The debate over socialism shouldn’t even exist. Everywhere big government has been tried, it has failed.

And we have reams of evidence that free-market economies dramatically out-perform statist economies.

And we have reams of evidence that free-market economies dramatically out-perform statist economies.

Yet the siren song of socialism still appeals to a subsection of the population, either because of naiveté or an unseemly lust to exercise power over others.

So let’s once again wade into this debate that shouldn’t be happening.

Writing for the Dallas Morning News, former Texas A&M economics professor Svetozar Pejovich explains that adding “democratic” to “socialism” doesn’t change anything. What really matters is that Sanders and his supporters want bigger government. And that never ends well.

Sanders’ policies…are…incompatible with the American tradition of self-responsibility, self-determination and limited government under a rule of law. …putting those premises into practice requires the acceptance of two institutions: the redistribution of income initiated and monitored by federal government, and the attenuation of private property rights.

And these policies don’t lead to good results, something that Professor Pejovich understands very well given that he was born in the former Yugoslavia.

Of course, the lunch is not free. The short-run consequence of redistributive policies is erosion of the link between performance and reward, which, in turn, reduces economic efficiency and the pie available for redistribution. The long-run cost is the transformation of the American culture of self-responsibility and self-determination into the culture of dependence on the state. …Sanders’ democratic socialism bribes people to voluntarily accept the erosion of private property rights…via laws and regulations. Those law and regulations (such as reducing the right of employers to fire workers at will, giving tenants rights at the expense of apartment owners, granting special privileges to some rent seeking groups, etc.) transfer some decision-making rights from owners to public decision makers, or non-owners. …In the end, the attenuation of private property rights impedes the flow of resources to higher-valued uses and reduces economic efficiency of the economy.

Allow me to augment Professor Pejovich’s analysis by elaborating on how these policies hurt the economy. The redistributionism doesn’t lead to immediate disaster, but it inevitably lures a larger share of the population into dependency over time and the higher taxes required to finance the growing welfare burden gradually erode incentives for work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship.  The combination of those factors slowly but surely dampens the economy’s growth. And as I’ve repeatedly explained, even small difference in growth have enormous long-run implications for a nation’s prosperity.

The combination of those factors slowly but surely dampens the economy’s growth. And as I’ve repeatedly explained, even small difference in growth have enormous long-run implications for a nation’s prosperity.

And there comes a point, particularly given modern demographics, that the system breaks down.

The erosion of property rights has a similar effect, largely by causing a reduction in both the level of investment and the quality of investment. And since every economic theory agrees that capital formation is a key to long-run growth, the net effect of “democratic socialism” it to further weaken potential growth.

What’s especially frustrating is that leftists then point to reduced growth rates as an argument for even bigger government.

I’m not joking. Robert Kuttner of the American Prospect argues that young people are attracted to Sanders because their economic outlook is so grim.

Bernie Sanders has…broad and enthusiastic support, especially among the young…voters who say they are attracted rather than repelled by Sanders’s embrace of socialism. …this is the stunted generation—young adults venturing into a world of work, loaded with student debt, unable to find stable jobs or decent careers.

I basically agree that the economic situation for young people is tepid, but I’m baffled that this is an argument for bigger government since the statist policies of both Bush and Obama deserve much of the blame for today’s sub-par economy.

In other words, we’re seeing Mitchell’s Law in action. Politicians have adopted bad policies that have led to stagnation and now they’re using the resulting economic malaise as an argument for even bigger government. And young people, who are among the biggest victims, are getting seduced.

In other words, we’re seeing Mitchell’s Law in action. Politicians have adopted bad policies that have led to stagnation and now they’re using the resulting economic malaise as an argument for even bigger government. And young people, who are among the biggest victims, are getting seduced.

I’m tempted to simply say young people are too stupid to be allowed to vote, but instead let’s take a serious look at why so many of them are misguided.

Christine Emba of the Washington Post has a column pointing out young people openly embrace socialism.

…it seems that socialism is cool. …socialism does seem to have become the political orientation du jour among voters of a certain (read: young) age. …A January YouGov poll asked respondents whether they had a “favorable or unfavorable” view of socialism and capitalism. While capitalism rated significantly higher overall, those younger than 30 gave socialism higher marks: Forty-three percent viewed it very or somewhat favorably, compared with only 32 percent for capitalism.

The problem is that both Ms. Emba and a lot of young people apparently believe the nonsense spouted by people like Robert Kuttner. They actually blame capitalism for the economic weakness caused by government intervention.

…simple economics have pushed a younger generation of voters to embrace what used to be a dirty word. The past 10 years – for many millennials, the formative years of adulthood – have eroded the credibility of economic [classical] liberalism. The financial crisis and recession weakened youths’ faith in markets… Yet they were also told that the solution to the these problems was more [classical] liberal capitalism. But those solutions haven’t delivered… Underemployment, excessive debt, out-of-reach health care and delayed life goals are young peoples’ defining concerns, and the traditional assumption – that free markets and limited state intervention lead to good outcomes – just doesn’t ring true to them.

Wow, it’s bad enough that people blame free markets for a government-caused financial crisis, but Ms. Emba (and perhaps others) think that we’ve tried capitalist “solutions” after the crisis.

What planet is she on? Can she identify one thing that Obama has done that would count as a free-market response to the financial crisis? The fake stimulus? Obamacare? Dodd-Frank?

By the way, she points out that young people presumably have no idea what socialism actually entails. They just want traditional welfare-state redistributionism.

…for many millennials, “socialism” is simply shorthand for “vaguely Scandinavian in the best way” – free health care, free education and subsidized child care, a state that supports its citizens rather than leaving them at the mercy of impersonal corporations bent on profit. …the socialism that most millennials want is simply a return to a more muscular form of traditional liberalism, one that would have felt right at home in the administration of FDR.

Given that President Roosevelt was either malicious or ignorant, and given that his policies lengthened and deepened the Great Depression, I’m not exactly encouraged that millennials merely want traditional liberal (as opposed to classical liberal) policies.

Though it’s worth noting (in a very depressing sense) that a lot of young people are embracing more totalitarian versions of socialism. Here are some brief excerpts from a longer article in Vox.

Here are some brief excerpts from a longer article in Vox.

Jacobin has in the past five years become the leading intellectual voice of the American left, the most vibrant and relevant socialist publication in a very long time. …That’s an opportunity that Jacobin is seizing to great effect, even if Sanders isn’t far enough left for their taste. The Sanders campaign “could begin to legitimate the word ‘socialist,’ and spark a conversation around it, even if Sanders’s welfare-state socialism doesn’t go far enough,” Sunkara wrote earlier this year. …Jacobin…now boasts a print circulation of about 20,000 and has gained about 400 more subscribers a week since Bernie started his ascent in November. …even if Bernie fades, there’s still a constituency for socialist ideas — a fact that could turn out to be much more important than the Sanders campaign itself.

And they really, really mean socialism. With all its warts.

“It is unapologetic about its interests in political economy and Marxism…,” Brooklyn College professor Corey Robin, a longtime leftist writer who signed on early and is now a contributing editor at Jacobin, says. …any Jacobin editor would be the first to tell you, Sanders is a normal labor liberal, or at most a social democrat. He doesn’t go far enough. …What we really need, Sunkara insists, is democratic worker control of the means of production. …A number of Jacobin’s contributors are members of the International Socialist Organization (ISO), the largest Trotskyist group in North America. …Sunkara’s allegiances…lie with Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). …Frase recalls working with the Freedom Road Socialist Organization, a post-Maoist group, while in high school.

Sanders is a normal labor liberal, or at most a social democrat. He doesn’t go far enough. …What we really need, Sunkara insists, is democratic worker control of the means of production. …A number of Jacobin’s contributors are members of the International Socialist Organization (ISO), the largest Trotskyist group in North America. …Sunkara’s allegiances…lie with Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). …Frase recalls working with the Freedom Road Socialist Organization, a post-Maoist group, while in high school.

I’m not sure to be more amazed that some people really believe this evil nonsense or more worried that Jacobin may actually represent the future of the left in America.

Time for some good news.

My Cato colleague Emily Ekins writes that young people are not hopeless idiots, at least not all of them. Though she phrases her argument in a much nicer fashion in a column she wrote for the Washington Post.

She starts with grim polling data.

A national Reason-Rupe survey found that 53 percent of Americans under 30 have a favorable view of socialism compared with less than a third of those over 30. Moreover, Gallup has found that an astounding 69 percent of millennials say they’d be willing to vote for a “socialist” candidate for president — among their parents’ generation, only a third would do so.

But she notes that for the most part they don’t actually believe in real socialism.

…millennials tend to reject the actual definition of socialism — government ownership of the means of production, or government running businesses. Only 32 percent of millennials favor “an economy managed by the government,” while, similar to older generations, 64 percent prefer a free-market economy. …what does socialism actually mean to millennials? Scandinavia. …In contrast with the 1960s and ’70s, college students today are not debating whether we should adopt the Soviet or Maoist command-and-control regimes that devastated economies and killed millions.

In other words, the nutjobs at Jacobin are still a minority on the left.

Best of all, young people are capable of learning lessons from the real world.

…as millennials age and begin to earn more, their socialistic ideals seem to slip away. …millennials become averse to social welfare spending if they foot the bill. As they reach the threshold of earning $40,000 to $60,000 a year, the majority of millennials come to oppose income redistribution, including raising taxes to increase financial assistance to the poor. …When tax rates are not explicit, millennials say they’d prefer larger government offering more services (54 percent) to smaller government offering fewer services (43 percent). However when larger government offering more services is described as requiring high taxes, support flips and 57 percent of millennials opt for smaller government with fewer services and low taxes, while 41 percent prefer large government.

And she explains that previous generations also have shifted away from big government.

In the 1980s, the same share (52 percent) of baby boomers also supported bigger government, and so did Generation Xers (53 percent) in the 1990s. Yet, both baby boomers and Gen Xers grew more skeptical of government over time and by about the same magnitude. Today, only 25 percent of boomers and 37 percent of Gen Xers continue to favor larger government.

My two cents, for what it’s worth, is that the infatuation with socialism (however defined) among the young underscores why it is so important to “win the narrative” about the causes of the financial crisis and the resulting weak economy.

To the extent that voters actually think capitalism caused the mess in 2008, they will be susceptible to statist ideologies.

In some sense, this is history repeating itself. The Great Depression largely was caused by misguided policies from Hoover and Roosevelt. Yet the left very cleverly peddled the story that capitalism had failed. As a result, generations of voters were more sympathetic to big government.

Thank goodness there are places such as the Cato Institute that are working to correct the narrative, not only about the Great Depression, but also with regards to the financial crisis.

Let’s close with a clever description of the difference between various strains of statism.

I put forth a similar analysis back in 2014, but I confess it wasn’t as clever as the above image. Or as clever as the sign I recently shared.

And let’s not forget the famous two-cow explanation of various ideologies.

Read Full Post »

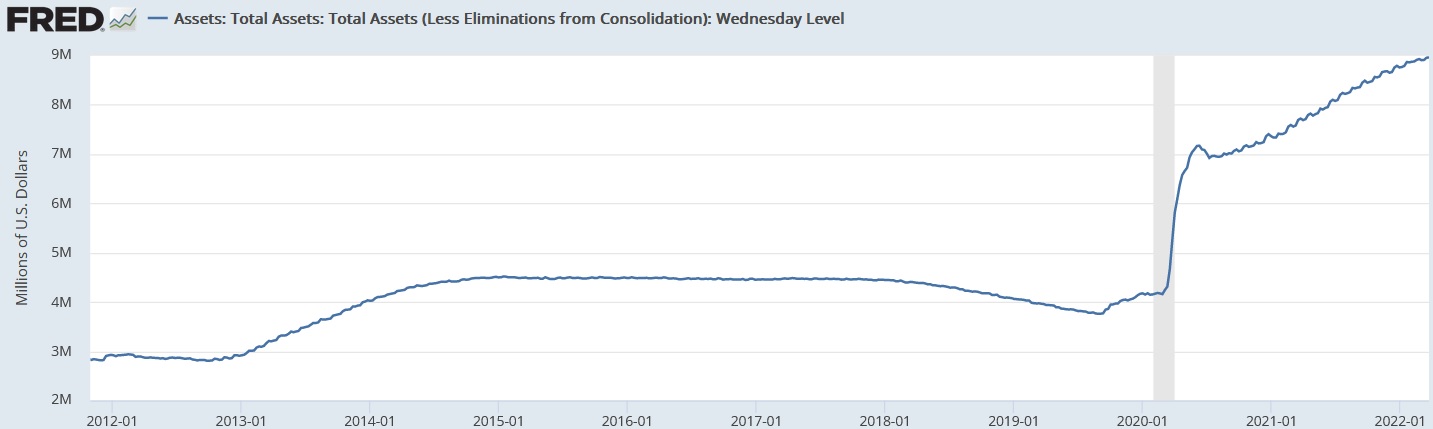

Especially in a world where many of them think the Fed should prop up or bailout Wall Street.

Especially in a world where many of them think the Fed should prop up or bailout Wall Street.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb has made a career of going against the grain, and he has been successful enough that the title of his book The Black Swan is a catchphrase for global unpredictability far beyond its Wall Street origins. …His newest project is helping governments get smarter about risks.

Nassim Nicholas Taleb has made a career of going against the grain, and he has been successful enough that the title of his book The Black Swan is a catchphrase for global unpredictability far beyond its Wall Street origins. …His newest project is helping governments get smarter about risks.