I had mixed feeling when I spoke yesterday in Bratislava, Slovakia, as part of the 2018 Free Market Road Show.

Last decade, Slovakia was a reform superstar, shaking off the vestiges of communism with a plethora of very attractive policies – including a flat tax, personal retirement accounts, and spending restraint.

As Marian Tupy explained last year, “…in 1998, Slovaks kicked out the nationalists and elected a reformist government, which proceeded to liberalise the economy, privatise loss-making state-owned enterprises  and massively improve the country’s business environment. …In 2005, the World Bank declared Slovakia the “most reformist” country in the world.”

and massively improve the country’s business environment. …In 2005, the World Bank declared Slovakia the “most reformist” country in the world.”

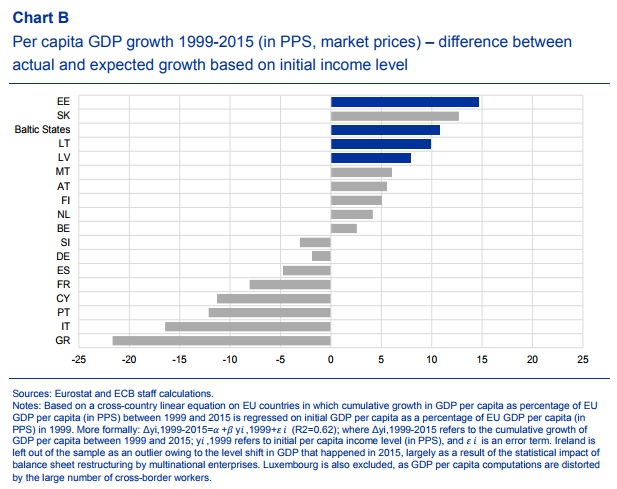

And these policies paid off. According to research from both Europe and the United States, Slovakia has enjoyed reasonably strong growth that has resulted in considerable “convergence” to western living standards.

But in recent years, Slovakia has gradually moved in the wrong direction, which means I have good and bad memories of my visits.

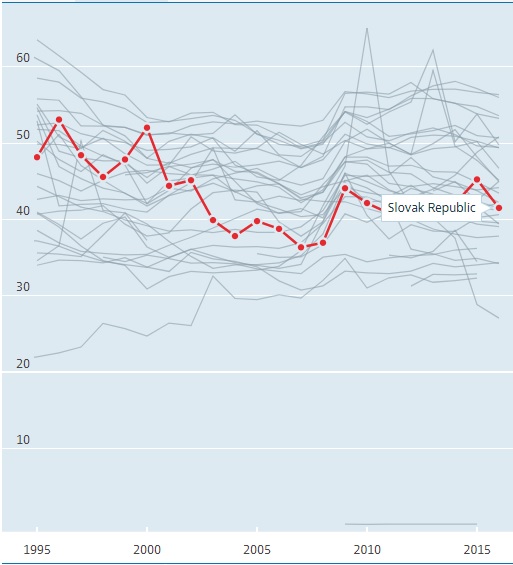

The nation’s strong rise and subsequent slippage can be seen in the data from Economic Freedom of the World.

The drop may not seem that dramatic. And in terms of Slovakia’s absolute score, it “only” fell from 7.63 to 7.31.

But what really matters (as I explained last year when writing about Italy) is the relative score. And if you take a closer look at the data, Slovakia has dropped in the rankings from #20 in 2005 to #53 in 2015.

This relative decline is not good news for a nation that wants to compete for jobs and investment. Moreover, I’m not the only one to be worried about slippage in Slovakia.

Jan Oravec is similarly concerned about a gradual erosion of competitiveness in his country.

…the World Economic forum, which compares the competitiveness of 140 countries around the world, Slovakia ranked 67th. …If we…look at the long-term evolution of the Slovak economy’s competitiveness not only in this,

but in other rankings, we realize…a tragic story of a dramatic decline in our competitiveness. Let us start by looking back at our previous scores: In 2000, we ranked 38th, while in 2010 we painfully fell to 60th – today we hold the aforementioned 67th place. …If we take a look at the evolution of Slovakia’s situation from the last 10 years, we come to the conclusion that there has been a significant drop in the ranking of our competitiveness. While 10 years ago we usually ranked in the top third or quarter of the ranked countries, today we usually rank in the bottom half… An explanation to this negative trend is twofold: Other countries have been improving while our business environment has been worsening, or stagnating at best.

There are three glaring examples of slippage in Slovakia.

- The first is that the flat tax was undone in 2012.

- The second is that the private social security system was weakened.

- The third is an erosion of fiscal discipline.

To be sure, it’s not as if Slovakia went hard left. The top tax rate under the new “progressive” system is 25 percent. And as I noted last month, that means high-income workers in Slovakia are still treated rather well compared to their counterparts in other industrialized nations.

And the leftist government in Slovakia weakened – but did not completely reverse – personal retirement accounts.

Jan Oravec explains the good reform that was adopted last decade.

During 2003 two main legislative acts – the Social Insurance Act and the Old-Age Pension Savings Act – were prepared by the reform team.

…Prior to reform Slovaks were obliged to pay to the PAYGO system contributions of 28.75 % of their gross wages, and the system promised in exchange to pay an average old-age benefit amounting to 50 % of gross wages. The reform allowed workers to redirect a significant part of their contributions, 9 % of gross wage, to their personal retirement accounts.

Under current law, however, the amount that workers are allowed to place in private accounts has been reduced. Moreover, the government is forcing the accounts to invest in government bonds, which means workers will earn sub-par returns. These are bad changes, but at least personal accounts still exist.

Even the bad news on government spending isn’t horrible news. As you can see from this OECD data, the spending burden (measured as a share of GDP) has climbed to a higher plateau in recent years, wiping out some of the gains that were achieved thanks to a period of strong restraint early last decade. That being said, Slovakia is still in better shape than many other industrialized nations.

So where does Slovakia go from here?

That’s not clear. The Prime Minister that imposed some of the bad policies recently was forced out of office by scandal, but his replacement isn’t any better and there’s not another election scheduled until 2020.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that Slovakia has one of Europe’s best pro-market think tanks, the Institute of Economic and Social Studies. Which hopefully means another wave of reform may happen. Hopefully including some of my favorite policies, such as a pure flat tax as well as some constitutional spending restraint.

P.S. Like other nations in Central and Eastern Europe, Slovakia faces demographic decline. To avert long-term crisis, reform is a necessity, not a luxury.

Indeed, the SAS Party (which I gather must be Slovak initials for Freedom and Solidarity) is so committed to principles that it

Indeed, the SAS Party (which I gather must be Slovak initials for Freedom and Solidarity) is so committed to principles that it