Ronald Reagan must be turning over in his grave.

This newfound flirtation with industrial policy, mostly from nationalist conservatives, is especially noxious since you open the door to cronyism and corruption when you give politicians and bureaucrats the power to play favorites in the economy.

I’m going to cite three leading proponents of industrial policy. To be fair, none of them are proposing  full-scale Soviet-style central planning.

full-scale Soviet-style central planning.

But it is fair to say that they envision something akin to Japan’s policies in the 1980s.

Some of them even explicitly argue we should copy China’s current policies.

In a column for the New York Times, Julius Krein celebrates the fact that Marco Rubio and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez both believe politicians should have more power over the economy.

…a few years ago, the phrase “industrial policy” was employed mainly as a term of abuse. Economists almost universally insisted that state interventions to improve competitiveness, prioritize investment in strategic sectors and structure market incentives around political goals were backward policies doomed to failure — whether applied in America, Asia or anywhere in between. …In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, however, the Reagan-Bush-Clinton neoliberal consensus seems intellectually and politically bankrupt. …a growing number of politicians and intellectuals…are finding common ground under the banner of industrial policy. Even the typically neoliberal Financial Times editorial board recently argued in favor of industrial policy, calling on the United States to “drop concerns around state planning.” …Why now? The United States has essentially experienced two lost decades, and inequality has reached Gilded Age levels. …United States industry is losing ground to foreign competitors on price, quality and technology. In many areas, our manufacturing capacity cannot compete with what exists in Asia.

…In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, however, the Reagan-Bush-Clinton neoliberal consensus seems intellectually and politically bankrupt. …a growing number of politicians and intellectuals…are finding common ground under the banner of industrial policy. Even the typically neoliberal Financial Times editorial board recently argued in favor of industrial policy, calling on the United States to “drop concerns around state planning.” …Why now? The United States has essentially experienced two lost decades, and inequality has reached Gilded Age levels. …United States industry is losing ground to foreign competitors on price, quality and technology. In many areas, our manufacturing capacity cannot compete with what exists in Asia.

There are some very sloppy assertions in the above passages.

You can certainly argue that Reagan and Clinton had similar “neoliberal” policies (i.e., classical liberal), but Bush was a statist.

Also, the Financial Times very much leans to the left. Not crazy Sanders-Corbyn leftism, but consistently in favor of a larger role for government.

Anyhow, what exactly does Mr. Krein have in mind?

More spending, more intervention, and more cronyism.

A successful American industrial policy would draw on replicable foreign models as well as take lessons from our history. Some simple first steps would be to update the Small Business Investment Company and Small Business Innovation Research programs — which played a role in catalyzing Silicon Valley decades ago — to focus more on domestic hardware businesses. …Government agencies could also step in to seed investment funds focused on strategic industries and to incentivize commercial lending to key sectors, policies that have proven successful in other countries… the United States needs to invest more in applied research… Elizabeth Warren has also proposed a government-sponsored research and licensing model for the pharmaceutical industry, which could be applied to other industries as well. …Senator Gary Peters, Democrat of Michigan, has called for the creation of a National Institute of Manufacturing, taking inspiration from the National Institutes of Health. …A successful industrial policy would aim to strengthen worker bargaining power while organizing and training a better skilled labor force. Industrial policy also involves, and even depends upon, rebuilding infrastructure.

In other words, if you like the so-called Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal and Elizabeth Warren’s corporate cronyism, you’ll love all the other ideas for additional government intervention.

Oren Cass of the Manhattan Institute also wants to give politicians more control over the private economy.

My argument rests on three claims… First, that market economies do not automatically allocate resources well across sectors. Second, that policymakers have tools that can support vital sectors that might otherwise suffer from underinvestment—I will call those tools “industrial policy.” Third, that while the policies produced by our political system will be far from ideal, efforts at sensible industrial policy can improve upon our status quo, which is itself far from ideal. …Our popular obsession with manufacturing isn’t some nostalgic anachronism. …manufacturing is unique for the complexity of its supply chains and the interaction between innovation and production. …the case for industrial policy requires recognition not only of certain sectors’ value, but also that the market will overlook the value in theory and that we are underinvesting in practice. That the free market will not solve this should be fairly self-evident… Manufacturing output is only 12% of GDP in America… Productivity growth has slowed nationwide, even flatlining in recent years. Wages have stagnated. Our trade deficit has skyrocketed.

efforts at sensible industrial policy can improve upon our status quo, which is itself far from ideal. …Our popular obsession with manufacturing isn’t some nostalgic anachronism. …manufacturing is unique for the complexity of its supply chains and the interaction between innovation and production. …the case for industrial policy requires recognition not only of certain sectors’ value, but also that the market will overlook the value in theory and that we are underinvesting in practice. That the free market will not solve this should be fairly self-evident… Manufacturing output is only 12% of GDP in America… Productivity growth has slowed nationwide, even flatlining in recent years. Wages have stagnated. Our trade deficit has skyrocketed.

So what are his solutions?

Like Julius Krein, he wants government intervention. Lots of it.

Fund basic research across the sciences… Fund applied research… Support private-sector R&D and commercialization with subsidies and specialized institutes… Increase infrastructure investment… Bias the tax code in favor of profits generated from the productive use of labor… Retaliate aggressively against mercantilist countries that undermine market competition… Tax foreign acquisition of U.S. assets, making U.S. goods relatively more attractive… Impose local content requirements in key supply chains like communications… Libertarians often posit an ideal world of policy non-intervention as superior to the messy reality of policy action. But that ideal does not exist—messy reality is the only reality… That’s especially the case here, because you can have free trade, or you can have free markets, but you can’t have both.

I’m not sure what’s worse, an infrastructure boondoggle or a tax on inbound investment?

More tinkering with the tax code, or more handouts for industries?

And here are excerpts from a column for the Daily Caller by Robert Atkinson.

When the idea first surfaced in the late 1970s that the United States should adopt a national industrial policy, mainstream “free market” conservatives decried it as one step away from handing the reins of the economy over to a state planning committee like the Soviet Gosplan. But now, …the idea has been getting a fresh look among some conservatives who argue that, absent an industrial strategy, America will be at a competitive disadvantage. …Conservatives’ skepticism of industrial policy perhaps stems from the idea’s origins. It started gaining currency during the Carter administration, with many traditional Democratic party interests, including labor unions and politicians in the Northeast and Midwest, arguing for a strong federal role… However, over the next decade, as economic competitors like Germany and Japan began to challenge the United States in consumer electronics, autos, and even high-tech industries like computer chips, the focus of debates about industrial policy broadened to encompass overall U.S. competitiveness. …There was a bipartisan response…that collectively amounted to a first draft of a national industrial policy… But as the economic challenge from Japan receded…, interest in industrial policies waned. …The newly dominant neoclassical economists preached that the U.S. “recipe” of free markets, property rights, and entrepreneurial spirit inoculated America against any and all economic threats.

…Conservatives’ skepticism of industrial policy perhaps stems from the idea’s origins. It started gaining currency during the Carter administration, with many traditional Democratic party interests, including labor unions and politicians in the Northeast and Midwest, arguing for a strong federal role… However, over the next decade, as economic competitors like Germany and Japan began to challenge the United States in consumer electronics, autos, and even high-tech industries like computer chips, the focus of debates about industrial policy broadened to encompass overall U.S. competitiveness. …There was a bipartisan response…that collectively amounted to a first draft of a national industrial policy… But as the economic challenge from Japan receded…, interest in industrial policies waned. …The newly dominant neoclassical economists preached that the U.S. “recipe” of free markets, property rights, and entrepreneurial spirit inoculated America against any and all economic threats.

As with Krein and Cass, Atkinson wants to copy the failed interventionist policies of other nations.

But that was then and this is now — a now where we face intense competition from China. …Increasingly leaders across the political spectrum are returning to a notion that we should put the national interest at the center of economic policies, and that free-market globalization doesn’t necessarily do that… Conservatives increasingly realize that without some kind of industrial policy the United States will fall behind China, with significant national security and economic implications. …So, what would a conservative-inspired, market-strengthening industrial policy look like? …it would acknowledge that America’s “traded sector” industries are critical to our future competitiveness… The right industrial policy will advance prosperity more than laisse-faire capitalism would. …there are a significant number of market failures around innovation, including externalities, network failures, system interdependencies, and the public-goods nature of technology platforms. …this is why only government can “pick winners.” …It should mean expanding supports for exporters by ensuring the Ex-Im Bank has adequate lending authority… this debate boils down to a fundamental choice for conservatives: small government and liberty versus stronger…government that delivers economic security

What’s a “market-strengthening industrial policy”? Is that like a “growth-stimulating tax increase”? Or a “work-ethic-enhancing welfare program”?

I realize I’m being snarky, but how else should I respond to someone who actually wants to expand the cronyist Export-Import Bank?

Let’s now look at what’s wrong with industrial policy.

In a column for Reason, Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center warns that American politicians who favor industrial policy are misreading China’s economic history.

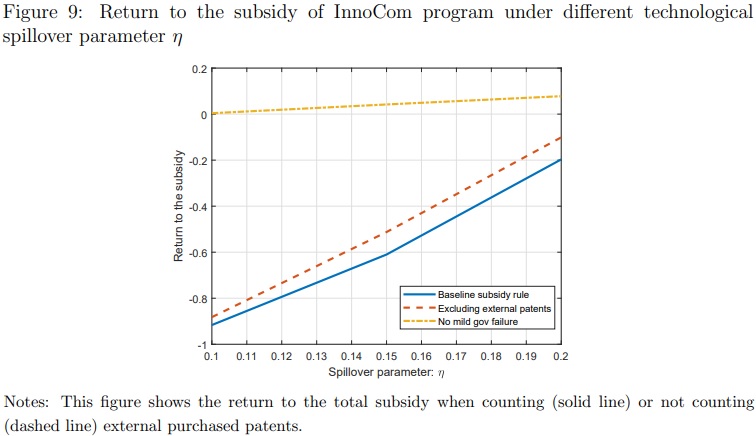

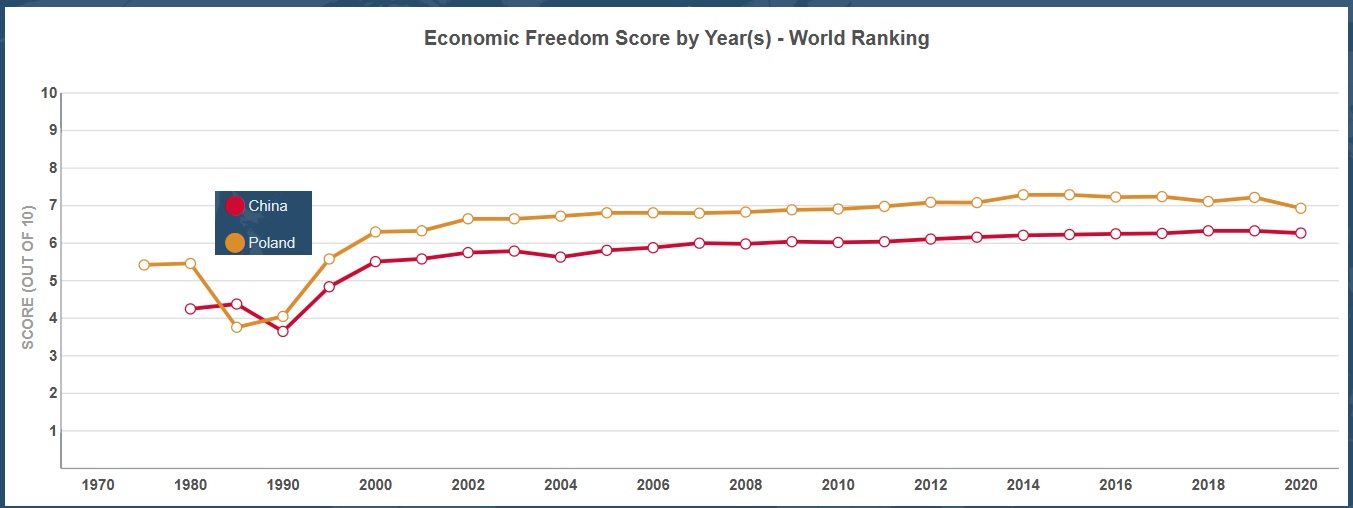

…calls from politicians on both sides of the aisle to implement industrial policy. …These policies are tired, utterly uninspiring schemes that governments around the world have tried and, invariably, failed at. …As for the notion that “other countries are doing it,” I’m curious to hear what great successes have come out of, say, China’s industrial policies. In his latest book, The State Strikes Back: The End of Economic Reform in China?, Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that China’s growth since 1978 has actually been the product of market-oriented reforms, not state-owned programs. …Why should we want America to become more like China? Here’s yet another politician thinking that somehow, the same government that…botched the launch of HealthCare.gov, gave us the Solyndra scandal, and can keep neither Amtrak nor the Postal Service solvent, can effectively coordinate a strategic vision for American manufacturing. …The real problem with industrial policy, economic development strategy, central planning, or whatever you want to call these interventions is that government officials…cannot outperform the wisdom of the market at picking winners. In fact, government intervention in any sector creates distortions, misdirects investments toward politically favored companies, and hinders the ability of unsubsidized competitors to offer better alternatives. Central planning in all forms is poisonous to innovation.

of the Peterson Institute for International Economics shows that China’s growth since 1978 has actually been the product of market-oriented reforms, not state-owned programs. …Why should we want America to become more like China? Here’s yet another politician thinking that somehow, the same government that…botched the launch of HealthCare.gov, gave us the Solyndra scandal, and can keep neither Amtrak nor the Postal Service solvent, can effectively coordinate a strategic vision for American manufacturing. …The real problem with industrial policy, economic development strategy, central planning, or whatever you want to call these interventions is that government officials…cannot outperform the wisdom of the market at picking winners. In fact, government intervention in any sector creates distortions, misdirects investments toward politically favored companies, and hinders the ability of unsubsidized competitors to offer better alternatives. Central planning in all forms is poisonous to innovation.

As usual, Veronique is spot one.

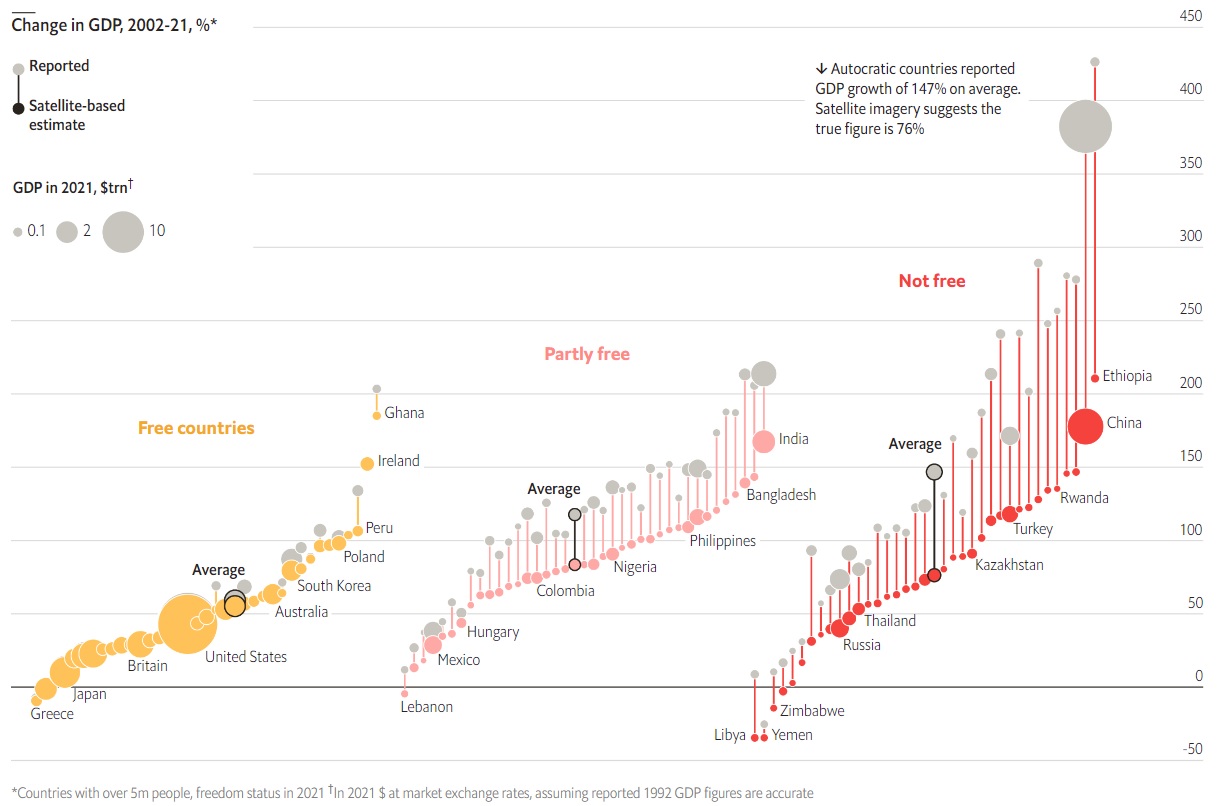

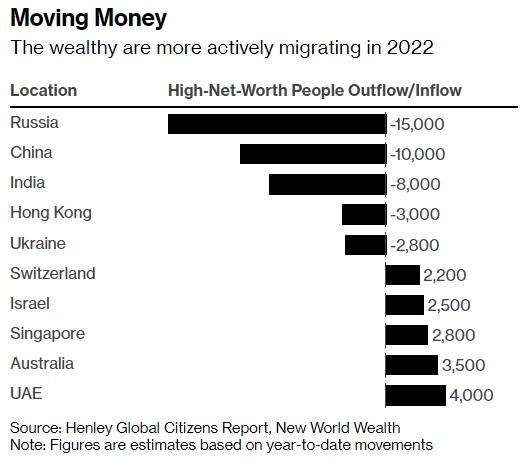

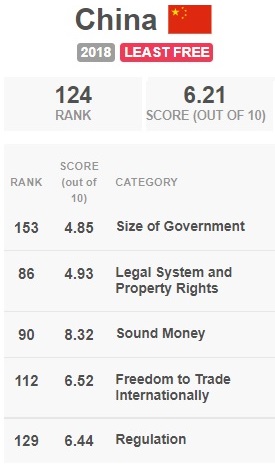

I’ve also explained that China’s economy is being held back by statist policies.

Veronique also addressed the topic of industrial policy in a column for the New York Times,

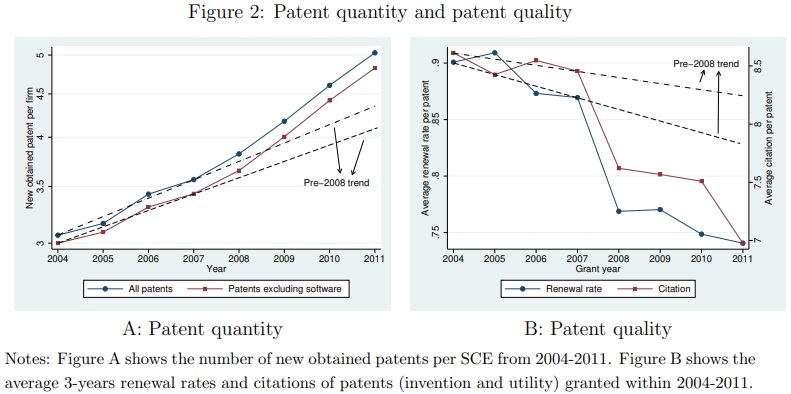

With “Made in China 2025,” Beijing’s 2015 anticapitalist plan for an industrial policy under which the state would pick “winners,” China has taken a step back from capitalism. …China’s new industrial policy has worked one marvel — namely, scaring many American conservatives into believing that the main driver of economic growth isn’t the market but bureaucrats invested with power to control the allocation of natural and financial resources.  …I thought we learned this lesson after many American intellectuals, economists and politicians were proven spectacularly wrong in predicting that the Soviet Union would become an economic rival. …government officials cannot outperform the market at picking winners. In practice it ends up picking losers or hindering the abilities of the winners to achieve their greatest potential. Central planning is antithetical to innovation, as is already visible in China. …the United States has instituted industrial policies in the past out of unwarranted fears of other countries’ industrial policies. The results have always imposed great costs on consumers and taxpayers and introduced significant economic distortions. …Conservatives…should learn about the failed United States industrial policies of the 1980s, which were responses to the Japanese government’s attempt to dominate key consumer electronics technologies. These efforts worked neither in Japan nor in the United States. The past has taught us that industrial policies fail often because they favor existing industries that are well connected politically at the expense of would-be entrepreneurs… We shouldn’t allow fear-mongering to hobble America’s free enterprise system.

…I thought we learned this lesson after many American intellectuals, economists and politicians were proven spectacularly wrong in predicting that the Soviet Union would become an economic rival. …government officials cannot outperform the market at picking winners. In practice it ends up picking losers or hindering the abilities of the winners to achieve their greatest potential. Central planning is antithetical to innovation, as is already visible in China. …the United States has instituted industrial policies in the past out of unwarranted fears of other countries’ industrial policies. The results have always imposed great costs on consumers and taxpayers and introduced significant economic distortions. …Conservatives…should learn about the failed United States industrial policies of the 1980s, which were responses to the Japanese government’s attempt to dominate key consumer electronics technologies. These efforts worked neither in Japan nor in the United States. The past has taught us that industrial policies fail often because they favor existing industries that are well connected politically at the expense of would-be entrepreneurs… We shouldn’t allow fear-mongering to hobble America’s free enterprise system.

Amen.

My modest contribution to this discussion is to share one of my experiences as a relative newcomer to D.C. in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

I had to fight all sorts of people who said that Japan was eating our lunch and that the United States needed industrial policy.

I kept pointing out that Japan deserved some praise for its post-WWII shift to markets, but that the country’s economy was being undermined by corporatism, intervention, and industrial policy.

I kept pointing out that Japan deserved some praise for its post-WWII shift to markets, but that the country’s economy was being undermined by corporatism, intervention, and industrial policy.

At the time, I remember being mocked for my supposed naivete. But the past 30 years have proven me right.

Now it’s deja vu all over again, as Yogi Berra might say.

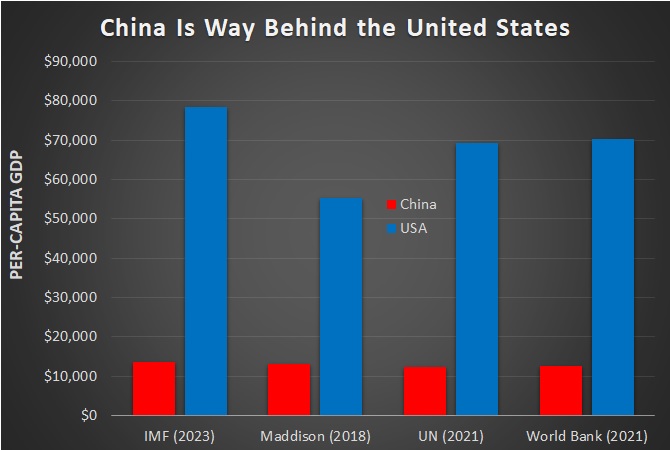

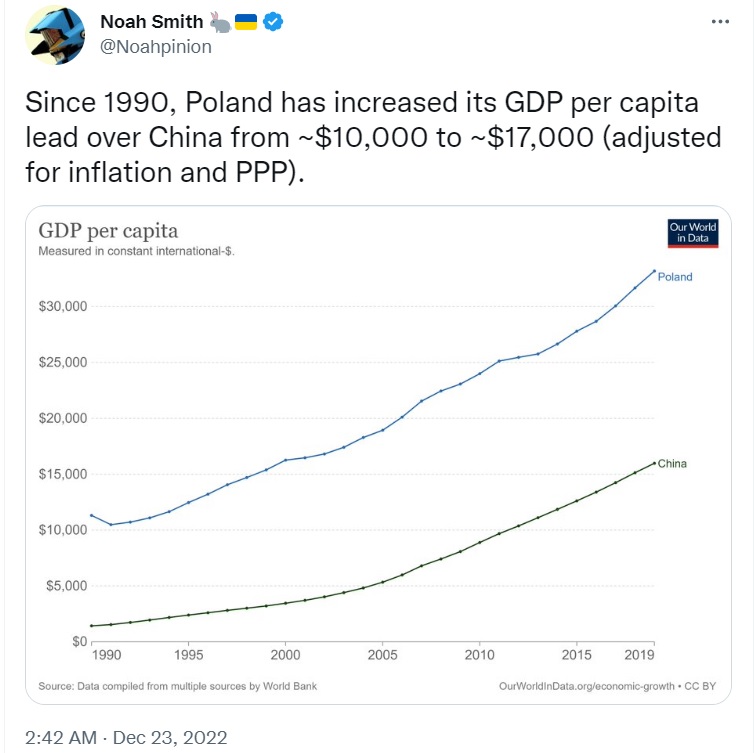

Except now China is the bogeyman. Which doesn’t make much sense since China lags behind the United States far more than Japan lagged the U.S. in the 1980s (per-capita output in China, at best, in only one-fourth of American levels).

And China will never catch the U.S. if it relies on industrial policy instead of pro-market reform.

So why should American policy makers copy China’s mistakes?

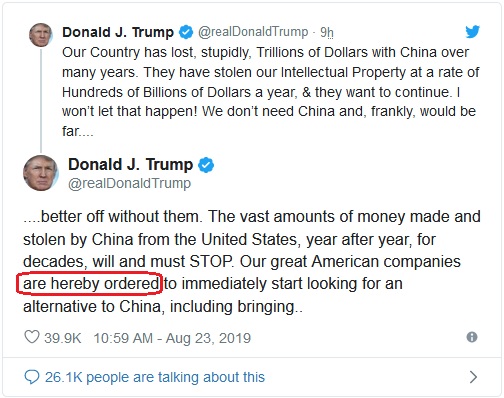

P.S. There is a separate issue involving national security, where there may be legitimate reasons to deny China access to high-end technology or to make sure American defense firms don’t have to rely on China for inputs. But that’s not an argument for industrial policy.

P.P.S. There is a separate issue involving trade, where there may be legitimate reasons to pressure China so that it competes fairly and behaves honorably. But that’s not an argument for industrial policy.

Read Full Post »

because rich countries are rich.

because rich countries are rich.which he accused of holding back developing nations with trade sanctions and demands for political reform. …His signature project has ballooned into a $1 trillion endeavor, but it is still only a loosely coordinated network of power plants, ports, roads and railways. It has generated significant controversy, with host countries like Sri L anka and Nepal struggling to overcome mounting debt distress… A white paper released last week lays out Xi’s bold claim that China, through the Belt and Road, offers a new route to wealth for nations disillusioned with Western-led globalization, and promises a greater share of spoils for the Global South if the world develops according to Beijing’s playbook. “It is no longer acceptable that only a few countries dominate world economic development, control economic rules, and enjoy development fruits,” the paper stated.