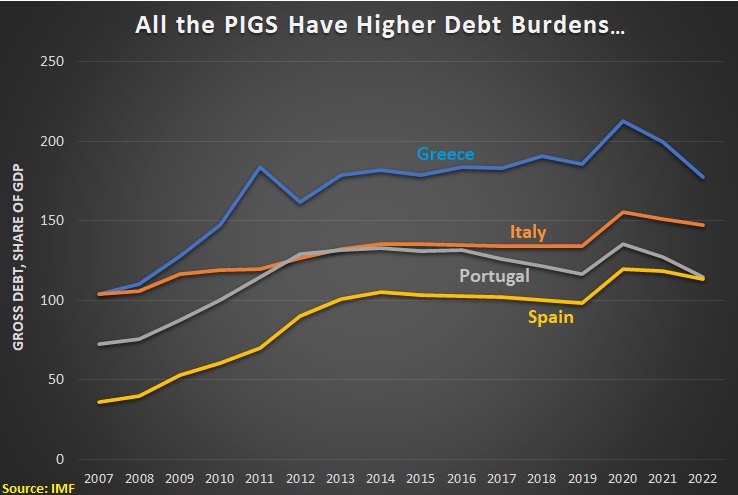

I wrote a two-part series (here and here) in 2022 predicting that Italy was at risk of suffering a fiscal crisis.

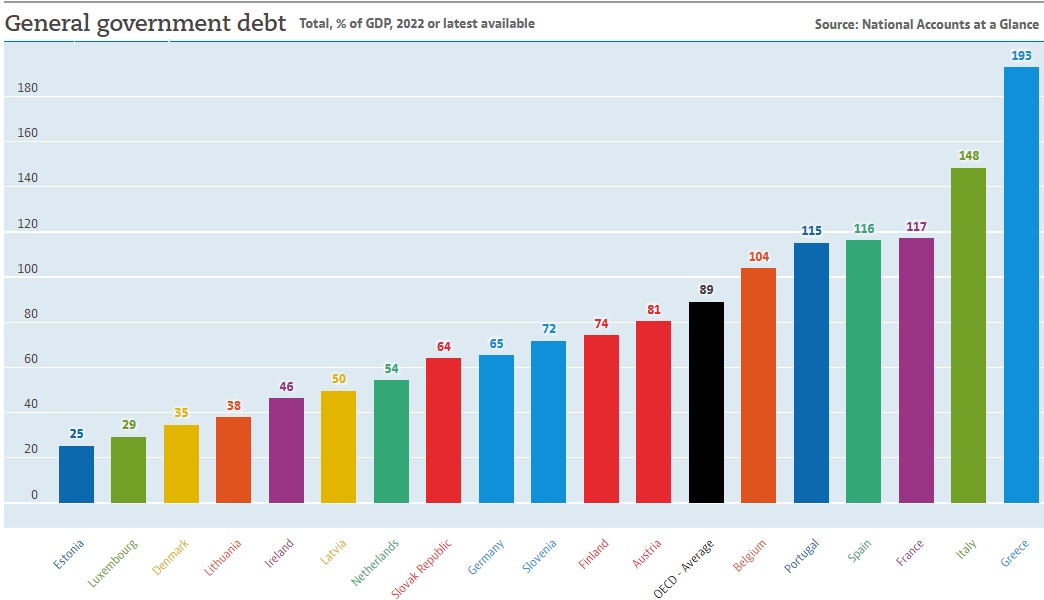

If and when it occurs, it will be because investors decide that Italy’s government might default (i.e., be unable to make payments on its debt). Interest rates would spike, financial markets would get shaky, banks would be a risk, and there would be a lot of pressure for a Greek-style bailout.

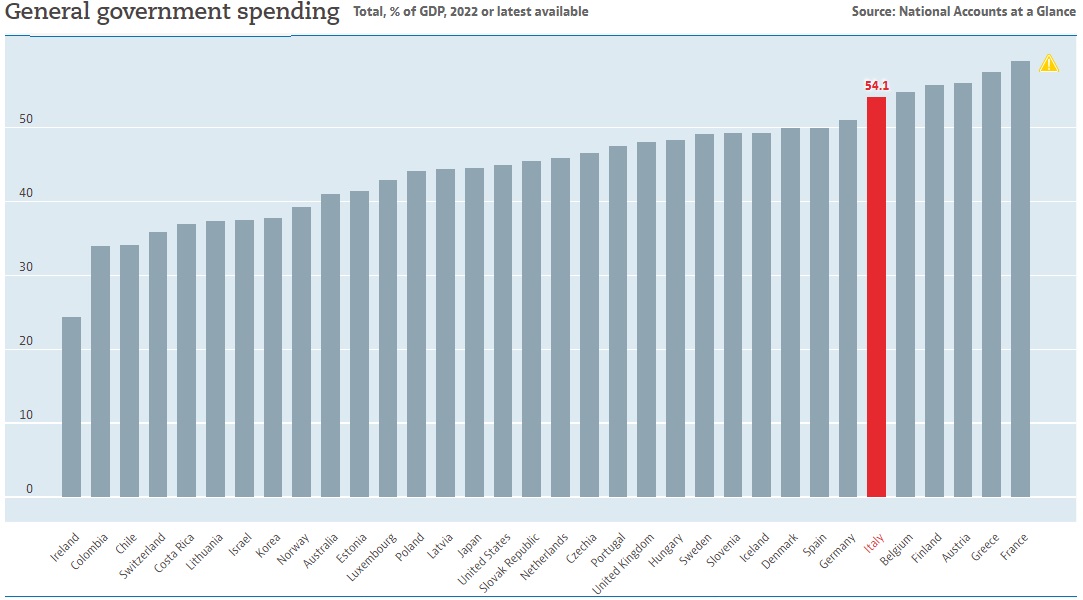

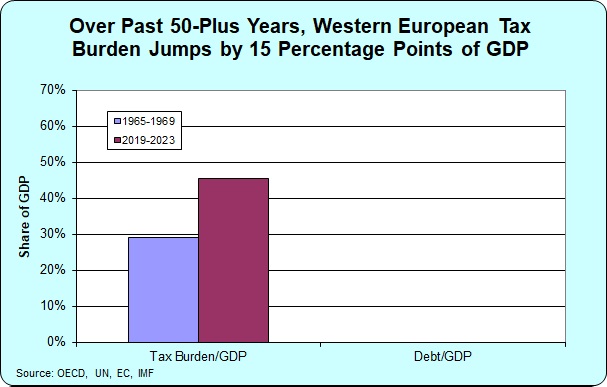

Should that happen, my role will be to point out that the real problem is that the burden of government spending in Italy is excessive (same message I delivered a dozen years ago).

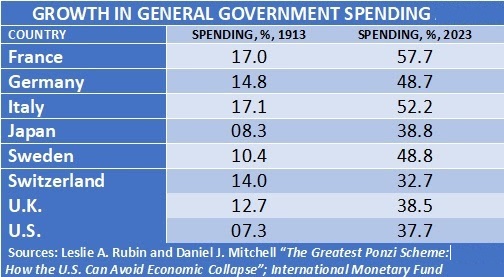

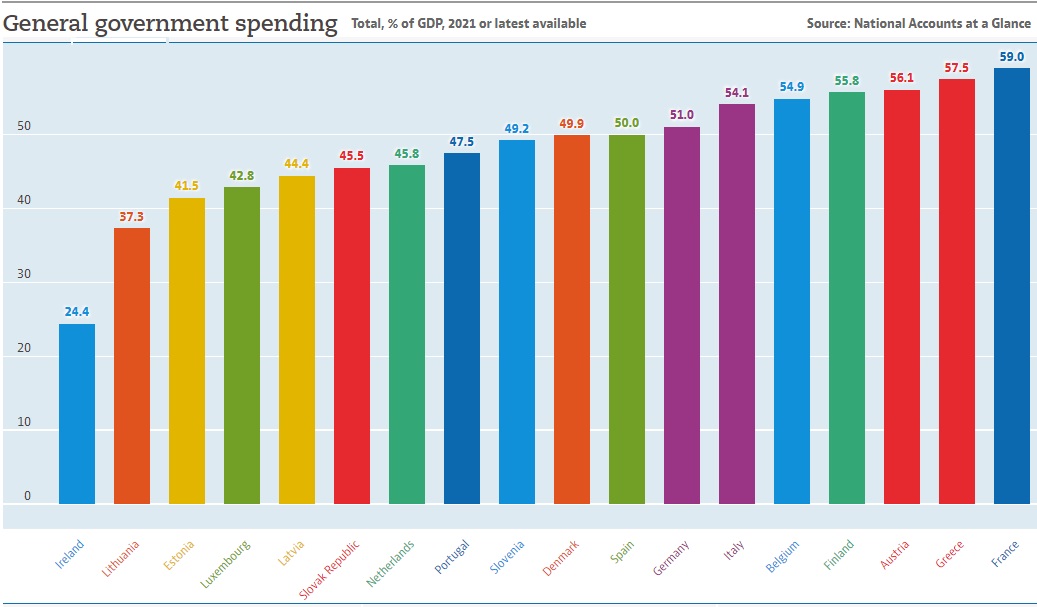

As shown by OECD data, it’s one of the most profligate nations in Europe.

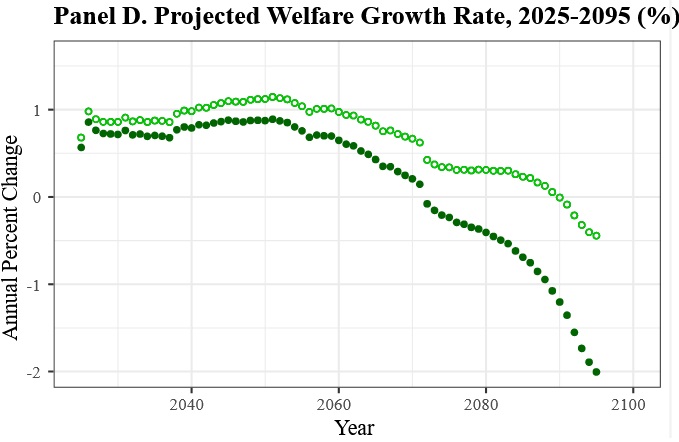

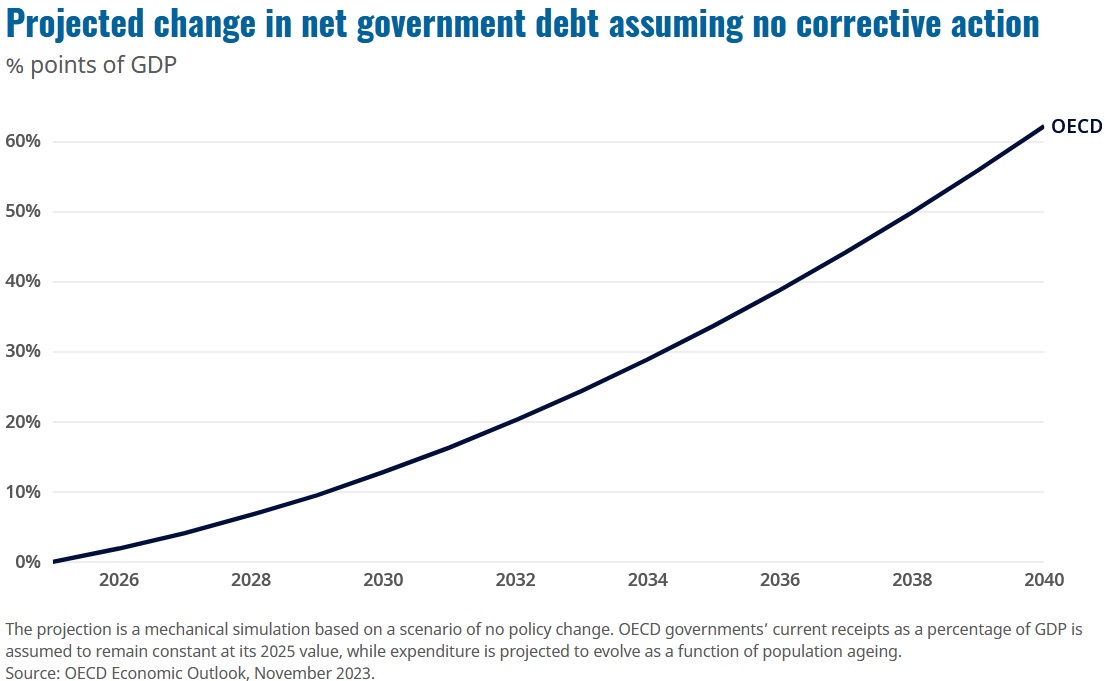

And I suppose it’s worth mentioning that Italy’s demographic outlook is very grim, thus increasing medium- and long-run fiscal risks.

That’s the macro outlook.

Now let’s look at a specific example of why Italy is a fiscal mess. The Economist recently reported on a government giveaway that has become a nightmare.

…a home-improvements subsidy…has turned into the fiscal equivalent of King Kong: a monster running amok, wreaking havoc… Mr Giorgetti revealed that claims of the subsidy, known as the “superbonus”, made in the four years that the scheme has been running, together with claims of another that offsets the cost of renovating façades, would eventually drain the treasury of €219bn ($233bn). That is almost 10% of Italy’s GDP last year. …a left-populist coalition…introduced the superbonus in 2020… The idea was to stimulate the stricken economy… The government offered to pay homeowners 110% of the price of energy-saving renovations.

…The cash was not to be reimbursed directly, but in the form of tax credits that could be sold on. …the superbonus has proved wildly popular. That should not have been a surprise: what is not to like about being repaid more than you have spent? Or not spent: since the tax credits are tradeable, many homeowners simply passed them on to their builders without having to part with a euro. A second reason is outright fraud. Last August Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister, said that contracts falsified to claim the subsidies constituted the biggest-ever rip-off of the Italian state. That was when they amounted to a mere €12bn; since then, the figure has risen to €16bn. A third problem is overpricing. Because the superbonus refund is greater than the outlay, actual or theoretical, it is in the interests of both the builder and the homeowner to inflate the cost of the work.

At the risk of understatement, this is one of the dumbest spending programs I’ve ever read about.

To put this in an American context, it’s sort of like adding together the fraud of the Trump-Biden pandemic spending, the perverse incentives created by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the third-party payer problem caused by government in the health sector.