There are not many advantages to being old, but I feel lucky to have been alive to see the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

We should celebrate this victory over evil every day.

We should celebrate this victory over evil every day.

But especially on December 26, which is the 30th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s downfall (the Soviet flag was replaced by the Russian flag on Christmas, but the USSR wasn’t formally dissolved until the following day).

In a column for the American Institute for Economic Research, Doug Bandow writes joyfully about the end of the Soviet Union.

…the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which Reagan accurately labeled the Evil Empire…assuredly was evil. …the Evil Empire’s death wasn’t the miracle that occurred three decades ago. The Soviet Union’s peaceful death was. …Reagan was vital. He recognized the USSR as a national Humpty Dumpty, ready for its great fall. Contra the widespread assumption among foreign policy specialists that communism was likely to be with us for years, even decades, Reagan saw weakness, economic, to be sure, but also moral and spiritual. …Gorbachev…kept Red Army troops in their barracks in the breakthrough year of 1989, when the East European “satellites” slipped their orbits. …Poland and Hungary began the cascade. Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria followed more slowly. Most dramatically, the Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989, after East Germany’s leadership refused to commit mass murder and mow down protestors. …The Soviet Union staggered along for two more years. The regime increasingly failed to manage the economy. …Three decades ago this month the Evil Empire—created by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, empowered by Joseph Stalin, dessicated by Leonid Brezhnev, and buried by Mikhail Gorbachev—ended. Disappeared. Collapsed. Vanished. Disintegrated. Failed. And all the misguided intellectuals, venal apparatchiks, and murderous ideologues could not put it back together again. …good people can, and sometimes do, win.

Reagan saw weakness, economic, to be sure, but also moral and spiritual. …Gorbachev…kept Red Army troops in their barracks in the breakthrough year of 1989, when the East European “satellites” slipped their orbits. …Poland and Hungary began the cascade. Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria followed more slowly. Most dramatically, the Berlin Wall fell on November 9, 1989, after East Germany’s leadership refused to commit mass murder and mow down protestors. …The Soviet Union staggered along for two more years. The regime increasingly failed to manage the economy. …Three decades ago this month the Evil Empire—created by Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, empowered by Joseph Stalin, dessicated by Leonid Brezhnev, and buried by Mikhail Gorbachev—ended. Disappeared. Collapsed. Vanished. Disintegrated. Failed. And all the misguided intellectuals, venal apparatchiks, and murderous ideologues could not put it back together again. …good people can, and sometimes do, win.

The point about the “moral and economic” weakness of the Soviet Union is probably not sufficiently appreciated.

Reagan pointed out (often using humor) that communism was a moral abomination, not some sort of legitimate competing system (I’d be rich today if I had a dollar for every time some supposed expert asserted that we needed to find a middle ground with communism).

It’s probably not possible to measure the extent to which foundational criticism played a role in the collapse of the Soviet Union, but these excerpts from James Pethokoukis seem very relevant.

December will mark the 30th anniversary of the dissolution of the Soviet Union. …One of the best brief analytical accounts of Soviet Union’s demise is by AEI scholar Leon Aron — a 2011 piece in Foreign Policy, “Everything You Think You Know About the Collapse of the Soviet Union Is Wrong.” …To Aron, the sudden demise of the Soviet Empire is ultimately a story of moral renaissance, an “intellectual and moral quest for self-respect and pride that, beginning with a merciless moral scrutiny of the country’s past and present, within a few short years hollowed out the mighty Soviet state, deprived it of legitimacy, and turned it into a burned-out shell that crumbled… The long-run decline and demise of the Soviet Union is also, of course, a story of the economic failure of socialism and central planning.

…To Aron, the sudden demise of the Soviet Empire is ultimately a story of moral renaissance, an “intellectual and moral quest for self-respect and pride that, beginning with a merciless moral scrutiny of the country’s past and present, within a few short years hollowed out the mighty Soviet state, deprived it of legitimacy, and turned it into a burned-out shell that crumbled… The long-run decline and demise of the Soviet Union is also, of course, a story of the economic failure of socialism and central planning.

While Reagan deserves considerable credit, he wasn’t the only leader to help push the Soviet Union into the dustbin of history.

In an article for Reason, Stephanie Slade discusses the role of Pope John Paul II.

In 1979, less than a year after ascending to the Catholic Church’s highest office, Pope John Paul II returned to his home country, then under communist rule. He disembarked at the airport, knelt, and kissed the Polish ground. That moment was arguably the beginning of the end of the Soviet Union. …While celebrating Mass at Warsaw’s Victory Square, John Paul…said, “that there can be no just Europe without the independence of Poland marked on its map!”  It was an astonishing political rebuke to the Soviets, who following World War II had installed communist governments across Eastern Europe that were “independent” in name only. …As the labor organizer and future Polish president Lech Wałęsa put it, John Paul’s pilgrimage “awakened in us, the Poles, the hope for change….I have no doubt that without the pope’s words, without his presence, the birth of Solidarity would not have been possible.” …In 1987, Pope John Paul II made his third pilgrimage to Poland. Independent unions were still outlawed at the time, but that did not stop supporters from hoisting Solidarity banners during a papal Mass attended by some 800,000 people. That same week, Reagan, during a speech at the Brandenburg Gate, intoned: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Two years later, the Berlin Wall would indeed come down. We often think of that as the first domino to fall in Eastern Europe. But in fact, it occurred a few months after Poland held its first semi-free parliamentary elections. Solidarity claimed 99 percent of the open seats. …The events of the period were a triumph for individual liberty.

It was an astonishing political rebuke to the Soviets, who following World War II had installed communist governments across Eastern Europe that were “independent” in name only. …As the labor organizer and future Polish president Lech Wałęsa put it, John Paul’s pilgrimage “awakened in us, the Poles, the hope for change….I have no doubt that without the pope’s words, without his presence, the birth of Solidarity would not have been possible.” …In 1987, Pope John Paul II made his third pilgrimage to Poland. Independent unions were still outlawed at the time, but that did not stop supporters from hoisting Solidarity banners during a papal Mass attended by some 800,000 people. That same week, Reagan, during a speech at the Brandenburg Gate, intoned: “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall!” Two years later, the Berlin Wall would indeed come down. We often think of that as the first domino to fall in Eastern Europe. But in fact, it occurred a few months after Poland held its first semi-free parliamentary elections. Solidarity claimed 99 percent of the open seats. …The events of the period were a triumph for individual liberty.

I’ve pointed out how a grocery store in Texas also helped bring about the end of the Soviet Union.

A TV show about the same state may have played a role as well. Here are some excerpts from a report in the U.K.-based Sun.

Classic soap Dallas brought down communism in the Soviet Union, Eurythmics star Dave Stewart has claimed. …And the claim comes from an impeccable source — a conversation the songwriter had with former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1990s. Dave, 68, said: “What Gorbachev was saying — it was Dallas, the TV show. …“Somebody managed to get a VHS to work and broadcast it to part of Russia and they thought, ‘Hang on, that’s how people live in America’. “He said that had more effect, that half an hour, than anything else.” …watching such shows was banned behind the Iron Curtain.

had with former Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1990s. Dave, 68, said: “What Gorbachev was saying — it was Dallas, the TV show. …“Somebody managed to get a VHS to work and broadcast it to part of Russia and they thought, ‘Hang on, that’s how people live in America’. “He said that had more effect, that half an hour, than anything else.” …watching such shows was banned behind the Iron Curtain.

For what it’s worth, I don’t think grocery stories and TV shows were quite as important as Reagan and the Pope.

But I think such factors helped to erode the confidence of the communist elite (the bosses who were much more likely to be exposed to the superior economic outcomes in capitalist nations).

Let’s close with a final observation about the failures of the American policy elite.

I’ve previously opined on the glaring inability of some academic economists to understand the inherent flaws of communism. Well, a recent column by George Will contains these amazing observations about a similar blindness by supposed experts inside the U.S. government.

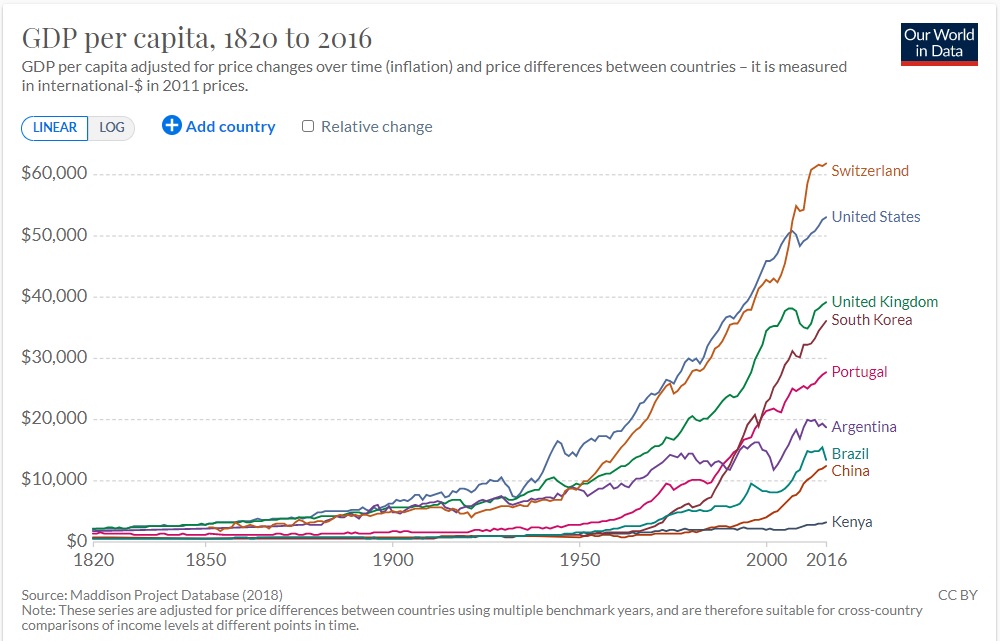

In 1992, Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-N.Y.) remembered a warning by CIA Director Allen Dulles (who would become a Washington casualty of the Bay of Pigs) in 1959 that the Soviet Union’s economy was humming so efficiently that by 1970 the gap between the Soviet and U.S. economies would be dangerously narrow. But, then, the 1957 Gaither Commission projected that the Soviet gross domestic product would surpass the U.S. GDP in 1993. (The sclerotic Soviet Union did not live that long.) Moynihan noted that in 1987 the CIA reported that East Germany’s per capita GDP was higher than West Germany’s, an assessment that “any taxi driver in Berlin” could have refuted.

the gap between the Soviet and U.S. economies would be dangerously narrow. But, then, the 1957 Gaither Commission projected that the Soviet gross domestic product would surpass the U.S. GDP in 1993. (The sclerotic Soviet Union did not live that long.) Moynihan noted that in 1987 the CIA reported that East Germany’s per capita GDP was higher than West Germany’s, an assessment that “any taxi driver in Berlin” could have refuted.

I don’t like majoritarianism, but passages like this are why I’m also not a fan of rule by self-styled experts. But that’s a topic for another day.

The moral of today’s column is that communism was an evil failure.

The moral of today’s column is that communism was an evil failure.

As epitomized by the Soviet Union, it was an economic failure and a humanitarian failure.

P.S. If you want to learn more about the economic performance of East Germany and West Germany, you can click here.

P.P.S. If you want other examples of how communist economics led to terrible outcomes, you can also compare Czechoslovakia to nations in Western Europe, as well as Cuba vs Chile and North Korea vs South Korea.

Read Full Post »