I’m in Hong Kong for series of meeting and briefings on various economic and policy issues.

As you can imagine, I’m a huge fan of the jurisdiction’s simple 15 percent flat tax. It’s basically about as close to a pure flat tax as anyplace in the world. There is zero double taxation of income that is saved and invested.

That’s not an exaggeration. You don’t get double taxed on the interest you earn on your bank balances and other financial accounts. There’s no capital gains tax. There’s no death tax. And there’s no double taxation of dividends.

That’s not an exaggeration. You don’t get double taxed on the interest you earn on your bank balances and other financial accounts. There’s no capital gains tax. There’s no death tax. And there’s no double taxation of dividends.

There are only a few deviations from a pure flat tax that even merit a mention. First, taxpayers with modest amounts of income don’t have to use the flat tax system. Instead, they can opt for a “progressive” tax system that has a top rate of 17 percent, but also has tax rates of 2 percent and 7 percent, and 12 percent.

Imagine, taxpayers getting to choose the system that works best for them, instead of the government forcing them into the system that requires the highest payment!

The other deviations are that businesses are not always allowed full expensing of business investment, and there also are a handful of deductions.

All things considered, though, Hong Kong gets almost everything right on tax policy, whereas the United States gets a majority of things wrong.

Oh, and I should mention that there are no payroll taxes in Hong Kong. Nor is there a value-added tax.

That’s all very impressive, but let’s actually focus on something that may be even more remarkable about Hong Kong.

It currently has a modest-sized government, with spending consuming less than 20 percent of economic output. That’s not as good as the United States 100 years ago, but it’s far better than where America is today.

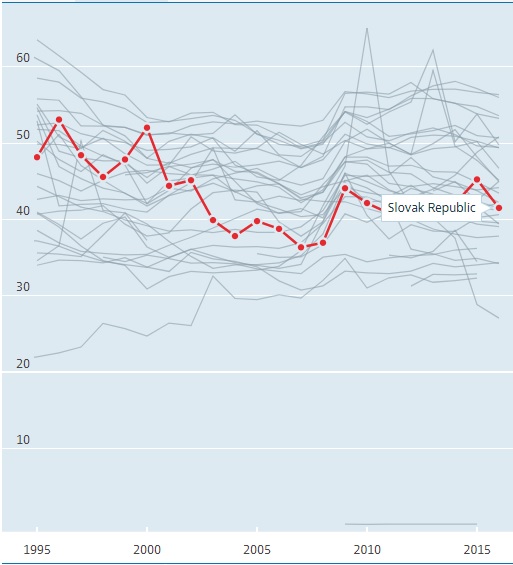

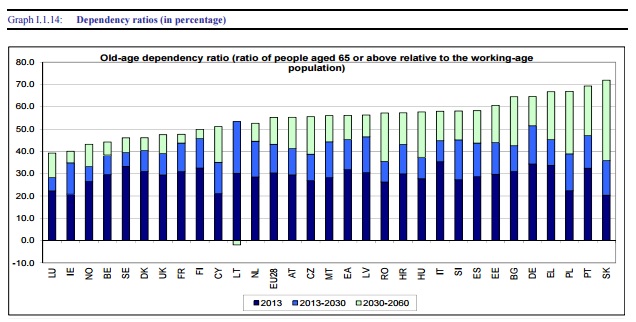

That being said, Hong Kong has some major challenges. I’ve explained before that demographic changes will put pressure on fiscal policy in America, but demographic change is far more profound in Hong Kong.

As you can see from this data, it has the seventh-highest level of life expectancy in the world.

That’s good news, of course, but it does mean a lot of fiscal pressure, even for a jurisdiction that is justly famous for its very small welfare state.

But then you have to consider the fact that Hong Kong also has the fourth-lowest birthrate in the entire world.

In other words, Hong Kong faces a perfect storm of demographics. More and more non-working elderly over time, combined with fewer and fewer taxpayers to pull the wagon.

Given these unfriendly numbers, the Hong Kong government put together a working group to look at long-run fiscal issues.

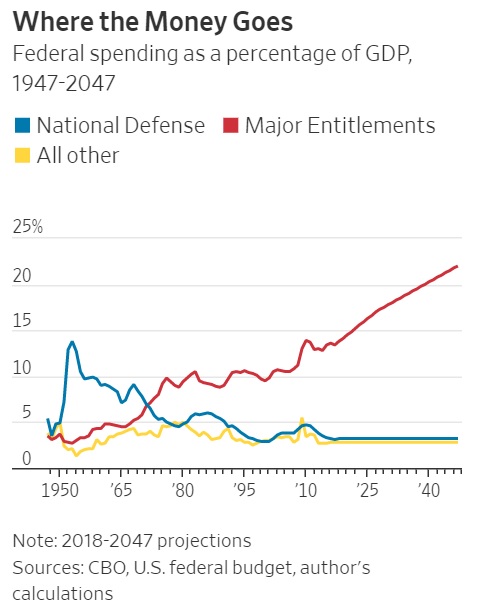

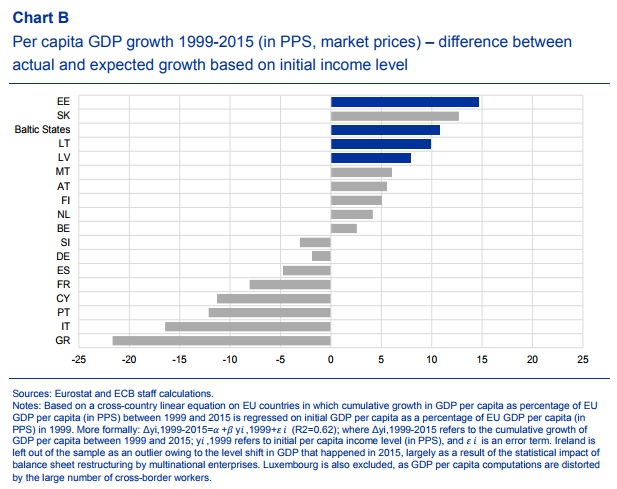

In its recent report, the group presented a fiscal forecast that shows how the burden of government spending will slowly climb to nearly 24 percent of GDP over the next 25 years.

Here’s a chart showing actual data starting in the late 1990s and then projections until 2042.

To those of us from North America and Western Europe, where the overall burden of government spending, on average, consumes more than 40 percent of economic output, it seems like Hong Kong has a trivial problem.

But it’s still a problem and something has to change. Hong Kong could finance a bigger public sector by dipping into its large reserves (currently the jurisdiction has saved enough money to finance about two years of government spending) or by increasing the tax burden.

But hopefully Hong Kong will abide by Article 107 of its Basic Law (its constitution) and limit government spending so that it doesn’t grow faster than the private economy.

But hopefully Hong Kong will abide by Article 107 of its Basic Law (its constitution) and limit government spending so that it doesn’t grow faster than the private economy.

And there are some positive signs.

About 15 years ago, Hong Kong set up a system of private retirement accounts in order to create a self-funded source of retirement income.

Based on a recent government report on retirement income, here are some key features of this Mandatory Provident Fund (MPF) system.

The MPF System is an employment-based, privately-managed mandatory defined contribution system. …Employers are required under the Mandatory Provident Fund Schemes Ordinance (Cap. 485) to arrange for their employees aged 18 or above but under 65 to join… The MPF System has been implemented for 15 years only. …about 2.55 million employees are enrolled in MPF schemes, representing 100% of the employees required by law to join the schemes. This is a very high rate by international standards. In addition, another 210 000 self-employed persons are also scheme members. …An employer and an employee are each required to contribute 5% of the relevant employee’s income… As at end October 2015, MPF assets had increased to $594.2 billion, of which about $123.1 billion were investment returns.

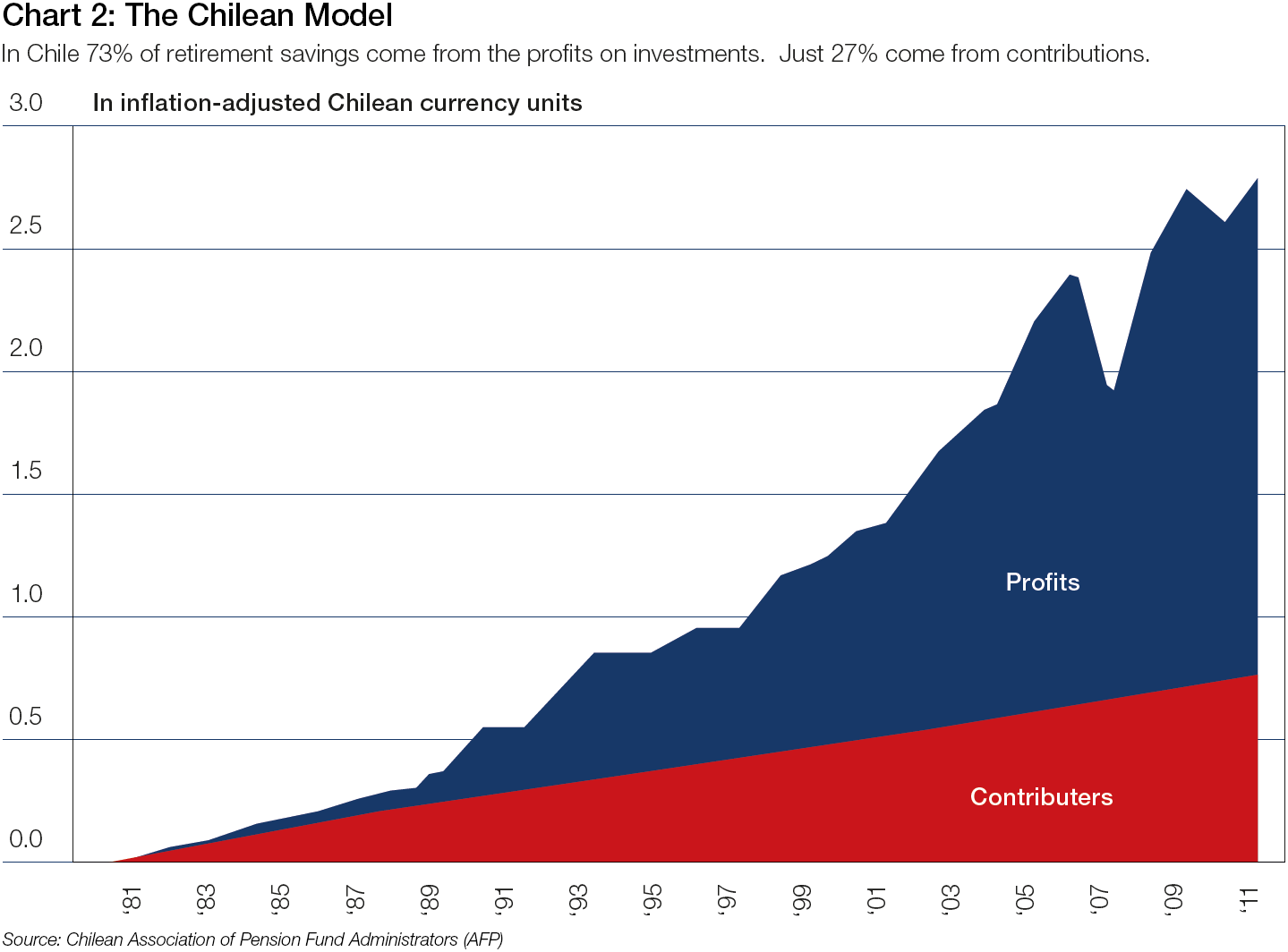

Here’s a chart from the report, showing the cumulative growth of assets, based on both contributions and investment returns.

Keep in mind, though, that it takes 7.8 Hong Kong dollars to equal 1 U.S. dollar, so $594.2 billion is not nearly as large as it sounds.

In part, this is because the system isn’t yet mature. Workers have only been making contributions from 15 years, while a working lifetime is 40-45 years.

But there also are concerns that the level of mandatory saving is insufficient. Here’s additional language from the report, which cites the private retirement systems in Australia and Denmark.

There are views that the contribution rate or the maximum relevant income level should be raised to strengthen the retirement protection function of the MPF System. Take the privately-managed mandatory occupational contributory pension plans in Denmark and Australia as examples. In Denmark, employers and employees generally contribute a total of 9% to 17%. In Australia, only employers make contributions and the contribution rate will be raised progressively from 9% in 2013 to the present 9.5% and further to 12% in 2025.

I’m personally agnostic on the precise level of mandatory savings. My goal is simply to shrink tax-and-transfer entitlement programs, particularly before demographic changes lead to a larger burden of government spending.

And since I have great fondness for Hong Kong (how can you not get a thrill up your leg about a jurisdiction that routinely gets the highest score in Economic Freedom of the World?), I want it to remain a beacon for advocates of economic liberty.

about a jurisdiction that routinely gets the highest score in Economic Freedom of the World?), I want it to remain a beacon for advocates of economic liberty.

P.S. Lest anyone think I’m being too fawning, Hong Kong has several policies that are misguided. Public housing is pervasive, there’s government-run healthcare, and one peculiar legacy of British rule is that only one piece of land is privately owned. Fixing these warts would make Hong Kong even more vibrant.

P.P.S. Another quirky feature of Hong Kong policy is that currency is issued by private banks. If you pull a $20 bill from your wallet, you’ll see that it was printed by HSBC, Standard Chartered, or Bank of China. Unfortunately, this isn’t because Hong Kong has a market-driven system of competing currencies. But it does have a currency board, which – by standards of government-controlled monetary systems – is one of the least-worst options. Of course, that means Hong Kong’s money is only as good as the currency to which it’s linked. And since the Hong Kong dollar is pegged to the U.S. dollar, that might be a cause for long-run concern.

Read Full Post »

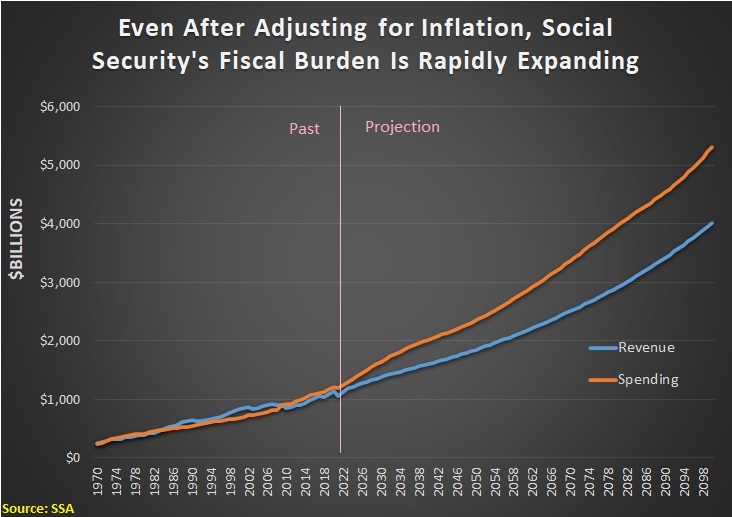

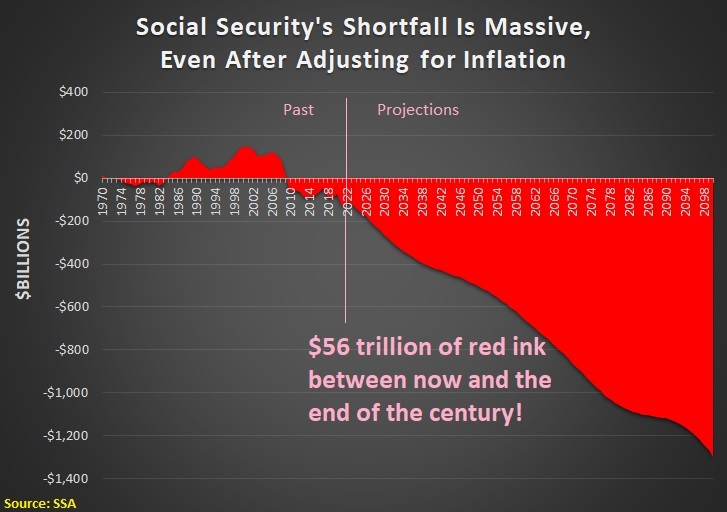

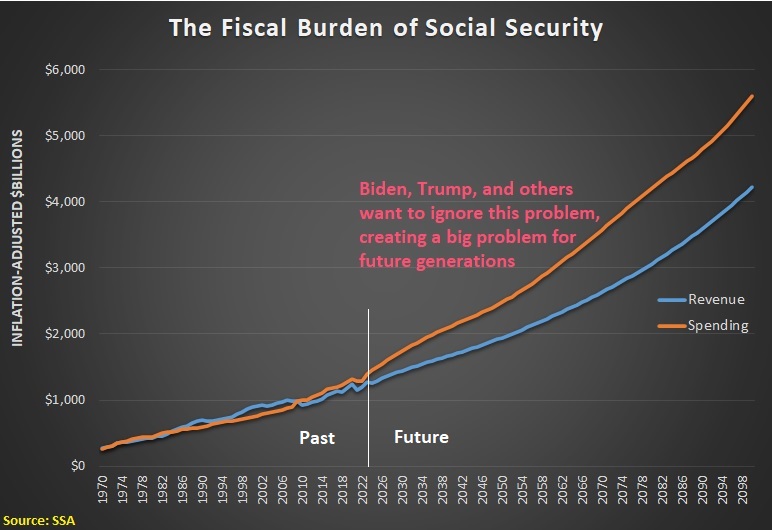

But even if this demographic problem didn’t exist, there is the underlying flaw of a retirement system based on tax-and-spend (or debt-and-spend) rather than wealth accumulation.

But even if this demographic problem didn’t exist, there is the underlying flaw of a retirement system based on tax-and-spend (or debt-and-spend) rather than wealth accumulation.Revenues saved from repealing the retirement saving tax preferences could be reallocated to address the majority of Social Security’s long-term funding gap. …an opportunity to use taxpayer resources more productively. …the case is strong for eliminating the current tax expenditures on retirement plans, and using the increase in tax revenues to address Social Security’s long-term financing shortfall. …Tax expenditures for employer-sponsored retirement plans are expensive – costing about $185 billion in 2020. … reducing tax expenditures for retirement plans could be an effective way to help address other pressing demands on the federal budget, such as Social Security’s financing shortfall.