In addition to being a contest over expanding the burden of government spending, the Democratic primary also is a contest  to see who wants the biggest tax increases.

to see who wants the biggest tax increases.

Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren have made class-warfare taxation an integral part of their campaigns, but even some of the supposedly reasonable Democrats are pushing big increases in tax rates.

James Pethokoukis of the American Enterprise Institute opines about the anti-growth effect of these proposed tax hikes, particularly with regard to entrepreneurship and successful new firms.

The Democratic presidential candidates have plenty of ideas about taxes. Wealth taxes. Wall Street taxes. Inequality taxes. And probably more to come. So lots of creative thinking about wealth redistribution. Wealth creation? Not so much. …one way to look at boosting GDP growth  is thinking about specific policies to boost labor force and productivity growth. But there’s another way of approaching the issue: How many fast-growing growing new firms would need to be generated each year to lift the economy-wide growth rate each year by one percent? …a rough calculation by analyst Robert Litan figures there about 15 billion-dollar (in sales) companies formed every year. But what if the American entrepreneurial ecosystem were so vibrant that it produced 60 such companies annually? …The big point here is that the American private sector is key to growth. No other large economy is as proficient as the US in creating high-impact startups. But it doesn’t appear that the Democratic enthusiasm for big and bold tax plans is matched by concern about unwanted trade-offs.

is thinking about specific policies to boost labor force and productivity growth. But there’s another way of approaching the issue: How many fast-growing growing new firms would need to be generated each year to lift the economy-wide growth rate each year by one percent? …a rough calculation by analyst Robert Litan figures there about 15 billion-dollar (in sales) companies formed every year. But what if the American entrepreneurial ecosystem were so vibrant that it produced 60 such companies annually? …The big point here is that the American private sector is key to growth. No other large economy is as proficient as the US in creating high-impact startups. But it doesn’t appear that the Democratic enthusiasm for big and bold tax plans is matched by concern about unwanted trade-offs.

If you want a substantive economic critique of class-warfare tax policy, Alan Reynolds has a must-read article on the topic.

He starts by explaining why it’s important to measure how sensitive taxpayers are (the “elasticity of taxable income”) to changes in tax rates.

Elasticity of taxable income estimates are simply a relatively new summary statistic used to illustrate observed behavioral responses to past variations in marginal tax rates. They do so by examining what happened  to the amount of income reported on individual tax returns, in total and at different levels of income, before and after major tax changes. …For example, if a reduced marginal tax rate produces a substantial increase in the amount of taxable income reported to the IRS, the elasticity of taxable income is high. If not, the elasticity is low. ETI incorporates effects of tax avoidance as well as effects on incentives for productive activity such as work effort, research, new business start-ups, and investment in physical and human capital.

to the amount of income reported on individual tax returns, in total and at different levels of income, before and after major tax changes. …For example, if a reduced marginal tax rate produces a substantial increase in the amount of taxable income reported to the IRS, the elasticity of taxable income is high. If not, the elasticity is low. ETI incorporates effects of tax avoidance as well as effects on incentives for productive activity such as work effort, research, new business start-ups, and investment in physical and human capital.

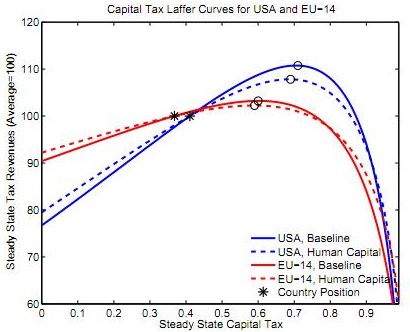

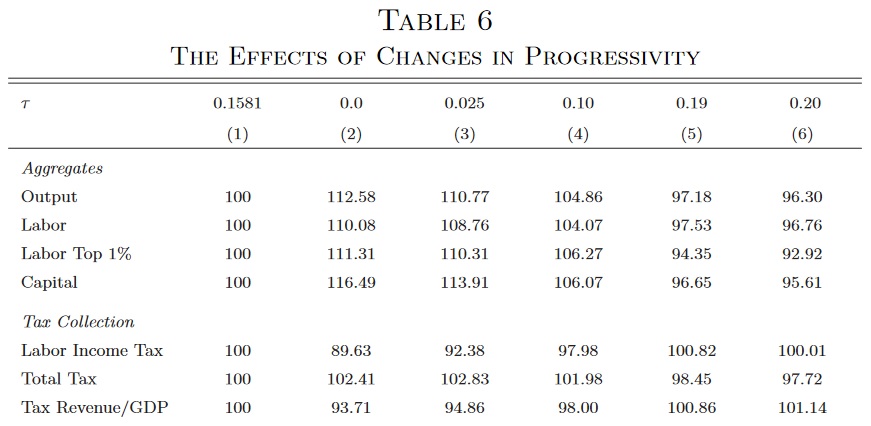

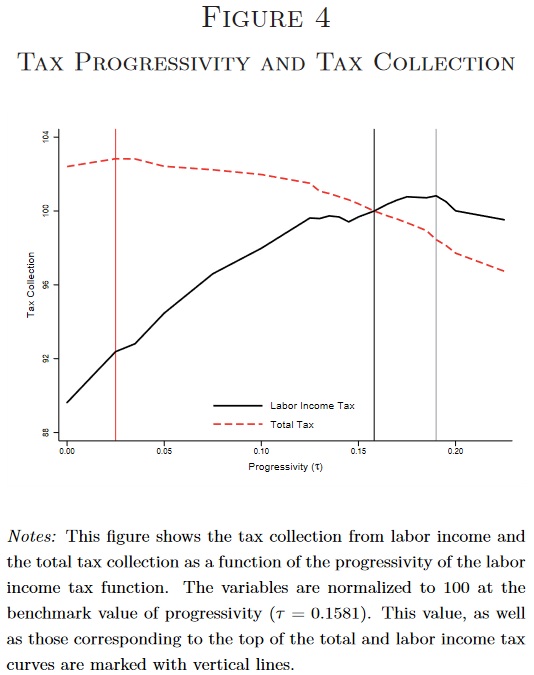

Alan then looks at some of the ETI estimates and what they imply for tax rates, though he notes that the revenue-maximizing rate is not the optimal rate.

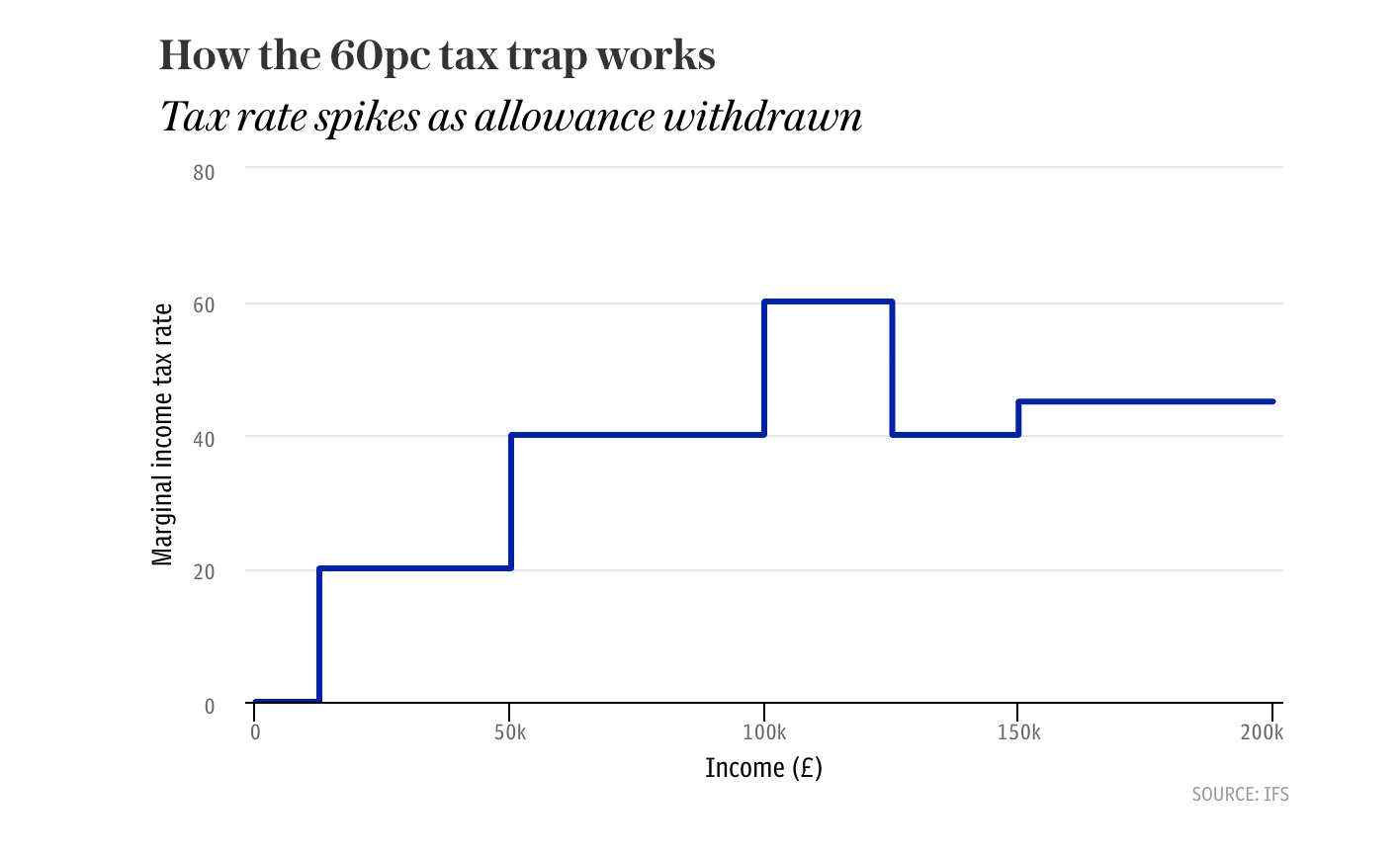

Diamond and Saez claim that, if the relevant ETI is 0.25, then the revenue-maximizing top tax rate is 73 percent. Such estimates, however, do not refer to the top federal income tax rate, …but to the combined marginal rate on income, payrolls, and sales at the federal, state, and local level. …with empirically credible changes in parameters, the Diamond-Saez formula can more easily be used to show that top U.S. federal, state, and local tax rates are already too high rather than too low. By also incorporating dynamic effects — such as incentives to invest in human capital and new ideas — more recent models estimate that the long-term revenue-maximizing top tax rate is between 22 and 49 percent… Elasticity of taxable, or perhaps gross income…can be “a sufficient statistic to approximate the deadweight loss” from tax disincentives and distortions. Although recent studies define revenue-maximization as “optimal,” Goolsbee…rightly emphasizes, “The fact that efficiency costs rise with the square of the tax rate are likely to make the optimal rate well below the revenue-maximizing rate.”

These excerpts only scratch the surface.

Alan’s article extensively discusses how high-income taxpayers are especially sensitive to high tax rates, in part because they have considerable control over the timing, level, and composition of their income.

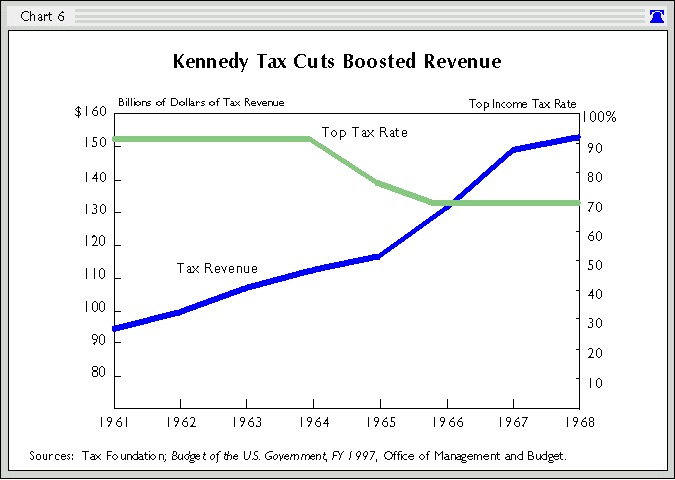

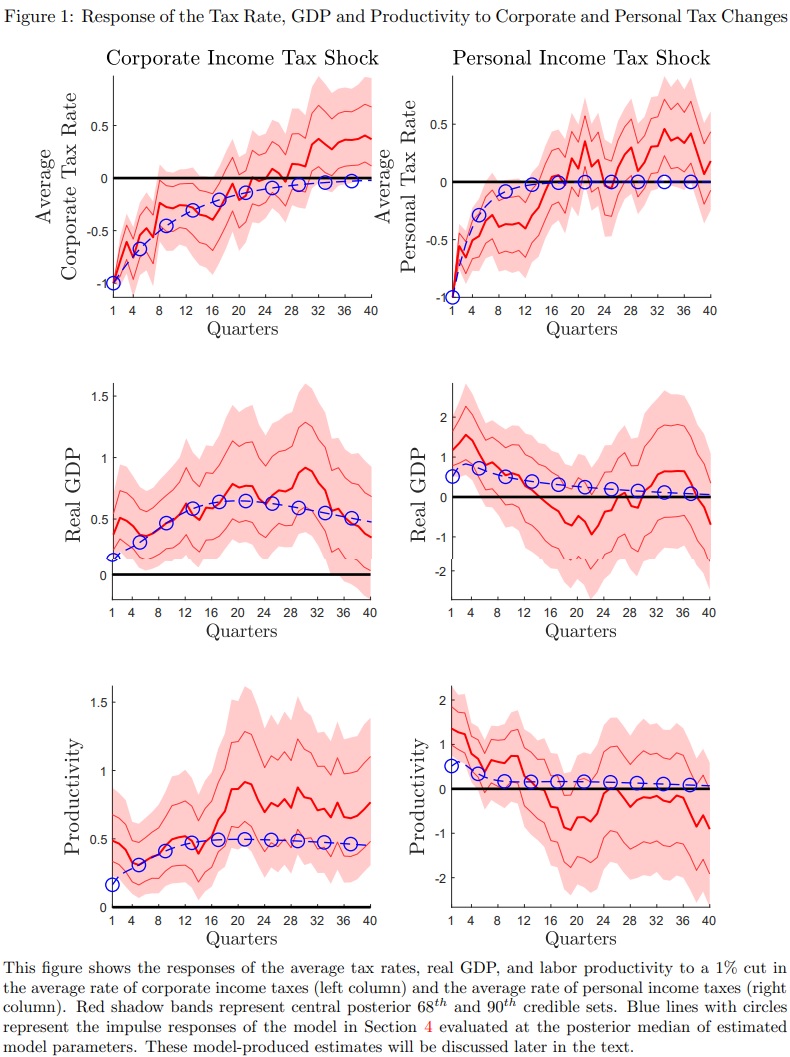

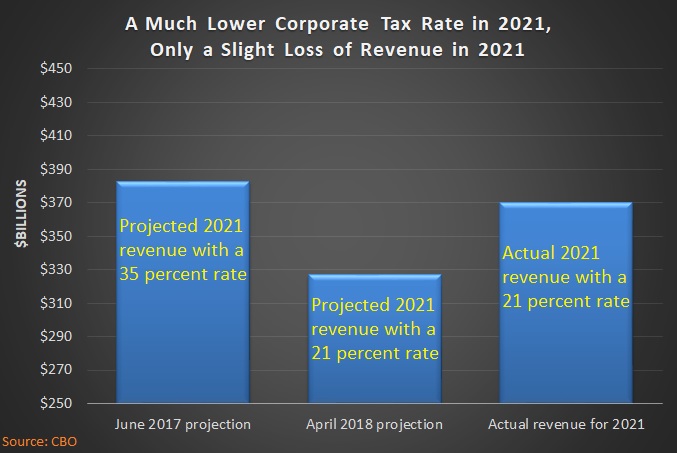

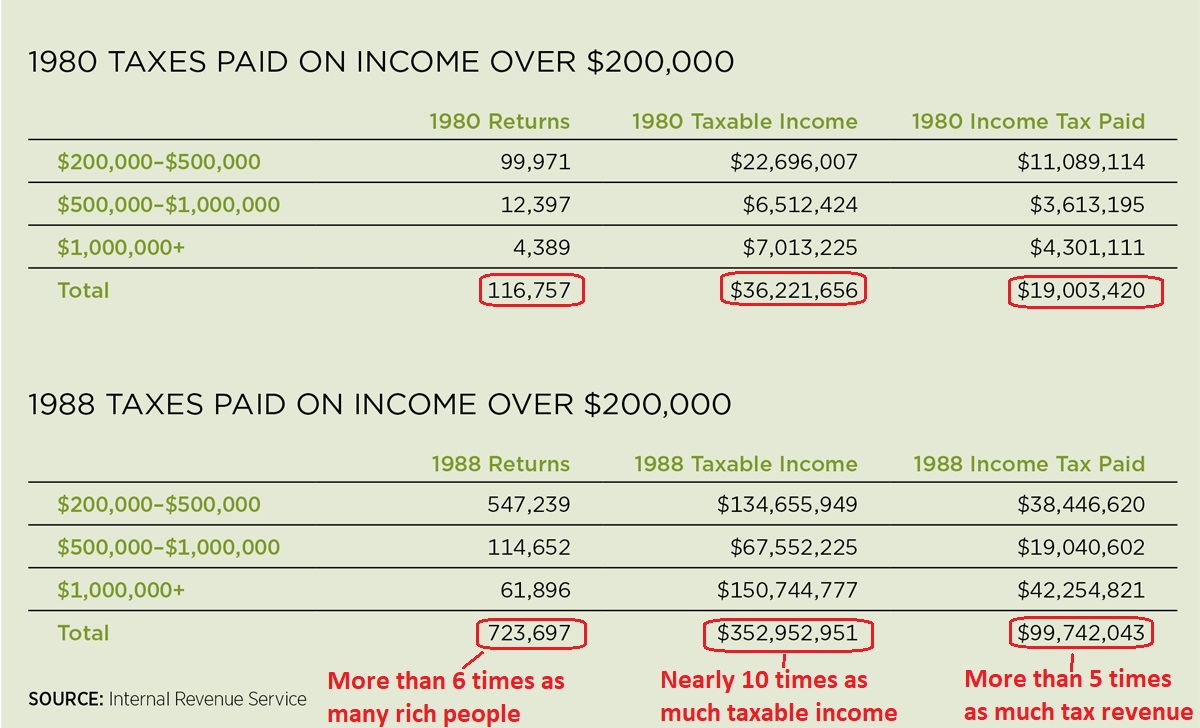

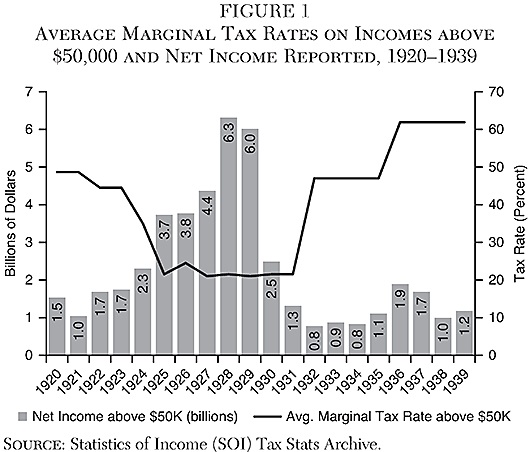

He also reviews the empirical evidence from major shifts in tax rates last century.

All told, his article is a devastating take-down of the left-of-center economists who have tried to justify extortionary tax rates. Simply stated, high tax rates hinder the economy, create deadweight loss, and don’t produce revenue windfalls.

That being said, I wonder whether his article will have any impact. As Kevin Williamson points out is a column for National Review, the left isn’t primarily motivated by a desire for more tax money.

Perhaps the strangest utterance of Barack Obama’s career in public office…was his 2008 claim that raising taxes on the wealthy is a moral imperative, even if the tax increase in question ended up reducing overall federal revenue. Which is to say, Obama argued that it did not matter whether a tax increase hurt the Treasury, so long as it also hurt, at least in theory and on paper, certain wealthy people. …ideally, you want a tax system with low transaction costs (meaning a low cost of compliance) and one that doesn’t distort a lot of economic activity. You want to get enough money to fund your government programs with as little disruption to life as possible. …Punitive taxes aren’t about the taxes — they’re about the punishment. That taxation should have been converted from a technical question into a moral crusade speaks to the basic failure of the progressive enterprise in the United States…the progressive demand for a Scandinavian welfare state at no cost to anybody they care about…ends up being a very difficult equation to balance, probably an impossible one. And when the numbers don’t work, there’s always cheap moralistic histrionics.

…ideally, you want a tax system with low transaction costs (meaning a low cost of compliance) and one that doesn’t distort a lot of economic activity. You want to get enough money to fund your government programs with as little disruption to life as possible. …Punitive taxes aren’t about the taxes — they’re about the punishment. That taxation should have been converted from a technical question into a moral crusade speaks to the basic failure of the progressive enterprise in the United States…the progressive demand for a Scandinavian welfare state at no cost to anybody they care about…ends up being a very difficult equation to balance, probably an impossible one. And when the numbers don’t work, there’s always cheap moralistic histrionics.

So what leads our friends on the left to pursue such misguided policies? What drives their support for punitive taxation?

Is is that they’re overflowing with compassion and concern for the poor?

Hardly.

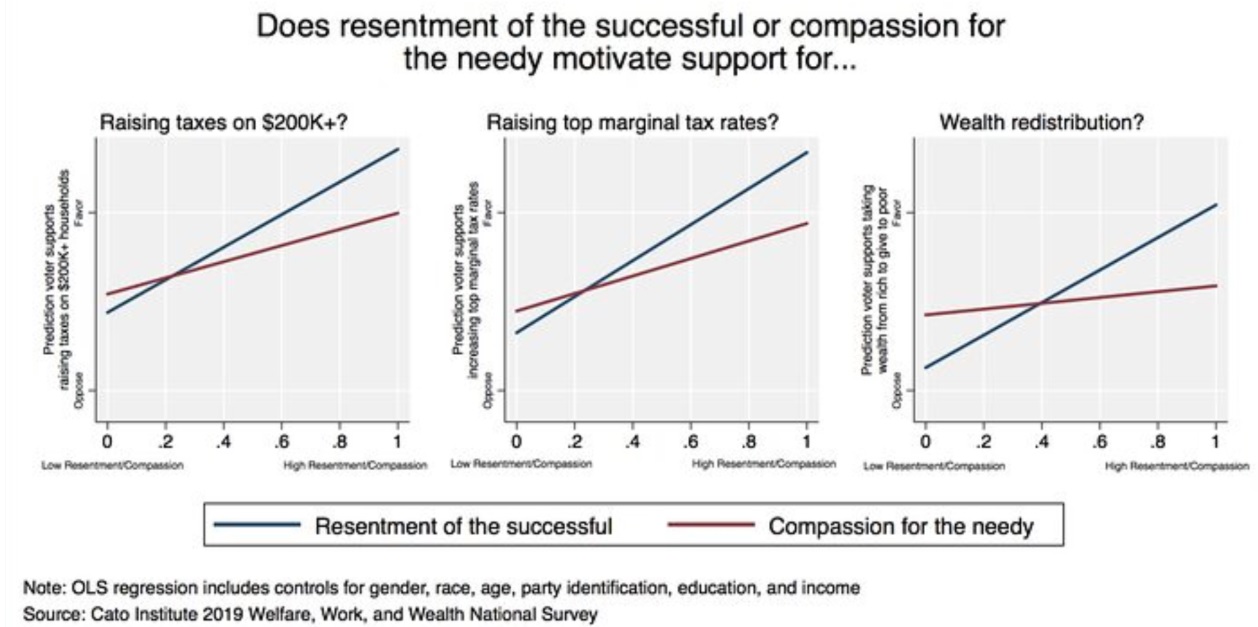

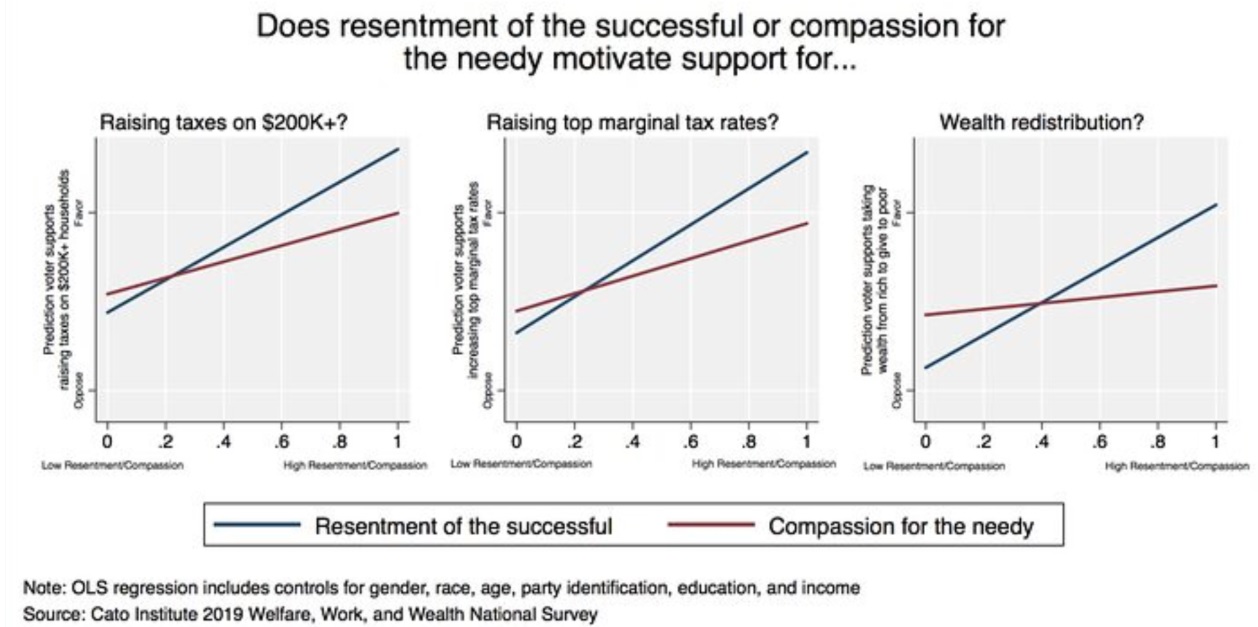

Writing for the Federalist, Emily Ekins shares some in-depth polling data that discovers that envy is the real motive.

Supporters often contend their motivation is compassion for the dispossessed… In a new study, I examine…competing explanations and ask whether envy and resentment of the successful or compassion for the needy better explain support for socialism, raising taxes on the rich, redistribution, and the like. …Statistical tests reveal resentment of the successful has about twice the effect of compassion in predicting support for  increasing top marginal tax rates, wealth redistribution, hostility to capitalism, and believing billionaires should not exist. …people who agree that “very successful people sometimes need to be brought down a peg or two even if they’ve done nothing wrong” were more likely to want to raise taxes on the rich than people who agree that “I suffer from others’ sorrows.” …I ran another series of statistical tests to investigate the motivations behind the following beliefs: 1) It’s immoral for our system to allow the creation of billionaires, 2) billionaires threaten democracy, and 3) the distribution of wealth in the United States is “unjust.” Again, the statistical tests find that resentment against successful people is more influential than compassion in predicting each of these three beliefs. In fact, not only is resentment more impactful, but compassionate people are significantly less likely to agree that it’s immoral for our system to allow people to become billionaires.

increasing top marginal tax rates, wealth redistribution, hostility to capitalism, and believing billionaires should not exist. …people who agree that “very successful people sometimes need to be brought down a peg or two even if they’ve done nothing wrong” were more likely to want to raise taxes on the rich than people who agree that “I suffer from others’ sorrows.” …I ran another series of statistical tests to investigate the motivations behind the following beliefs: 1) It’s immoral for our system to allow the creation of billionaires, 2) billionaires threaten democracy, and 3) the distribution of wealth in the United States is “unjust.” Again, the statistical tests find that resentment against successful people is more influential than compassion in predicting each of these three beliefs. In fact, not only is resentment more impactful, but compassionate people are significantly less likely to agree that it’s immoral for our system to allow people to become billionaires.

Here’s one of her charts, showing that resentment is far and away the biggest driver of support for class-warfare proposals.

These numbers are quite depressing.

They suggest that no amount of factual analysis or hard data will have any effect on the debate.

And there is polling data to back up Emily’s statistical analysis. Heck, some folks on the left openly assert that envy should be the basis for tax policy.

In other words, Deroy Murdock and Margaret Thatcher weren’t creating imaginary enemies.

P.S. If you think Kevin Williamson was somehow mischaracterizing or exaggerating Obama’s spiteful position on tax policy, just watch this video.

Read Full Post »

in America’s economic renaissance?

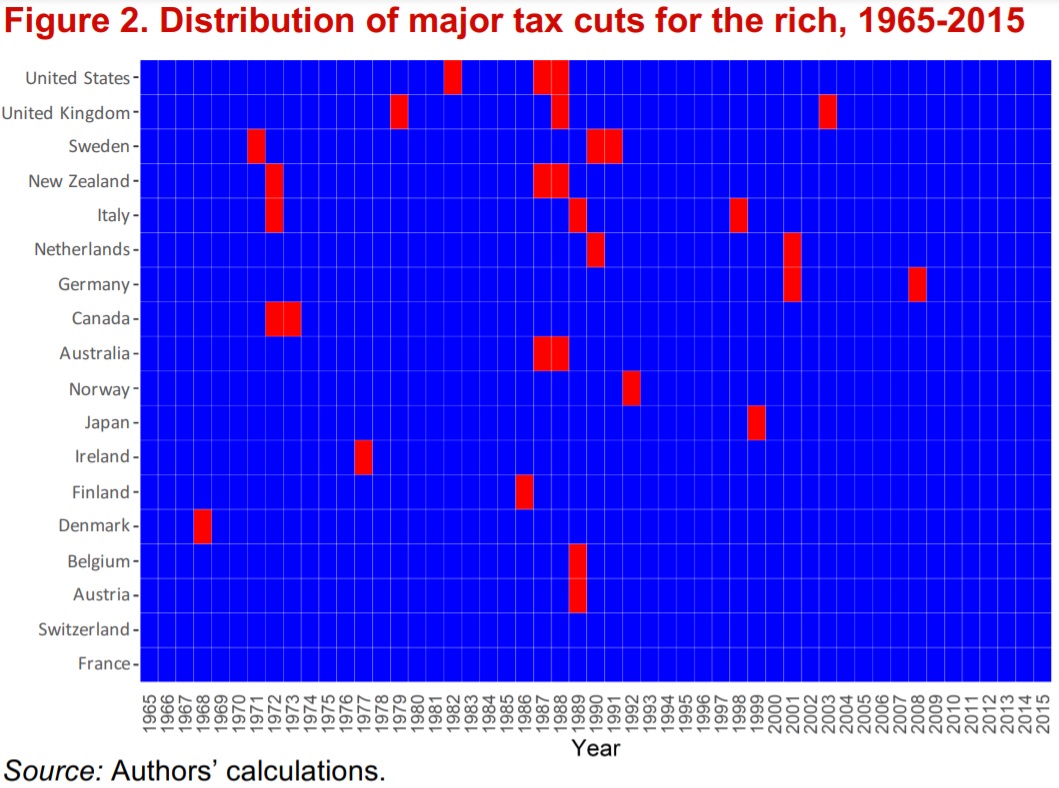

in America’s economic renaissance?It turns out that “per capita gross domestic product and unemployment rates were nearly identical after five years in countries that slashed taxes on the rich and in those that didn’t, the study found.” …Hope and Limberg…confirmed there is “strong evidence that cutting taxes on the rich increases income inequality but has no effect on growth or unemployment.” …Sold as a prosperity booster, trickle-down tax cuts for the very rich do not increase prosperity, growth or employment for the average American.

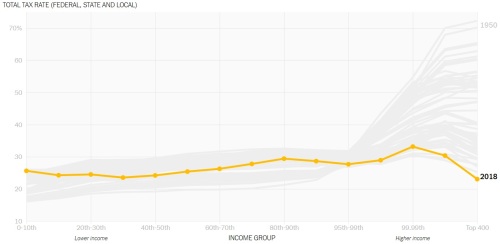

…“Is it the norm?” the fact-checking outfit Politifact asked. “No.” Time for an update: It’s the norm now. …the 400 wealthiest Americans last year paid a lower total tax rate — spanning federal, state and local taxes — than any other income group, according to newly released data. …That’s a sharp change from the 1950s and 1960s, when the wealthy paid vastly higher tax rates than the middle class or poor.

…“Is it the norm?” the fact-checking outfit Politifact asked. “No.” Time for an update: It’s the norm now. …the 400 wealthiest Americans last year paid a lower total tax rate — spanning federal, state and local taxes — than any other income group, according to newly released data. …That’s a sharp change from the 1950s and 1960s, when the wealthy paid vastly higher tax rates than the middle class or poor.

Simply stated, the rich didn’t pay a lot of tax when rates were extortionary because

Simply stated, the rich didn’t pay a lot of tax when rates were extortionary because