The famous French diplomat Charles Maurice de Talleyrand supposedly said that a weakness of  the Bourbon monarchs was that they learned nothing and forgot nothing.

the Bourbon monarchs was that they learned nothing and forgot nothing.

If so, the genetic descendants of the Bourbons are now in charge of Europe.

But before explaining why, let’s first establish that Europe is in trouble. I’ve made that point (many times) that the continent is in trouble because of statism and demographic change.

What’s far more noteworthy, though, is that even the Europeans are waking up to the fact that the continent faces a very grim future.

For instance, the bureaucrats in Brussels are pessimistic, as reported by the EU Observer.

…the report warns of a longer term risk for the EU economy. “As expectations of low growth ahead affect investment today, there is potential for a vicious circle,” the commission’s director general for economic and financial affairs writes in the report’s foreword. “In short, the projected pace of GDP growth may not be sufficient to prevent the cyclical impact of the crisis from becoming permanent (hysteresis), ” Marco Buti writes.

The people of Europe share that grim assessment.

Pew has some very sobering data on angst across the continent.

Support for European economic integration – the 1957 raison d’etre for creating the European Economic Community, the European Union’s predecessor – is down over last year in five of the eight European Union countries surveyed by the Pew Research Center in 2013. Positive views of the European Union are at or near their low point in most EU nations, even among the young, the hope for the EU’s future. The favorability of the EU has fallen from a median of 60% in 2012 to 45% in 2013.

Here’s the relevant chart.

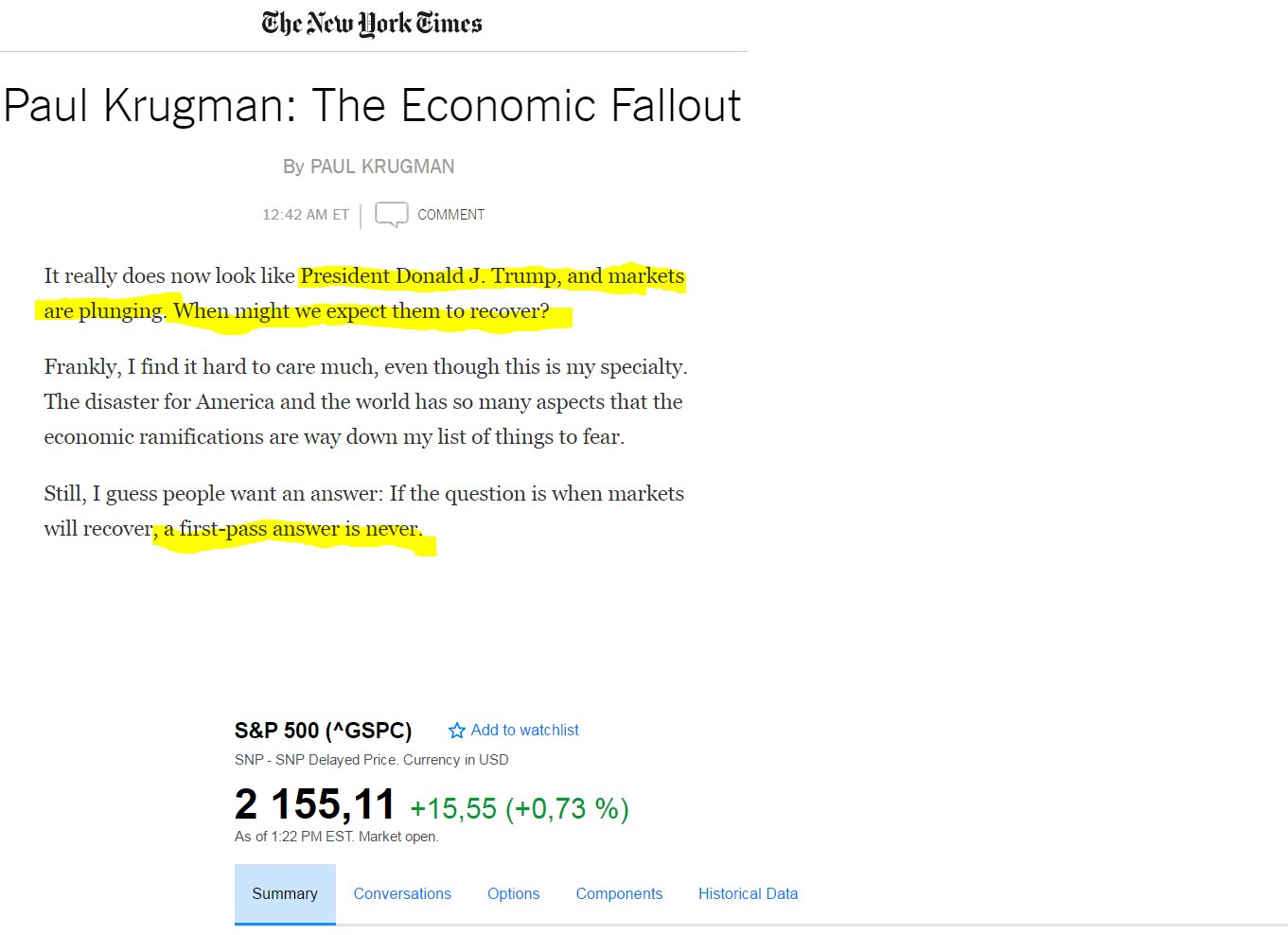

Establishment-oriented voices in the United States also agree that the outlook is rather dismal.

Writing in the Washington Post, Sebastian Mallaby offers a grim assessment of Europe’s future.

…since 2008…, the 28 countries in the European Union managed combined growth of just 4 percent. And in the subset consisting of the eurozone minus Germany, output actually fell. …most of the Mediterranean periphery has suffered a lost decade. …The unemployment rate in the euro area stands at 9.8 percent, more than double the U.S. rate. Unemployment among Europe’s youth is even more appalling: In Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus and Portugal, more than 1 in 4 workers under 25 are jobless.

The bottom line is that there’s widespread consensus that Europe is a mess and that things will probably get worse unless there are big changes.

But the key question, as always, is whether the changes are positive or negative. And this is why I started with a reference to the Bourbon kings. European leaders today also are infamous for learning nothing and forgetting nothing.

Indeed, the proponents of bad policy want to double down on the mistakes of bigger government and more centralization.

The International Monetary Fund (aka, the “Dr. Kevorkian” or “dumpster fire” of the global economy), led by France’s Christine Lagarde, actually is urging a new form of redistribution in Europe.

The International Monetary Fund called on Thursday for the creation of a fund…in the euro zone… Managing Director Christine Lagarde said… “countries would be pooling budgetary resources in a common pot which could be used for projects and certain operations”

Lagarde says the new fund should have strings attached, so that nations could access the loot if they complied with the EU’s budget rules, and also if they use the money for structural reform.

That sounds prudent, but only until you look at the fine print.

The current budget rules are misguided and are more likely to encourage tax hikes rather than spending restraint. And while many European nations need good structural reform, that’s not what the IMF has in mind.

Lagarde told a news conference the new fund could pay for projects related to migration, refugees, security, energy and climate change.

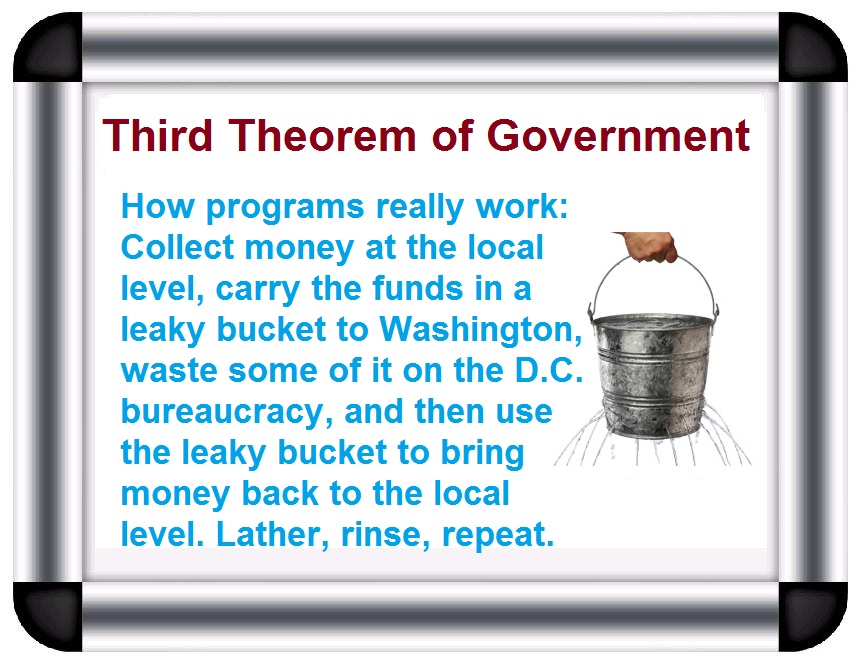

Instead, it appears that this is just a scheme to transfer money from countries such as Germany and Estonia that have restrained spending in recent years.

Germany, Estonia and Luxembourg are the only EU countries that have posted budget surpluses since 2014. Lagarde said the pooling of budgetary resources could put these surpluses to good use.

Sigh.

But the problem goes way beyond an international bureaucracy led by someone from Europe. This is the mentality that is deeply embedded in most European policymakers.

Simply stated, the people who helped create the European mess by pushing for bigger government and more centralization agree that the time if right for…you guessed it…bigger government and more centralization. Here’s an excerpt from a report by the Delors Institute.

…a true economic and monetary union still needs to be built. It will have to be based on significant risk sharing and sovereignty sharing within a coherent and legitimate framework of supranational economic governance. This third building block includes turning the ESM into a fully-fledged European Monetary Fund.

The bureaucrats in Brussels predictably agree that they should get more power, as noted in a story from the EU Observer.

The EU should raise its own taxes and use Brexit as an opportunity to push for the idea, a report by a group of top officials says. …”The Union must mobilise common resources to find common solutions to common problems,” says the document, seen by EUobserver. …The paper also proposes a EU-level corporate income tax that would be combined with a common consolidated corporate tax base… Other proposals include a bank levy, a financial transaction tax, or a European VAT that would top national VATs. …The new budget EU commissioner Guenther Oettinger said that the report was “of great quality”.

And the senior politicians in Brussels are also beating the drum for added centralization.

…divergence creates fragility… Progress must happen…towards a genuine Economic Union…towards a Fiscal Union…need to shift from a system of rules and guidelines for national economic policy-making to a system of further sovereignty sharing within common institutions…some degree of public risk sharing…including a ‘social protection floor’…a shared sense of purpose among all Member States

Wow. I don’t know if I’ve ever read something so wildly wrong. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb has sagely observed, it is centralization and harmonization that creates systemic risk.

And all this talk about “common resources” and “public risk sharing” is simply the governmental version of co-signing a loan for the deadbeat family alcoholic.

And all this talk about “common resources” and “public risk sharing” is simply the governmental version of co-signing a loan for the deadbeat family alcoholic.

Yet Europe’s ideologues can’t resist their lemming-like march in the wrong direction.

What makes this especially odd is that there is so much evidence that Europe originally became rich for the opposite reason.

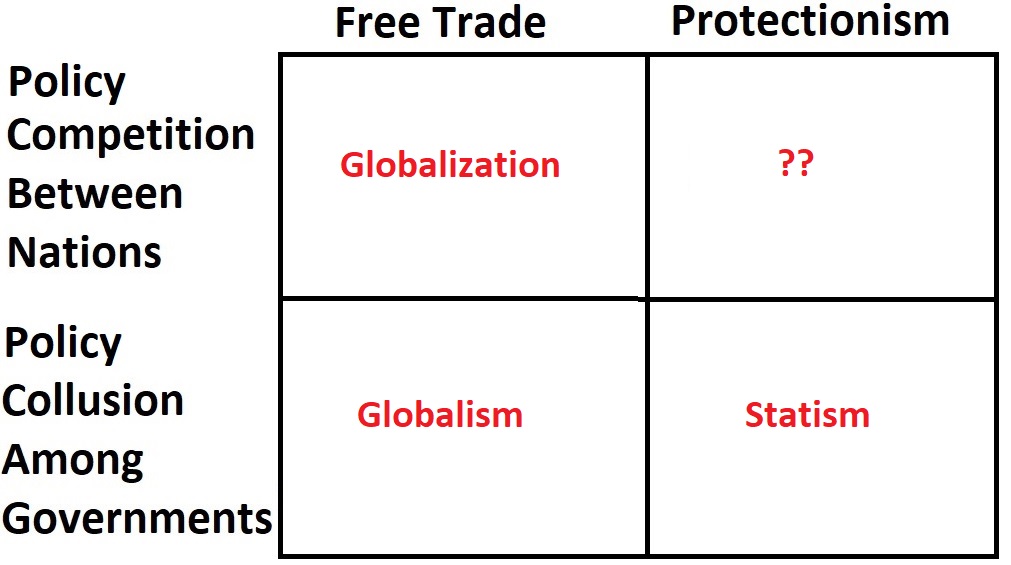

It was decentralization and jurisdictional competition that enabled prosperity.

Matt Ridley, writing for the UK-based Times, drives this point home.

…the leading theory among economic historians for why Europe after 1400 became the wealthiest and most innovative continent is political fragmentation. Precisely because it was not unified, Europe became a laboratory for different ways of governing, enabling the discovery of regimes that allowed free markets and invention to flourish, first in northern Italy and some parts of Germany, then the low countries, then Britain. By contrast, China’s unity under one ruler prevented such experimentation. …Baron Montesquieu…remarked, Europe’s “many medium-sized states” had incubated “a genius for liberty, which makes it very difficult to subjugate each part and to put it under a foreign force other than by laws and by what is useful to its commerce”. …David Hume…mused…Europe is the continent “most broken by seas, rivers, and mountains” and so “the divisions into small states are favourable to learning, by stopping the progress of authority as well as that of power”. …the idea has gained almost universal agreement among historians that a disunited Europe, while frequently wracked by war, was also prone to innovation and liberty — thanks to the ability of innovators and skilled craftsmen to cross borders in search of more congenial regimes.

But now Europe has swung completely in the other direction.

The European Commission’s obsession with harmonisation prevents the very pattern of experimentation that encourages innovation. Whereas the states system positively encouraged governments to be moderate in political, religious and fiscal terms or lose their talent, the commission detests jurisdictional competition, in taxes and regulations. The larger the empire, the less brake there is on governmental excess.

Ralph Raico echoes these insights in an article for the Foundation for Economic Education.

In seeking to answer the question why the industrial breakthrough occurred first in western Europe, …what was it that permitted private enterprise to flourish? …Europe’s radical decentralization… In contrast to other cultures — especially China, India, and the Islamic world — Europe comprised a system of divided and, hence, competing powers and jurisdictions. …Instead of experiencing the hegemony of a universal empire, Europe developed into a mosaic of kingdoms, principalities, city-states, ecclesiastical domains, and other political entities. Within this system, it was highly imprudent for any prince to attempt to infringe property rights in the manner customary elsewhere in the world. In constant rivalry with one another, princes found that outright expropriations, confiscatory taxation, and the blocking of trade did not go unpunished. The punishment was to be compelled to witness the relative economic progress of one’s rivals, often through the movement of capital, and capitalists, to neighboring realms. The possibility of “exit,” facilitated by geographical compactness and, especially, by cultural affinity, acted to transform the state into a “constrained predator”.

In other words, the “stationary bandit” couldn’t steal as much and that gave the private sector the breathing room that’s necessary for growth.

But today’s politicians in Europe want to strengthen the ability of governments to seize more money and power.

That strategy may work in the short run, but bailouts, redistribution, easy money, and statism are not a good long-run strategy.

So perhaps it’s appropriate that we conclude with a warning. As reported in a column for the UK-based Telegraph, one of the architects of the euro fears that bailouts are crippling the continent-wide currency.

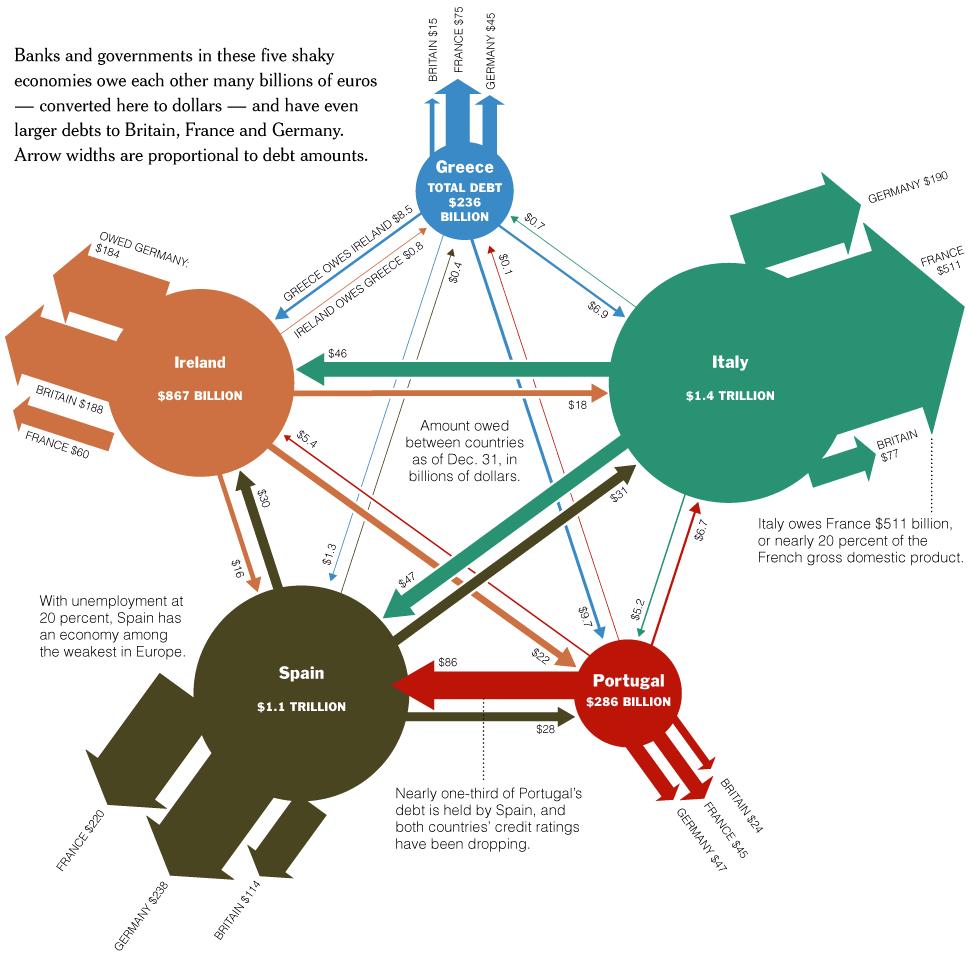

The European Central Bank is becoming dangerously over-extended and the whole euro project is unworkable in its current form, the founding architect of the monetary union has warned. “One day, the house of cards will collapse,” said Professor Otmar Issing, the ECB’s first chief economist… Prof Issing lambasted the European Commission as a creature of political forces that has given up trying to enforce the rules in any meaningful way. “The moral hazard is overwhelming,” he said. The European Central Bank is on a “slippery slope” and has in his view fatally compromised the system by bailing out bankrupt states in palpable violation of the treaties. “…Market discipline is done away with by ECB interventions. …The no bailout clause is violated every day,” he said… Prof Issing slammed the first Greek rescue in 2010 as little more than a bailout for German and French banks, insisting that it would have been far better to eject Greece from the euro as a salutary lesson for all.

For what it’s worth, I fully agree that Greece should have been cut loose.

But European politicians and bureaucrats, driven by an ideological belief in centralization (and a desire to bail out their big banks), instead decided to undermine the euro by creating a bigger mess in Greece and sending a very bad signal about bailouts to other welfare states.

And keep in mind that the fuse is still burning on the European fiscal crisis.

As the old saying goes, this won’t end well.

P.S. While my prognosis for Europe is relatively bleak, there were some hopeful signs in the aforementioned Pew data.

First, Europeans at some level understand that government is simply too big. Indeed, they recognize that economic growth is far more likely to occur if fiscal burdens are reduced rather than increased.

Second, they also realize that the euro, while weakened and flawed, is a better option than restoring national currencies, which would give their governments the power to finance bigger government by printing money.

P.P.S. I can’t resist sharing one final bit of polling data from Pew. I’m amused that every nation sees itself as the most compassionate (though if you look at real data, all European nations lag the USA in real compassion). Meanwhile, the prize for self-doubt (or perhaps self-awareness?) goes to the Italians, who labeled themselves as least trustworthy. The schizophrenia prize goes to the Poles, who simultaneously view the Germans as the most trustworthy and least trustworthy.

Oh, and there’s probably some lesson to be learned from Germany dominating the data for being most trustworthy and least compassionate.

Maybe this poll should be added to my European humor collection.

P.P.P.S. Given the sorry state of Europe, now perhaps skeptics will understand why Brexit was the only good option for Brits.

Read Full Post »

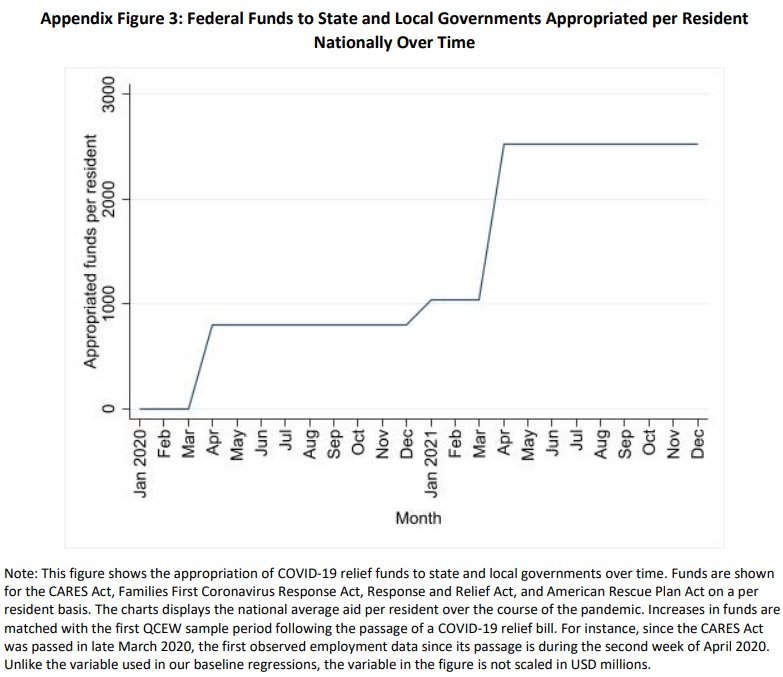

But that’s unwise. What happens in Europe can have an impact on policy in the United States.

But that’s unwise. What happens in Europe can have an impact on policy in the United States.…A big polity can prosper, but only if it behaves like a confederation of statelets. The supreme exemplar is the U.S., the only large nation that gets anywhere near the top of those GDP rankings… I’m not wild about the direction the U.S. has been taking… But the U.S. is starting from a much better place. It was designed according to Jeffersonian principles. Power was dispersed, decentralized, and democratized. The E.U., by contrast, was designed to weld nations into a supranational bloc. …Where the Declaration of Independence promises life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, its European equivalent, the Charter of Fundamental Rights, entitles people to “strike action,” “affordable housing,” and “free healthcare.”

Those alternatives almost certainly involve protectionism, heavy-handed industrial policy and planning, or state aid to politically connected companies… If it weren’t for the pressure of the European Commission in the late 1980s, it is fanciful to think that Italy or France would have just given up state ownership of utilities, banks, or their industrial giants. …Conversely, the United Kingdom has not become a free market paradise after leaving the European Union. Quite the opposite. …the E.U.’s “single market” is far from perfect. …it often goes hand in hand with harmonized European rules rather than with simple mutual recognition of national standards. …Has the E.U. lived up fully to the ideals of Hayekian international federalism? Of course not. But it is blindingly obvious that it has performed better than the relevant alternatives.

…let’s look at some data. There is no hard definition of “infrastructure,” but one broad measure is gross fixed investment in the BEA national accounts. …The first thing to note is that private investment at about $3 trillion was six times larger than combined federal, state, and local government nondefense investment of $472 billion. Private investment in pipelines, broadband, refineries, factories, cell towers, and other items greatly exceeds government investment in schools, highways, prisons, and the like. …if policymakers want to boost infrastructure spending, they should reduce barriers to private investment.

…let’s look at some data. There is no hard definition of “infrastructure,” but one broad measure is gross fixed investment in the BEA national accounts. …The first thing to note is that private investment at about $3 trillion was six times larger than combined federal, state, and local government nondefense investment of $472 billion. Private investment in pipelines, broadband, refineries, factories, cell towers, and other items greatly exceeds government investment in schools, highways, prisons, and the like. …if policymakers want to boost infrastructure spending, they should reduce barriers to private investment.

…The Hanseatic cities had their own legal system and furnished their own armies for mutual protection and aid. Despite this, the organization was not a state… Much of the drive for this co-operation came from the fragmented nature of existing territorial government, which failed to provide security for trade. Over the next 50 years the Hansa itself emerged with formal agreements for confederation and co-operation covering the west and east trade routes. The principal city and linchpin remained Lübeck; with the first general Diet of the Hansa held there in 1356, the Hanseatic League acquired an official structure.

…The Hanseatic cities had their own legal system and furnished their own armies for mutual protection and aid. Despite this, the organization was not a state… Much of the drive for this co-operation came from the fragmented nature of existing territorial government, which failed to provide security for trade. Over the next 50 years the Hansa itself emerged with formal agreements for confederation and co-operation covering the west and east trade routes. The principal city and linchpin remained Lübeck; with the first general Diet of the Hansa held there in 1356, the Hanseatic League acquired an official structure.

He called for a vanguard of countries that would lead the eurozone, which should have its own government, a “specific budget” and its own parliament. …French prime minister Manuel Valls Sunday said…France would prepare “concrete proposals” in the coming weeks. “We must learn the lessons and go much further,” he added, referring to the Greek crisis.

He called for a vanguard of countries that would lead the eurozone, which should have its own government, a “specific budget” and its own parliament. …French prime minister Manuel Valls Sunday said…France would prepare “concrete proposals” in the coming weeks. “We must learn the lessons and go much further,” he added, referring to the Greek crisis.