With both France and Greece deciding to jump out of the left-wing frying pan into the even-more-left-wing fire, European fiscal policy has become quite a controversial topic.

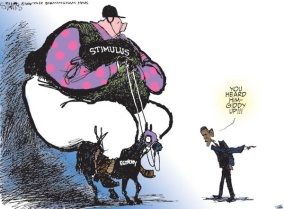

But I find this debate and discussion rather tedious and unrewarding, largely because it pits advocates of Keynesian spending (the so-called “growth” camp) against supporters of higher taxes (the “austerity” camp).

Since I’m a big fan of nations lowering taxes and reducing the burden of government spending, I would like to see the pro-tax hike and the pro-spending sides both lose (wasn’t that Kissinger’s attitude about the Iran-Iraq war?). Indeed, this is why I put together this matrix, to show that there is an alternative approach.

One of my many frustrations with this debate (Veronique de Rugy is similarly irritated) is that many observers make the absurd claim that Europe has implemented “spending cuts” and that this approach hasn’t worked.

Here is what Prof. Krugman just wrote about France.

The French are revolting. …Mr. Hollande’s victory means the end of “Merkozy,” the Franco-German axis that has enforced the austerity regime of the past two years. This would be a “dangerous” development if that strategy were working, or even had a reasonable chance of working. But it isn’t and doesn’t; it’s time to move on. …What’s wrong with the prescription of spending cuts as the remedy for Europe’s ills? One answer is that the confidence fairy doesn’t exist — that is, claims that slashing government spending would somehow encourage consumers and businesses to spend more have been overwhelmingly refuted by the experience of the past two years. So spending cuts in a depressed economy just make the depression deeper.

And he’s made similar assertions about the United Kingdom, complaining that, “the government of Prime Minister David Cameron chose instead to move to immediate, unforced austerity, in the belief that private spending would more than make up for the government’s pullback.”

So let’s take a look at the actual data and see how much “slashing” has been implemented in France and the United Kingdom. Here’s a chart with the latest data from the European Union.

I’m not sure how Krugman defines austerity, but it certainly doesn’t look like there’s been a lot of “slashing” in these two nations.

To be fair, government spending in the United Kingdom has grown a bit slower than inflation in the past couple of years, so one could say that there’s been a very modest bit of trimming.

There’s been no fiscal restraint in France, however, even if one uses that more relaxed definition of a cut. The only accurate claim that can be made about France is that the burden of government spending hasn’t been growing quite as fast since the crisis began as it was growing in the preceding years.

This doesn’t mean there haven’t been any spending cuts in Europe. The Greek and Spanish governments actually cut spending in 2010 and 2011, and Portugal reduced outlays in 2011.

But you can see from this chart, which looks at all the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain), that the spending cuts have been very modest, and only came after years of profligacy. Indeed, Greece is the only nation to actually cut spending over the 3-year period since the crisis began.

Krugman would argue, of course, that the PIIGS are suffering because of the spending cuts. And since there actually have been spending cuts in the last year or two in these nations, does that justify his claims?

Yes and no. I don’t agree with the Keynesian theory, but that doesn’t mean it is easy or painless to shrink the burden of government. As I wrote earlier this year, “…the economy does hit a short-run speed bump when the public sector is pruned. Simply stated, there will be transitional costs when the burden of public spending is reduced. Only in economics textbooks is it possible to seamlessly and immediately reallocate resources.”

What I would argue, though, is that these nations have no choice but to bite the bullet and reduce the burden of government. The only other alternative is to somehow convince taxpayers in other nations to make the debt bubble even bigger with more bailouts and transfers. But that just makes the eventual day of reckoning that much more painful.

Additionally, I think much of the economic pain in these nations is the result of the large tax increases that have been imposed, including higher income tax rates, higher value-added taxes, and various other levies that reduce the incentive to engage in productive behavior.

So what’s the best path going forward? The best approach is to implement deep and meaningful spending cuts, and I think the Baltic nations of Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia are positive role models in this regard. Let’s look at what they’ve done in recent years.

As you can see from the chart, the burden of government spending was rising at a reckless rate before the crisis. But once the crisis hit, the Baltic nations hit the brakes and imposed genuine spending cuts.

The Baltic nations went through a rough patch when this happened, particularly since they also had their versions of a real estate bubble. But, as I’ve already argued, I think the “cold turkey” or “take the band-aid off quickly” approach has paid dividends.

The key question is whether nations can maintain spending restraint, particularly when (if?) the economy begins to grow again.

Even a basket case like Greece can put itself on a good path if it follows Mitchell’s Golden Rule and simply makes sure that government spending, in the long run, grows slower than the private economy.

The way to make that happen is to implement something similar to the Swiss Debt Brake, which effectively acts as an annual cap on the growth of government.

In the long run, of course, the goal should be to shrink the overall burden of government to its growth-maximizing level.

Read Full Post »

Keynesian economists, by contrast, think it is very important to distinguish between the long run and short run. In the long run, they generally would agree with the previous paragraph.

Keynesian economists, by contrast, think it is very important to distinguish between the long run and short run. In the long run, they generally would agree with the previous paragraph. when Harding slashed spending in the early 1920s).

when Harding slashed spending in the early 1920s).