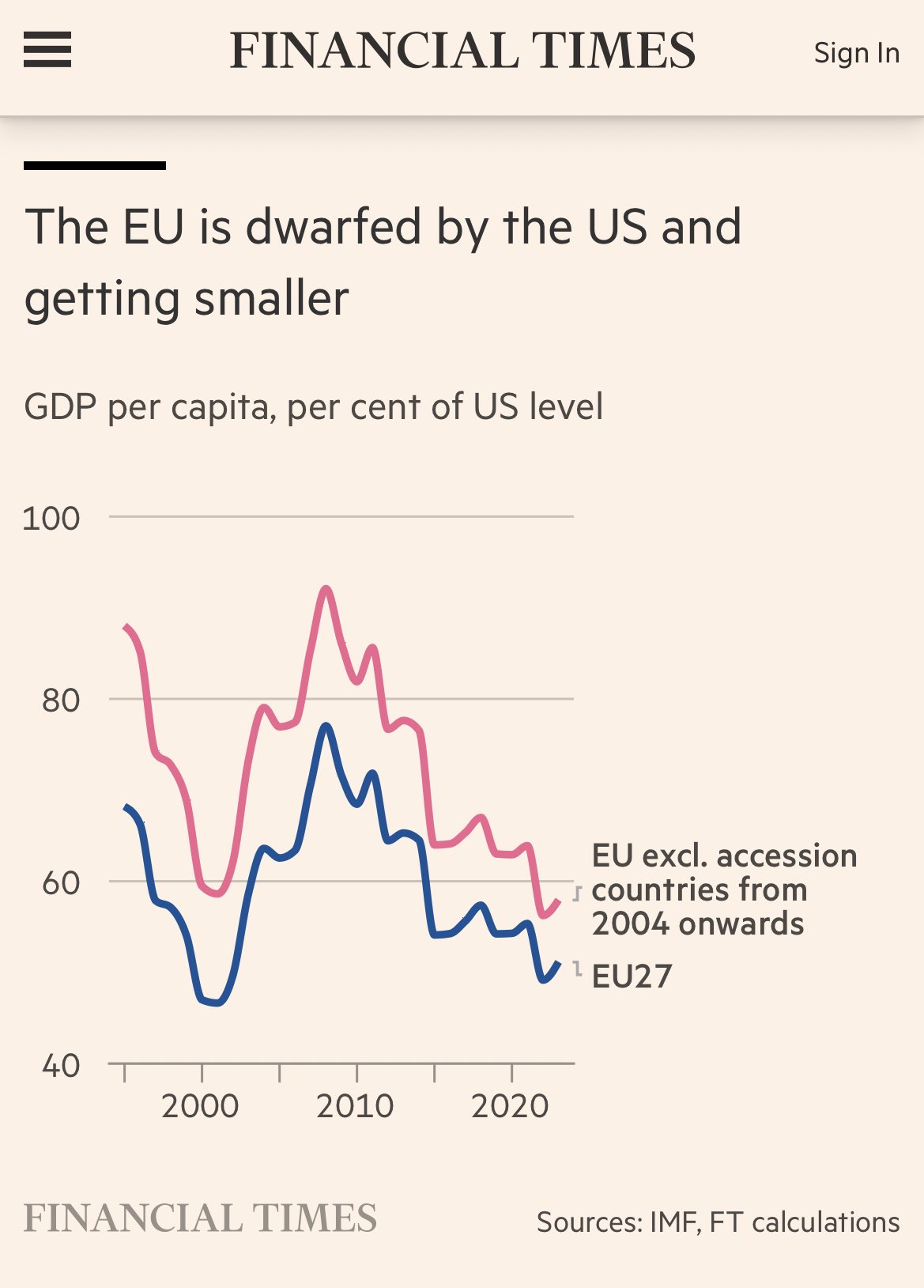

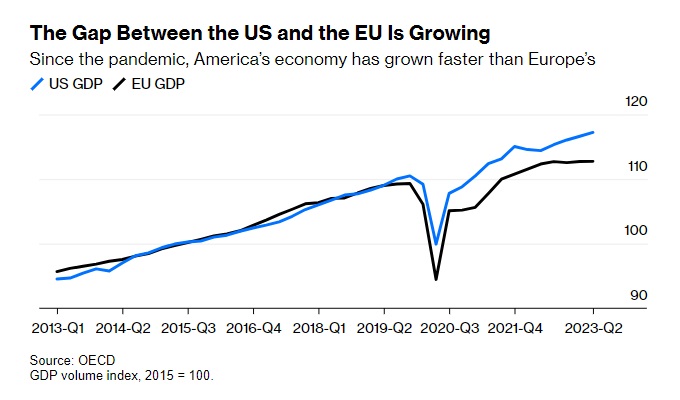

And if/when that happens, what’s good about the EU (open trade and the remnants of mutual recognition) definitely will be dwarfed by bad policy (bailouts, transfers, and others form of redistribution).

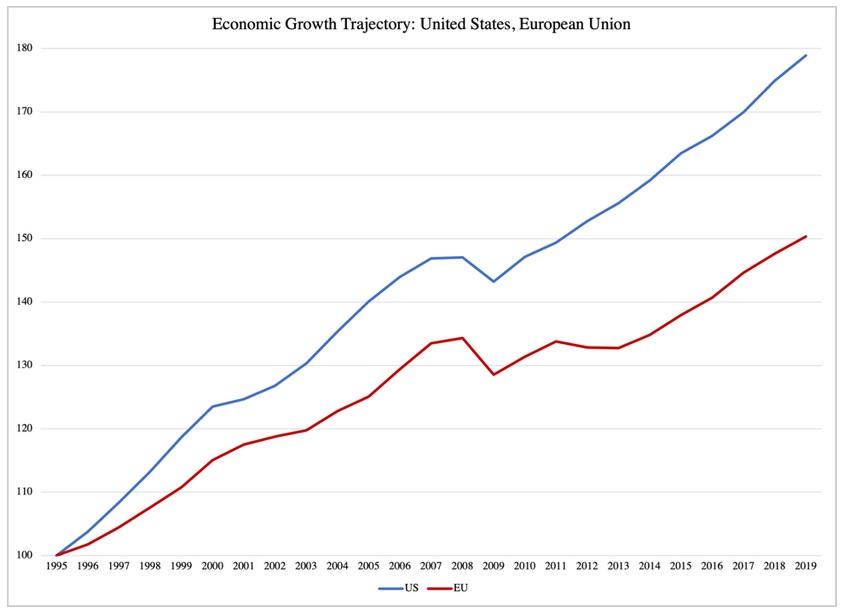

P.S. One of the strongest arguments for Brexit was that the EU inevitably would morph into a transfer union – and thus accelerate the economic decline of Europe. Given what’s now happening, the British were very wise to escape.

Read Full Post »

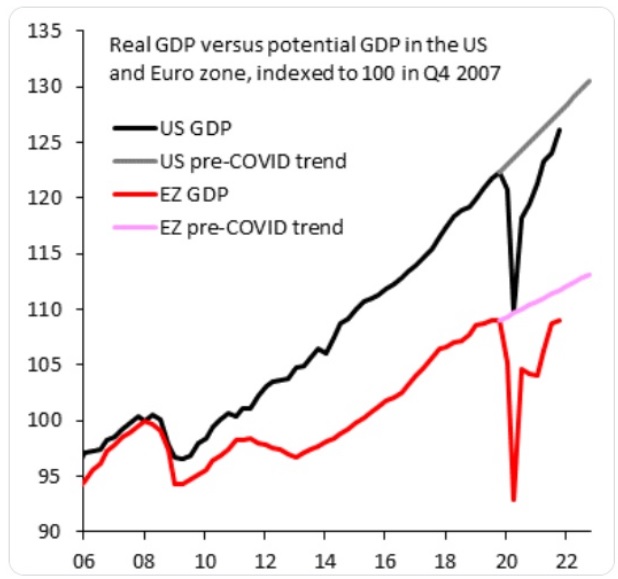

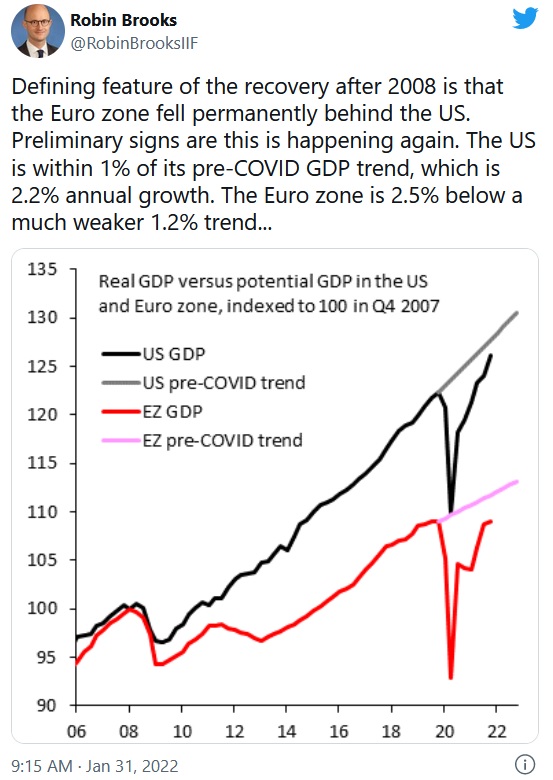

income levels today in countries like Greece and Italy are practically unchanged from where they were some 15 years ago. Meanwhile, public-debt levels in the euro zone’s economic periphery have risen to record highs. …there is every reason to think that economic divergences will be exacerbated. That will raise new questions about the euro’s survivability once the European Central Bank (ECB) finally ends its bond-buying activities.