In a recent interview, I got a chance to pontificate about the recipe for growth and prosperity.

Free market capitalism revolutionized the western world, creating prosperity where there used to be deprivation.

But that observation is the easy part. Later in the interview, I was asked to give my two cents on whether Trump’s policies are helping or hurting.

As you can see, I discussed the benefits of pro-growth reforms, but also warned that monetary policy is the wild card and also admitted that economists are lousy forecasters.

That being said, I speculated that there might be a positive surprise for financial markets if Republicans held Congress and investors believed that might lead to some good policies. Especially spending restraint.

Though I should have mentioned – as I have on many occasions – that Trump is sabotaging himself with his protectionist policies.

Since we’re discussing politics and the economy, let’s look at the debate over Trump’s economic stewardship.

Professors Ed Prescott and Lee Ohanian recently opined in the Wall Street Journal about the positive impact of certain Trump policies.

The growth paths in a market economy depend on the quality of government policies and institutions. These affect the incentives to innovate, start a business, hire workers, and invest in physical and human capital.

If policies are reformed to increase incentives for market economic activity—as many have been under President Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress—then investment and labor input expand as the economy rises to a higher growth path. …When policies change to depress these incentives, the economy moves onto a lower long-run growth path. That happened after the 2007-09 recession. …According to our calculations, the U.S. cumulatively lost about $18 trillion in income and output between 2007 and 2016. Everything suggested this shortfall would persist or even grow.

I fully agree that economic performance was anemic during the Obama years. Though I would also give Bush 43 part of the blame.

And I think Prescott and Ohanian are right when they explain that some of Trump’s policies are having a positive effect.

U.S. economic performance is the strongest in years. One policy driving this turnaround is the substantially lower corporate-tax rate, which has made the U.S. more competitive with other countries. Regulatory changes—

such as the partial rollback of Dodd-Frank and new leadership within the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—also have proved helpful, particularly for small businesses, which are benefiting from lower record-keeping and compliance costs. Meanwhile, the number of regulatory pages in the Federal Register has been cut by a third since President Obama’s last year in office. …the U.S. can expect above-normal growth in the coming months, possibly even years.

Moreover, they are correct that more trade is the right approach, not Trump’s myopic protectionism.

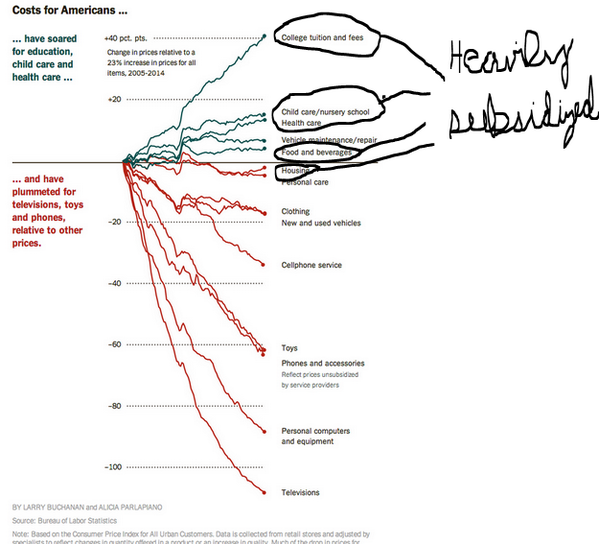

Growth rates could improve with further policy changes. One example is a reduction in trade barriers. Since the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade was signed 70 years ago, international commerce has expanded dramatically, hugely benefiting U.S. consumers by lowering prices and increasing the variety of available goods. The average household’s benefits from trade are greater than $10,000 a year… A second area for reform… The rise of health-care costs is the most important reason wages have not increased more for U.S. workers. The extra compensation is swallowed up by health-insurance premiums. Expanding medical savings accounts and decoupling health plans from employment would create incentives for both consumers and their health-care providers to economize on health-care spending. This would lower costs without compromising quality.

Good health reform would be very beneficial, though I would have explicitly pointed out that the main goal is to mitigate the problems of third-party payer.

Since the economy appears to be doing well, Richard Epstein of the Hoover Institution explores whether Obama deserves any of the credit.

…we easily praise or blame the sitting president for all the economic successes or failures that take place during his term in office. By that standard, President Trump seems to be riding a boom that eluded his predecessor,

and that prospect distresses the legion of Trump critics who regard him as an unmitigated disaster. Accordingly, they hope to credit today’s good times to the work of President Obama. …It is well known that economic policies introduced in one year may well have effects long afterwards. …the key measure is whether a president promotes or frustrates competitive behavior. Under this standard, any protection of monopoly institutions is presumptively bad, while deregulation or tax reduction is presumptively good.

Using that benchmark, Obama gets a bad grade, starting with the faux stimulus but also including Dodd-Frank and other statist policies.

Unsound Obama policies help explain the abnormally low rate of economic growth during his eight-year tenure. …the 2009 stimulus package…left a long-term legacy of protectionist legislation for key businesses and labor unions. …Today’s economic successes come in the face of ARRA, not because of it. Obama pushed through three other major pieces of legislation during his first term, all net negatives. The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) created an immense tangle because it incorporated into health-care insurance many unsustainable features—a rich package of mandatory minimum benefits, community rating, mandatory coverage of preexisting conditions, and poor integration of federal and state programs. …In 2010, …the Dodd-Frank legislation… On balance the legislation did more harm than good by concentrating too many assets in banks deemed too big to fail. It invited regulators to pursue an extended definition of a Systematically Important Financial Institution (SIFI) and with it the opportunity to expand the regulatory scope of Dodd-Frank. …I cannot think of a single mid-level Obama policy that counts as a pro-growth initiative.

Trump, by contrast, is a mix of good and bad.

Deregulation of labor and capital markets are not just a short-term shot in the arm, and the lower taxation of corporate income has worked to repatriate capital from overseas and to expand overall levels of investment. So long as these remain permanent features of the economy—a big “if” with an election coming up—private firms have the necessary time horizons to make much-needed long-term investments. That activity will in turn–as has begun to happen–rejuvenate labor markets. …serious Trump-created obstacles. President Trump is no fan of small domestic budgets, and he has run a perverse rearguard campaign to reverse the declining fortunes of the coal industry. Most importantly, he has waged a series of foolish trade wars against our long-term trading partners. His astounding ignorance on the principles of comparative advantage led Trump to unwisely pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

So what’s the net effect?

Here is the bottom line: the gains from Trump’s (imperfect) domestic program look enormous, given the large economic drag of his trade policies. From this assessment it’s clear that classical liberalism with strong property rights, freedom of contract, and free trade is the only engine to economic prosperity.

I fully agree with the last sentence of that excerpt and I hope the first sentence is true.

But if Trump goes really crazy with his protectionism (and he has lots of bad policies under consideration – dealing with NAFTA, auto trade, China, steel and aluminum, etc), then the net effect of his policies could go from positive to negative.