During the debate about the Trump tax plan, proponents made three main arguments in favor of reducing the federal corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent.

- A lower rate would be good for workers, consumers, and shareholders.

- A lower rate would boost American competitiveness.

- A lower rate would produce some revenue feedback for the IRS.

The last item involves the “Laffer Curve,” which is a graphical representation of the non-linear relationship between tax rates and tax revenue.

Put in simple terms, entrepreneurs, investors, and business owners have more incentive to earn money when tax rates are modest.

High tax rates, by contrast, discourage productive behavior while also giving people a bigger incentive to find loopholes and other ways of avoiding tax.

High tax rates, by contrast, discourage productive behavior while also giving people a bigger incentive to find loopholes and other ways of avoiding tax.

This does not mean that lower tax rates produce more revenue, though that sometimes happens.

The main takeaway is the most modest observation that lower tax rates will lead to more taxable income, which means some revenue feedback.

In other words, tax cuts don’t lose as much revenue as predicted by simplistic models (and tax increases don’t generate as much revenue as predicted).

I’ve shared many, many real–world examples of this phenomenon.

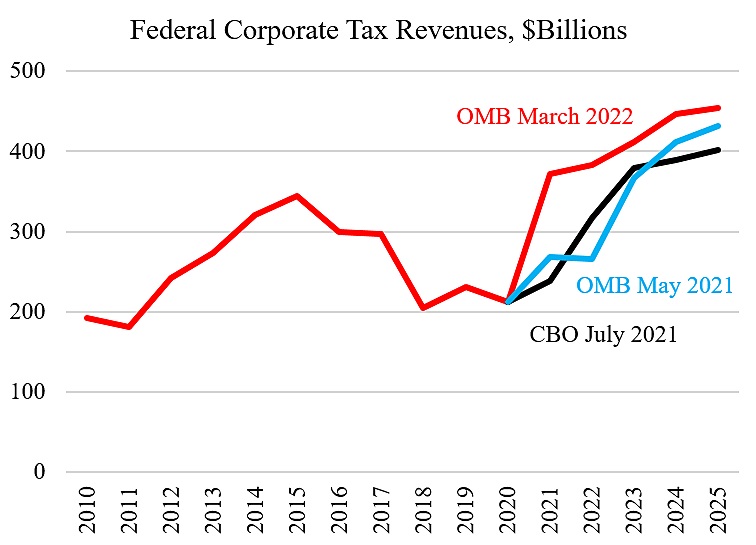

And here’s another. Look at how corporate tax revenues in the United States are increasing at a faster rate than projected.

The chart comes from Chris Edwards, and he helpfully explains what has happened.

The revenue surge came as a surprise to government economists. The chart…compares the new Office of Management and Budget March 2022 baseline projections to prior baseline projections from the OMB in May 2021 and the Congressional Budget Office in July 2021.

…congressional estimators figured that the government would lose an average $76 billion a year the first four years… Corporate tax revenues were down from 2018 to 2020, but then soared in 2021. Revenues in 2021 of $372 billion (with a 21 percent tax rate) are 25 percent higher than revenues in 2017 of $297 billion (with a 35 percent tax rate). …we’re learning that a lower corporate tax rate is consistent with strong corporate tax revenues. …lower rates…broaden bases automatically through reduced tax avoidance and higher economic activity. Other nations have learned the same lesson. Keeping the corporate tax rate low is a winner for businesses and workers, but it can also be a winner for government budgets.

The Wall Street Journal has a new editorial on this topic. Here are some relevant excerpts.

…the 2017 tax reform that cut corporate tax rates…has been a winner for the economy and federal tax coffers. …Corporate revenue was supposed to fall to historic lows

as a share of the economy. Big business supposedly got a windfall and government was robbed. It hasn’t turned out that way. …the big news now is that more corporate tax revenue is flowing into the Treasury at record levels even with the lower rate. …In June 2017, before tax reform passed, CBO predicted corporate tax revenue of $383 billion in fiscal 2021. But in April 2018, after reform passed, CBO lowered its estimate to $327 billion.

So what happened in the real world?

Actual corporate income tax revenue in 2021 was $372 billion—nearly as much at a 21% rate as CBO expected at the 35% rate that was among the highest in the world.

Fiscal 2022 is turning out to be even better for the Treasury. Corporate tax revenue for the first six months was up 22% from a year earlier to $127 billion. …What accounts for this windfall for Uncle Sam…? …the Occam’s razor policy answer is that corporate tax reform worked as its sponsors predicted: Lowering the rates while broadening the base by eliminating loopholes created incentives for more efficient investment decisions that paid off for shareholders, workers and the government.

Notice, by the way, that corporate tax revenues have increased faster than projected in both the 2017 forecast and the 2021 forecast.

All of which shows that I may have been insufficiently optimistic when I wrote about this issue last year.

P.S. The goal of tax policy (either in general or when looking at business taxation) is not to maximize revenue for politicians, but rather to maximize prosperity for people. Indeed, if better tax policy leads to a lot of revenue feedback, that’s an argument for further reductions in tax rates.

P.P.S. Both the IMF and OECD have research showing that lower corporate tax rates do not necessarily lead to lower corporate tax revenues.

[…] Corporate Taxes and the Laffer Curve […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Corporate Taxes and the Laffer Curve […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Very similar to what I wrote in 2021 and 2022. […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] Mnunchin claimed the entire tax cut would pay for itself, he clearly deserves to be mocked, but it’s worth noting that the lower corporate tax rate from the 2017 reform is very close to being […]

[…] tax rates. And that they won’t lose as much revenue as they fear when they lower tax rates (and we saw that most recently with the 2017 tax […]

[…] tax rates. And that they won’t lose as much revenue as they fear when they lower tax rates (and we saw that most recently with the 2017 tax […]

[…] tax rates. And that they won’t lose as much revenue as they fear when they lower tax rates (and we saw that most recently with the 2017 tax […]

[…] rates. And that they won’t lose as much revenue as they fear when they lower tax rates (and we saw that most recently with the 2017 tax […]

[…] cut, regardless of duration, the goal should be to get the most bang for the buck. And there’s plenty of evidence (from the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom) that lowering […]

[…] cut, regardless of duration, the goal should be to get the most bang for the buck. And there’s plenty of evidence (from the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom) that lowering […]

[…] cut, regardless of duration, the goal should be to get the most bang for the buck. And there’s plenty of evidence (from the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom) that lowering […]

[…] cut, regardless of duration, the goal should be to get the most bang for the buck. And there’s plenty of evidence (from the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom) that lowering […]

[…] regardless of duration, the goal should be to get the most bang for the buck. And there’s plenty of evidence (from the United States, Australia, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom) that lowering […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] So Biden’s plan is probably to raise taxes on the wealthy in order to reduce the budget deficit, and thus reduce the need for the Fed to cover the deficit with newly created money. One flaw in that plan is that, as Arthur Laffer illustrated with his famous “curve,” higher tax rates do not necessarily mean higher tax revenue, as economist Daniel Mitchell explains. […]

[…] Corporate Taxes and the Laffer Curve […]

Reblogged this on Utopia, you are standing in it!.

[…] Corporate Taxes and the Laffer Curve […]

Repeal 16th Amendment; implement the FairTax; implement a constitutional cap on federal spending.