A Supreme Court Justice pointed out in 1932 that “a state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

Well, we’ve had several experiments in higher taxes and higher spending, and they don’t work.

States with heavier fiscal burdens are accumulating ever-higher levels of debt (especially unfunded liabilities) while also causing an ever-greater exodus of taxpayers to other states.

In the long run, this is a recipe for fiscal crisis since it’s hard to give away lots of money if there aren’t enough taxpayers to finance that profligacy (as illustrated by this set of cartoons).

Well, with the help of the coronavirus, the long run may have arrived.

But the pandemic only exposed a problem that already existed.

Mitch Daniels, the former governor of Indiana, wrote two years ago in the Washington Post that poorly manged states like Connecticut shouldn’t be bailed out by taxpayers in better-run states.

…several of today’s 50 states have descended into unmanageable public indebtedness. …in terms of per capita state debt, Connecticut ranks among the worst in the nation, with unfunded liabilities amounting to $22,700 per citizen. Each profligate state is facing its own budgetary perdition for different reasons, but most share common factors. The explosion of Medicaid spending, even before Obamacare, has devoured state funds… In parallel, public pensions of sometimes grotesque levels guarantee that the fiscal strangulation will soon get much worse. In California, some retired lifeguards are receiving more than $90,000 per year. A retired university president in Oregon received $76,000 per month — and no, that’s not a typo. These are the modern-day welfare queens… More and more desperate tax increases haven’t cured the problem; it’s possible that they are making it worse. When a state pursues boneheaded policies long enough, people and businesses get up and leave, taking tax dollars with them.

The explosion of Medicaid spending, even before Obamacare, has devoured state funds… In parallel, public pensions of sometimes grotesque levels guarantee that the fiscal strangulation will soon get much worse. In California, some retired lifeguards are receiving more than $90,000 per year. A retired university president in Oregon received $76,000 per month — and no, that’s not a typo. These are the modern-day welfare queens… More and more desperate tax increases haven’t cured the problem; it’s possible that they are making it worse. When a state pursues boneheaded policies long enough, people and businesses get up and leave, taking tax dollars with them.

In a remarkably prescient passage, Daniels speculates about a future emergency that will lead to pressure for a federal bailout.

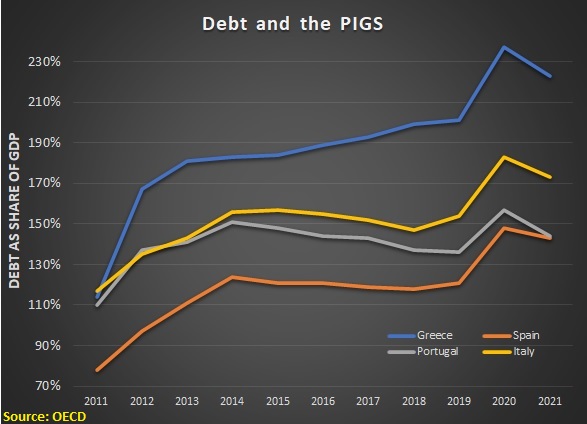

Sometime in the next few years, we are likely to go through our own version of the recent euro-zone drama with, let’s say, Connecticut in the role of Greece and maybe a larger, “too big to fail” partner such as Illinois as Italy. Adding up the number of federal legislators from the 15 or 20 fiscally weakest states, one can count something close to half the votes in the House.

Which brings us to the current situation.

The crowd in Washington has already funneled several hundred billion dollars to state and local governments.

But politicians like Governor Cuomo in New York and Governor Pritzker in Illinois view all that money as an appetizer and now they want the fiscal equivalent of an all-you-can-eat buffet.

The editors of the Wall Street Journal are not sympathetic to these fiscal pyromaniacs.

The question to ask is why taxpayers in Appleton and Sarasota should rescue politicians and unions in Albany and Springfield? …states like New York were already in trouble from their own mismanagement. …take Illinois, where Gov. J.B. Pritzker…raised taxes in 2019 and wants to make the state’s current flat tax progressive…  Yet he and the unions who own the state house have blocked pension or spending reforms. They’ve long bet on a federal bailout, and they see Covid-19 as their main chance. …President Trump has signaled he’s open to a state bailout because, well, he’s open to anything these days. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell caused a stir…when he said states should consider bankruptcy rather than get a bailout. …Mr. McConnell’s larger point is that states shouldn’t get more no-strings cash. Private companies that borrow from the Fed and Treasury have to meet stiff conditions, including limits on compensation, and the same should apply to state governments. Bailout conditions should include cuts in nonessential spending, immediate and permanent reductions in public pension benefits.

Yet he and the unions who own the state house have blocked pension or spending reforms. They’ve long bet on a federal bailout, and they see Covid-19 as their main chance. …President Trump has signaled he’s open to a state bailout because, well, he’s open to anything these days. But Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell caused a stir…when he said states should consider bankruptcy rather than get a bailout. …Mr. McConnell’s larger point is that states shouldn’t get more no-strings cash. Private companies that borrow from the Fed and Treasury have to meet stiff conditions, including limits on compensation, and the same should apply to state governments. Bailout conditions should include cuts in nonessential spending, immediate and permanent reductions in public pension benefits.

Kevin Williamson explains in National Review that the problem is a pre-existing penchant for over-spending and vote-buying.

Bailing out the Illinois state pension system is the worst idea from a week in which we were discussing the health benefits of mainlining Lysol. Irresponsible state and local governments are attempting to exploit the fear and disruption of the coronavirus epidemic to push off the consequences of their decades of reckless and culpably dishonest policies onto the federal government.  … One of the largest problems facing state and local governments, from Illinois to Oklahoma and from Los Angeles to Dallas, is “unfunded liabilities,” meaning the differences between the promises governments have made to their employees and the money they have set aside to pay for those things. …Government workers are a powerful political constituency — they run California — and they want the same thing everybody else does: more. …If Washington were to dump a few billion dollars into the lap of the feckless cartwheeling goobers who run Illinois, the underlying problem of chronic underfunding of future pension liabilities would remain, and Illinois would be right back where it is today in a year or two. A bailout would not solve the problem — it would keep the problem from being solved.

… One of the largest problems facing state and local governments, from Illinois to Oklahoma and from Los Angeles to Dallas, is “unfunded liabilities,” meaning the differences between the promises governments have made to their employees and the money they have set aside to pay for those things. …Government workers are a powerful political constituency — they run California — and they want the same thing everybody else does: more. …If Washington were to dump a few billion dollars into the lap of the feckless cartwheeling goobers who run Illinois, the underlying problem of chronic underfunding of future pension liabilities would remain, and Illinois would be right back where it is today in a year or two. A bailout would not solve the problem — it would keep the problem from being solved.

Adam Michel of the Heritage Foundation explains how bailouts create the wrong incentives.

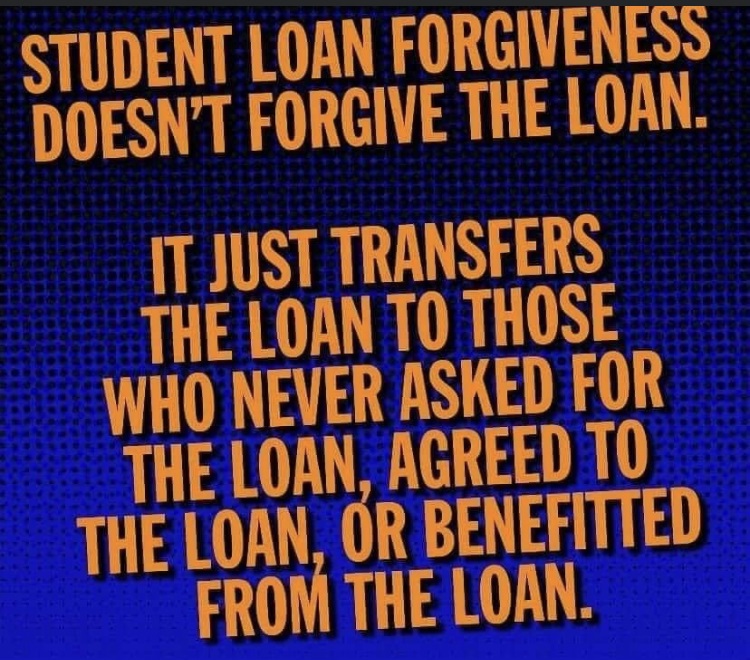

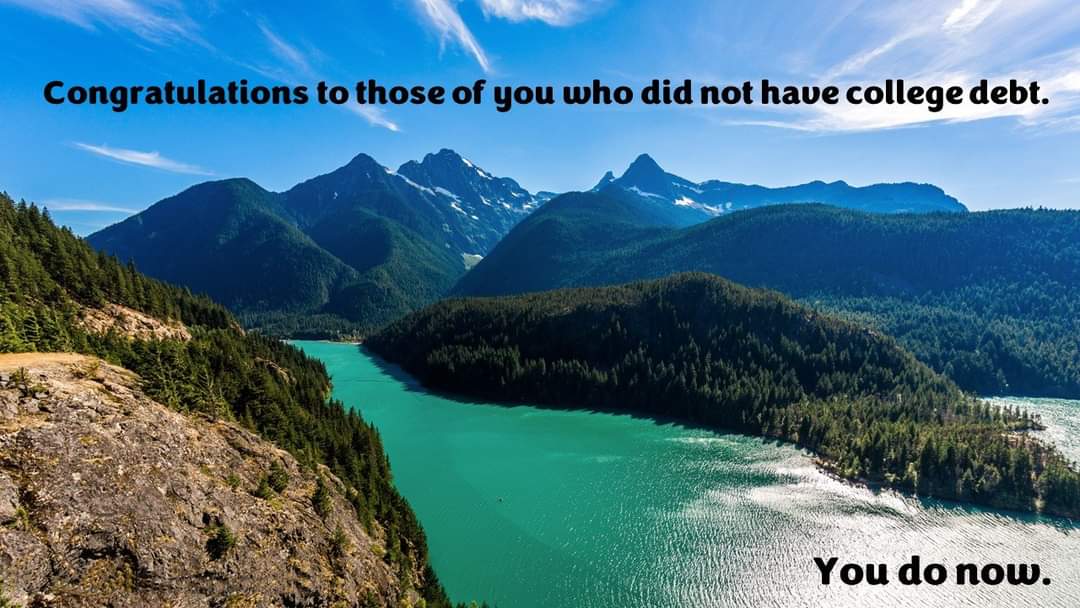

The prospect of federal tax dollars creates an incentive for state legislatures to both expand existing programs beyond sustainable levels, and to simultaneously underfund those programs in hopes of further federal support.  …One example is how states often delay needed infrastructure projects (for which funds are locally available) in hopes of one day receiving federal funds to cover the project costs. …An unrestricted bailout of the states could be highly unequal, forcing taxpayers in well-run states to subsidize those who have systematically underfunded their pensions and rainy day funds, or those states who have particularly volatile revenue systems. …Federal aid tends to expand state budgets and make them less resilient during future crises. Simply moving state funding to the federal government does little more than redistribute local costs to federal taxpayers across all 50 states.

…One example is how states often delay needed infrastructure projects (for which funds are locally available) in hopes of one day receiving federal funds to cover the project costs. …An unrestricted bailout of the states could be highly unequal, forcing taxpayers in well-run states to subsidize those who have systematically underfunded their pensions and rainy day funds, or those states who have particularly volatile revenue systems. …Federal aid tends to expand state budgets and make them less resilient during future crises. Simply moving state funding to the federal government does little more than redistribute local costs to federal taxpayers across all 50 states.

Senator Rick Scott of Florida opines for the Wall Street Journal that taxpayers in his state shouldn’t pick up the tab for New York’s profligate politicians.

…one thing we absolutely shouldn’t do is shield states from the consequences of their own bad budgetary decisions over the past few decades. …Democrats’ true aim: using federal taxpayer dollars to bail out poorly run states—typically, states controlled by Democrats. …Florida is well-positioned to address the coming shortfall in revenue without a bailout. The state may need to make some choices, which is what grown-ups do in tough economic times. And if we need to borrow a small amount in the short term to get us through this economic crisis, that borrowing will be cheaper thanks to our AAA bond rating and the reduction in state debt. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was “irresponsible” and “reckless” not to bail out states like his, a state with two million fewer people than Florida and a budget almost double the size of ours.

…Florida is well-positioned to address the coming shortfall in revenue without a bailout. The state may need to make some choices, which is what grown-ups do in tough economic times. And if we need to borrow a small amount in the short term to get us through this economic crisis, that borrowing will be cheaper thanks to our AAA bond rating and the reduction in state debt. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo said it was “irresponsible” and “reckless” not to bail out states like his, a state with two million fewer people than Florida and a budget almost double the size of ours.

Well stated. Any comparison of Florida and New York shows the benefit of limited government.

Jonathan Williams and Lee Schalk of the American Legislative Exchange Council, opining for the Hill, argue against a bailout.

A growing chorus of governors is calling on Congress to “bail out” state governments. …Their plea comes on the heels of the $2 trillion CARES Act, which included a general $150 billion COVID-19 relief fund, a $30 billion education costs fund, a $45 billion disaster relief fund and more for state and local governments. …History suggests that federal bailouts…incentivize future fiscal irresponsibility and create a moral hazard problem. Bailouts reward fiscally reckless states at the expense of fiscally responsible ones. Academic research from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University shows that federal bailouts could even lead to higher state level taxes. According to their research, every dollar of federal aid to states drives state taxes higher by 33 to 42 cents. …State and local governments do not lack revenue. They lack spending restraint. Over the past 40 years, after fully accounting for increases in population and inflation, state and local direct general spending has grown by 88 percent.

…History suggests that federal bailouts…incentivize future fiscal irresponsibility and create a moral hazard problem. Bailouts reward fiscally reckless states at the expense of fiscally responsible ones. Academic research from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University shows that federal bailouts could even lead to higher state level taxes. According to their research, every dollar of federal aid to states drives state taxes higher by 33 to 42 cents. …State and local governments do not lack revenue. They lack spending restraint. Over the past 40 years, after fully accounting for increases in population and inflation, state and local direct general spending has grown by 88 percent.

The last sentence in the excerpt is key. State politicians have been violating fiscal policy’s Golden Rule by letting spending grow too fast.

What’s needed is TABOR-style spending restraint, as Williams pointed out in a 2015 speech.

So if a bailout is the wrong solution, what’s the right solution? There are three potential options.

Ramesh Ponnuru writes that states should have a process for declaring bankruptcy.

Some states have made exorbitant promises to their employees over the years without providing adequate funding. They made up the difference, on paper, by projecting unrealistically high returns on pension investments. The Federal Reserve, applying a better projection of returns, estimates that pensions are underfunded by $4 trillion. McConnell is right to think that it would be unfair to make Florida’s teachers and firefighters pay for benefits for their counterparts in Illinois, and unwise to create an incentive for further irresponsibility by state officials. …Federal law currently makes no provision for states to re-organize their commitments through bankruptcy proceedings. Creating one would not keep the coronavirus from crushing state budgets. It could, however, prevent, or at least limit, future federal bailouts for state mismanagement of pensions.

estimates that pensions are underfunded by $4 trillion. McConnell is right to think that it would be unfair to make Florida’s teachers and firefighters pay for benefits for their counterparts in Illinois, and unwise to create an incentive for further irresponsibility by state officials. …Federal law currently makes no provision for states to re-organize their commitments through bankruptcy proceedings. Creating one would not keep the coronavirus from crushing state budgets. It could, however, prevent, or at least limit, future federal bailouts for state mismanagement of pensions.

His colleague at National Review, Kevin Williamson, has a different perspective. His article argues that default is better than a Washington-dictated process for bankruptcy.

The several states are not administrative subdivisions of the federal government. They are powers in their own right, superseded by the U.S. government only in certain matters that involve more than one state: Washington can declare war or write immigration law, but it cannot tell Austin how to run the Texas Rangers or Sacramento how to prioritize its finances. Because bankruptcy law is federal law,  putting states into bankruptcy reorganization would upend our basic constitutional arrangement, making state governments answerable to federal bankruptcy judges and, behind them, to Congress. …Sovereigns don’t go bankrupt. Sovereigns default. And that is what is likely to happen with the pension crisis, at least as far as states’ creditors are concerned. It is what should happen. …we should not use the coronavirus as an excuse to federalize the consequences of culpably irresponsible and fundamentally dishonest governance at the state and local level. …If we want debt markets to work, then investors have to pay the price for bad investments. (Lending money to an organization run by Bill de Blasio is a bad decision.) Making creditors take a painful haircut creates incentives to discourage such willy-nilly lending and profligate spending in the future. …Government debt should in this respect be treated like any other debt — and we should change the law to strip municipal bonds of their tax-free status, which creates a subsidy for debt.

putting states into bankruptcy reorganization would upend our basic constitutional arrangement, making state governments answerable to federal bankruptcy judges and, behind them, to Congress. …Sovereigns don’t go bankrupt. Sovereigns default. And that is what is likely to happen with the pension crisis, at least as far as states’ creditors are concerned. It is what should happen. …we should not use the coronavirus as an excuse to federalize the consequences of culpably irresponsible and fundamentally dishonest governance at the state and local level. …If we want debt markets to work, then investors have to pay the price for bad investments. (Lending money to an organization run by Bill de Blasio is a bad decision.) Making creditors take a painful haircut creates incentives to discourage such willy-nilly lending and profligate spending in the future. …Government debt should in this respect be treated like any other debt — and we should change the law to strip municipal bonds of their tax-free status, which creates a subsidy for debt.

And Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute argues in the Wall Street Journal that – if a bailout is offered – it should be accompanied by strict conditions.

Congress may want to offer assistance, but it should come with strict conditions: Any state looking for a pension handout must either live by the stricter accounting rules federal law imposes on private pension plans or freeze its pension and shift all employees to defined-contribution retirement plans. Private-sector plans must assume more-conservative investment returns than public-sector plans and address unfunded liabilities more rapidly. As a result, private pensions today have set aside more than twice as much funding per dollar of promised future benefits than have state and local pensions. …Freezing a pension doesn’t make its unfunded liabilities go away. But it caps existing liabilities while shifting employees to plans in which the government’s funding obligation is clearly defined and can’t be evaded using actuarial or accounting tricks.

Private-sector plans must assume more-conservative investment returns than public-sector plans and address unfunded liabilities more rapidly. As a result, private pensions today have set aside more than twice as much funding per dollar of promised future benefits than have state and local pensions. …Freezing a pension doesn’t make its unfunded liabilities go away. But it caps existing liabilities while shifting employees to plans in which the government’s funding obligation is clearly defined and can’t be evaded using actuarial or accounting tricks.

Of these options, a conditional bailout is not a good idea, even though it is the best way of doing the wrong thing.

Either bankruptcy or default would be a much better choice, and I lean in the direction of default (the same view I have when contemplating Europe’s failing welfare states).

But the right option is to avoid getting in trouble in the first place.

But the right option is to avoid getting in trouble in the first place.

And that means low taxes, spending restraint, and other market-friendly policies.

I’ll simply note that the states most anxious for bailouts are near the bottom in rankings of small government and economic liberty.

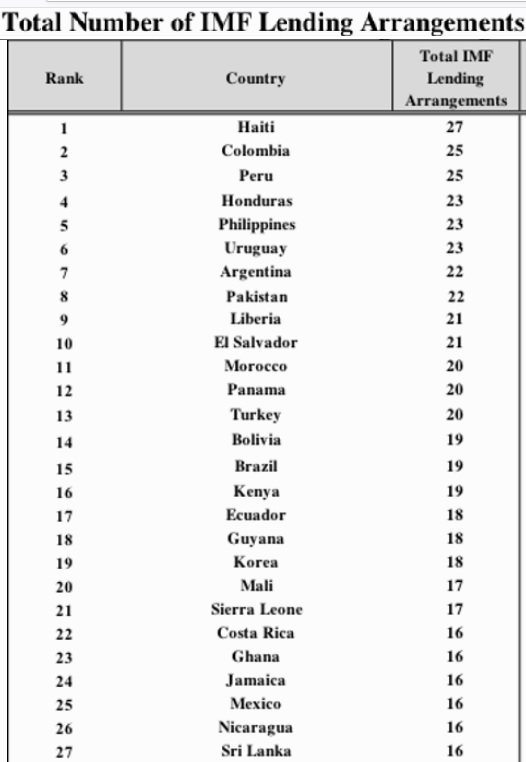

If Washington provides a bailout, that’s a reward for statism and irresponsibility (sort of like foreign aid subsidizing bad policy overseas).

P.S. One month ago, I wrote that the worst coronavirus-related proposal would be restoring the federal tax deduction for state and local tax payments.

I still think that is a terrible idea, of course, but a big bailout from Washington would be even worse.

Read Full Post »

Bipartisanship – It’s possible that Republicans and Democrats cooperate to improve policy (the Clinton years, for instance), but normally bad things happen when the Evil Party and the Stupid Party agree on something. So I’m worried that the two parties will work together in 2023.

Bipartisanship – It’s possible that Republicans and Democrats cooperate to improve policy (the Clinton years, for instance), but normally bad things happen when the Evil Party and the Stupid Party agree on something. So I’m worried that the two parties will work together in 2023.