Two years ago, I shared a study from three scholars that investigated whether membership in the European Union (EU) is associated with better economic performance.

Before reading that study, I assumed that EU membership was bad news for rich countries with decent economic policy (hence my support for Brexit), but I figured it was a good idea for poor countries with not-so-good policy.

Before reading that study, I assumed that EU membership was bad news for rich countries with decent economic policy (hence my support for Brexit), but I figured it was a good idea for poor countries with not-so-good policy.

I may have been wrong about the latter. The authors found that “EU membership has no impact on economic growth” and that “EU entry seems to have reduced economic growth.”

Ouch.

But I’m always interested in seeing new research on this topic.

So I was delighted to read a new report published by the European Liberal Forum.* Written by Constantinos Saravakos, Emmanuel Schizas, Mara Vidali, Angela De Martiis, and Giorgio Vernoni, it also seeks to ascertain if there is a link between EU membership and economic liberty.

…this publication seeks to examine whether a trajectory towards EU membership is a driver for more economic freedom. The key research question is if European Union economic policies promote economic freedom. The answer in this question is essential…because an economic environment based on market economy has a positive relationship with several prosperity outcomes.

…Taking into account the huge EU enlargement that took place since 2004, when 13 countries have accessed the Union, and the on process enlargement with several formal or informal candidates, the analysis focuses on whether the structural reforms required for a country to become a member of EU contribute to economic freedom, covering the period from 2000 to 2017. …our research considers the relationship between a country’s Economic Freedom of the World index score (and sub-index scores) and its progress along the EU accession process.

Contrary to the study I wrote about two years ago, they find that countries have benefited from membership.

…as a country approaches EU membership status, then economic freedom, as proxied by the proximity to the EFW frontier, increases by at least 0.2, and this effect is associated with the process of accession…the main channel by which EU accession might contribute positively to a candidate or member state’s economic freedom is by boosting the freedom to trade… The present study provides empirical evidence of a link between the EU accession process and the aim of promoting economic freedom.

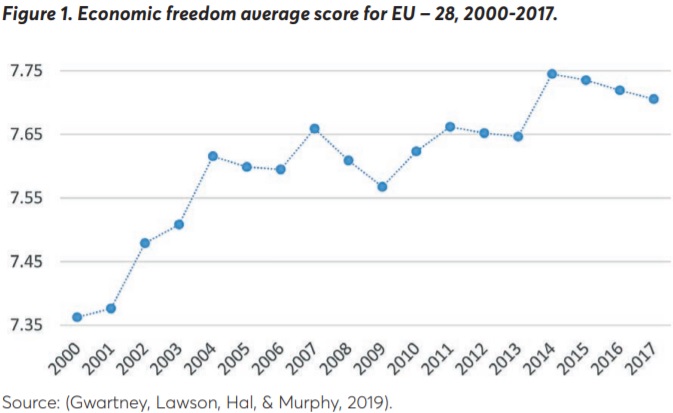

Here’s a chart from the report, which certainly suggests that something good is happening in the European Union.

Economic freedom, on average, has increased for the 28 nations of the EU since 2000 (based on a 1-10 scale).**

But when I looked at that chart, I wondered what we were really seeing.

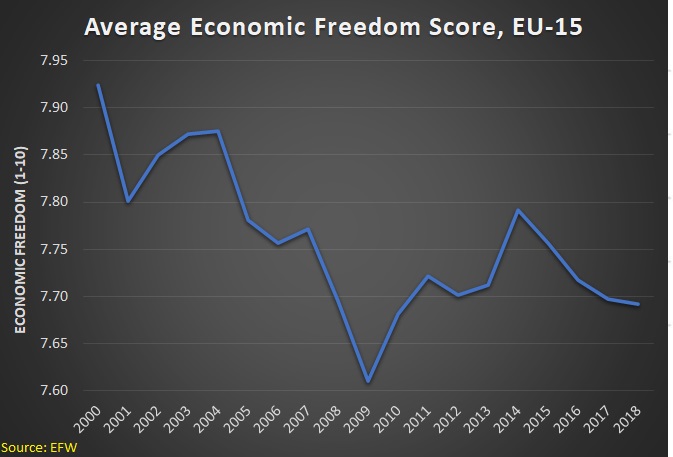

Most notably, I was curious what we would find if we looked at the the nations of Western Europe, the ones that used to be known as the EU-15 before the bloc was enlarged (13 new countries have joined this century, mostly from Eastern Europe).**

So I went to the same source, Economic Freedom of the World, to measure what’s happened in those countries. Lo and behold, the average level of economic liberty has declined (which didn’t surprise me since I found something similar when I crunched some data back in 2016).

This doesn’t mean we should necessarily conclude that EU membership is bad for prosperity, but I’m not optimistic.

When I talk to pro-EU friends, here are some questions I ask:

- Would Eastern European nations have liberalized their economies without becoming part of the EU?

- Since Western European nations wield most of the power inside the EU, is it worrisome that they are becoming more statist in their orientation?

- What are the implications for EU nations of demographic change (aging populations and falling birthrates)?

- Will the EU’s nascent transfer union lead to more economic liberalization or less economic liberalization?

The bottom line is that I don’t think there are encouraging answers to these questions. Which is why we can expect that Europe will continue to fall behind the United States (which makes it rather odd that President Biden wants to make the USA more like the EU).

*In Europe, liberal means pro-market “classical liberalism” rather than the entitlement-based American version.

**The United Kingdom has now escaped the EU, but it was part of the bloc during the periods being measured.

[…] years ago, I wrote about the erosion of economic liberty in Western Europe (specifically, the 15 nations that comprised the […]

[…] already mentioned falling scores for the United States this century. And the same unfortunate trend is confirmed by data for Western Europe from Economic Freedom of the […]

[…] the other hand, I have tepidly written that E.U. membership may make sense for nations from Eastern […]

[…] Unfortunately, the opposite has happened in the 21st century. The United States has moved toward statism and the same is true for Japan and most of Western Europe. […]

[…] because they get subsidies, of course, but because EU membership means better rule of […]

[…] main argument for Brexit was to escape the European Union, which is destined to become a “transfer […]

[…] Needless to say, the EU model of governance (centralization, harmonization, and bureaucratization) is not a good idea. […]

[…] because the level of economic liberty has declined in the United States since 2000. It’s also declined in Western Europe. And it’s declined slightly in […]

[…] Policy has drifted in the wrong direction, by contrast, in the United States and Western Europe. […]

[…] (and I have knee-jerk fondness for Hungary because it’s often butting heads with the dirigiste bureaucrats with the European Union in […]

[…] Over the next four years (and beyond), it’s quite likely that the biggest threat to global trade will be the European Union. […]

[…] Over the next four years (and beyond), it’s quite likely that the biggest threat to global trade will be the European Union. […]

[…] reason to think that OECD membership will lead to better policy and there are good reasons to think EU membership might push policy in the wrong […]

Should index the EU score to the world score. Indeed, when they publish annually, it would be interesting to see how the distribution changes over time. 0-10 x-axis, year y-axis, score z-axis.

I often ask Remain voters if they are able to name the EU’s biggest budget item, describe what class of people gets the handouts, and cite their best paper to show that the centralised to Brussels policy gives better outcomes than the two most obvious alternatives.

So far, no-one I have asked has got past part one of this question (the answer is farmland owner subsidies btw).