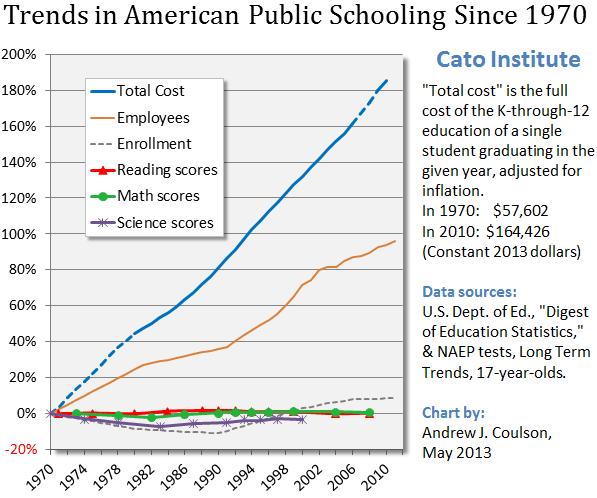

As part of National Education Week, I’ve looked at the deterioration of K-12 government schools and also explained why a market-based choice system would be a better alternative.

The good news is that we have a choice system for higher education. Students can choose from thousands of colleges and universities.

The bad news is that federal subsidies are making that system increasingly expensive and bureaucratic.

That’s today’s topic.

That’s today’s topic.

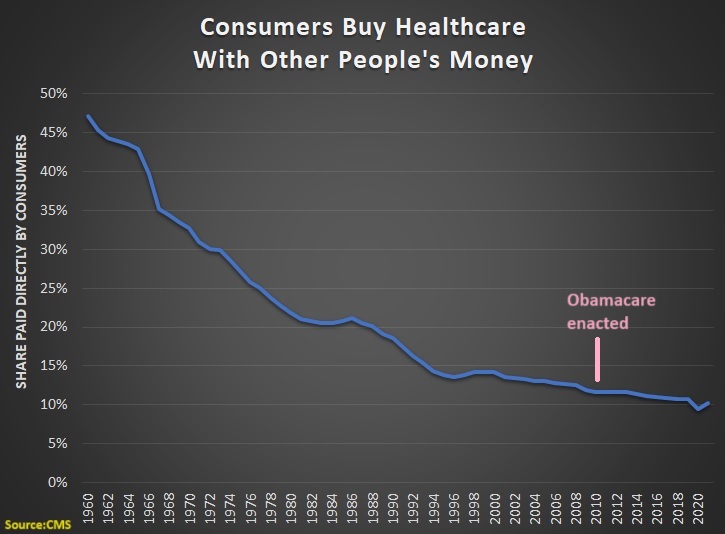

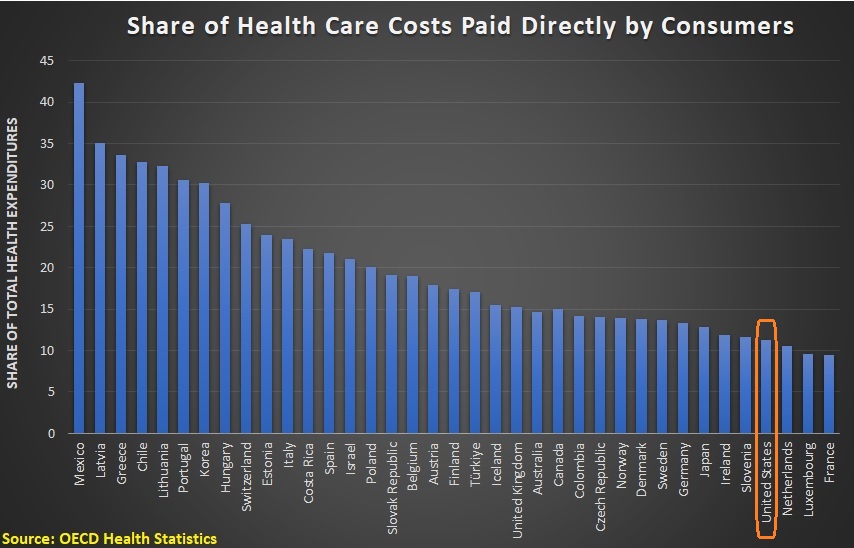

The underlying problem is “third-party payer,” which is a wonky term to describe what happens when students are buying education with money from somebody else. When this happens, they tend to not care about the price, which then makes it possible for colleges and universities to increase tuition so they become the real beneficiaries of the subsidies.

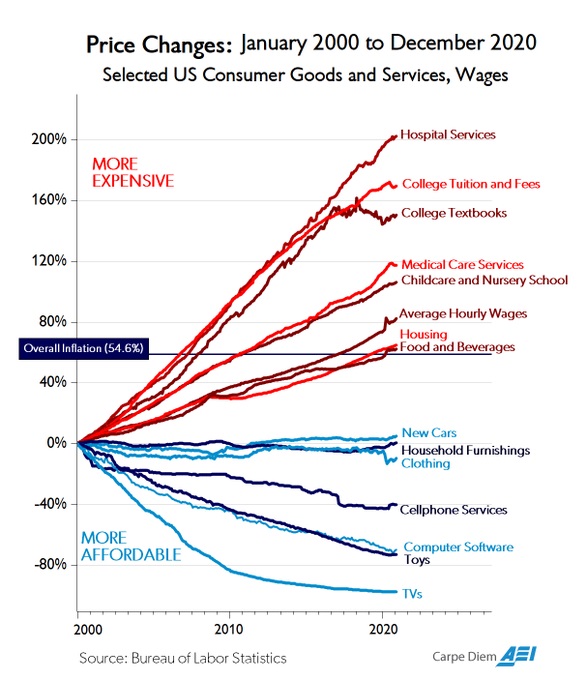

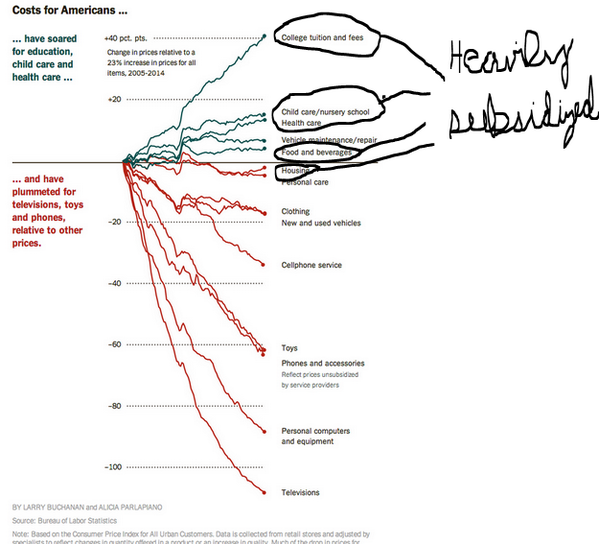

So nobody should be surprised that college costs are skyrocketing upwards, both in absolute terms and relative terms.

It’s a bubble, but one that probably won’t pop because of the ongoing stream of subsidies.

Jon Miltimore has a very good summary of the perverse incentives created by government.

Federal loans have made tuition far more expensive. Universities get paid up front—so whether students graduate, drop out, or default on the loan doesn’t matter. Departing students are easily replaced. Confident that students have access to cheap money (which can be expensive in the long run),  colleges have no incentive to control or cut back the prices of housing, tuition, fees, and meals. …The best solution is to get the federal government out of the loan business altogether. If universities themselves offered loans, incentives would push them toward controlling costs and maximizing student success after graduation. Another option is income share agreements, which allow potential employers or independent organizations to pay tuition in exchange for a percentage of the students’ future earnings. …When markets seem to falter—recent, painful examples include the student loan bubble and housing crisis—the culprit is often government intervening in a way that warps incentives.

colleges have no incentive to control or cut back the prices of housing, tuition, fees, and meals. …The best solution is to get the federal government out of the loan business altogether. If universities themselves offered loans, incentives would push them toward controlling costs and maximizing student success after graduation. Another option is income share agreements, which allow potential employers or independent organizations to pay tuition in exchange for a percentage of the students’ future earnings. …When markets seem to falter—recent, painful examples include the student loan bubble and housing crisis—the culprit is often government intervening in a way that warps incentives.

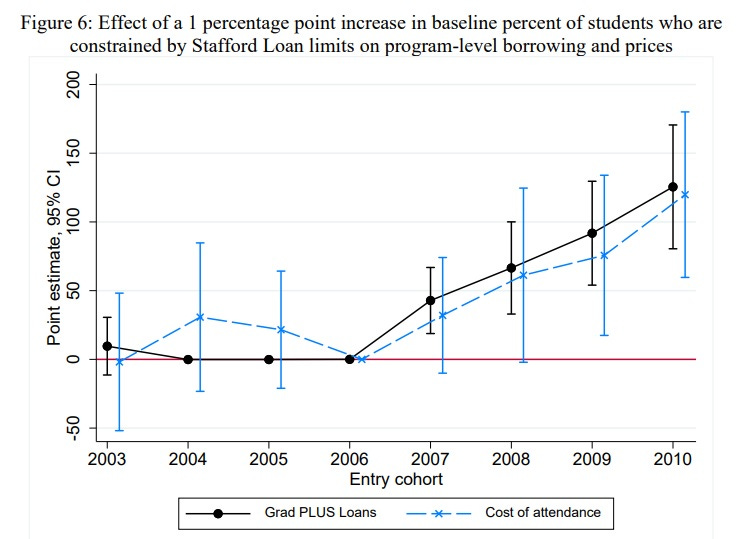

In a study for the Mercatus Center, Veronique de Rugy and Jack Salmon compile numbers and analyze studies.

The evidence broadly suggests that institutions of higher education are capturing need-based federal aid and responding to increased federal aid generosity by reducing institutional aid. …federal and state student aid funding expanding significantly over time, from just under $3 billion in 1970 to just under $160 billion in 2017. …Increased eligibility over time has led to a large and growing proportion of college students who receive federal financial aid. …there is a growing strand of economic literature examining the relationship between federal aid and tuition prices. …A study by Bradley Curs and Luciana Dar…finds that…institutions actually raise tuition levels and reduce their institutional aid when the state increases need-based awards. …A study by Stephanie Cellini and Claudia Goldin…finds that for comparable full-time nondegree programs in the same field over 2005–2009, institutions that are eligible for federal aid raised tuition by about 78 percent more than institutions that are ineligible. …Grey Gordon and Aaron Hedlund…develop a quantitative model for higher education to test explanations for the steep rise in college tuition between 1987 and 2010. …These results reveal that increased federal aid is responsible for more than doubling the cost of tuition over a 23-year period.

of college students who receive federal financial aid. …there is a growing strand of economic literature examining the relationship between federal aid and tuition prices. …A study by Bradley Curs and Luciana Dar…finds that…institutions actually raise tuition levels and reduce their institutional aid when the state increases need-based awards. …A study by Stephanie Cellini and Claudia Goldin…finds that for comparable full-time nondegree programs in the same field over 2005–2009, institutions that are eligible for federal aid raised tuition by about 78 percent more than institutions that are ineligible. …Grey Gordon and Aaron Hedlund…develop a quantitative model for higher education to test explanations for the steep rise in college tuition between 1987 and 2010. …These results reveal that increased federal aid is responsible for more than doubling the cost of tuition over a 23-year period.

Here’s a chart from the study showing the explosion of federal subsidies.

By the way, Paul Krugman actually thinks taxpayers have been “starving” higher education.

Let’s get back to exploring the analysis of more sensible economists. Professor Antony Davies and James Harrigan make two key points in their FEE column.

First, subsidies are producing consumers who don’t make sensible education purchases.

…total student debt in the United States passed the $1.5 trillion mark. …the total has been growing at around $80 billion per year. …Around 11 percent of student debt is either delinquent or in default, which is more than four times the delinquency rates for credit cards and residential mortgages. …the problem with making college “free…”  that a student must repay a college loan gives him tremendous incentive to at least consider what jobs he could obtain with the college education he must pay for after graduation. A student who is unencumbered by the need to repay a college loan faces little cost when choosing to major in something with little to no future value. …It’s well worth taking out tens of thousands of dollars in loans to pay for a degree that increases a student’s expected lifetime earnings by millions of dollars. But taking out tens of thousands in loans to pay for a degree that increases a student’s expected lifetime earnings by the same tens of thousands or less is, financially, a terrible investment.

that a student must repay a college loan gives him tremendous incentive to at least consider what jobs he could obtain with the college education he must pay for after graduation. A student who is unencumbered by the need to repay a college loan faces little cost when choosing to major in something with little to no future value. …It’s well worth taking out tens of thousands of dollars in loans to pay for a degree that increases a student’s expected lifetime earnings by millions of dollars. But taking out tens of thousands in loans to pay for a degree that increases a student’s expected lifetime earnings by the same tens of thousands or less is, financially, a terrible investment.

Here’s a chart from their article, which looks at the value of various majors.

Second, the problems are caused by bad government policy.

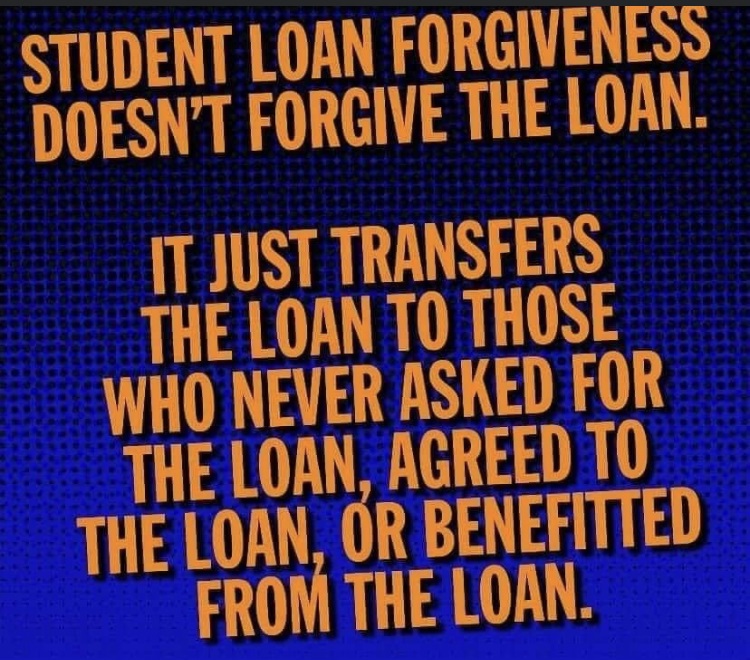

We are in the midst of a college loan bubble for almost all of the same reasons that, a decade ago, we found ourselves in the midst of a housing loan bubble. …In both bubbles, the government interfered in markets in two critical ways. First, the government stepped in as a lender. Second, it shielded private lenders from the consequences of making bad loans. …Making college “free” will simply double-down on the very problem we already face. With “free” college, not only will colleges not have to care whether students can repay their loans, but the students themselves will also not have to care. Meanwhile, taxpayers will be on the hook for the numerous imprudent decisions by both colleges and students. It will bring about the worst of all possible worlds.

Victor Davis Hanson of the Hoover Institution used to be a Classics Professor at California State University. So he’s well positioned to provide a then-now comparison.

Here’s what he experienced in his early years.

Overwhelmingly liberal and often hippish in appearance, American faculty of the early 1970s still only rarely indoctrinated students or bullied them to mimic their own progressivism. Rather, in both the humanities and sciences, students were taught the inductive method of evaluating evidence…  As an undergraduate and graduate student at hotbeds of prior 1960s protests at UC Santa Cruz and Stanford, I don’t think I had a single conservative professor. Yet there were few faculty members, in Western Civilization, history, classics, or mandatory general education science and math classes, who either sought to indoctrinate us with their liberal world view or punished us for remaining conservative. …Administrators in the 1960s and 1970s were relatively few. Most faculty saw administration as a temporary if necessary evil that took precious time away from teaching and research and so were admired for putting up with it. …Professors taught large loads—four or five classes a semester for California State University faculty. …The result was that both college tuition and room and board stayed relatively inexpensive.

As an undergraduate and graduate student at hotbeds of prior 1960s protests at UC Santa Cruz and Stanford, I don’t think I had a single conservative professor. Yet there were few faculty members, in Western Civilization, history, classics, or mandatory general education science and math classes, who either sought to indoctrinate us with their liberal world view or punished us for remaining conservative. …Administrators in the 1960s and 1970s were relatively few. Most faculty saw administration as a temporary if necessary evil that took precious time away from teaching and research and so were admired for putting up with it. …Professors taught large loads—four or five classes a semester for California State University faculty. …The result was that both college tuition and room and board stayed relatively inexpensive.

And here’s what it’s become.

What went wrong? …Politics increasingly infected courses as competence eroded—logical for faculty and students since the former required far less of the latter. Across the curriculum, race, class, and gender studies found their way into art, music, literature, philosophy and history classes. Deduction now replaced the old empiricism. Grades inflated… Universities emulated the ethos of loan sharks and shake-down businesses. The con was as simple as it was insidiously brilliant. Academic lobbyists pressed the government for billions in guaranteed student loans… The federal government-backed student loans. That guarantee greenlighted cash-flush universities to pay inter alia for diversity czars, assistant provosts of “inclusion,” and armies of woke aides and facilitators, to reduce teaching loads, and to open more race/class/gender “centers” on campus—by jacking up college costs higher than the rate of inflation. Student debt soared. …A new generation owes $1.5 trillion in student debt… One’s 20s are now redefined as the lost decade, as marriage, child-rearing, and home buying are put off, to the extent they still occur, into one’s 30s. …The result was reduced teaching, a bonanza of release time, administrative bloat, Club Med dorms, gyms, and student unions, and epidemics of highly paid but non-teaching careerist advisors, and counselors.

So what’s his solution?

Universities should be held responsible for repaying a large percentage of the loans they issued and yet in advance knew well could not and would not be repaid. The government should get out of the campus loan insurance business.

Amen.

As I said at the end of this recent TV interview, colleges and universities need to have some skin in the game.

Daniel Kowalski explains for FEE that government policy is causing ever-higher costs.

Student loans did not exist in their present form until the federal government passed the Higher Education Act of 1965, which had taxpayers guaranteeing loans made by private lenders to students. While the program might have had good intentions, it has had unforeseen harmful consequences. …Secured financing of student loans resulted in a surge of students applying for college.  This increase in demand was, in turn, met with an increase in price because university administrators would charge more if people were willing to pay it… According to Forbes, the average price of tuition has increased eight times faster than wages since the 1980s. …The government’s backing of student loans has caused the price of higher education to artificially rise…the current system of student loan financing needs to be reformed. Schools should not be given a blank check, and the government-guaranteed loans should only cover a partial amount of tuition. Schools should also be responsible for directly lending a portion of student loans so that it’s in their financial interest to make sure graduates enter the job market with the skills and requirements needed to get a well-paying job. If a student fails to pay back their loan, then the college or university should also share in the taxpayer’s loss.

This increase in demand was, in turn, met with an increase in price because university administrators would charge more if people were willing to pay it… According to Forbes, the average price of tuition has increased eight times faster than wages since the 1980s. …The government’s backing of student loans has caused the price of higher education to artificially rise…the current system of student loan financing needs to be reformed. Schools should not be given a blank check, and the government-guaranteed loans should only cover a partial amount of tuition. Schools should also be responsible for directly lending a portion of student loans so that it’s in their financial interest to make sure graduates enter the job market with the skills and requirements needed to get a well-paying job. If a student fails to pay back their loan, then the college or university should also share in the taxpayer’s loss.

All this government-fueled debt has real consequences. Three economists from the Federal Reserve found it hinders home ownership.

To estimate the effect of the increased student loan debt on homeownership, we tracked student loan and mortgage borrowing for individuals who were between 24 and 32 years old in 2005. Using these data, we constructed a model to estimate the impact of increased student loan borrowing on the likelihood of students becoming homeowners during this period of their lives. We found that a $1,000 increase in student loan debt (accumulated during the prime college-going years and measured in 2014 dollars) causes a 1 to 2 percentage point drop in the homeownership rate for student loan borrowers during their late 20s and early 30s. …According to our calculations, the increase in student loan debt between 2005 and 2014 reduced the homeownership rate among young adults by 2 percentage points. The homeownership rate for this group fell 9 percentage points over this period (figure 2), implying that a little over 20 percent of the overall decline in homeownership among the young can be attributed to the rise in student loan debt.

We found that a $1,000 increase in student loan debt (accumulated during the prime college-going years and measured in 2014 dollars) causes a 1 to 2 percentage point drop in the homeownership rate for student loan borrowers during their late 20s and early 30s. …According to our calculations, the increase in student loan debt between 2005 and 2014 reduced the homeownership rate among young adults by 2 percentage points. The homeownership rate for this group fell 9 percentage points over this period (figure 2), implying that a little over 20 percent of the overall decline in homeownership among the young can be attributed to the rise in student loan debt.

For those interested, here are some of their empirical findings.

By the way, I discussed the negative interaction of student debt and housing in the second half of this TV interview.

Professor Richard Vedder explains for the Wall Street Journal that this subsidized system has resulted in an environment in which neither students nor faculty work very hard.

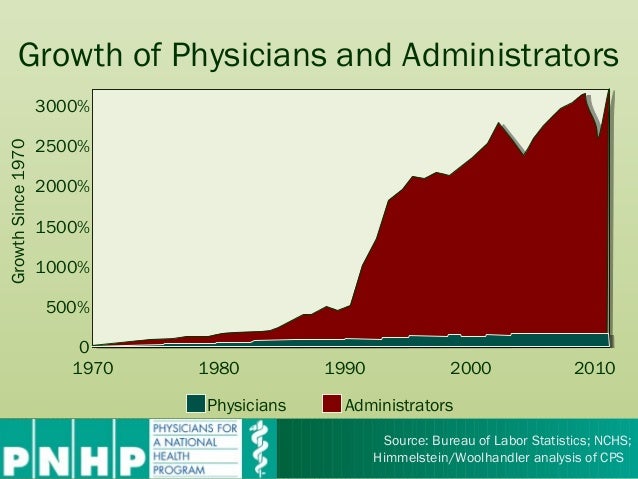

One reason college is so costly and so little real learning occurs is that collegiate resources are vastly underused. Students don’t study much, professors teach little, few people read most of the obscure papers the professors write, and even the buildings are empty most of the time. …Surveys of student work habits find that the average amount of time spent in class and otherwise studying is about 27 hours a week. The typical student takes classes only 32 weeks a year, so he spends fewer than 900 hours annually on academics—less time than a typical eighth-grader… As economists Philip Babcock and Mindy Marks have demonstrated, students in the middle of the 20th century spent nearly 50% more time—around 40 hours weekly—studying. They now lack incentives to work very hard, since the average grade today—a B or B-plus—is much higher than in 1960… Sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa have demonstrated, using the Collegiate Learning Assessment, that the typical college senior has only marginally better critical reasoning and writing skills than a freshman. Federal Adult Literacy Survey data, admittedly somewhat outdated, shows declining literacy among college grads in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. …the typical professor is in class around one-third fewer hours than his 1965 counterpart. …The litany of underused resources goes on. In 1970 at a typical university there were perhaps two professors for each administrator. Today, there are usually more nonteaching administrators than professors.

so he spends fewer than 900 hours annually on academics—less time than a typical eighth-grader… As economists Philip Babcock and Mindy Marks have demonstrated, students in the middle of the 20th century spent nearly 50% more time—around 40 hours weekly—studying. They now lack incentives to work very hard, since the average grade today—a B or B-plus—is much higher than in 1960… Sociologists Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa have demonstrated, using the Collegiate Learning Assessment, that the typical college senior has only marginally better critical reasoning and writing skills than a freshman. Federal Adult Literacy Survey data, admittedly somewhat outdated, shows declining literacy among college grads in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. …the typical professor is in class around one-third fewer hours than his 1965 counterpart. …The litany of underused resources goes on. In 1970 at a typical university there were perhaps two professors for each administrator. Today, there are usually more nonteaching administrators than professors.

Unfortunately, many politicians respond to these government-caused problems by proposing even more government.

That’s what Hillary Clinton did in 2016 and it’s what politicians – most notably Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders – are doing for 2020.

But that will make a bad situation even worse.

Paul Boyce, writing for FEE, explains that free college will lower standards and make college degrees relatively meaningless.

…college enrollment rates reached more than 40 percent in 2017. Of those, nearly one in three (31 percent) drop out entirely. Why should the average taxpayer subsidize this? …If college is free, it is likely that this rate will increase further. Students won’t have any skin in the game because they won’t be picking the tab up at the end. This effects efficient decisionmaking. In France, for example, the dropout rate is as high as 50 percent. …Government has a track record of underfunding. …This is demonstrated in France, which runs a “free” system. Its universities are heavily underfunded and unable to satisfy student enrollment. …As college enrollment has increased, standards have fallen to accommodate for this. …it defeats the goal of creating a well-educated workforce. …it dilutes the importance and value of a degree. …Undergraduate degrees will become the norm, and the financial return will become negligible.

This effects efficient decisionmaking. In France, for example, the dropout rate is as high as 50 percent. …Government has a track record of underfunding. …This is demonstrated in France, which runs a “free” system. Its universities are heavily underfunded and unable to satisfy student enrollment. …As college enrollment has increased, standards have fallen to accommodate for this. …it defeats the goal of creating a well-educated workforce. …it dilutes the importance and value of a degree. …Undergraduate degrees will become the norm, and the financial return will become negligible.

And the experience of other nations isn’t a cause for optimism.

Andrew Hammel, an American who taught for many years at a German university, is not overly impressed by that nation’s free-tuition regime.

…in their early teen years, the brightest German students are sent to the most prestigious form of German high school, the Gymnasium. Currently, over 50 percent of German students earn this privilege (this number has jumped in the last 30 years, prompting charges of grade inflation). Gymnasium graduates with reasonable grades are guaranteed a place in a German university; there is no entrance exam. 95 percent of German students attend public universities,  where they are charged fees, but not formal tuition. All professors at public universities are civil servants. …Supporters of the tuition-free system note that 65 percent of Germans say university should be tuition-free, “even if this means the quality of education is slightly worse.” …The system also gives students extra freedom: you can study art history or sociology, knowing that you won’t be hounded by creditors if you later find only spotty employment. …one-third of all students who enroll in German universities never finish. A recent OECD study found that only 28.6 percent of Germans aged between 25 and 64 had a tertiary education degree… German universities punch below their weight in international rankings… Gather any group of German professors, and talk will immediately turn to the burgeoning bureaucracy which distracts them from teaching and research. …Americans who teach ordinary classes in Germany find average German students somewhat less motivated than their dues-paying American counterparts. The top third of motivated students would succeed anywhere, and the bottom third, as we have seen, drop out.

where they are charged fees, but not formal tuition. All professors at public universities are civil servants. …Supporters of the tuition-free system note that 65 percent of Germans say university should be tuition-free, “even if this means the quality of education is slightly worse.” …The system also gives students extra freedom: you can study art history or sociology, knowing that you won’t be hounded by creditors if you later find only spotty employment. …one-third of all students who enroll in German universities never finish. A recent OECD study found that only 28.6 percent of Germans aged between 25 and 64 had a tertiary education degree… German universities punch below their weight in international rankings… Gather any group of German professors, and talk will immediately turn to the burgeoning bureaucracy which distracts them from teaching and research. …Americans who teach ordinary classes in Germany find average German students somewhat less motivated than their dues-paying American counterparts. The top third of motivated students would succeed anywhere, and the bottom third, as we have seen, drop out.

I’ll close with an observation about inefficiency in higher education.

Here’s a chart I shared a few years ago. I’m sure the problem is even worse today.

The bottom line is that student debt, administrative bloat, and expensive tuition are all predictable consequences of federal subsidies.

P.S. If you’re worried about political correctness in higher education (and you have the appropriate subscriptions), I recommend this column in the Wall Street Journal and this George Will column in the Washington Post.

P.P.S. Here’s a video interview with Richard Vedder about high costs and inefficiency in higher education. And I also recommend this video explanation by Professor Daniel Lin.

P.P.P.S. It also turns that all these subsidies have a negative correlation with private-sector employment.

Read Full Post »

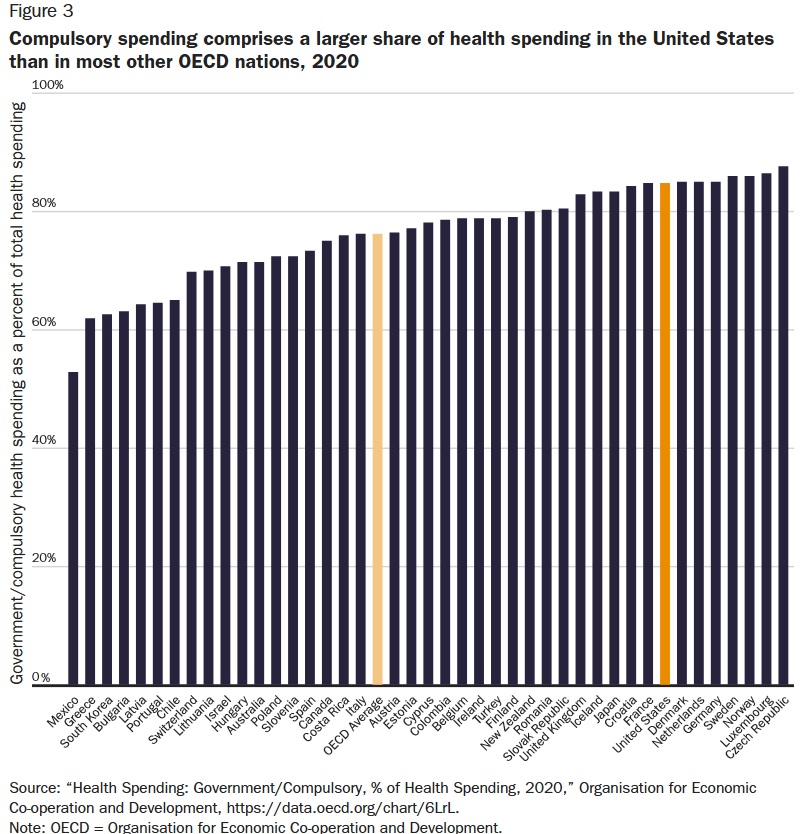

All these years later, we still haven’t found the magic money pot. …Obamacare contained a lot of elements that were expected to realize significant cost savings while actually improving the quality of care. …What this demonstrates is how hard it is to actually change the system in ways that generate major savings. …the wonks hunting for magic pots of money have mostly turned out to be chasing rainbows.