Early in the Biden years, I wrote a three-part series (here, here, and here) to explain why a global minimum tax on companies is a bad idea.

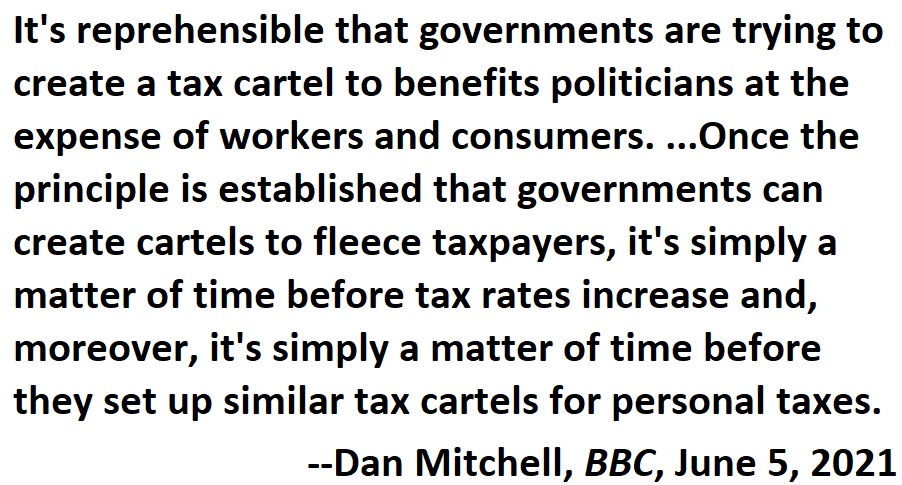

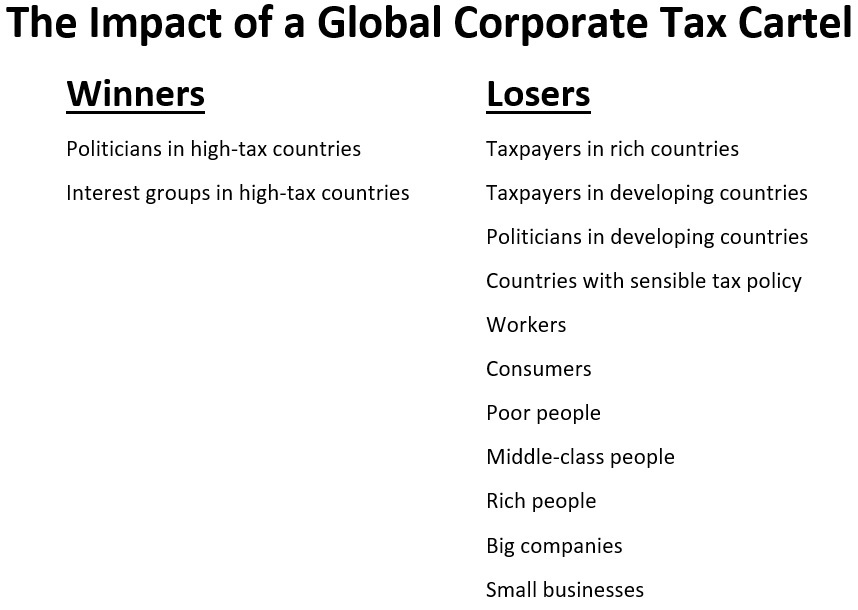

As I told the BBC back in 2021, this proposed tax cartel is a scheme to increase the tax burden and will be very bad news for workers, consumers, and shareholders.

Folks on the left, however, like the idea of politicians having more power and money. So they defend the cartel, which was organized by the bureaucrats at the Paris-based Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

In a column for the Washington Post, Natasha Sarin and Kimberly Clausing try to defend the OECD’s tax harmonization scheme.

Republican lawmakers…are attacking…the global minimum tax. …We both worked at Treasury when the agreement was forged, and we believe strongly that it represents an important step forward.

…the deal brings together more than 135 jurisdictions, representing about 95 percent of the world economy, to stem the damaging race-to-the-bottom competition that allows the world’s largest multinational companies to shift income offshore rather than pay their fair share at home. The key mechanism is a 15 percent minimum tax — hence the name — and the agreement should be applauded, not pilloried.

The column lists five claims supposedly made by congressional Republicans and the authors then give their response.

For purposes of today’s column, I’ll show their response and then give my response. Sort of a debunking of the debunking, except my main argument is that they are being evasive rather than dishonest.

1st Republican claim: “The agreement threatens U.S. tax sovereignty.”

Here’s how Sarin and Clausing respond.

In the past, some lawmakers have cautioned that we can’t afford to tax mobile corporate income because that income can simply be shifted to countries that offer lower rates. But with a universal 15 percent minimum rate, Congress’s options widen, giving policymakers the freedom to choose rates that align with the nation’s fiscal priorities.

The truth: The authors make it seem like this is a semantic issue – i.e., is a tax cartel a surrender of sovereignty or an expression of sovereignty. But that’s not important. What matters is whether it is good policy for governments to conspire against taxpayers. The answer unambiguously is no.

2nd Republican claim: “The agreement is an unconstitutional giveaway to foreign governments.”

Here is their response.

Here’s what the deal actually does: Say France implements the minimum tax, but a U.S. multinational with a French subsidiary retains the abileity to move income from France to a low- or no-tax jurisdiction to avoid it. France could then impose a tax topping up the effective rate to 15 percent.

The truth: I have no idea about the legality or constitutionality of the tax cartel, but the authors once again dodge the real issue, which is whether it is a good idea to to divert more money from the productive sector of the economy so that politicians (regardless of their location) can spend more.

3rd Republican claim: “The agreement harms the competitiveness of U.S. businesses.”

Their response:

By raising the “bottom” from zero to 15 percent, and in a way that affects companies regardless of the location of their headquarters, the agreement is a giant step toward a more level playing field, so U.S. businesses don’t end up at a competitive disadvantage.

The truth: Politicians (and the authors!) openly brag about how a global tax cartel will enable governments to grab ever-larger shares of business income. Of course this will harm American companies.

4th Republican claim: “The agreement hurts workers by harming the companies they work for.”

Their response:

A global minimum tax will help the U.S. government create a more balanced system that taxes the most profitable companies in the world at rates that are closer to what middle-class families pay. This means workers will shoulder less of the tax burden themselves.

The truth: As every public finance economist knows, only people pay taxes. Any tax on a business is really a tax on workers, consumers and shareholders. To make matters worse, the higher business tax burdens will reduce investment, which will lower productivity, and thus translate into lower wages for workers.

5th Republican claim: “The agreement harms U.S. government revenue.”

Their response:

Republican lawmakers have argued that the federal government will lose revenue once foreign governments are emboldened to tax U.S. companies. But…the global agreement makes the corporate tax base less porous by reducing profit-shifting to low-tax havens. …The whole point of the agreement was to ensure that countries that want to use the corporate tax to generate revenue can do so. Indeed, the Biden administration has proposed hundreds of billions in new corporate tax revenue

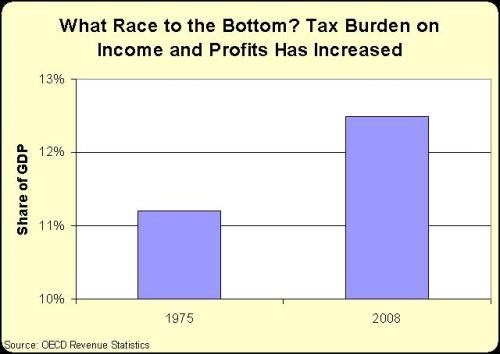

The truth: Since I want to reduce revenue for Washington, I have mixed feelings about this final point. I’ll simply note that the OECD’s own data shows that the global shift to lower tax rates has not led to lower revenues. Heck, the OECD has also produced research confirming there’s a strong Laffer Curve for corporate taxes.

The bottom line is that Sarin and Clausing believe in higher taxes and bigger government.

So it is understandable that they support global tax cartels. Unfortunately, they never explain in their column why a bigger burden of government is desirable.

So it is understandable that they support global tax cartels. Unfortunately, they never explain in their column why a bigger burden of government is desirable.

I suspect their evasiveness is because the evidence (even from left-leaning international bureaucracies) is not on their side.

So let’s hope this global tax cartel falls apart and we can have a new era of tax competition.

P.S. Joe Biden deserves criticism for supporting the OECD’s proposed tax cartel, but let’s not forget that Donald Trump also was very bad on the issue.