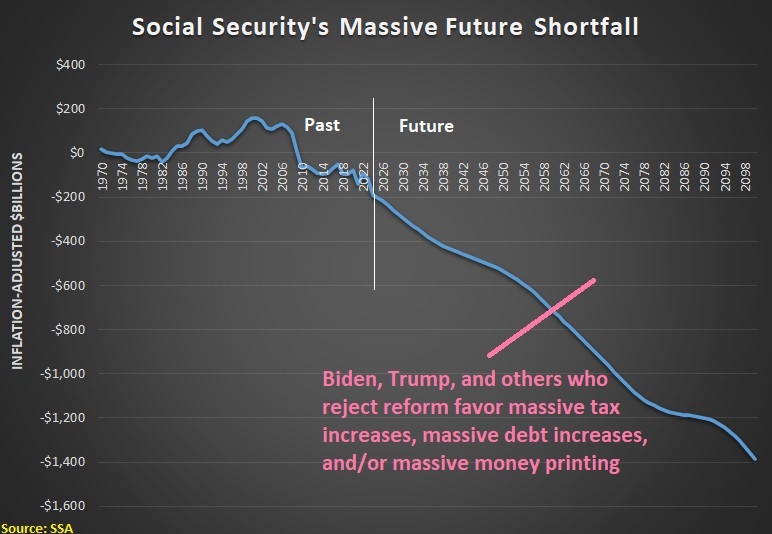

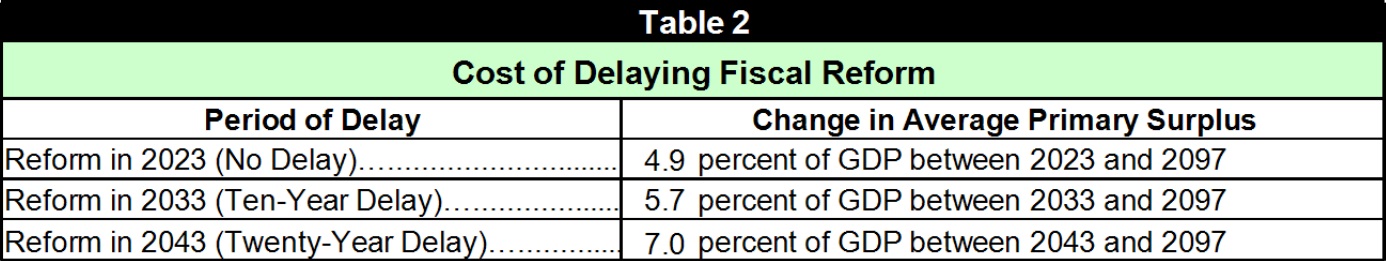

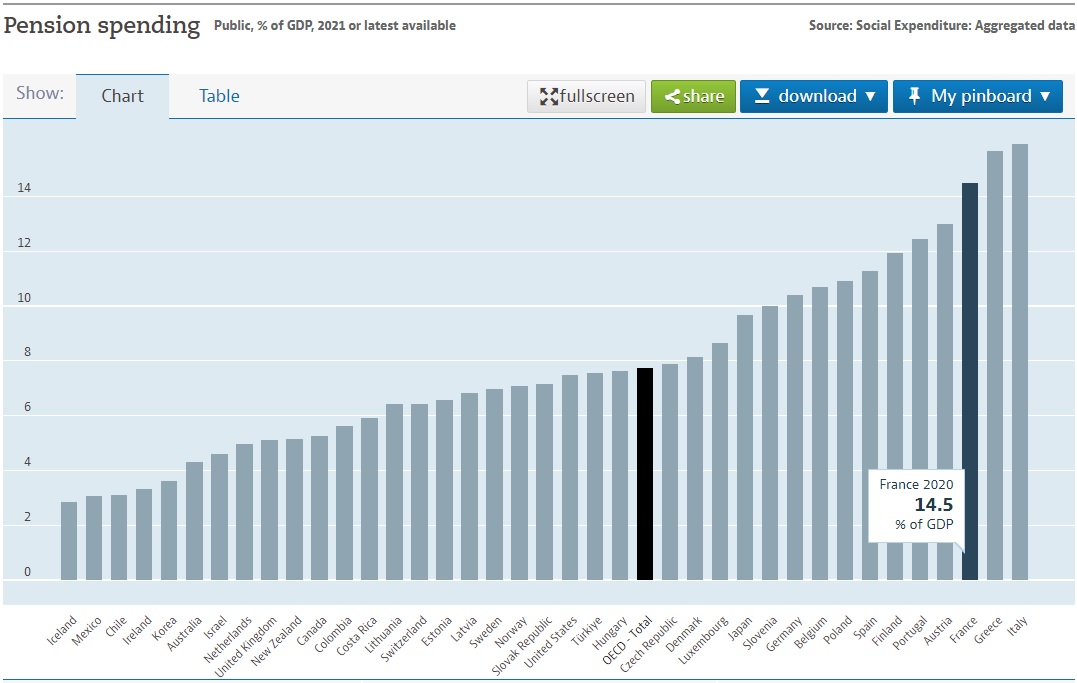

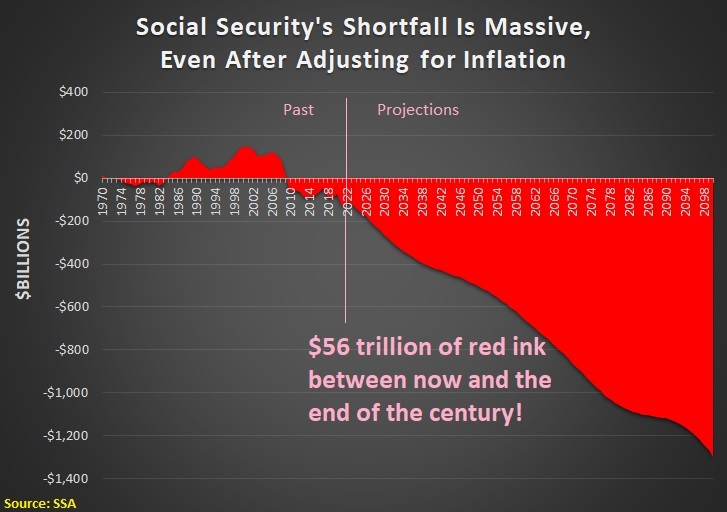

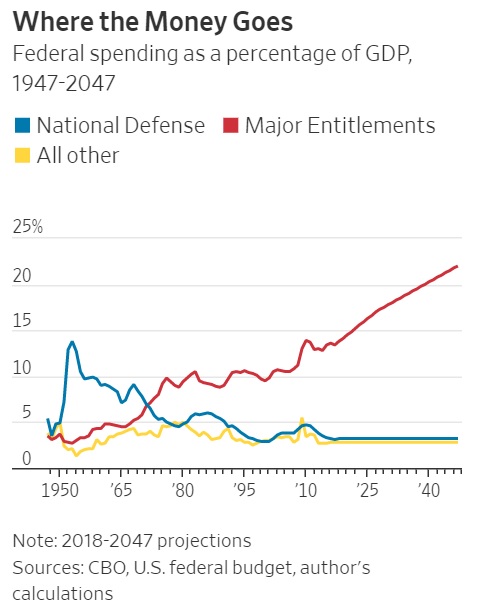

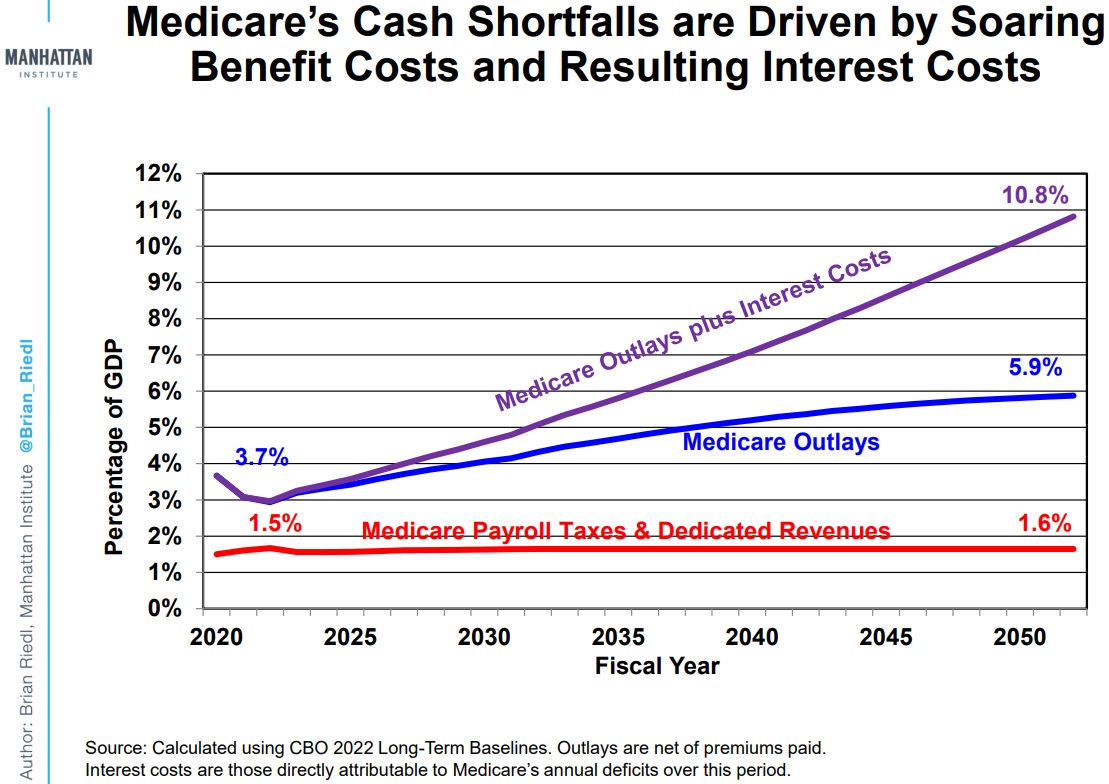

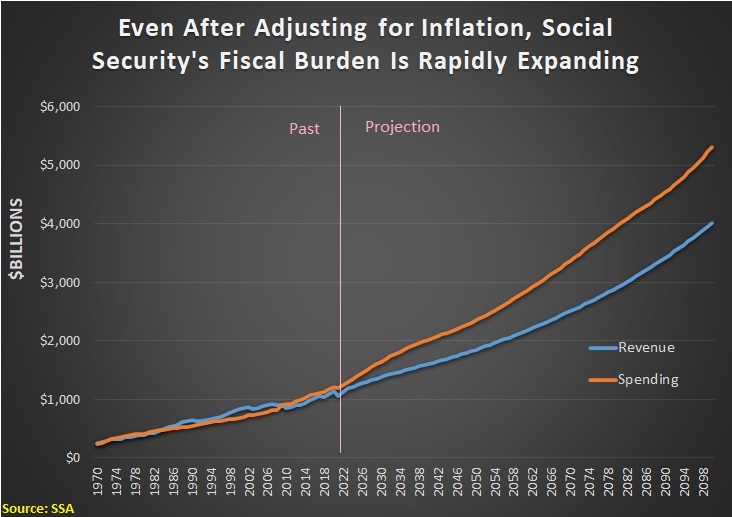

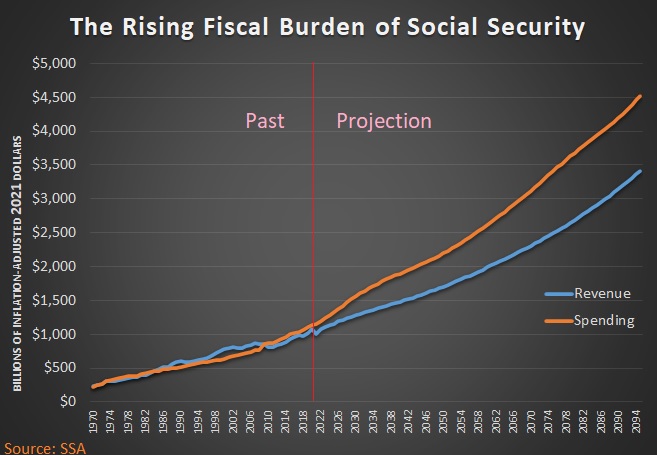

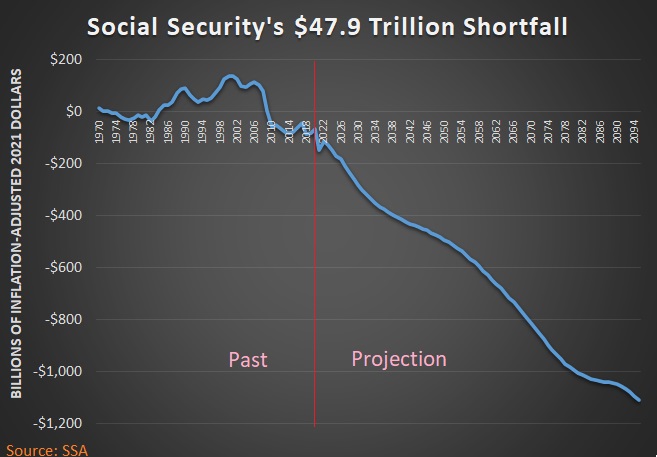

When the Social Security Administration released its annual Trustees’ Report last week, I crunched the numbers to show that the fiscal burden of the program is projected to dramatically increase.

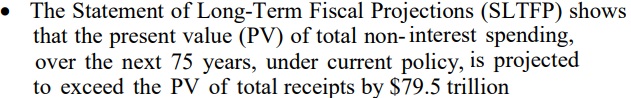

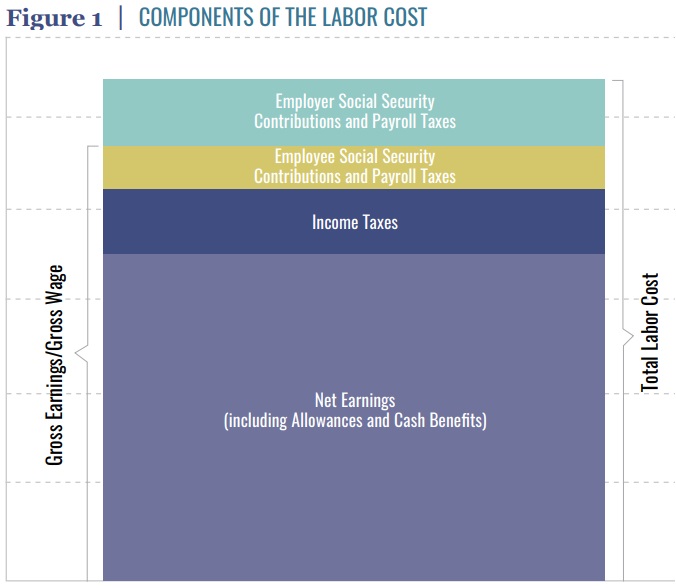

Payroll taxes are going to climb rapidly, but spending will grow even faster. As a result, the program’s long-run shortfall is now $61.7 trillion.

Payroll taxes are going to climb rapidly, but spending will grow even faster. As a result, the program’s long-run shortfall is now $61.7 trillion.

That’s a lot of money, even by the standards of our fiscally incontinent masters in Washington.

The good news is that the program’s fiscal problems are getting some attention.

The bad news is that some of the analysis is sloppy.

For instance, Michelle Singletary, who writes about personal finance for the Washington Post, has a column about Social Security.

Social Security is a critical program for millions of Americans, yet there is so much that people don’t understand. …Without any change in current law,

the Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance (OASDI) trust funds combined are projected to have enough revenue — including current reserves — to pay 100 percent of scheduled benefits on a timely basis only until 2035. …This news rightly rattles a lot of people. It also leads to fearmongering. …As the retirement program faces a funding shortfall, it’s time to retire…five common myths.

Debunking myths is a good thing.

And what she wrote about two of the myths (dealing with when to retire and whether politicians are in the system) is accurate.

Unfortunately, the other three require elaboration/correction.

Here’s what she wrote, followed by my analysis.

Myth No. 1: Social Security is, or will be, ‘bankrupt’: Social Security will not run out of money. The program is financed by payroll taxes, so as long as workers pay into the system, money will always come in. …It’s the Social Security Trust Funds’ reserves that are projected to become depleted. …The Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program, which pays retirement and survivor benefits, will be able to pay 100 percent of benefits until 2033.Even if Congress fails to act, there will be enough projected income coming in to cover 79 percent of scheduled benefits.

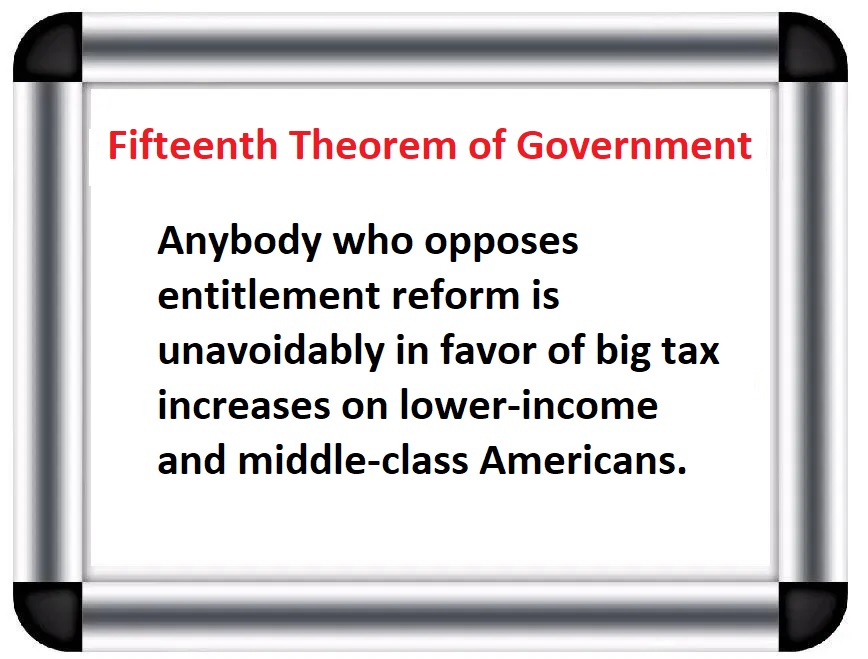

Reality: I’m baffled that she wrote that “Social Security will not run out of money” and then a few sentences later admitted that there will only be enough income “to cover 79 percent of scheduled benefits.” Makes me wonder about her definition of bankruptcy. I’ll simply note that if Social Security was a private pension system providing annuities, the government would shut it down and probably arrest the people in charge.

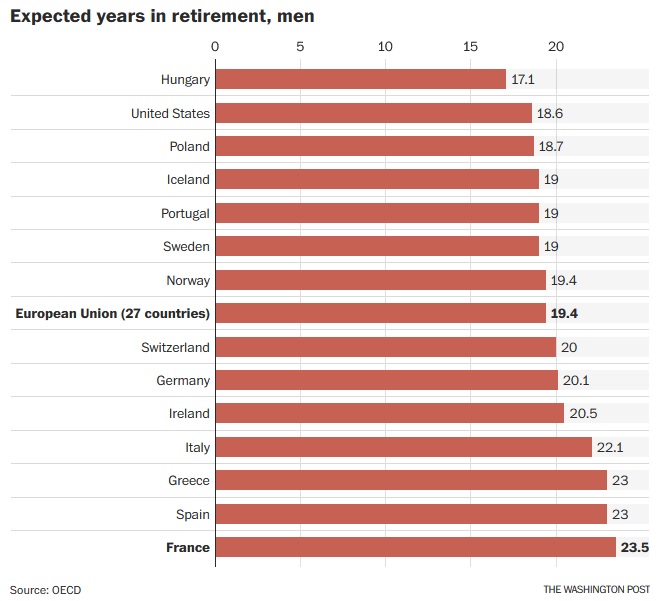

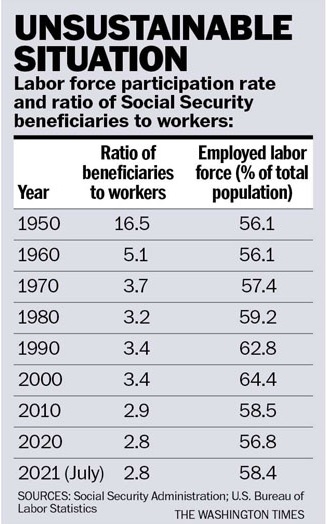

Myth No. 2: Young adults won’t benefit from Social Security: 42 percent of adults ages 18 to 29 are “extremely worried” that Social Security will not be available when they become eligible. …Some proposed changes to the program could affect younger workers, such as raising the age when full benefits kick in. For anyone born in 1960 or later, full retirement benefits are payable at age 67. Because so many Americans rely on Social Security, it’s not going anywhere.

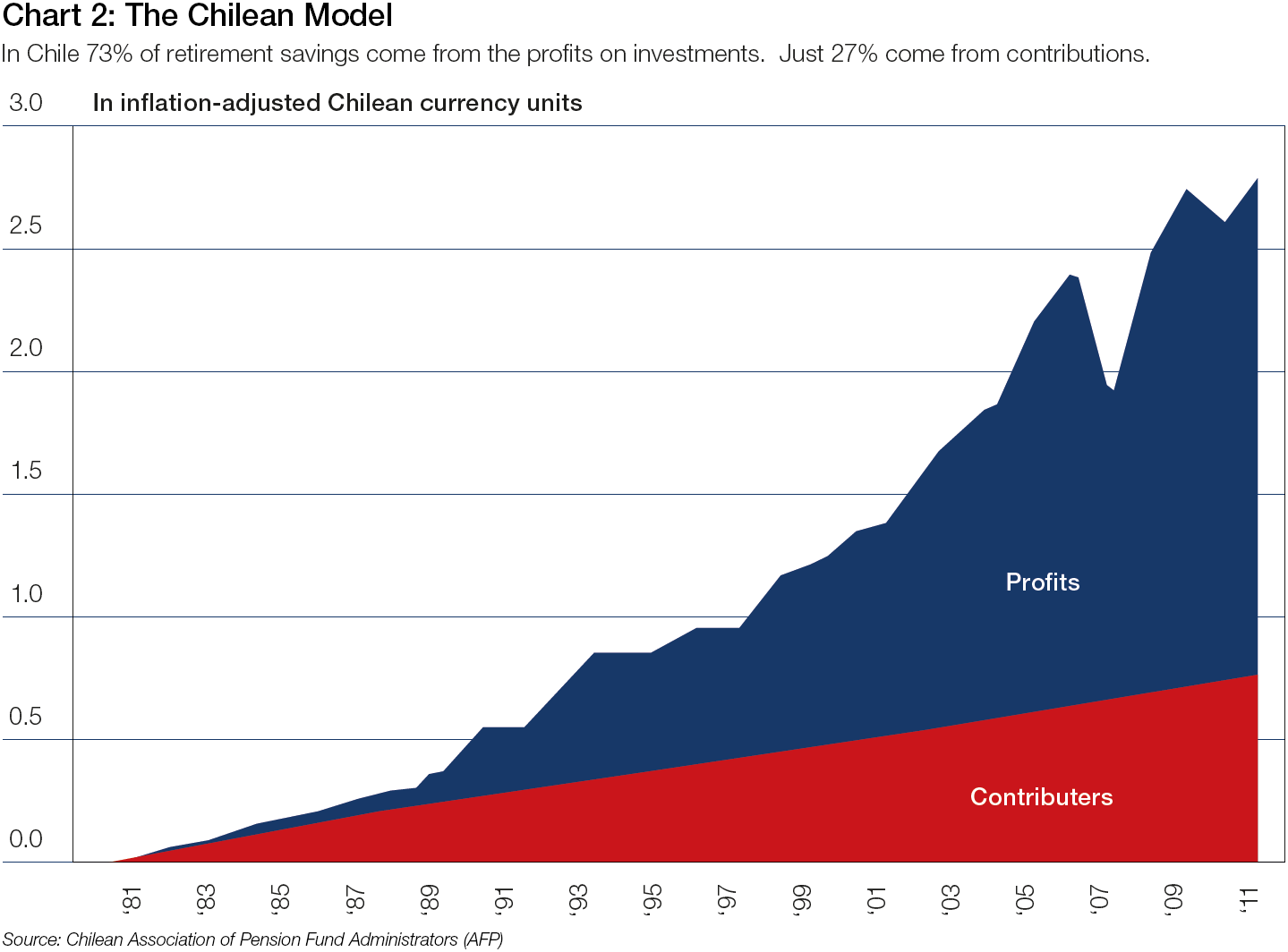

Reality: Once again, the author must be using some strange definitions. Yes, today’s young people will receive money from Social Security, so we can consider that a benefit. But the real issue is whether they receive net benefits. The answer is no when you consider all their payroll taxes. And the answer is a very emphatic no if you compare what they are promised from Social Security compared to what they would get if they instead had private retirement accounts.

Myth No. 4: The federal government has raided the Social Security Trust Funds: Think of the Social Security Trust Funds like your savings account… By law, every dollar of income coming into the Social Security Trust Funds is invested in interest-bearing securities backed by the full faith and credit of the United States… Yes, that money has been spent for other government needs, but that does not mean Social Security gets worthless IOUs… The securities held by the trust funds have always been honored, as have all other Treasury securities.

Reality: Fortunately, I don’t need to debunk her analysis. I can simply cite what the Clinton Administration wrote about the so-called Trust Fund back in 1999 (see page 337).

These balances are available to finance future benefit payments and other trust fund expenditures–but only in a bookkeeping sense. …They do not consist of real economic assets that can be drawn down in the future to fund benefits. Instead, they are claims on the Treasury, that, when redeemed, will have to be financed by raising taxes, borrowing from the public, or reducing benefits or other expenditures.

As I noted back in 2016, “the Trust Fund is like putting IOUs to yourself in a college fund. When it’s time for junior to start his freshman year, you’ll have to find the money to cash those IOUs.”

Since Ms. Singletary writes about personal finance, she presumably understands that’s not a smart strategy for a family. So I’m puzzled why she thinks it’s a good approach for a government.

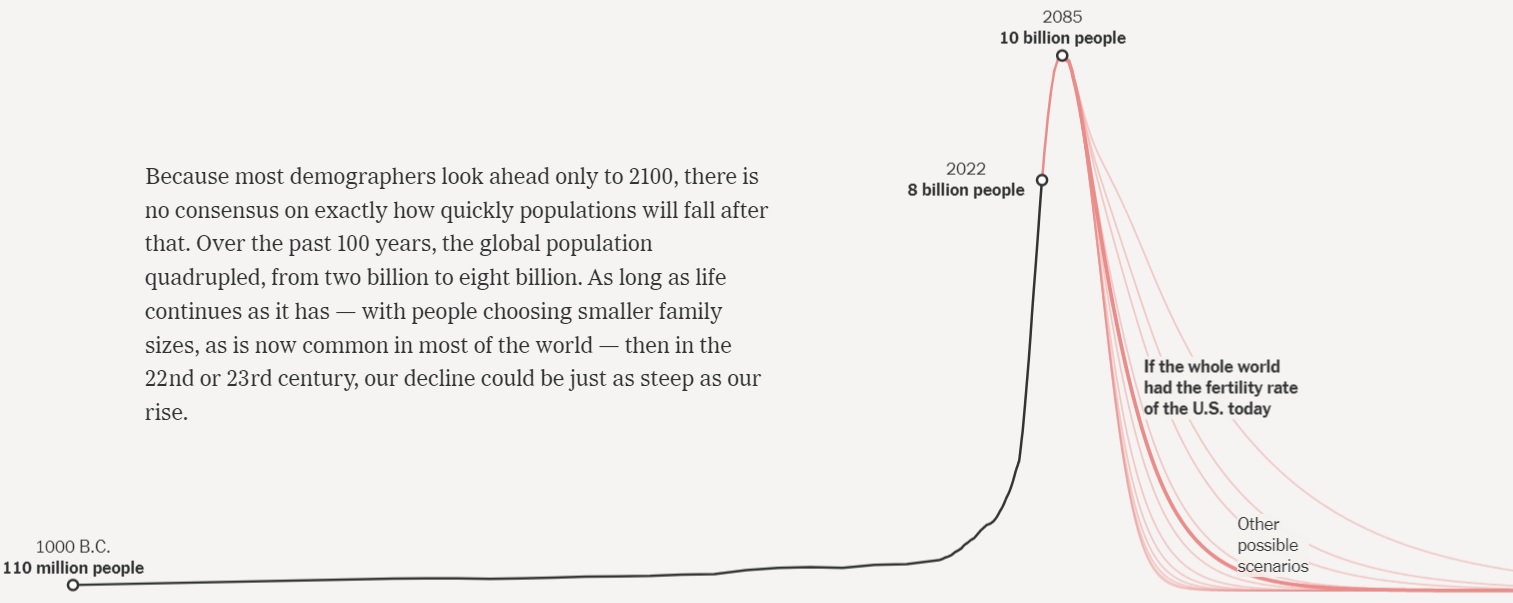

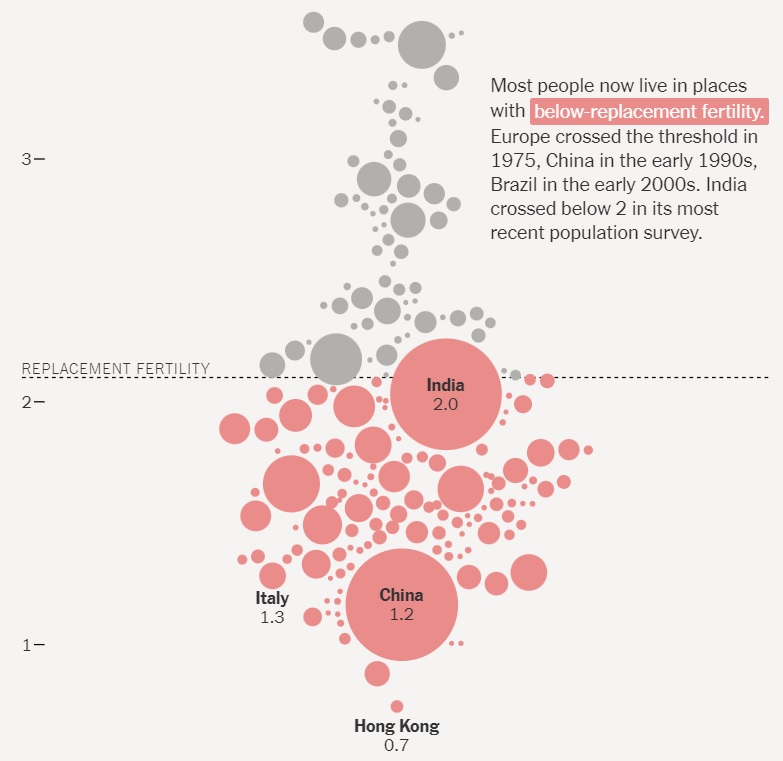

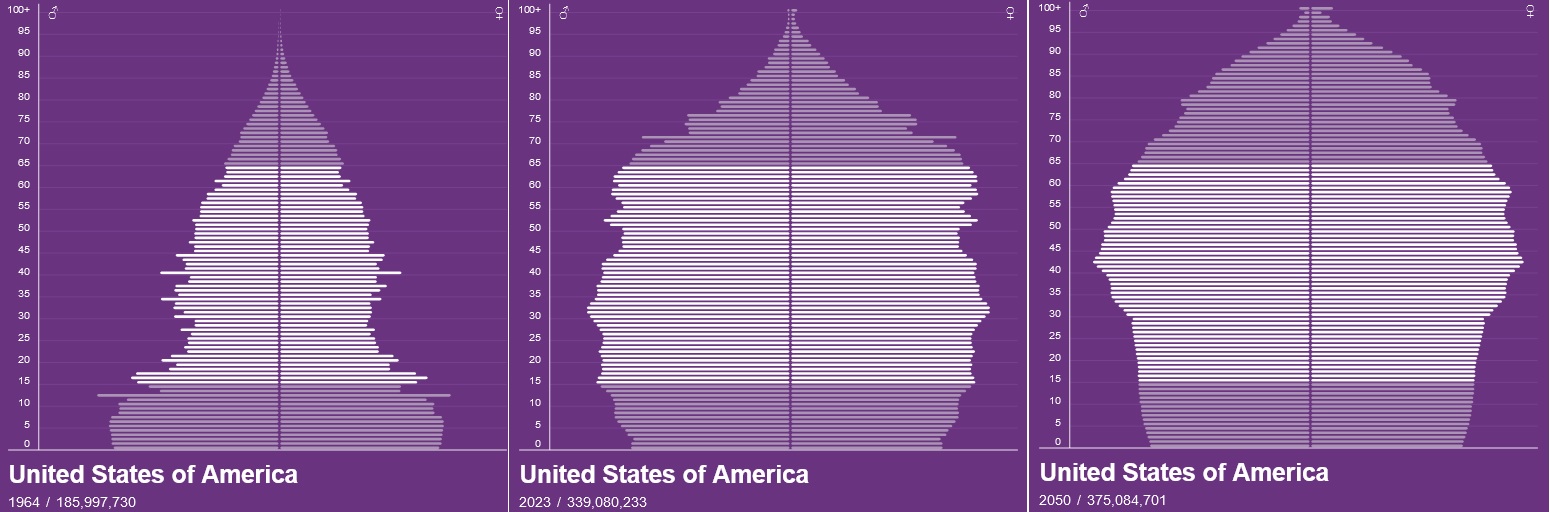

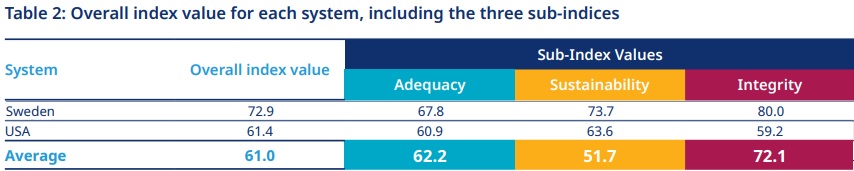

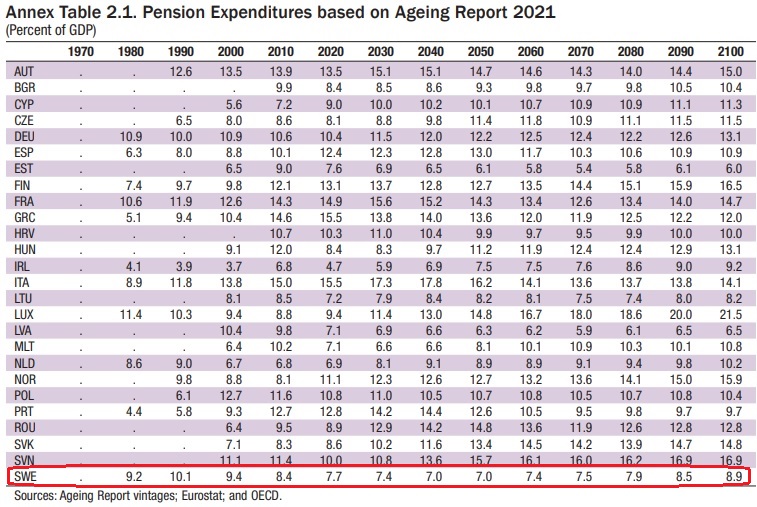

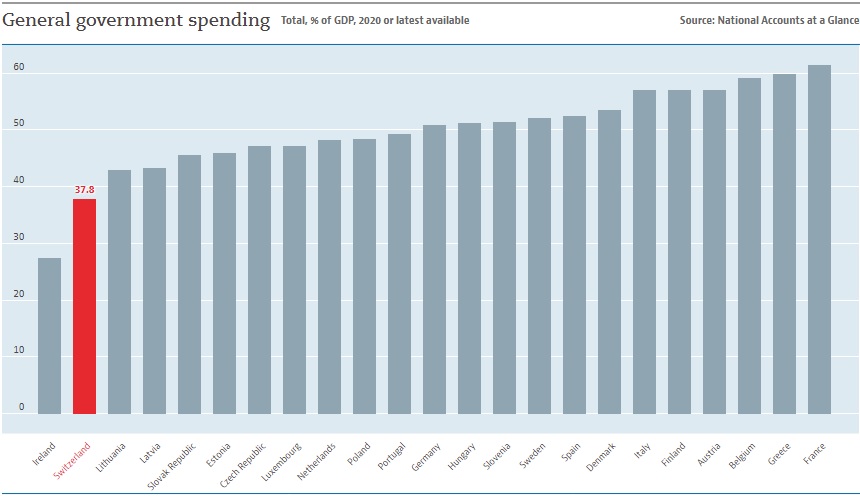

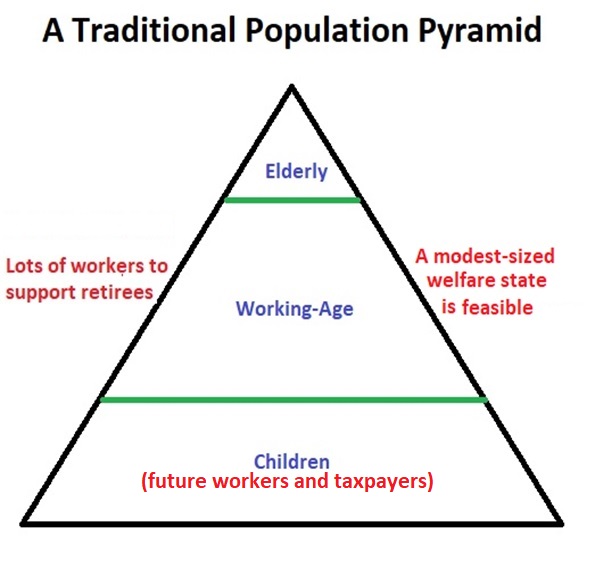

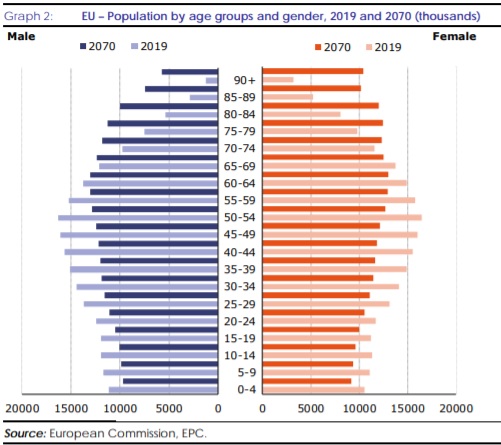

I’ll close by expressing disappointment that both Biden and Trump favor the status quo on Social Security, which is a recipe for massive future tax increases, massive future debt increases, and/or massive future money printing. Too bad they are unwilling to learn from Australia, Chile, Switzerland, Hong Kong, Netherlands, the Faroe Islands, Denmark, Israel, and Sweden, all of which show that it is possible to fully or partially replace debt-based systems with savings-based systems.