I first started complaining about bad economic policy in Ukraine nearly 10 years ago.

But since I routinely criticize bad policy around the world, that was not special  (and since politicians at home and abroad generally ignore my advice, it also was not effective).

(and since politicians at home and abroad generally ignore my advice, it also was not effective).

However, a silver lining to the dark cloud of Putin’s invasion is that there is now a lot of serious discussion of how Ukraine can prosper once the war is over.

I wrote last year that Ukraine could simply adopt the best policies of other European nations, an approach that overnight would give Ukraine one of the world’s freest economies.

Sadly, not everyone agrees. The Washington Post editorialized on this topic and wrote that Ukraine needed massive government-to-government transfers.

Planning for Ukraine’s reconstruction needs to start now… But the staggering sums required to do the job are beyond what is financially, logistically and politically feasible for the foreseeable future. …Ukraine is already struggling to pay its short-term bills.

As the conference on Ukraine convened, aid packages to help stabilize Kyiv’s finances — including paying government and military salaries — were announced by the European Union, the United States, Britain and others. …The West hopes much of the eventual rebuilding cost will be borne by private companies hoping for profits. Yet there is little chance of that without an international effort to provide insurance against the ongoing risk of future Russian missile strikes that could lay waste to half-finished factories and office buildings.

The editorial makes a few good points, including whether private investment would materialize if there was an ongoing threat of war.  The piece also speculated about whether frozen Russian assets could be used for rebuilding.

The piece also speculated about whether frozen Russian assets could be used for rebuilding.

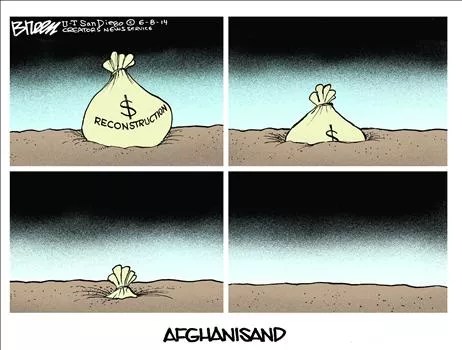

Those reasonable points, however, are offset by a mistaken assumption that foreign aid is the key.

In reality, foreign aid has a terrible track record. It largely subsidizes bigger government and enables dirigiste policy. And it makes corruption far more likely.

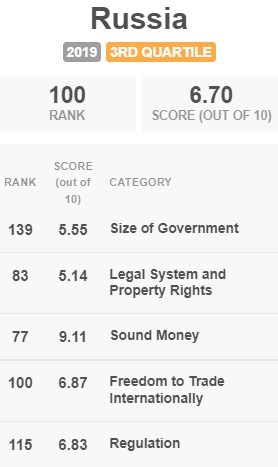

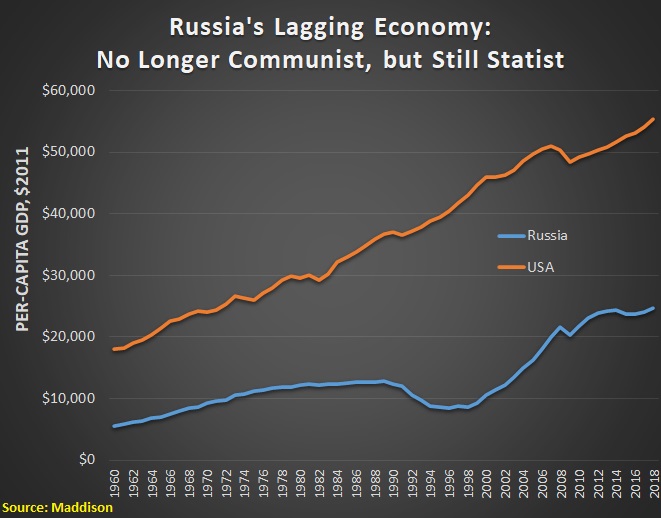

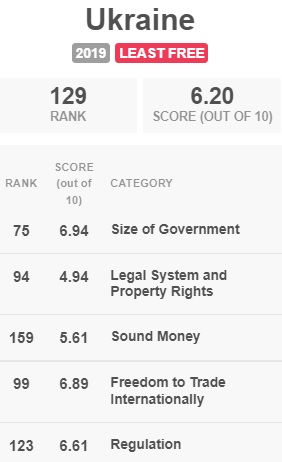

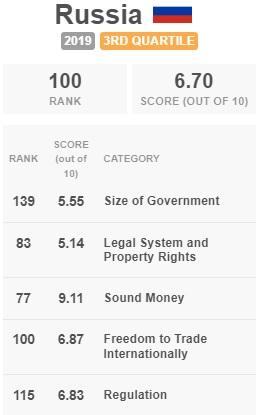

Instead of asking if there is enough money to rebuild Ukraine, ![]() the editorial should have asked if there’s enough freedom (being a thoughtful guy, I even created a more accurate title).

the editorial should have asked if there’s enough freedom (being a thoughtful guy, I even created a more accurate title).

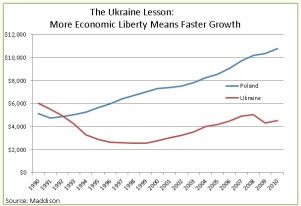

I’m not the only one thinking more economic liberty is the real solution.

Here are some excerpts from a column by Rainer Zitelmann, which was published by the Foundation for Economic Education.

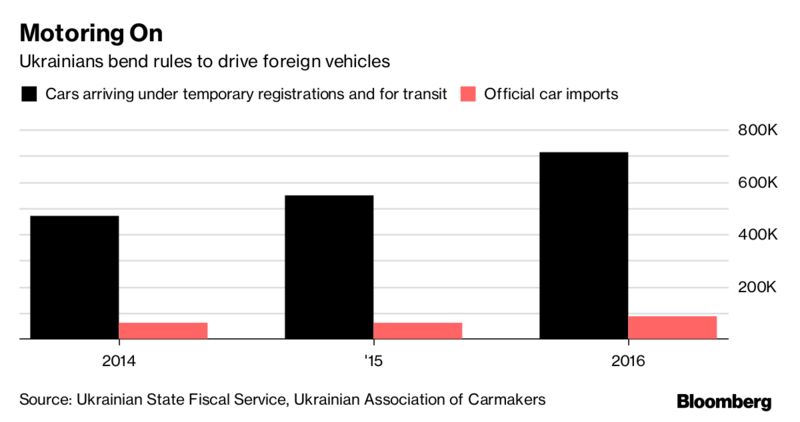

…libertarian think tanks and politicians are already making plans for the period after the war. …Maryan Zablotskyy, a Member of the Ukrainian Parliament and of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s ruling party. …Income tax in Ukraine, Zablotskyy said, was recently lowered to two percent, and numerous regulations and tariffs have been abolished.

…It is beyond extraordinary for a country to cut taxes and abolish regulations while it is at war. Normally, in wartime, governments massively increase taxes and expand their reach. …The goal, Zablotskyy says, is to ensure that these economic reforms, which were adopted as temporary measures, remain in place after the war. …Everyone agrees that there is an urgent need for reform, especially as so many of the regulations in force in Ukraine date back to the Soviet era of the 1970s. …it is not a Marshall Plan that will help Ukraine, but only market-economy reforms.

Amen. The Marshall Plan to aid Europe after World War II. was largely ineffective. Or even harmful. We should not repeat that mistake in Ukraine.

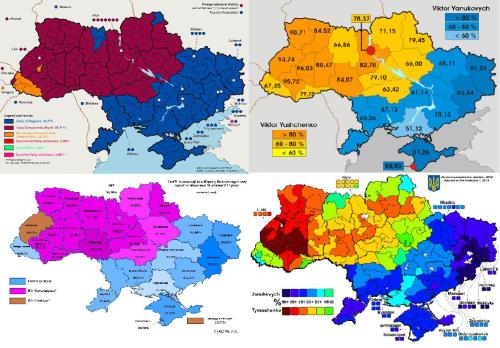

As shown by Germany’s post-war economic miracle, free markets are the answer. The difference between West Germany and East Germany tells us everything we need to know.