I wrote in 2014, 2017, and 2020 about how free markets and limited government have produced amazing results in Singapore.

Let’s revisit that country and we’ll start with this video from the Fraser Institute.

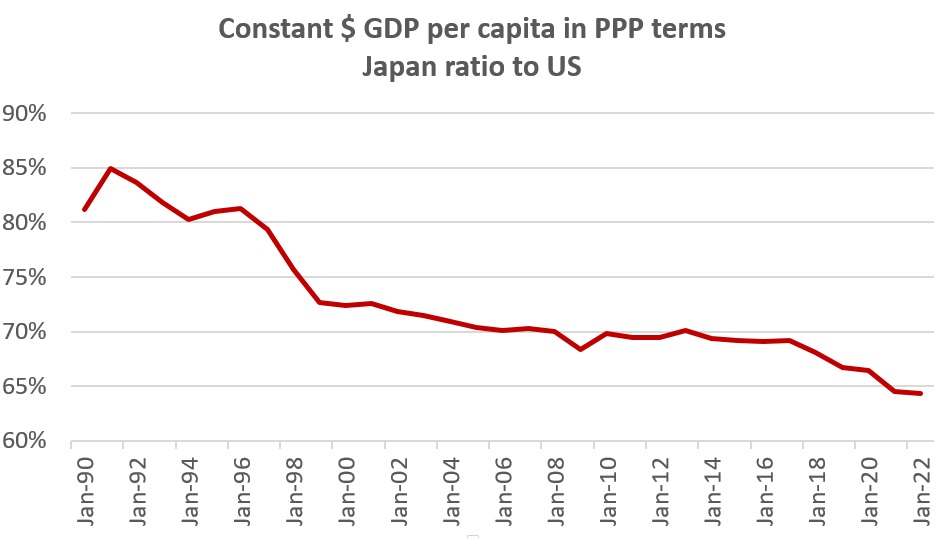

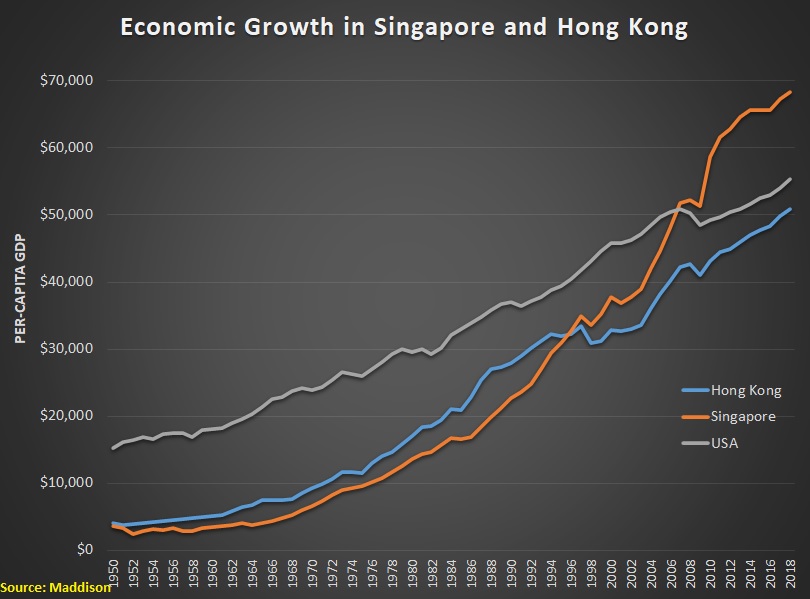

Since the video explains that Singapore emphasized growth, let’s compared the United States and Singapore over the past six decade based on Maddison data.

As you can see, Singapore did a great job of converging with America and now it’s doing an even-better job of diverging.

An article in this week’s Economist lauds Singapore amazing success.

Here are some excerpts.

Singapore has become a beacon of prosperity. In a part of the world where middle-income status is the norm, the city-state is now the richest country for many thousands of miles in any direction. At around $88,000, its GDP per person has doubled in real terms over the past 20 years.

At the moment of its independence in 1965, the country was poorer on the same basis than South Africa or Jordan. …During the past two decades, the median wage for Singaporean residents in full-time work has risen by 43% in real terms, compared with an 8% rise in America. At around $46,000 in dollar terms, the median full-time wages of Singaporeans are now higher than those in Britain, the country’s former colonial boss, where they sit at around $44,000.

Since the article mentions that Singapore used to be poorer than South Africa and Jordan, I can’t resist pointing out that Singapore used to be as poor as Jamaica.

So why is Singapore now one of the world’s richest nations?

For the simple reason that it has free markets and limited government.

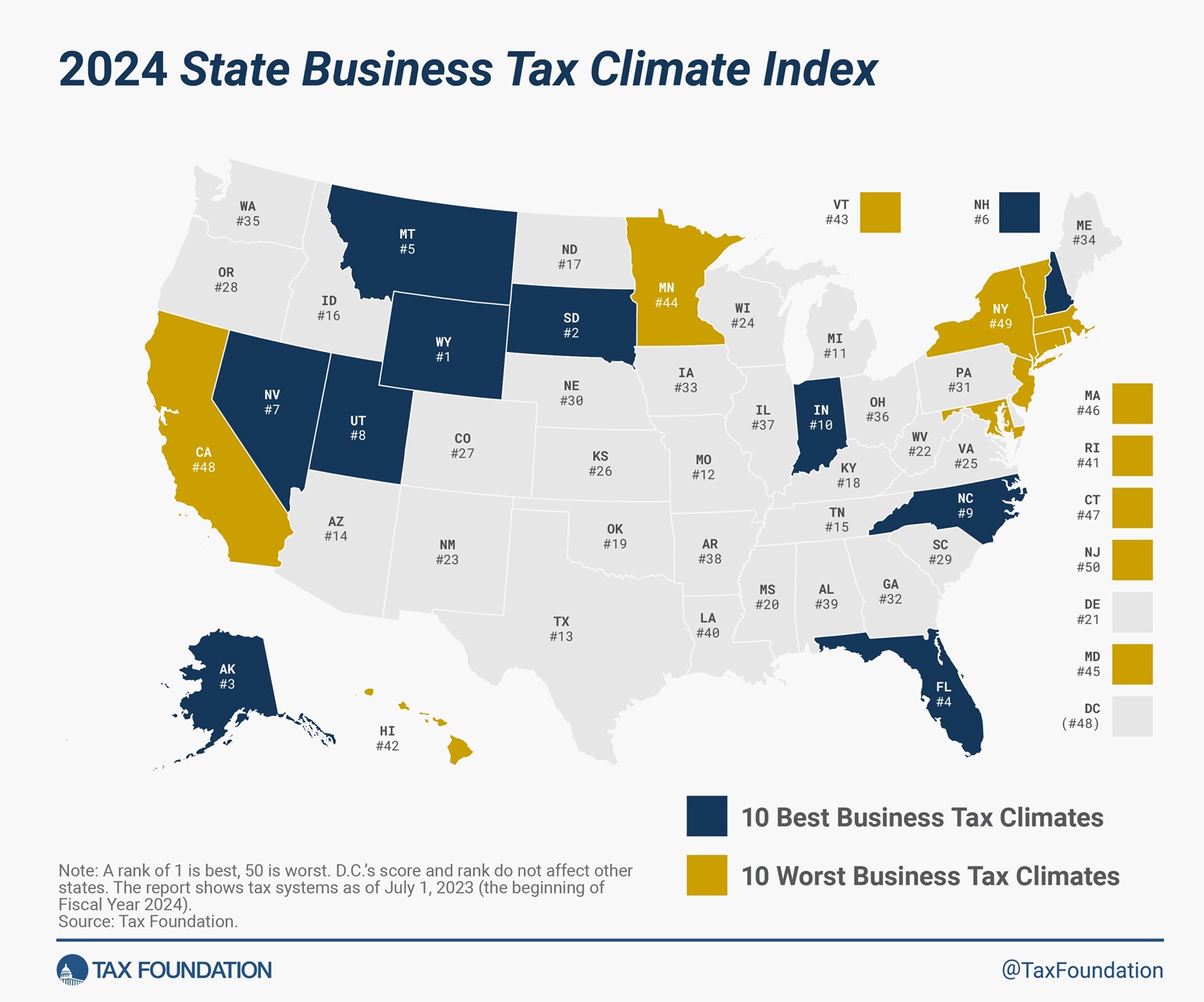

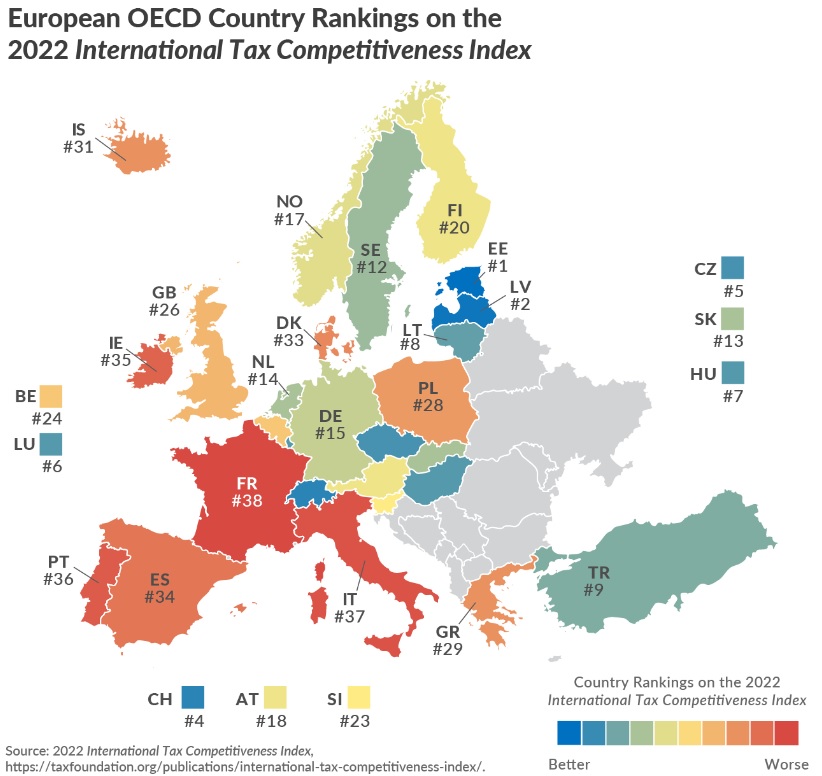

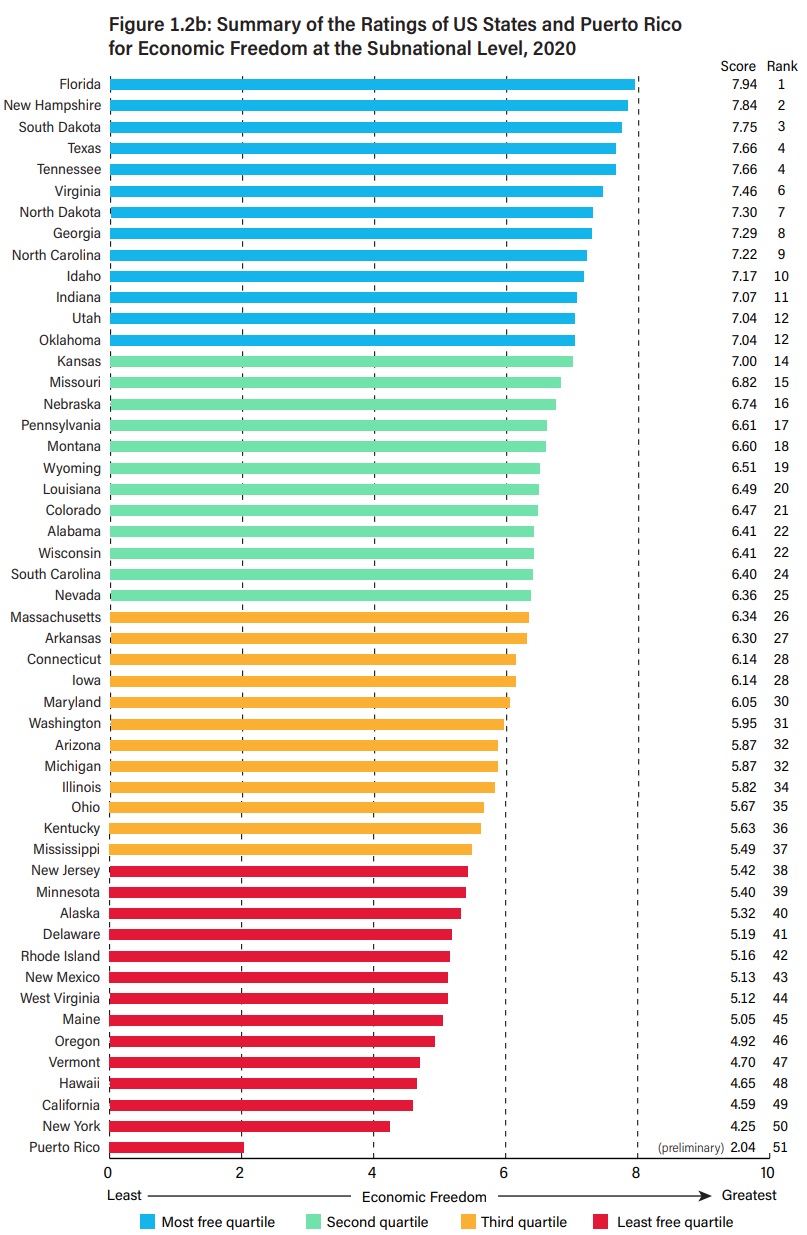

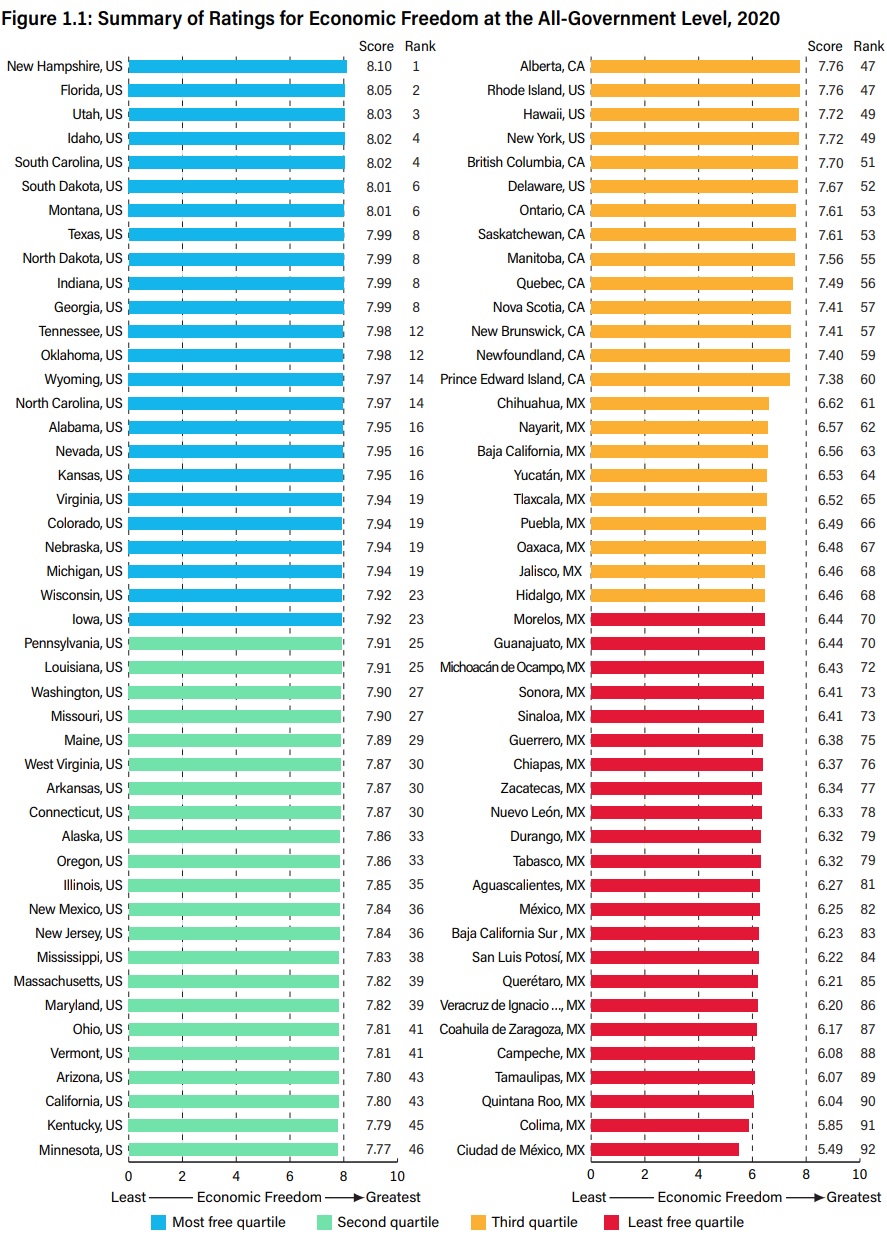

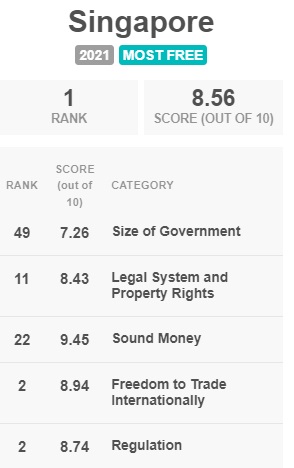

According to Economic Freedom of the World, it has the world’s most market-oriented policies, including total free trade and minuscule levels of red tape.

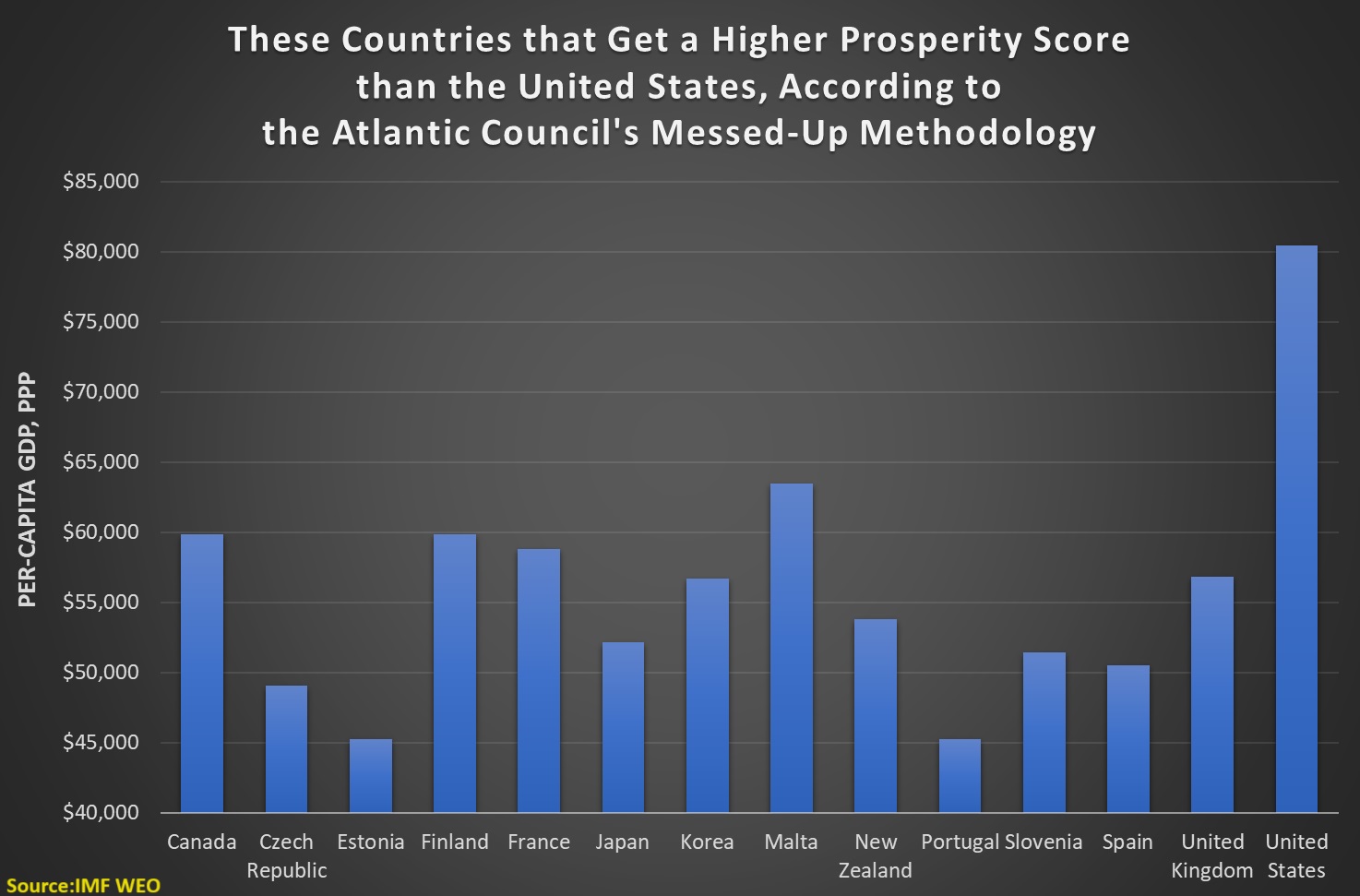

And more economic liberty is strongly correlated with more national prosperity.

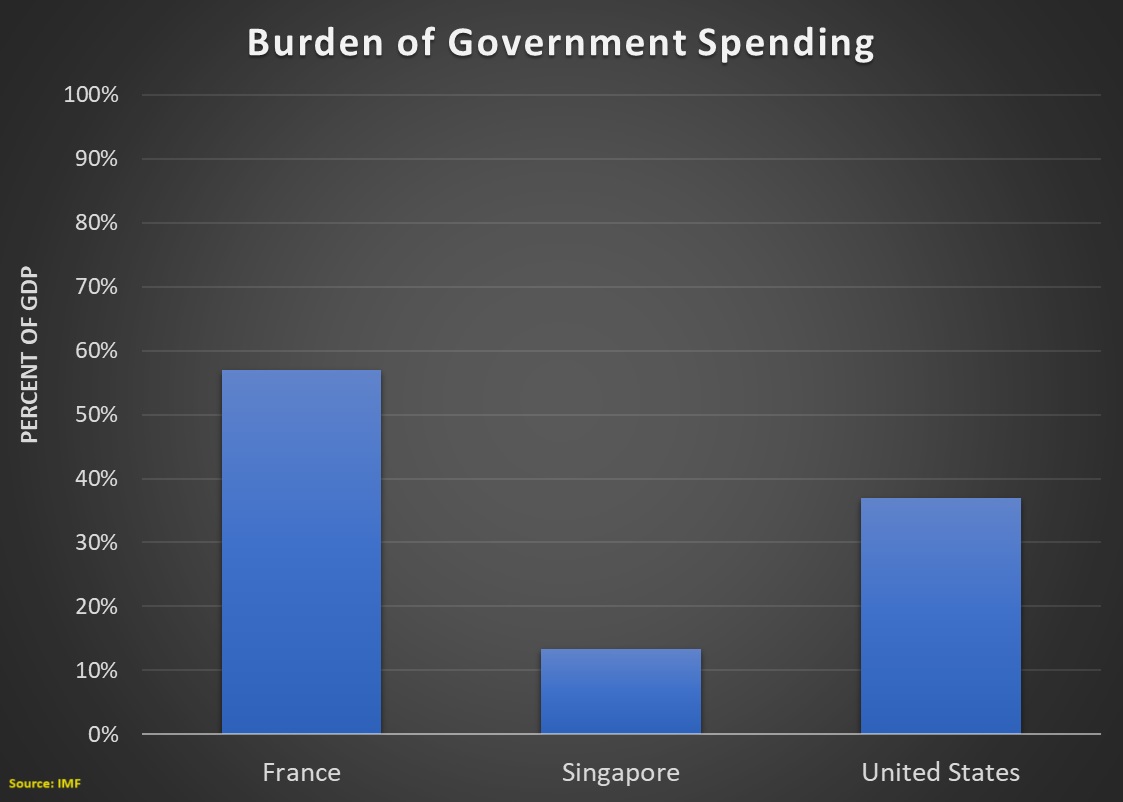

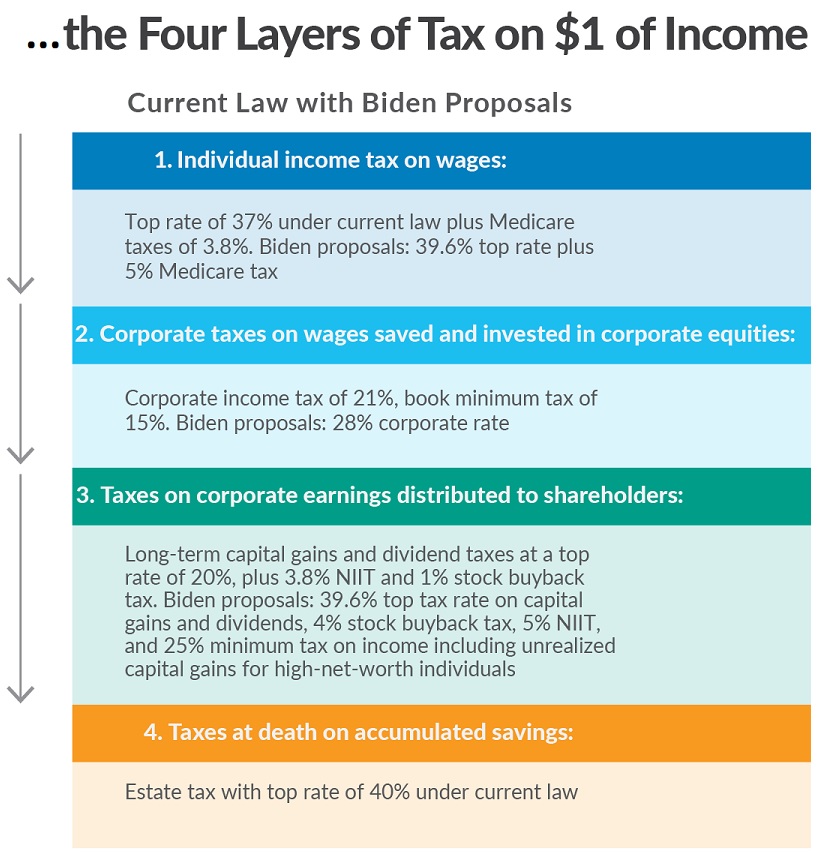

Let’s close with some analysis of Singaporean fiscal policy. Notice that Singapore gets its worst score on size of government, ranking #49.

Yet IMF data shows that the burden of government spending in Singapore is impressively low, with the public sector consuming less than 14 percent of the economy’s output.

So how can Singapore only rank #49 on fiscal policy when it has a very small fiscal burden?

The answer is that the government owns non-trivial chunks of the economy. And even though the video explains that Singapore requires government-owned companies to be efficient, the Fraser Institute correctly lowers the nation’s score for that deviation from laissez-faire policy.

The bottom line is that even a very well-governed nation may have a slice of socialism!

P.S. Hong Kong has now fallen well behind Singapore.

P.P.S. The OECD is infamous for dodgy and biased research, but even I was shocked when the Paris-based bureaucrats pushed for higher taxes in Asia while ignoring the incredible economic success of low-tax Singapore.