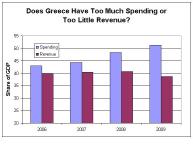

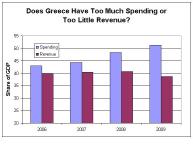

In 2008, government spending consumed 50.9 percent of economic output in Greece according to OECD fiscal data. That same year, Greece’s score from Economic Freedom of the World was 7.12 (on a 0-10 scale),  which was rather poor for a supposedly developed country and only #60 for all nations.

which was rather poor for a supposedly developed country and only #60 for all nations.

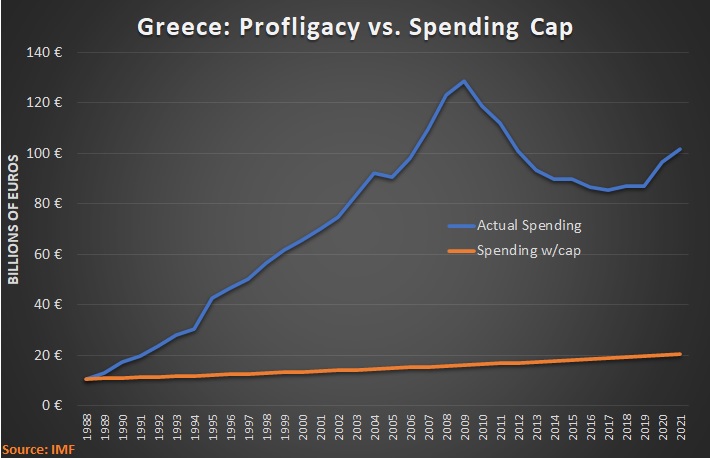

Then the fiscal crisis hit and Greece supposedly has atoned for its profligacy and gone through a tough period of “austerity” to reduce the burden of government spending and cut back on onerous levels of bureaucracy and red tape.

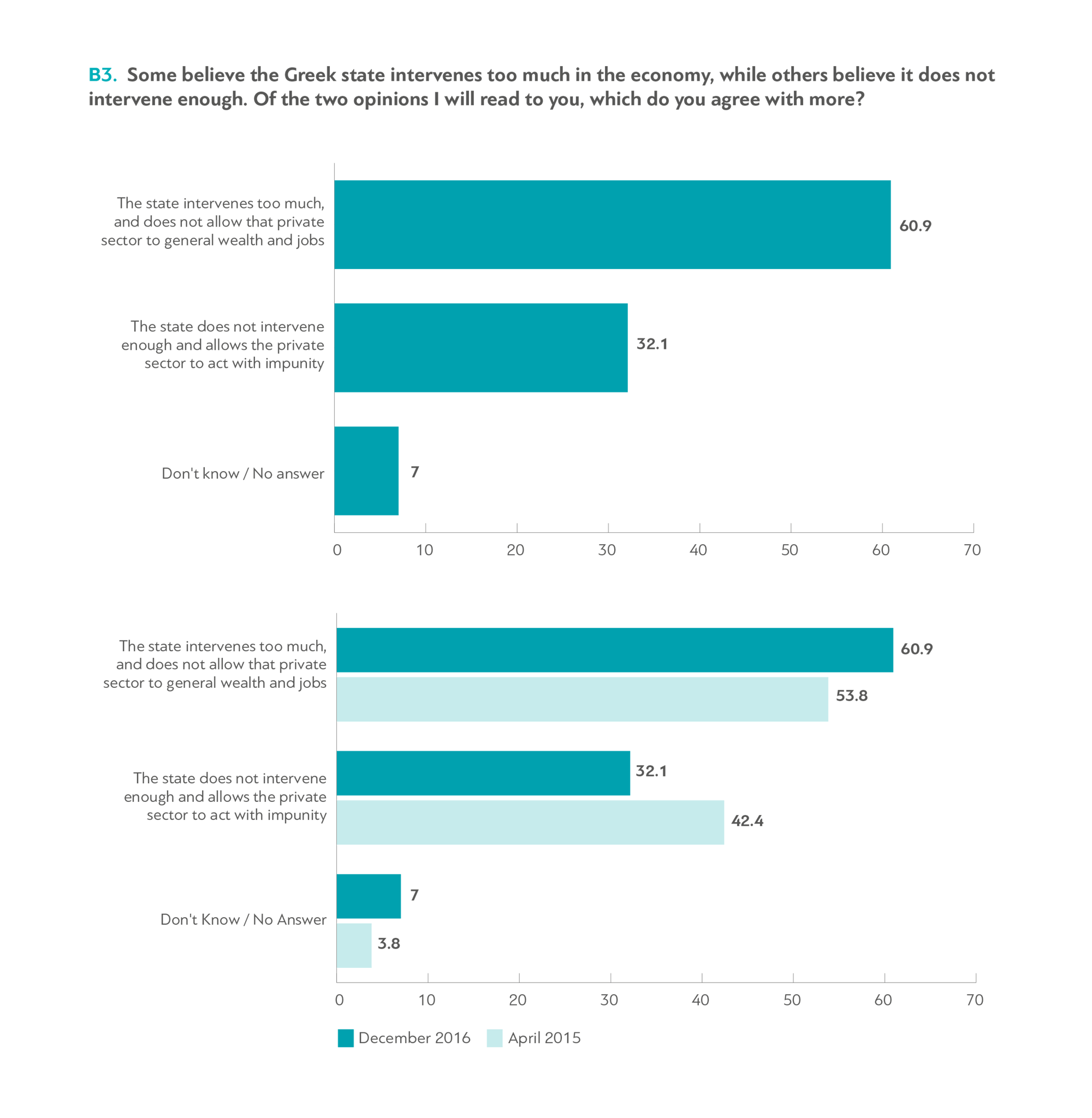

How much progress has occurred? Have Greek politicians, with the help of the European Commission, International Monetary Fund, and European Central Bank (the infamous “troika”), scaled back government and freed up the private sector?

Nope.

The OECD data shows that the burden of government spending is now 53.1 percent of economic output. And the latest data from Economic Freedom of the World shows that Greece’s score has dropped to 6.93 (dropping the country to #86 in the rankings).

In other words, Greece suffered a crisis caused by too much government and too much statism and the politicians (along with outside “experts”) decided that the solution was to….drum roll, please…increase the relative size and scope of government.

As one Greek observer noted in a column for CapX, this has not been a very successful recipe.

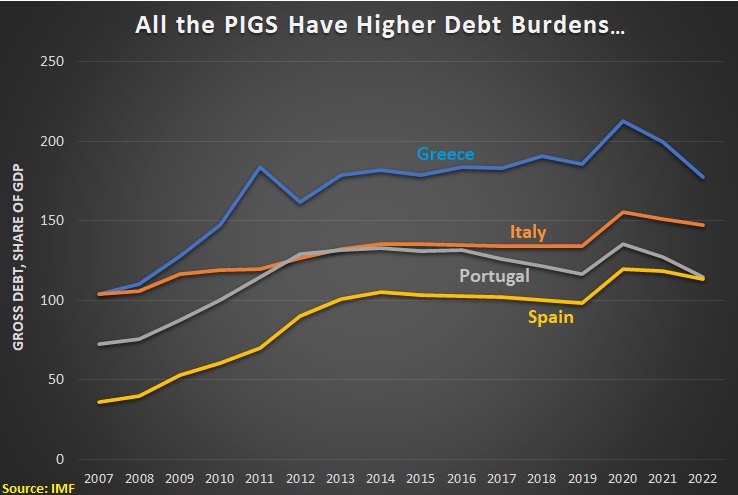

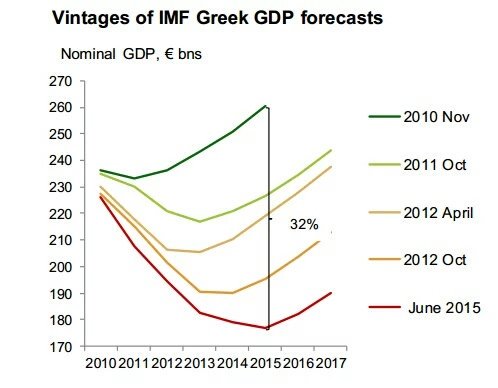

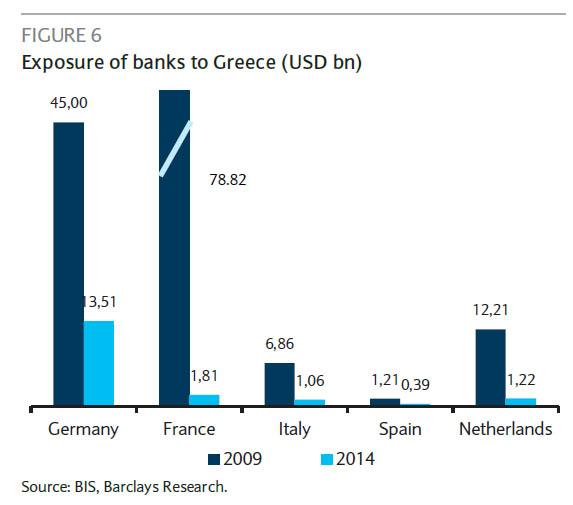

…how has the Troika been performing? 3 adjustment programs, 12 reviews, 220 billion Euros and 7 years down the road, the results are abysmal: 179% debt, 0% growth, 25.1% unemployment.

To be fair, there has been some spending restraint since the crisis began. In some years, the budget even shrank. The problem, though, is that the private sector has been battered by huge tax increases, thus crippling incentive to create jobs and growth.

If you want to get a sense of what’s happening, this New York Times story is a very sobering example. Apparently the tax burden is so oppressive that people don’t want to inherit property.

At law courts throughout Greece, people are lining up to file papers renouncing their inheritance. …they are turning their backs on what used to be a pillar of Greece’s economy and society: real estate. …In 2013, two years after a property tax was introduced (previously, real estate tax revenue came mainly from transfers or conveyance taxes), 29,200 people declined to accept their inheritance, according to the Justice Ministry. In 2015, the number had climbed to 45,627, an increase of 56 percent in two years. Reports from across the country suggest that this year, too, large numbers of people are refusing to inherit. …People once hoped that if they came into property they could sell it and live easier; now they fear that they will be unable to sell it and the taxes will drag them down. …After many years in which only very valuable properties were taxed, many Greeks went from paying almost no taxes on real estate to not having enough money to pay. In 2010, property taxes accounted for 0.26 percent of gross domestic product, while this year they are around 2 percent, according to state budget figures. …Arrears in tax payments at the end of September were at 92.8 billion euros and keep increasing by about 1 billion each month.

But give Greek politicians credit for a perverse form of perseverance. They’re doing everything they can to squeeze even more money from oppressed taxpayers. Indeed, the U.K.-based Times reports that they’re even spying on social media to see if people have lifestyles that seem extravagant compared to the income they report to tax police.

Finance ministry officials said that an operation named “24 hours” will monitor about 1.8 million Greeks believed to be declaring an income inconsistent with their lavish lifestyles they enjoy and display on websites. Trifon Alexiades, the deputy finance minister, said: “It may sound ludicrous, but this is a serious effort to crosscheck information about those suspected of concealing wealth.” Tax authorities will begin operating software in September for a month-long trial. “Under this new scheme, auditors will be able to access taxpayers’ Facebook, Twitter and Instagram accounts to extract information and details of assets that may not have declared,” a Greek news site reported.

Ugh, I guess this is the kind of policy you get with you mix French-style economic advice and German-style tax enforcement.  Geesh, maybe the IRS isn’t so bad after all.

Geesh, maybe the IRS isn’t so bad after all.

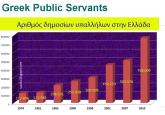

And it doesn’t seem the current left-wing government is learning from all these mistakes. The EU Observer reports that it wants to make the nation’s infamous bureaucracy even bigger.

Alexis Tsipras’ Greek government plans to hire 20,000 civil servants over the next year to help Greece’s austerity hit education and health services. Government officials believe that the hiring will not run into objections from representatives of Greece’s international creditors, Kathimerini newspaper reports.

By the way, Greek politicians think more spending is the right recipe, even if it means more spending in other nations. Here’s some of what was reported back in June by Bloomberg.

Greek Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos urged Germany to take advantage of record-low borrowing costs and invest more to spur the economy, saying Europe should seize the chance to modernize its infrastructure. …Failure to provide the euro area with a Keynesian-type stimulus would risk leaving the region with insufficient infrastructure, said Tsakalotos, whose country has the biggest ratio of debt to gross domestic product in Europe. European Union budget rules should be changed so that investment spending is excluded when calculating whether countries have met deficit targets, he said.

I guess this could be called an example of misery-loves-company economic advice. Germany has actually been complying with Mitchell’s Golden Rule in recent years (and part of last decade also) and its economy is in decent shape.

But Greek politicians are basically saying, “Hey, you should be more like us.”

Heck, the Prime Minister of Greece already is trying to create a coalition of fiscally mismanaged nations.

Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras on Thursday invited leaders of six southern EU states to meet…in a bid to form a strong southern alliance and counter the stance of countries in Northern Europe. Athens News Agency reports the states invited will include France, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Malta.

The article doesn’t say what this alliance would accomplish, though presumably Tsipras hopes it will be a unified voice for more handouts. Maybe it can agitate for something really crazy such as eurobonds.

I’m also amused that Greek officials think businesses will invest in a highly-taxed economy merely if politicians promise not to raise taxes even further. I’m not joking. Here are some excerpts from a Reuters report.

Greece is offering big investors more than a decade of no increases in their taxes, in an effort to promote entrepreneurship in a country struggling to return to growth after almost seven years of recession. …Under the law, investment plans exceeding 20 million euros and creating at least 40 new jobs could choose a stable tax regime with no tax increases for 12 years once the investment is concluded.

By the way, just in case you think promising not to go even further in the wrong direction is akin to a step in the right direction, you need to keep reading the article because you’ll discover the plan is based on cronyism.

Alternatively, they can apply for a subsidy, amounting to 10 percent of the plan and up to 5 million euros.

And if you want to understand why Greece is hopeless, check out what the Economy Minister said about how any new investments will get “quick” approval.

Stathakis said that Athens will seek to shorten approval time for investment plans to three months instead of the two to three years it takes now.

Needless to say, the approval time in a market economy is zero because people don’t have to get permission from bureaucrats before creating jobs and investing money.

But in Greece, if you curry favor with the mandarins, you’ll “only” have to wait three months. I guess that’s to be expected in a nation where bureaucrats demand stool samples before you can set up an online company.

And since we’re on the topic of regulation and red tape, this is a good time to point out that the Greek government apparently is good at passing laws to liberalize the economy but not very good at implementing them.

Guy Verhofstadt, leader of the European Liberals and Democrats, is very critical… “Greece is passing a lot of legislation, but is not implementing it. It is shocking to see that 74% of the legislation that has been adopted since the first bailout package has never been implemented.”

But let’s look at the bright side. This means 26 percent has been implemented. Of course, that 26 percent presumably includes all the tax increases.

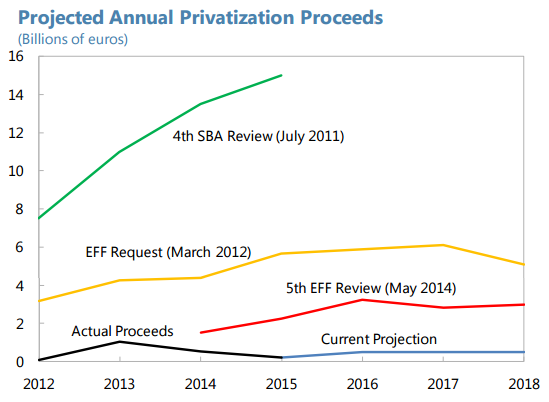

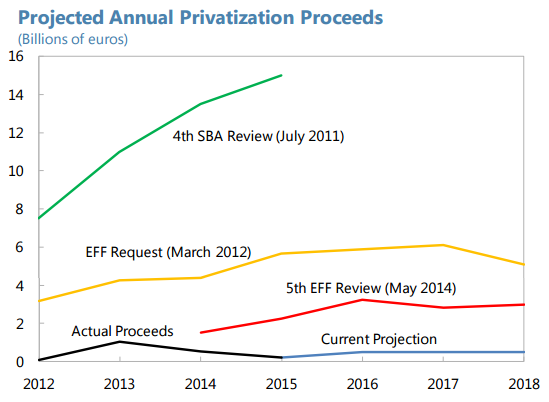

In any event, Greece has a miserable track record when it comes to following through on commitments to reduce state intervention.  The government was supposed to engage in sweeping privatizations, but the gap between projections and performance is enormous.

The government was supposed to engage in sweeping privatizations, but the gap between projections and performance is enormous.

Last but not least, I’ve always thought the ultimate sign of incompetence is when a government can’t even waste money effectively. I’ve already noted that Japan and the U.K. have met this test, and now I can add Greece to the list.

Hundreds of millions of available EU funds have yet to be used by the Greek state to help migrants and refugees. Administrative bottlenecks on the Greek side mean that…The European Commission…will soon be sending someone to Athens to help the government resolve its issues in an effort to better spend the money.

You may be wondering what’s the purpose of today’s attack on Greece. Is it because I think poorly of Greeks? Well, I despise Greek moochers, but I have the same view of French moochers and American moochers, so that’s not the answer.

You also may be thinking this is just another excuse for me to say “I told you so” about the failure of bailouts. Sure, I’m happy to pat myself on the back, even though any non-comatose person should have known bad things were going to happen.

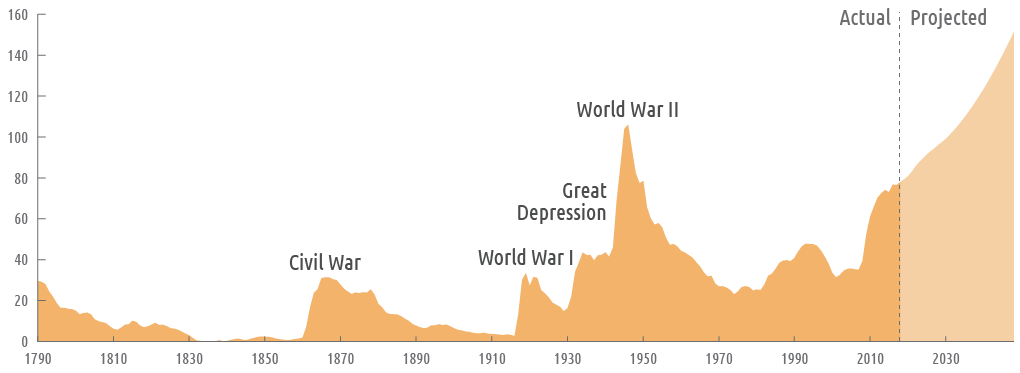

My real goal is to warn that the miserable results in Greece will be replicated if we try the same policy in America. There are several states that are on a very bad trajectory, such as California and Illinois. I don’t know if things will blow up during the next recession or afterwards, but if there’s any hope of forcing politicians to make sensible choices in Sacramento and Springfield, it will be very important for Washington to reject all pleas for handouts.

Likewise, pension funds for state and local government bureaucrats are ticking time bombs. Once again, prudent reforms will only be possible if politicians conclude that there’s no hope for bailouts from Uncle Sam.

The bottom line is that politicians will continue to make mistakes if they can make other people pay the price. That’s today lesson.

P.S. Even though Greece’s debt is sustainable, I would prefer a default if it meant no more bailouts. Yes, Greek politicians would be reneging on their past obligations, but the good news is that they wouldn’t be able to borrow any more money and (hopefully) would have no choice but to copy Latvia and adopt good policy.

P.P.S. Though it’s an open question whether Greece can be saved. Many productive people already have escaped the nation and most of the ones who have stayed are part of the problem.

P.P.P.S. To offset the grim message of today’s column, let’s close with some Greek-related humor.

This cartoon is quite good, but this this one is my favorite. And the final cartoon in this post also has a Greek theme.

This cartoon is quite good, but this this one is my favorite. And the final cartoon in this post also has a Greek theme.

We also have a couple of videos. The first one features a video about…well, I’m not sure, but we’ll call it a European romantic comedy and the second one features a Greek comic pontificating about Germany.

Last but not least, here are some very un-PC maps of how various peoples – including the Greeks – view different European nations.

Read Full Post »

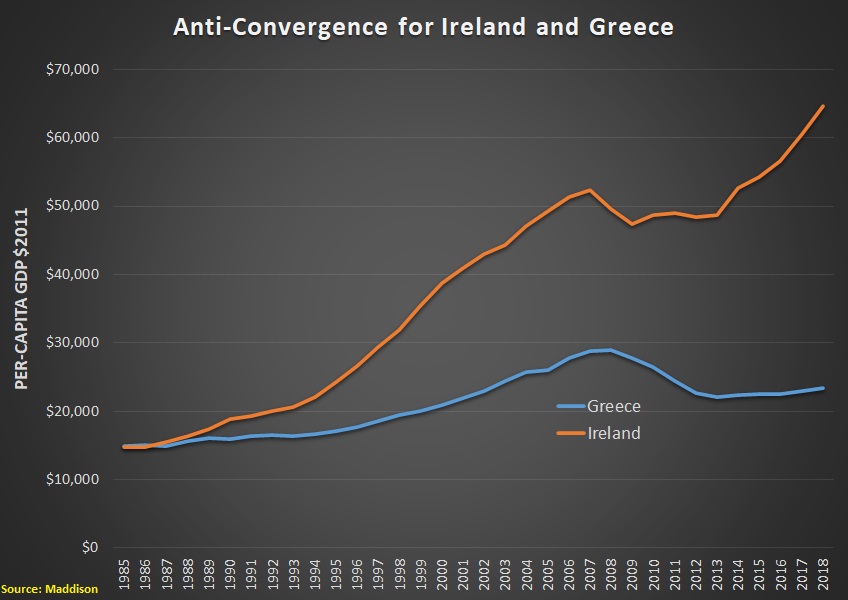

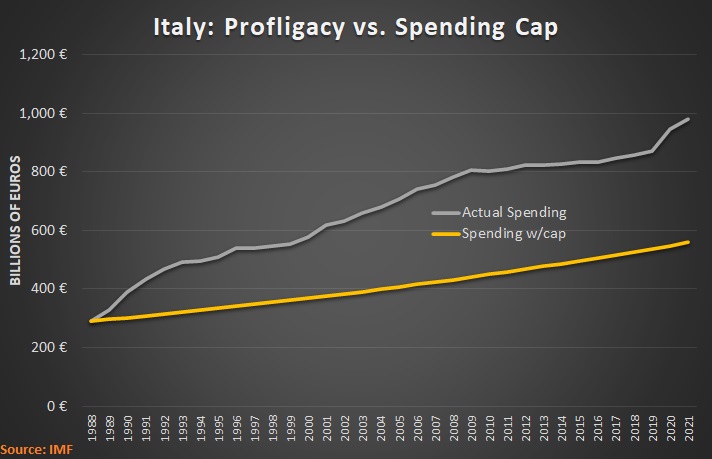

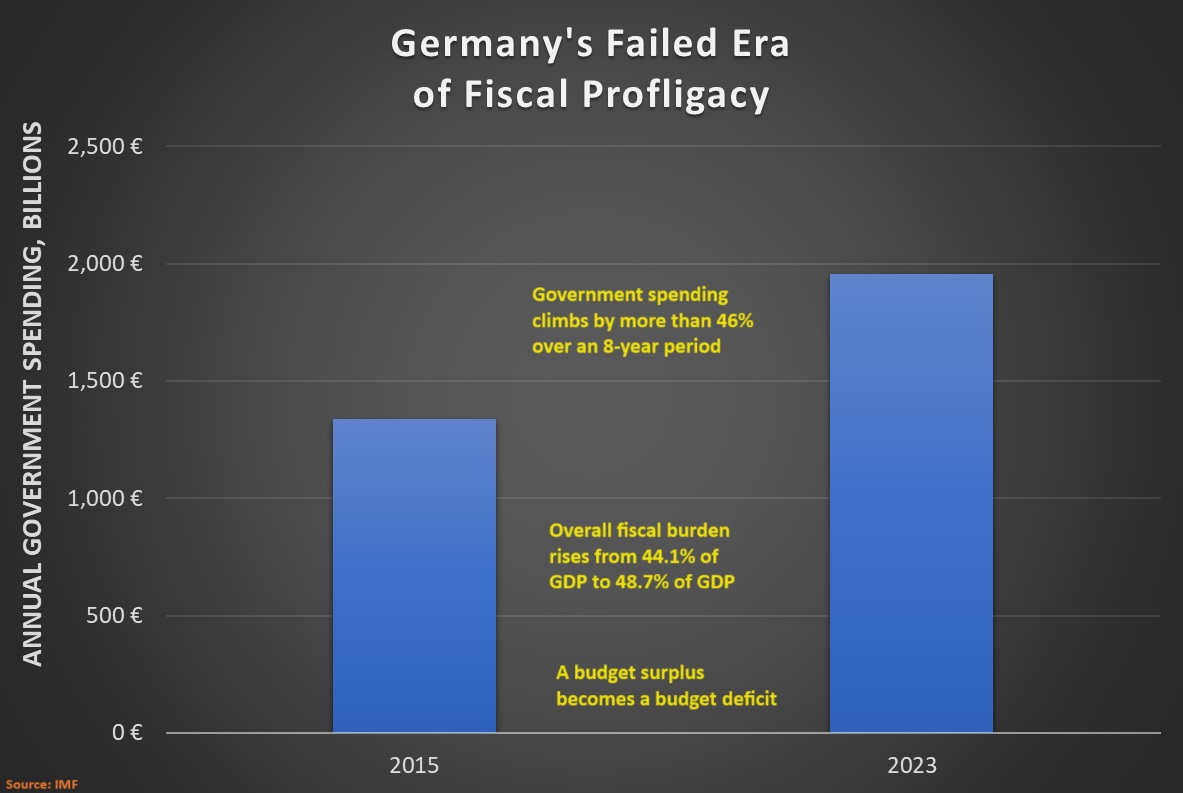

Over the past eight years, government spending has grown much faster than the private sector, thus violating the Golden Rule of fiscal policy.

Over the past eight years, government spending has grown much faster than the private sector, thus violating the Golden Rule of fiscal policy.In a reversal of fortunes, the laggards have become leaders. Greece, Spain and Portugal grew in 2023 more than twice as fast as the eurozone average. Italy was not far behind. …southern European countries made crucial changes that have attracted investors, revived growth and…reversed record-high unemployment. Governments cut red tape and corporate taxes to stimulate business and pushed through changes to their once-rigid labor markets, including making it easier for employers to hire and fire workers.