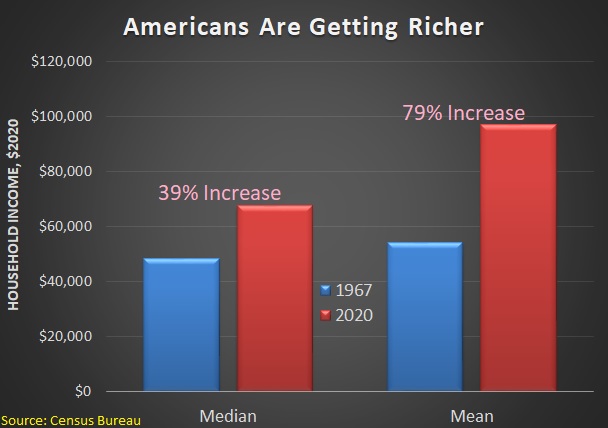

Assuming that income and wealth are honestly earned (rather than from government favoritism), I don’t worry or object to some people being rich. Indeed, I celebrate their success.

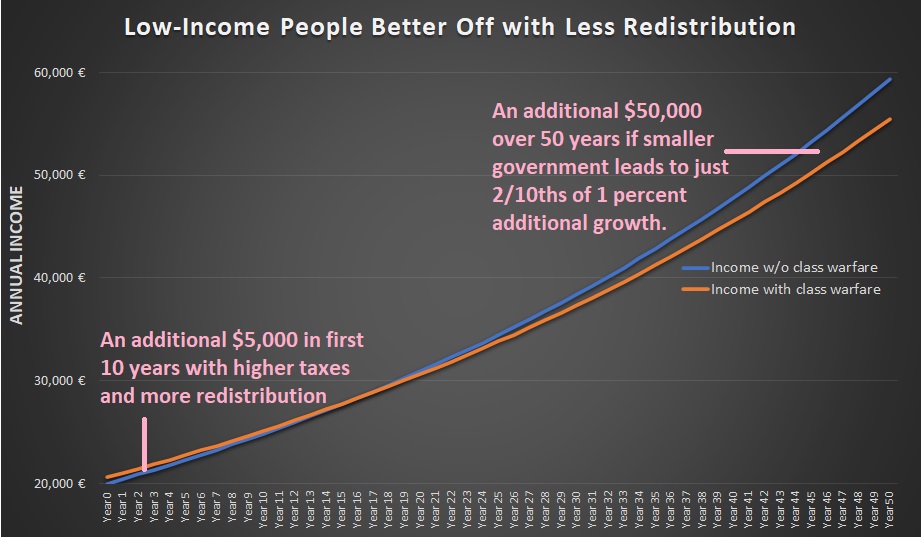

Some friends on the left, however, mistakenly think the economy is a fixed pie. They want us to believe that if Person A gets more income, then Person B gets less.

Some friends on the left, however, mistakenly think the economy is a fixed pie. They want us to believe that if Person A gets more income, then Person B gets less.

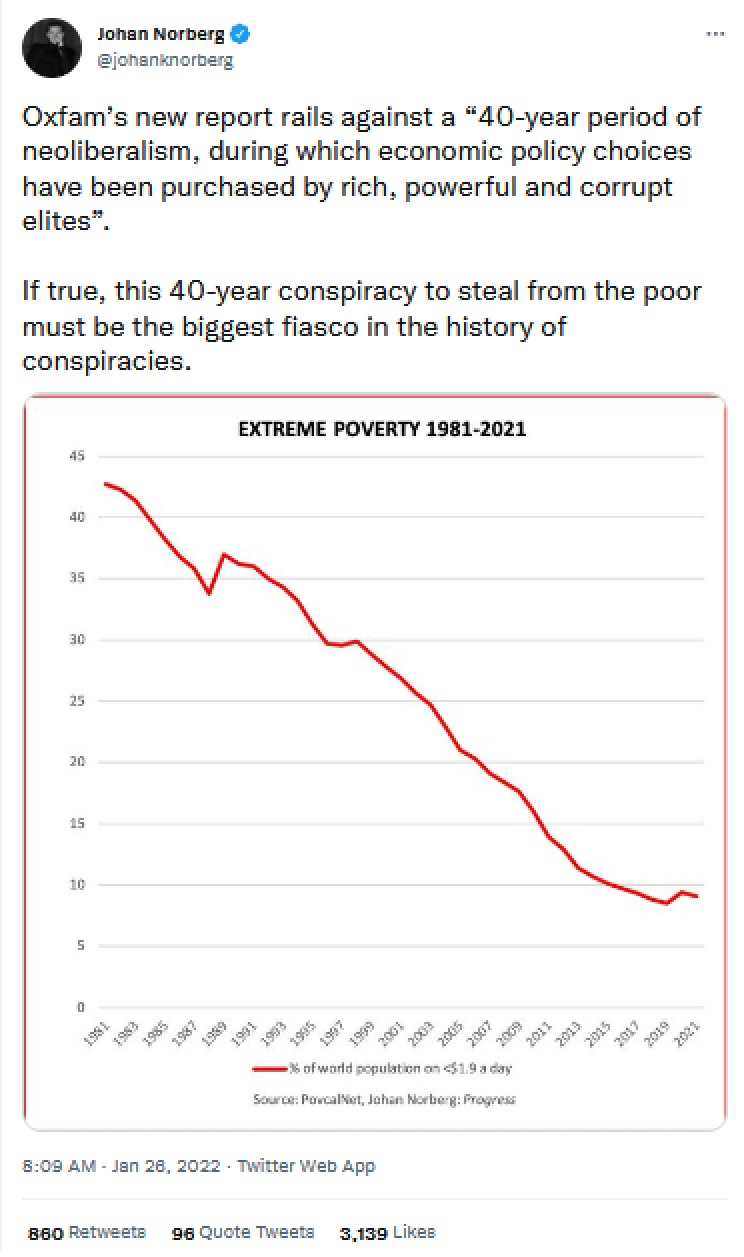

That’s wrong. Wildly wrong.

Other people on the left are simply motivated by envy. A few of them are so spiteful that they would gladly lower everyone’s incomes so long as rich people suffered the biggest drop.

That’s despicable. Utterly despicable.

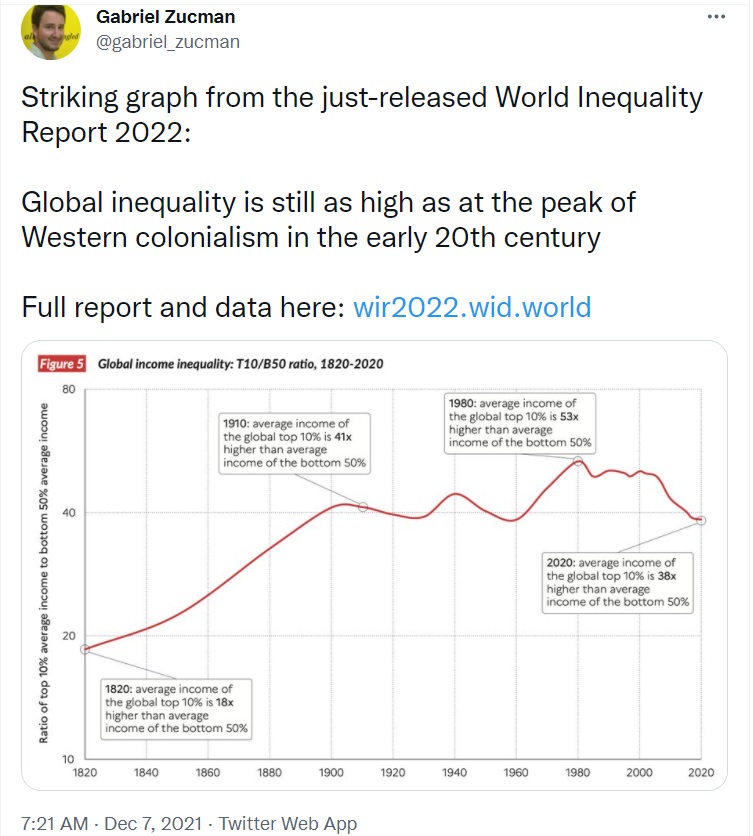

Regardless of motive, advocates of class warfare often point to the data produced by left-leaning economists such as Thomas Piketty, along with others such as Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez.

But it turns out that Piketty, et al, have concocted bad numbers.

Phil Magness of the American Institute for Economic Research and Vincent Geloso of George Mason University have a new article summarizing the latest scholarly research. They start by noting that Piketty is beloved by the media for his “U-curve” that supposedly shows “US inequality today is higher than it was in 1929.”

Thomas Piketty is well-known for his work on estimating income and wealth inequality. That work made him an “economics rockstar” in the eyes of the media…

The main culprit behind rising inequality, according to his story, is a series of tax cuts beginning with the Reagan administration. …academic articles — often co-authored with Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez — are deemed as novel and important contributions to the scholarly literature on inequality.

Magness and Geloso then document some of their mistakes.

What if Piketty and his team got the numbers wrong though? …There would no longer be an empirical case for hiking taxes or expanding government redistribution. …In a recent working paper, we…looked at the ways that Piketty and his coauthors handled the underlying tax statistics. …errors pervade the entire Piketty-Saez series. After correcting for these problems, we found that Piketty and his co-authors tend to underestimate total personal income earnings, thereby artificially pumping up the income shares of the richest earners. They do so inconsistently though… In earlier works published in The Economic Journal and Economic Inquiry, we also found other signs of carelessness by Piketty and his acolytes… When we corrected all of these issues, we found that inequality was far lower… As the study and measurement of inequality progresses, Piketty’s (and his team’s) main estimates have become obsolete and might be properly consigned to the field of the history of economic thought. …Piketty’s own data are deeply suspect and open to challenges that he simply does not want to answer.

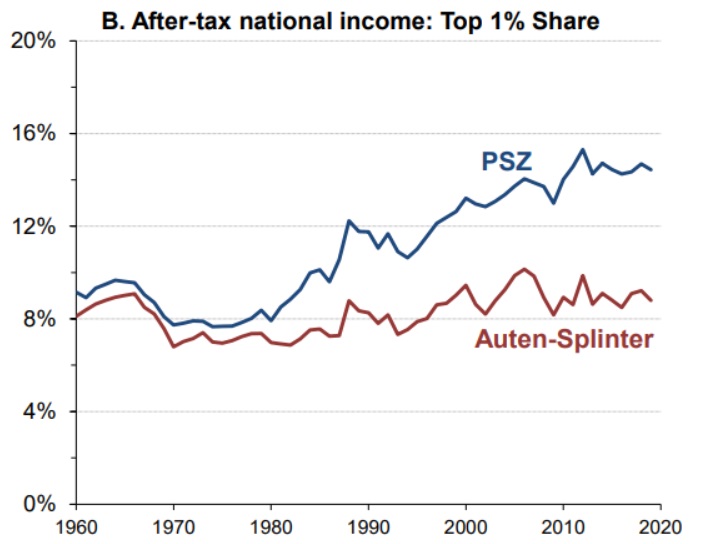

The authors cite other scholarly research, including this chart from David Splinter and Gerald Auten in the Journal of Political Economy.

They discuss that paper, as well as other academic articles.

Auten and Splinter revisited many of the data construction assumptions made by Piketty and his acolytes in dealing with data from 1960 to 2020. Most notably, they made sure that income definitions were consistent over time, that the proper households were considered… After accounting for transfers and taxes (something that Piketty and Saez fail to do), Auten and Splinter find virtually no changes since 1960. …Other works have confirmed these points differently. A small list of these suffices to show this. Miller et al. in an article in Review of Political Economy showed that most of the increase from 1986 onward is due to tax shifting behavior linked to the 1986 Tax Reform. Armour et al. in an article in the American Economic Review showed that properly measuring capital gains eliminates all the increase since 1989. In subsequent work in the Journal of Political Economy, Armour et al. confirmed this finding. Finally, a National Bureau of Economic Research by Smith et al. confirmed that all of these findings also apply to wealth inequality. Moreover, work by Sylvain Catherine et al. from the University of Pennsylvania shows that Piketty and his team failed to properly consider the role of social security.

The whole AIER article is worth reading.

I also recommend this thread from one of the authors.

Today’s column already is too long, but there are many other articles that debunk Piketty and the rest of the class-warfare crowd. To see the views of other authors, click here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

My views, for what it’s worth, are summarized here.