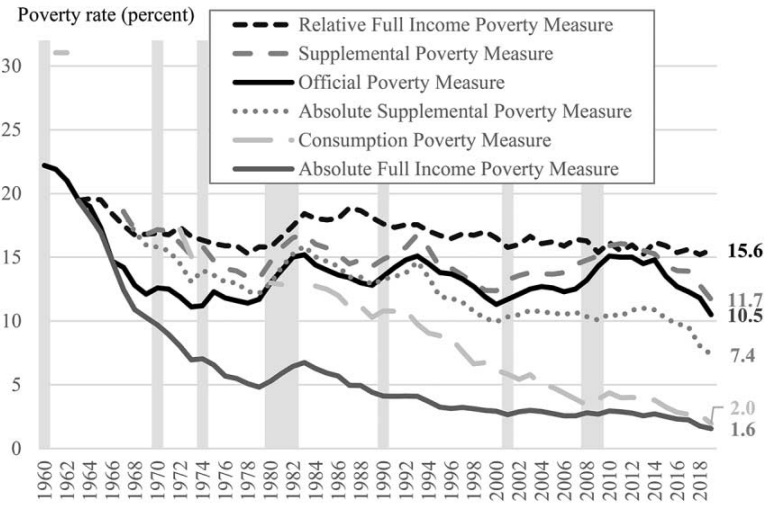

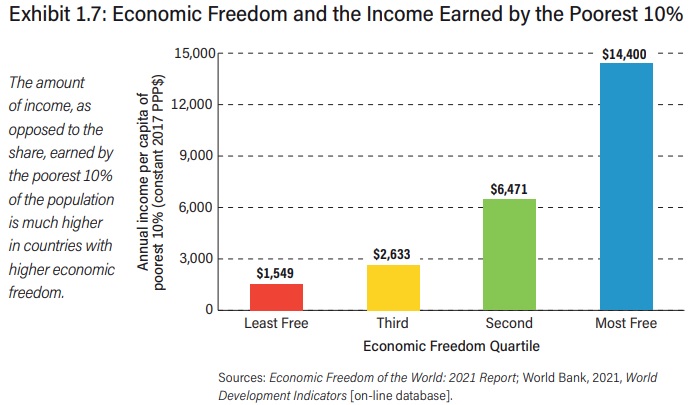

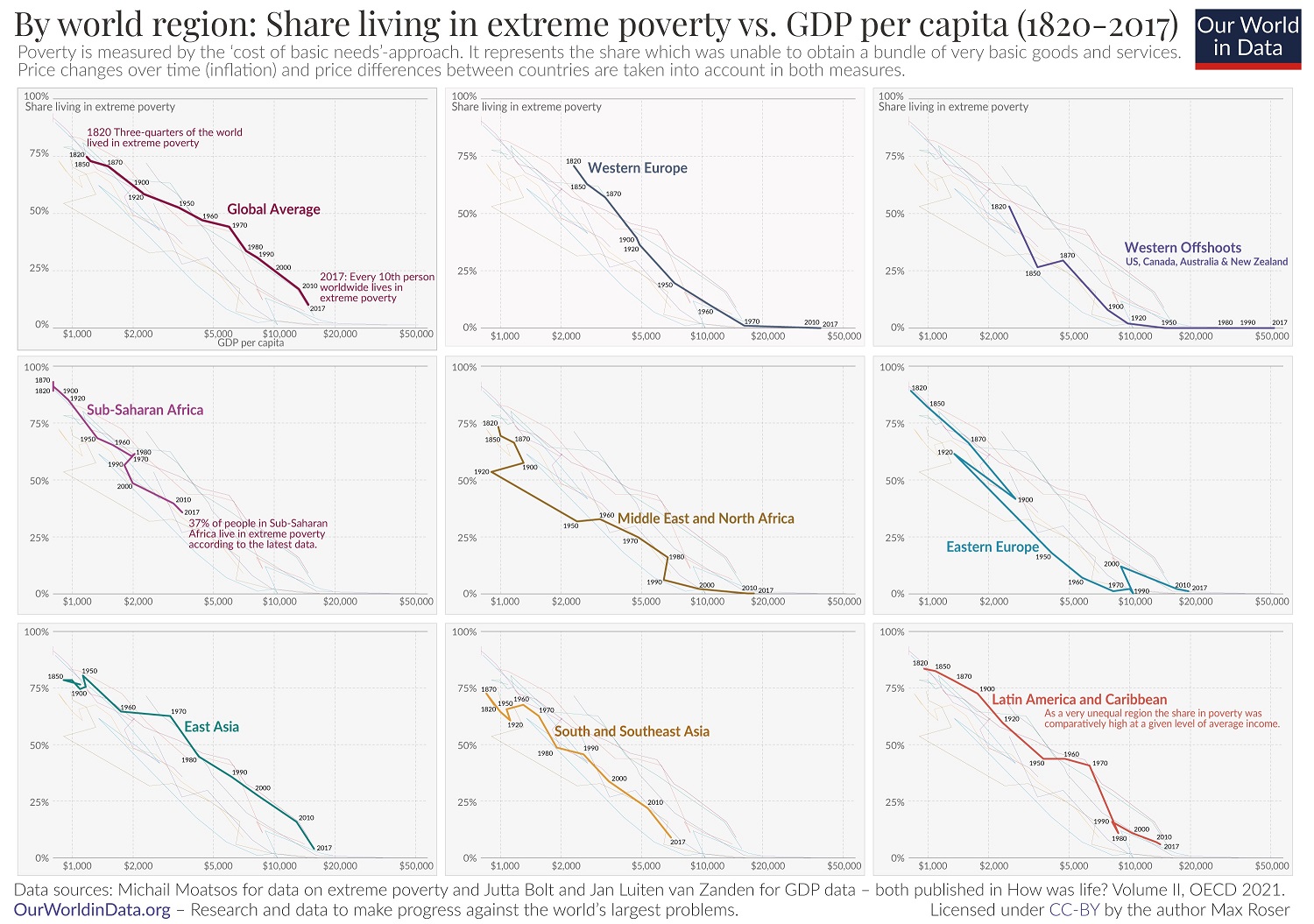

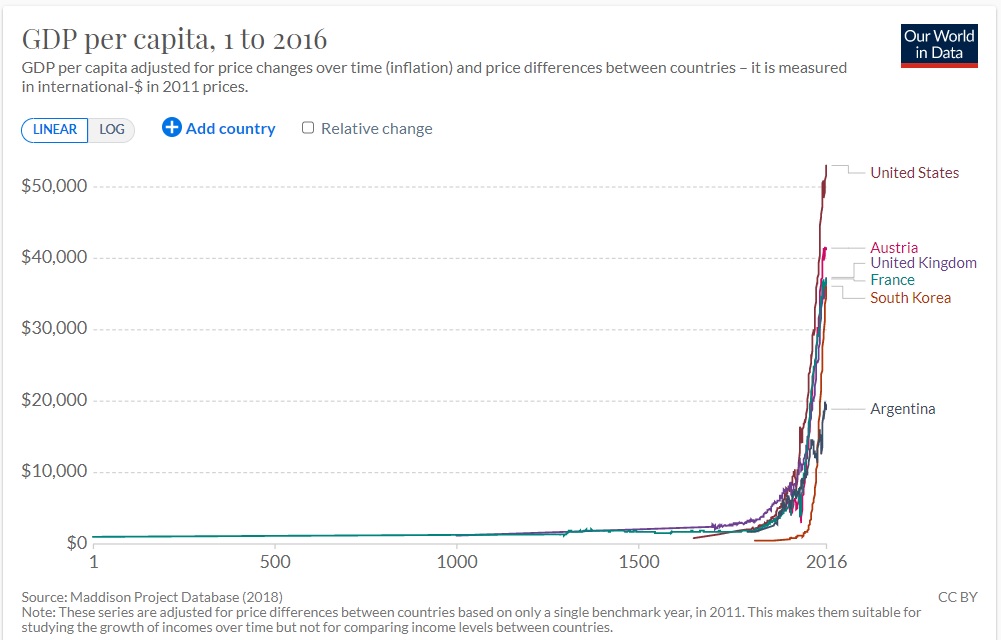

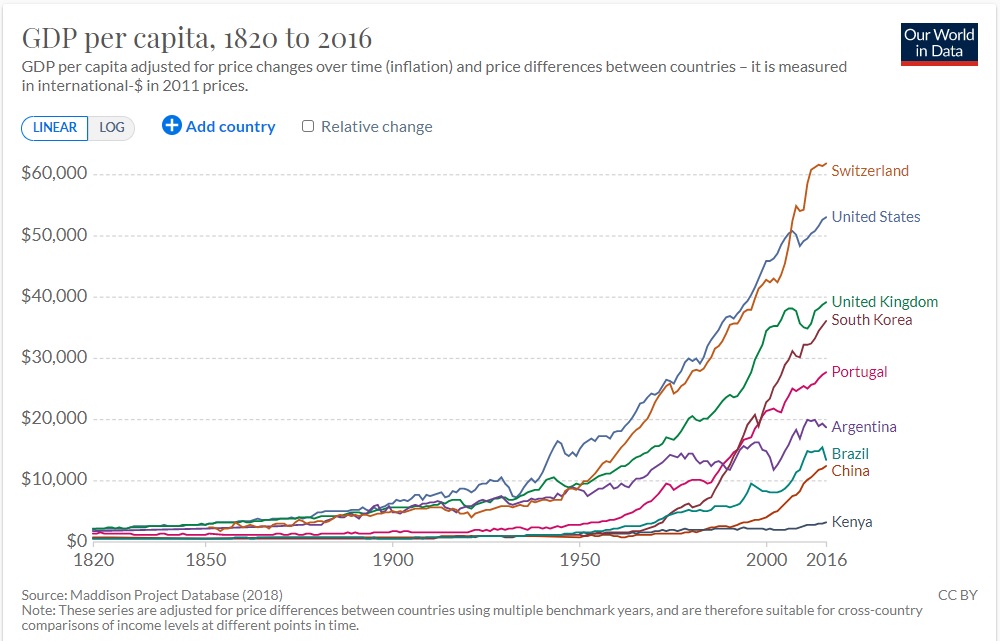

Genuine material deprivation is almost nonexistent in rich nations such as the United States. This is a huge improvement compared to how people lived just 100 or 20o years ago.

Yet public policy fights about poverty will probably never end for the simple reason that people have different goals.

that people have different goals.

- Is the goal to reduce poverty or to reduce dependency?

- Is the goal to reduce poverty or to reduce inequality?

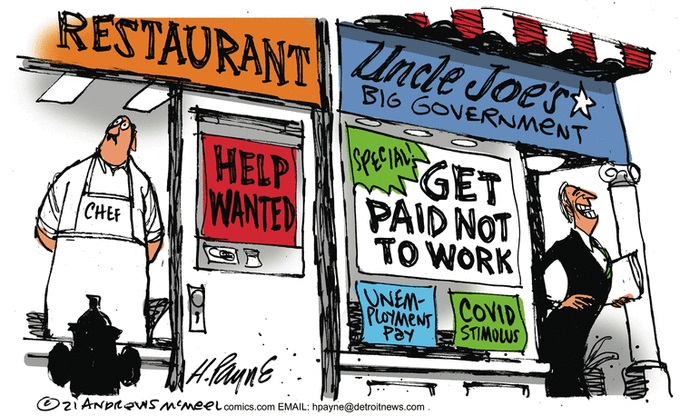

The cartoon is a good illustration of the first question.

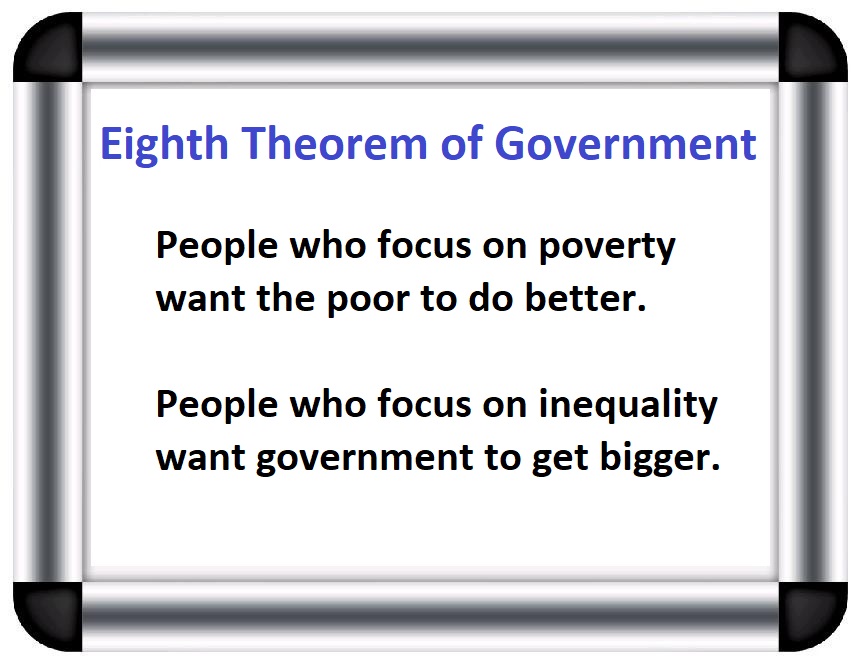

And my Eighth Theorem of Government summarizes the second question.

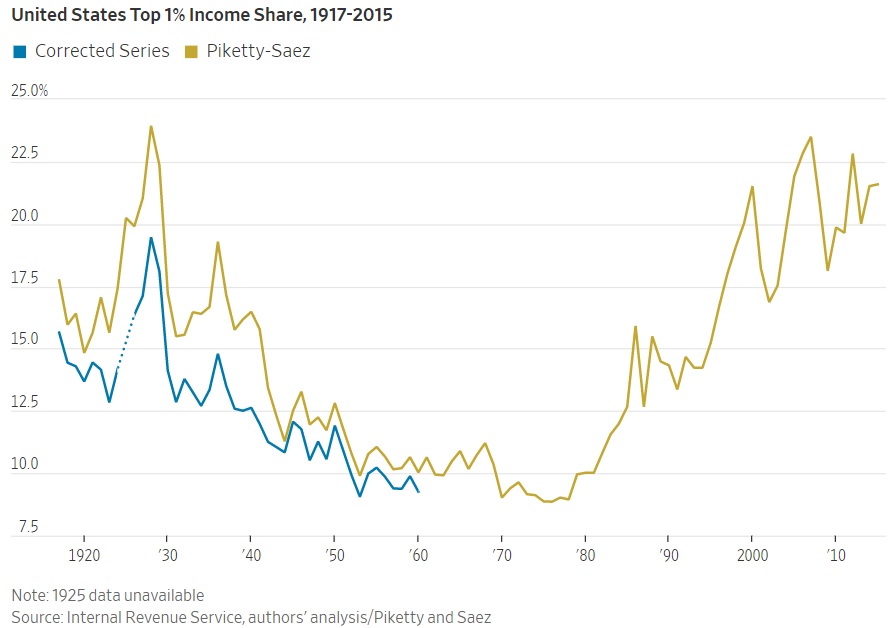

To elaborate on the second question, some of our friends on the left have blurred the distinction between poverty and inequality.

Let’s look at some excerpts from a Project Syndicate article by Teresa Ghilarducci of the New School for Social Research.

America’s retirement system isn’t working. It is failing older workers, pensioners, and would-be retirees, and if we don’t fix it soon,

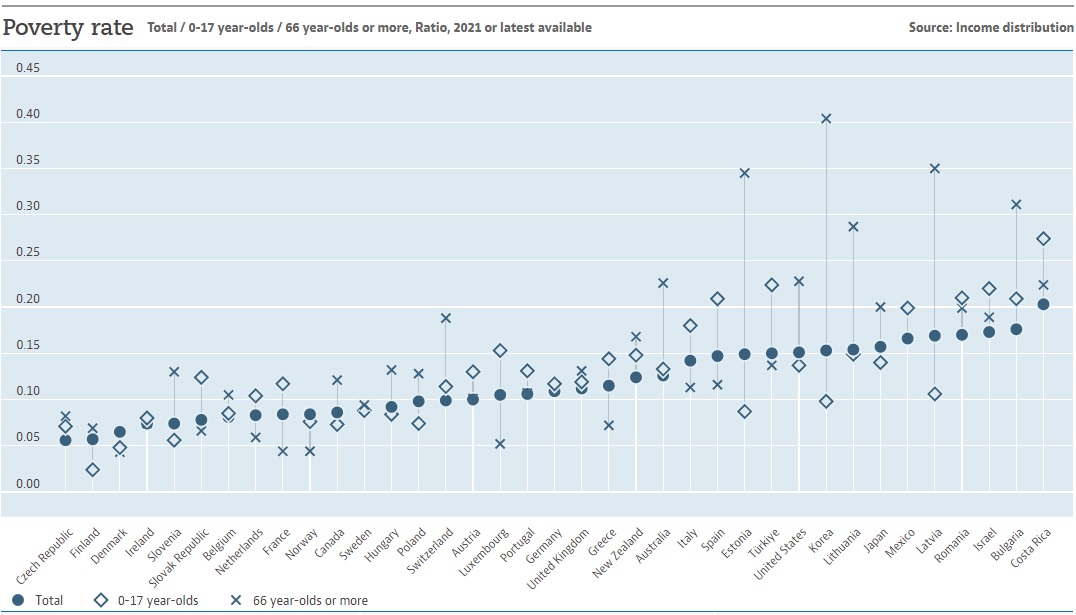

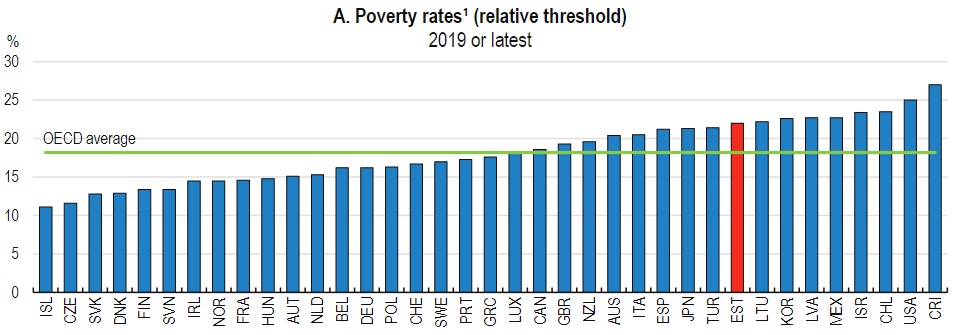

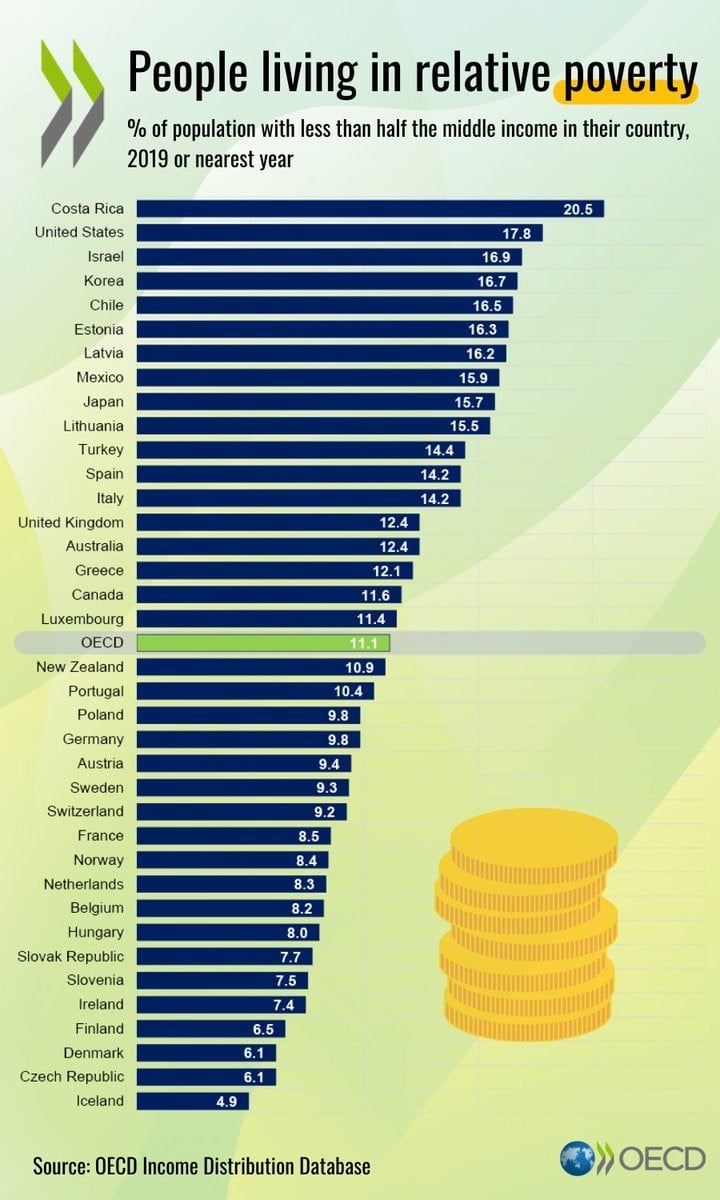

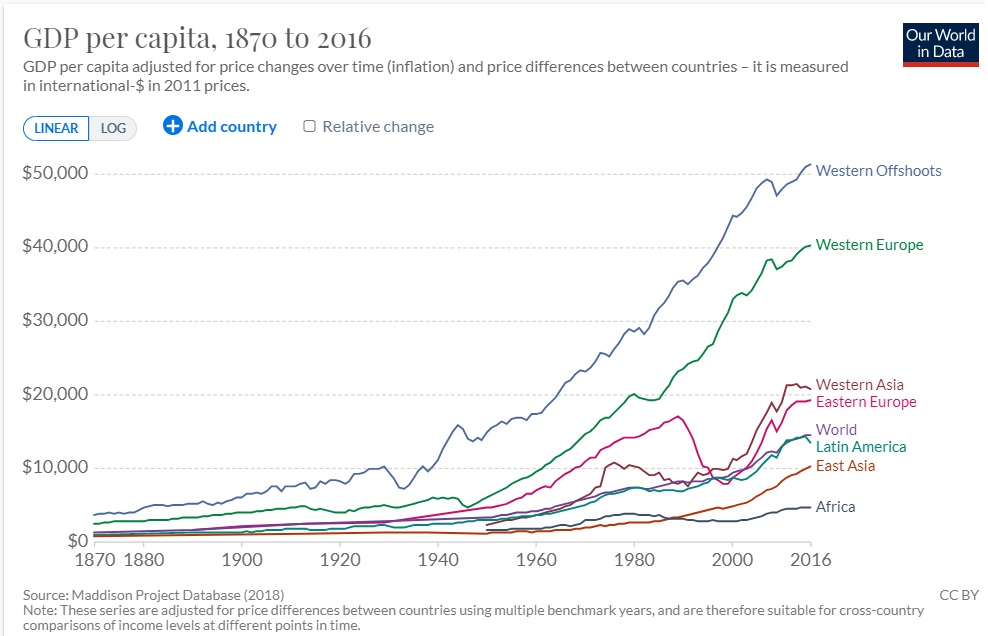

it will also fail future generations, lowering living standards and increasing the risk of poverty. …Already, America’s elderly suffer a far higher rate of poverty – defined as half the median income or lower – than their peers in other high-income countries. …the old-age poverty rate in the US is 23%, compared to about 15% in the United Kingdom, 12% in Canada, 4.4% in France, and just 3.1% in the Netherlands.

Since there are massive problems with Social Security, I agree with Ms. Ghilarducci that America’s retirement system isn’t working.

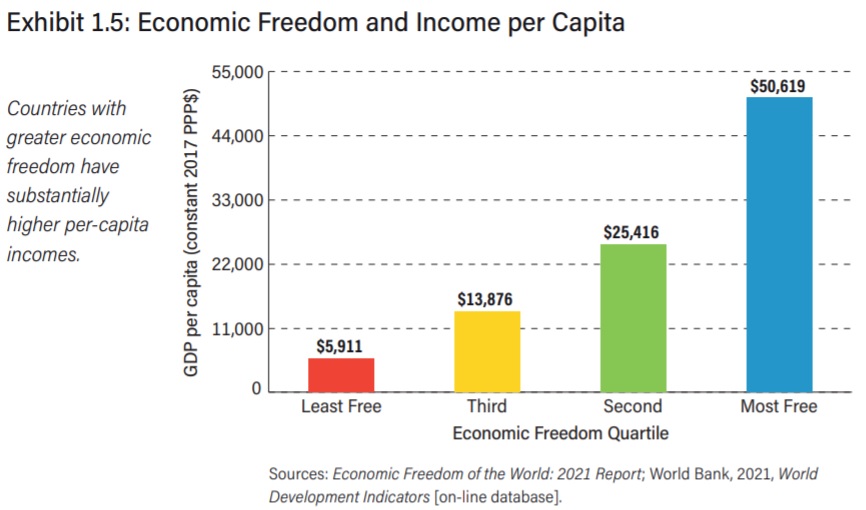

But her numbers on old-age poverty seem very strange. How can the poverty rate be much higher in the United States when the other countries she mentions have much lower living standards?

Notice, though, that she wrote that poverty is “defined as half the median income or lower.”

Notice, though, that she wrote that poverty is “defined as half the median income or lower.”

So if you were a millionaire and lived in a house with Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates, you would be poor based on this definition.

Needless to say, that’s crazy. Poverty should be a concrete number.

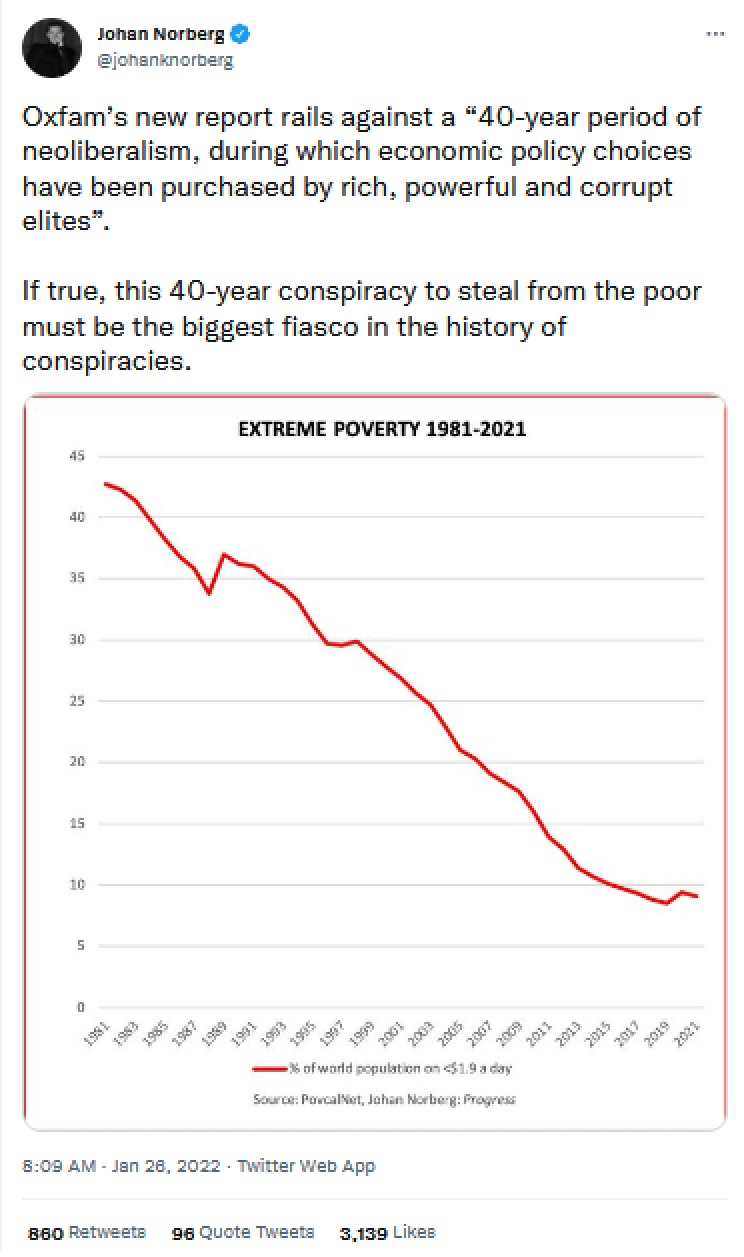

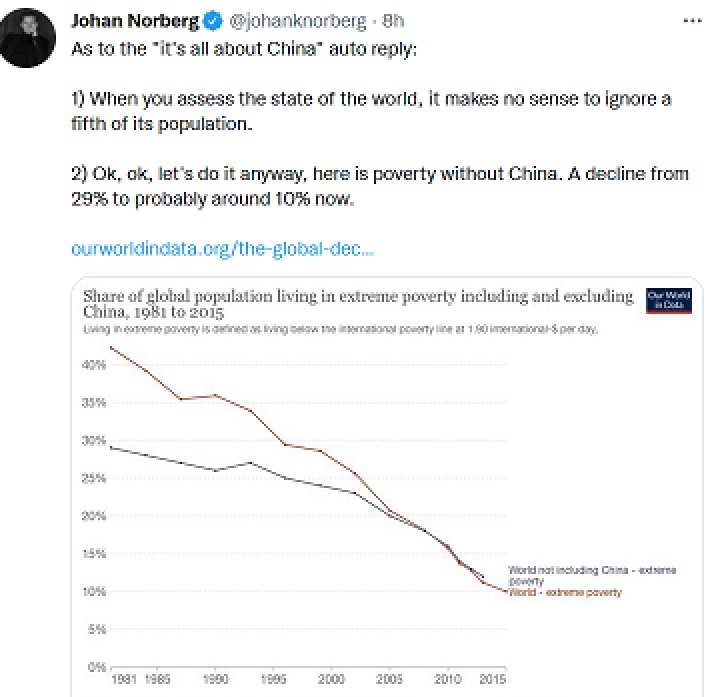

And it usually is. The World Bank (which is concerned about genuine material deprivation) measures poverty based on whether people are subsisting at very low levels, such as $1.90 per day. In the United States, the poverty rate is a specific calculation of what a household needs to subsist at a modest level.

Ms. Ghilarducci’s numbers, however, come from the left-leaning bureaucrats at the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

And they have a make-believe measure of poverty based on the distribution of income.

I’m not joking, if you go to their website, you will find these crazy numbers.

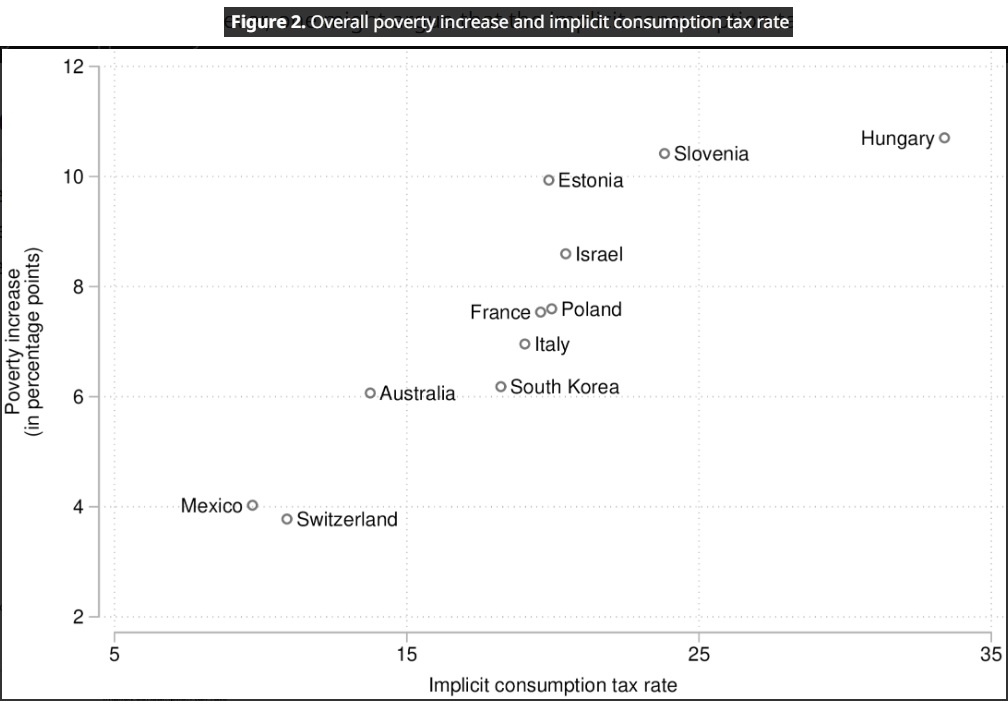

- There’s supposedly more old-age poverty in the United States than there is in countries such as Costa Rica, Greece, Italy, Poland, and Turkey.

- There’s supposedly more overall poverty in the United States than there is in countries such as Hungary, Mexico, Portugal, Slovenia, and Turkey.

These are garbage numbers, at least for the purpose of measuring poverty.

The average senior (or average person) in the United States is much better off than their counterparts in other countries.

So congratulations to Ms. Ghilarducci, who is now a member of the Poverty Hucksters Club.

P.S. In fairness to Ms. Ghilarducci, her article does make some good points about overall retirement policy. I’m sure we disagree on many things, but she favorably cites nations with private Social Security systems, such as Denmark and the Netherlands.