A key insight of international economics is that there should be “convergence” between rich countries and poor countries, which is just another way of saying that low-income nations – all other things being equal – should grow faster than high-income nations and eventually attain the same level of prosperity.

The theory is sound, but it’s very important to focus on the caveat about “all other things being equal.” As I explain in this interview from my last trip to Australia, countries with bad policy will grow slower than nations that follow the right policies.

When I discuss convergence, I often share the data on Hong Kong and Singapore because those jurisdictions have caught up to the United States. But I make sure to explain that the convergence was only possible because of good policy.

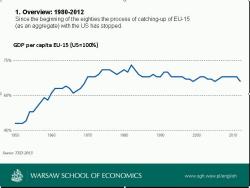

I also share the data showing that Europe was catching up to the United States after World War II, just as predicted by the theory, but then convergence ground to a halt once those nations imposed some bad policy – such as costly welfare states.

I also share the data showing that Europe was catching up to the United States after World War II, just as predicted by the theory, but then convergence ground to a halt once those nations imposed some bad policy – such as costly welfare states.

In other words, convergence is a choice, not destiny.

Countries with small government and laissez-faire markets are the ones that grow and converge. The nations with statist policy languish and suffer. Or even de-converge (with Argentina and Venezuela being depressing examples).

Let’s see what academics have to say about this issue.

We’ll start by looking at some research at VoxEU by Professor Linda Yueh. She wants to understand the characteristics that determine national prosperity.

It’s a long-standing economic question as to why more countries are not prosperous. …The World Bank estimates that of the 101 middle-income economies in 1960, just a dozen or so had become prosperous by 2008…

But, hundreds of millions of people have joined the middle classes. …How has this been achieved? Possessing good institutions is what economists have come to focus on and the spread of such institutions seems to have been key…the father of New Institutional Economics…Douglass North…stressed that there was no reason why countries could not learn from more successful economies to better their own institutions. That finally happened in the 1990s.

I’m a fan of Douglass North since he – along with many other winners of the Nobel Prize – has endorsed tax competition.

In his case, the goal was for nations to face pressure to adopt good institutions.

And Professor Yueh explains that this means rule of law and free markets.

China, India, and Eastern Europe changed course. China and India re-oriented their economies outward to integrate with the world economy, while Eastern Europe shed the old communist institutions and adopted market economies. In other words, having tried central planning (in China and the former Soviet Union) and import substitution industrialisation (in India), these economies abandoned their old approaches and adopted as well as adapted the economic policies of more successful economies. For instance, China, which has accounted for the bulk of poverty reduction since 1990, undertook an ‘open door’ policy that sought to integrate into global production chains which increased competition into its economy that had been dominated by state-owned enterprises. India likewise abandoned its previous protectionist policies…in Central and Eastern Europe. Communism gave way to capitalism, with these nations adopting entirely new institutions that re-geared their economies toward the market.

All of this is good news, but not great news. Simply stated, partial liberalization can lift people out of poverty.

But it takes comprehensive liberalization for a nation to become genuinely rich.

As many of these economies, especially China, have become middle-income countries, their economic growth is slowing down. And they may slow down so far that they never become rich. But, their collective growth has lifted a billion people of out of extreme poverty.

Let’s now see what other scholars say about convergence.

Some new research from the St. Louis Federal Reserve examines this topic. Here’s the mystery they want to address.

Over the past half-century, world income disparities have widened. The gap in real gross domestic product (GDP) per capita relative to the United States between advanced and poor countries has increased.For example, the ratio of average real GDP per capita among the top 10 percent of countries to the bottom 10 percent has increased from less than 20 in 1960 to more than 40 in 1990, and to more than 50 since the turn of the new millennium… The main point to be addressed in this article is why the income disparities between fast-growing economies and development laggards have widened.

In other words, they want to understand why some nations converge and some don’t.

We select a set of 10 fast-growing economies. This set includes Asian countries and African economies that are perceived as better performing. In contrast, we select a set of 10 development laggards. Beyond the typical candidates of countries mired in the poverty trap, this set includes countries with similar or even better initial states than some of the fast-growing countries, but with divergent paths of development leading to worse macroeconomic outcomes. That is, among development laggards, we choose two subgroups, one consisting of trapped economies and another of lag-behind countries. …Using cross-country analysis, we find that a key factor for fast-growing countries to grow faster than the United States and for trapped economies to grow slower than the United States is the relative TFP… Overall, we find that institutional barriers have played the most important role, accounting for more than half the economic growth in fast-growing and trapped economies and for more than 100 percent of the economic growth in the lag-behind countries.

Here are their case studies, showing income relative to the United States (a 1.0 means the same degree of prosperity as America).

As you can see, some nations catch up and some fall further behind, while others have periods of convergence and de-convergence.

And what causes these changes?

The degree to which nations have good policy.

…we identify that unnecessary protectionism, government misallocation, corruption, and financial instability have been key institutional barriers causing countries to either fall into the poverty trap or lag behind without a sustainable growth engine. Such barriers have created frictions or distortions to capital markets, trade, and industrialization, subsequently preventing these countries from advancing. …By reviewing the previous country-specific details, one can see that the 10 fast-growing countries have all adopted an open policy… Their governments have undertaken serious reforms, particularly in both labor and financial markets. …Thus, the establishment of correct institutions and individual incentives for better access to capital markets, international trade, and industrialization can be viewed as crucial for a country to advance with sustained economic growth

Here’s a table from the report showing the policies that help and the policies that hurt. Needless to say, it would be good if the White House understood that protectionism is one of the factors that undermine growth.

Interestingly, the study from the St. Louis Federal Reserve includes some country-specific analysis.

Here’s what it said about India, which suffered during an era of statism but has enjoyed decent growth more recently thanks to partial liberalization.

During 1950-90, India’s per capita income grew at an average annual rate of only about 2 percent, a result due to the Indian government’s implementation of restrictive trade, financial, and industrial policies. The Indian state took control of major heavy industries, by including additional licensing requirements, capacity restrictions, and limits on the regulatory framework. …In the late 1970s, the Indian government opened the economy by liberalizing both international trade and the capital market, leading to rapid growth in the early 1990s. As argued by Rodrik and Subramanian (2005), the trigger for India’s economic growth was an attitudinal shift on the part of the national government in 1980 in favor of private businesses. …The final trigger of the major economic reform of Manmohan Singh in the 1990s was due to the well-known 1991 balance-of-payment crisis….This reform ended the protectionist policies followed by previous Indian governments and started the liberalization of the economy toward a free-market system. This event led to an average annual growth rate that exceeded 6 percent in per capita terms during 1990-2005.

For what it’s worth, I am semi-pessimistic about India. Simply stated, there’s hasn’t been enough reform.

We also have some discussion regarding Argentina, which is mostly a sad story of ever-expanding government.

Argentina is the third-largest economy in Latin America and was one of the richest countries in the world in the early twentieth century. However, after the Great Depression, import substitution generated a cost-push effect of high wages on inflation. During 1975-90, growing government spending, large wage increases, and inefficient production created chronic inflation that increased until the 1980s, and real per capita income fell by more than 20 percent. …In 1991, the government attempted to control inflation by pegging the peso to the U.S. dollar. In addition, it began to privatize state-run enterprises on a broader basis and stop the run of government debt. Unfortunately, lacking a full commitment, the economy continued to crumble slowly and eventually collapsed in 2001 when the Argentine government defaulted on its debt. Its GDP declined by nearly 20 percent in four years, unemployment reached 25 percent, and the peso depreciated by 70 percent after being devalued and floated.

But if we go to the other side of the Andes Mountains, we find some good news in Chile.

From the Second World War to 1970, real GDP per capita of Chile increased at an average annual rate of 1.6 percent, and its economic performance was behind those of Latin America’s large and medium-sized countries. Chile pursued an import-substitution strategy, which resulted in an acute overvaluation of its currency that intensified inflation. …Although most Latin American countries have practiced strong government intervention in the markets since the mid-1970s, Chile pursued free market reform. …The outcomes are as follows: Exports grew rapidly, per capita income took off, inflation declined to single digits, wages increased substantially, and the incidence of poverty plummeted (compare with Edwards and Edwards, 1991). Since the democratic administration of Patricio Aylwin in 1990, the economic reform has been accelerated and Chile has become one of the healthiest economies in Latin America.

Not only has Chile become the richest nation in Latin America, it also has enjoyed significant convergence with the United States. About 40 years ago, according to the Maddison database, per-capita GDP in Chile was only about 20 percent of U.S. levels. Now it is 40 percent.

I’ll close with a chart, based on the Maddison numbers, showing how Hong Kong, Singapore, and Switzerland have converged with the United States. These are the only nations that have ranked in the top-10 for economic freedom ever since the rankings began. As you can see, their reward is prosperity.

The bottom line is that there is a recipe for growth and prosperity. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that very few nations follow the recipe since economic liberty means restricting the power of special interests and the political elite.

[…] of which implies that European economies should be growing faster than the U.S. […]

[…] Even though poor countries are supposed to grow faster than rich countries, the above chart is another example for my anti-convergence […]

[…] explained a few months ago how poor nations can converge with rich […]

[…] the best way of helping poor countries achieve faster growth so they can converge with rich […]

[…] economics, convergence theory is the common-sense observation that poor countries – in general – should grow faster […]

[…] Economists assume that poor countries should grow faster than rich countries over time, a process known as convergence. […]

[…] depressing data about the European Union losing ground compared to the United States, even though convergence theory tells us that should not […]

[…] especially noteworthy is that the gap between the U.S. and E.U. keeps widening even though convergence theory says poorer nations should grow faster than richer […]

[…] Professor Noah Smith shows that Poland was richer than China 30 years ago and – contrary to convergence theory – has become even richer over […]

[…] a big believer in looking at long-run trends, particularly whether countries are experiencing convergence of divergence with regards to per-capita economic […]

[…] that’s true everyplace in the […]

[…] wrote yesterday about how pro-market policies in Estonia are helping that nation catch up (converge) with other European […]

[…] written many times that convergence (or lack thereof) is the way to assess a nation’s economic […]

[…] Leszek Balcerowicz (former head of Poland’s central bank) shows that Western Europe was rapidly converging with the United States, but then began to lose ground after big welfare states were imposed (and […]

[…] Balcerowicz (former head of Poland’s central bank) shows that Western Europe was rapidly converging with the United States, but then began to lose ground after big welfare states were imposed (and […]

[…] are very impressive examples of convergence (as the Asian Tigers caught up with Latin America) followed by divergence (as the Tigers then […]

[…] elaborate, Madrid enjoyed rapid convergence over the past two decades, a period where there was lots of economic liberalization (including de […]

[…] elaborate, Madrid enjoyed rapid convergence over the past two decades, a period where there was lots of economic liberalization (including de […]

[…] explains why Russia is not converging with the United States, as theory would predict. Here is a chart based on the Maddison […]

[…] key principle of economics is convergence, which is the notion that poorer nations generally grow faster than richer […]

[…] After a period of “convergence” after World War II, European countries have actually been falling further behind the United […]

[…] what’s especially remarkable is that the gap is growing rather than shrinking, even though convergence theory tells us Europe should be growing […]

[…] Venezuela used to be much richer than Chile, so it makes sense that Chile began to converge. But now the two countries are part of the anti-convergence club […]

[…] Venezuela used to be much richer than Chile, so it makes sense that Chile began to converge. But now the two countries are part of the anti-convergence club […]

[…] of all types agree with “convergence theory,” which is the notion that poor countries should grow faster than rich […]

[…] European nations tend to have the largest increases, as one might expect based on convergence theory (these nations fell way behind because of communist mismanagement). But the biggest increase was […]

[…] The country needs a Reagan-style agenda (the approach used by Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan) to achieve genuine convergence. […]

[…] widely agree with the theory of “convergence,” which is the (mostly true) idea that poor nations should grow faster than rich […]

[…] interview about European economic policy with Gunther Fehlinger, I pontificated on issues such as Convergence and Wagner’s […]

[…] interview about European economic policy with Gunther Fehlinger, I pontificated on issues such as Convergence and Wagner’s […]

[…] Gunther Fehlinger, I explore the connection between two very important important economic concepts: Convergence and Wagner’s […]

[…] a remarkable gap, and it’s getting larger rather than smaller, even though theory says that shouldn’t […]

[…] a remarkable gap, and it’s getting larger rather than smaller, even though theory says that shouldn’t […]

[…] periodically write about the importance of long-run growth and about the importance of convergence (whether poorer countries are catching up with richer countries, as suggested by […]

[…] I frequently use that GDP data when comparing long-run performance for various nations in order to demonstrates that you get more economic output with free markets […]

[…] part, it takes time for poorer nations to economically converge with richer […]

[…] part, it takes time for poorer nations to economically converge with richer […]

[…] again, there are some important observations embedded in the above […]

[…] again, there are some important observations embedded in the above […]

[…] again, there are some important observations embedded in the above […]

[…] long-run measures of economic freedom in various states – similar to the data I use for my convergence/divergence articles that compare nations. Sadly, we have the former, but don’t have the […]

[…] this month, as part of my ongoing series about convergence and divergence, I wrote about why South Korea has grown so much faster than […]

[…] economics, specifically convergence theory, tells us that poor nations should grow faster than rich […]

[…] The degree to which nations enjoy convergence (or divergence) is generally a consequence of whether they allow free markets and limited […]

[…] final observation is that all this data is contrary to traditional convergence theory, which assumes that poor nations should grow faster than rich […]

[…] part of my recent presentation to IES Europe, here’s what I said (and what I’ve said many times before) about the relationship between economic policy and national […]

[…] isn’t just convergence. Singapore caught up with the U.K., then caught up to the U.S.A., and now has a comfortable […]

[…] notwithstanding convergence theory, that gap probably won’t shrink much in the near future since the United States currently has […]

[…] you can see, even though convergence theory says poor countries should grow faster than rich countries, the gap between the United States and […]

[…] people, when looking at why some nations grow faster and become more prosperous, naturally recognize that there’s a […]

[…] is why I share so many examples showing how market-oriented jurisdictions out-perform statist nations over multi-decade […]

[…] focus is the track record of capitalism vs. socialism. Given the wealth of evidence, that’s a slam-dunk victory for free […]

[…] of the equation. These Asian nations are in the process of industrialization, which means they are getting much richer and therefore have the ability to enjoy much better levels of food, housing, and health […]

[…] In any event, he looks at Argentina’s relative performance over a long period of time, which is the right approach to see if a country is converging or diverging. […]

[…] there’s been some convergence ever since policy makers started liberalizing the Swedish […]

[…] also gave a lecture on comparative economics and looked at nations that converged or diverged over several decades. And this lecture included some material on China’s impressive (but […]

[…] numbers should be very compelling since traditional economic theory holds that incomes in countries should converge. In the real world, however, that only happens if […]

[…] I think comparative economics can be very enlightening, I’m quite pleased to see a new study by David Burton of the […]

[…] A rising tide can lift all boats, which is why I write so often about growth in general and comparative growth between nations in particular. […]

[…] So a relatively poor country can get a very good score. Indeed, they should get comparatively good scores according to convergence theory. […]

[…] que es notablemente deprimente ya que la teoría convencional nos dice que las naciones pobres deberían ponerse al día con las naciones […]

[…] de-converging, which is remarkably depressing since conventional theory tells us that poor nations should be catching up with rich […]

[…] makes this data so remarkable is that convergence theory tells us that poorer nations should grow faster than richer […]

[…] – over multiple decades – the superior performance of market-oriented nations, click here and […]

[…] people who dislike free enterprise, it’s quite common that they will admit (at least once I share some of the evidence) that markets produce more prosperity than […]

[…] theory makes sense to many people because it describes much of what we see in the real […]

[…] nations still have a long way to go. And it’s highly unlikely that either nation will ever fully converge to American living standards unless there is a lot more pro-market reform. Not just in trade, but […]

[…] Chile didn’t just converge. It […]

[…] theory of “economic convergence” is based on the notion that poor nations should grow faster than rich nations and eventually […]

[…] I’m happy to discuss theory when debating economic policy, but I mostly focus on real-world evidence. […]

[…] the convergence literature shows that the same thing is true for developing […]

[…] the convergence literature shows that the same thing is true for developing […]

All candidates for public office should read this and understand the lessons. Candidates from City Council to President and Priminister need to understand the lesson and act upon its tenants.