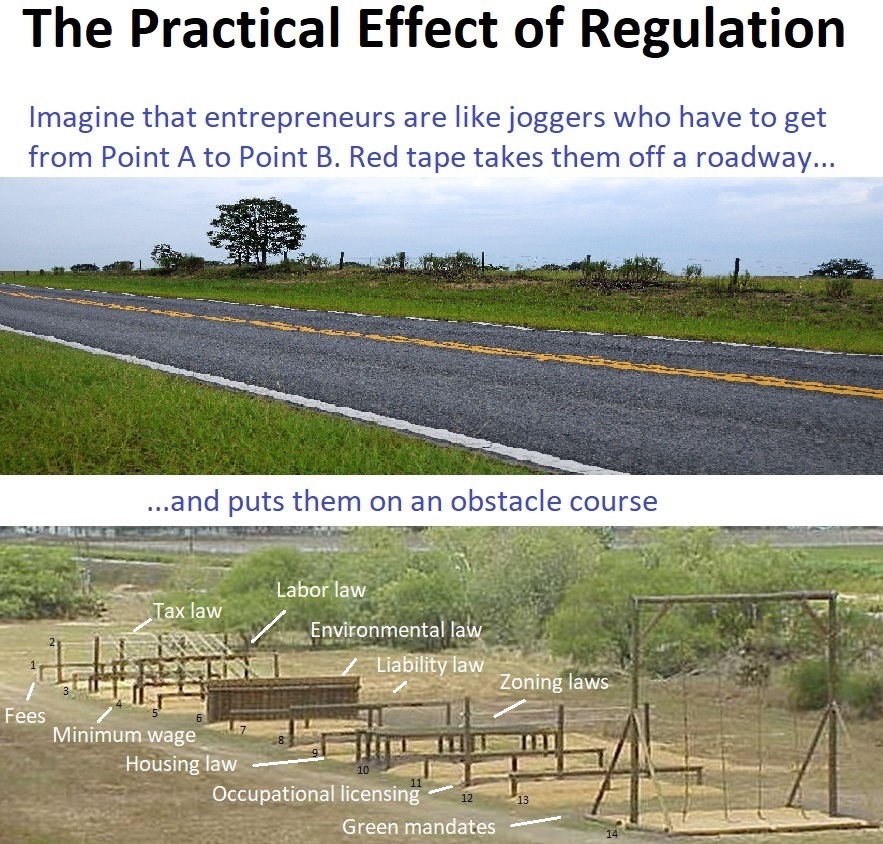

Too much government can be hazardous to your health.

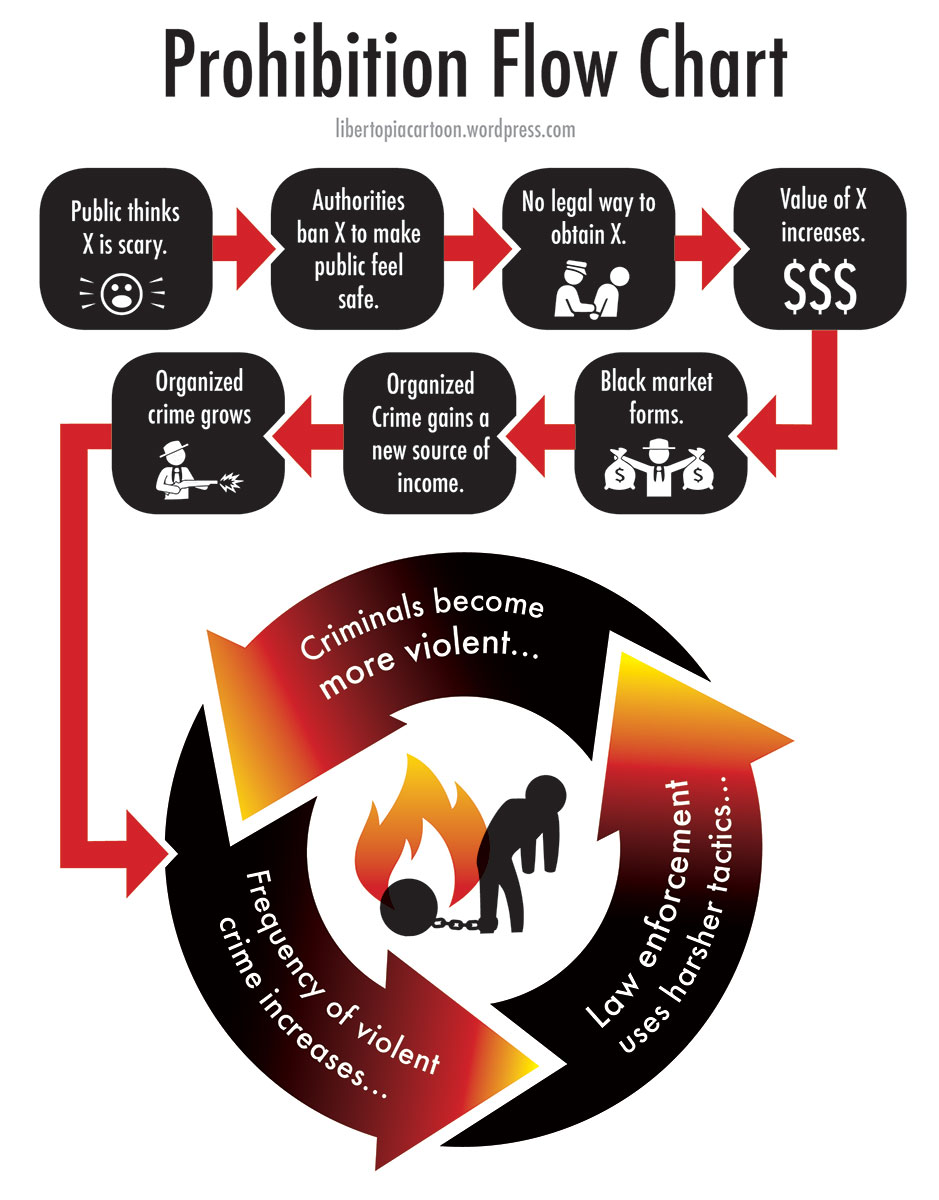

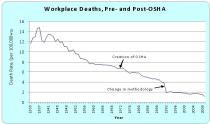

Instead, this is a column about the wonky issue of cost-benefit analysis. Specifically, we’re going to look at whether some regulations can be sufficiently onerous that the resulting economic damage actually produces needless death. This insight can even apply to regulations that are designed to save lives!

It’s quite common, when I first suggest this hypothesis, for people to think I’m nuts. But they begin to see the light when I share this example from an article I wrote 25 years ago for the Journal of Regulation and Social Cost.

People in wealthier nations, on average, live longer and better lives than residents of poorer nations. …government policy makers should consider the adverse effects on health and mortality of economic policies that impose costs on the productive sector of the economy.  …it is quite possible that regulations designed to reduced mortality and morbidity, if they impose sufficiently high costs on the economy, actually can result in premature deaths and a less healthy population. Banning the use of motor vehicles, for instance, would save…lives lost annually in traffic accidents as well as preventing whatever number of premature deaths can be attributed to auto emissions. …It would be absurd, however, to…support the elimination of motor vehicles… The higher living standards made possible by fast and efficient transportation clearly must result in reduced mortality…rates over time for the general population.

…it is quite possible that regulations designed to reduced mortality and morbidity, if they impose sufficiently high costs on the economy, actually can result in premature deaths and a less healthy population. Banning the use of motor vehicles, for instance, would save…lives lost annually in traffic accidents as well as preventing whatever number of premature deaths can be attributed to auto emissions. …It would be absurd, however, to…support the elimination of motor vehicles… The higher living standards made possible by fast and efficient transportation clearly must result in reduced mortality…rates over time for the general population.

I don’t know if they accept that society would be so much poorer that – on net – more people would die. But they definitely grasp that there’s a tradeoff.

And that’s a big victory. After all, people are much more likely to accept cost-benefit analysis when they understand that a decision can have both good and bad consequences.

I wrote about this topic back in 2012 because supporters of President Obama basically accused Mitt Romney of contributing to the death of a woman who lost her health insurance. So I looked at the academic data on the relationship between economic prosperity and lifespans to measure Obama’s body count.

Looking over much of this research, it appears that $14 million is a reasonable middle-ground estimate of how much foregone income is associated with a needless death. Now let’s do some simple math to get an estimate of the total number of preventable deaths caused by the economy’s sub-par performance during Obama’s reign. …divide $836.6 billion (our earlier estimate of foregone growth) by $14 million and we get an estimate that Obama’s policies have caused 59,757 deaths.

In that column, I warned that my back-of-the-envelope calculations were not very unreliable, and I also pointed out that it would be wrong to hold Obama personally accountable for any premature deaths.

I simply wanted people to understand that a weak economy has serious consequences (I also thought that Obama’s supporters were making a very dodgy attack on Romney, particularly since there were so many other reasons to criticize the GOP candidate).

But I’m beginning to digress. The purpose of today’s column is to further explain why we should be concerned about the economic damage of excessive government. But not just because of lost income and reduced prosperity. We also need to recognize that a weaker economy translates into needless deaths.

So let’s look at some additional research.

A study prepared for the Environmental Protection Agency provides a dispassionate analysis of this form of cost-benefit analysis. The report starts with a couple of specific examples.

The essence of risk-risk analysis, as it will be referred to here, is the assertion that regulations seeking risk-reduction benefits may also unintentionally increase risks, and by enough in some cases to outweigh the intended benefits. …One such situation currently of concern is the possibility that parents with young children might elect the more risky option of driving a long distance instead of the less risky alternative of flying if the latter alternative is rendered much more expensive by a requirement to purchase a seat on the aircraft for the child instead of sharing a seat with the parent. Similarly, if regulations governing small drinking system quality are sufficiently costly, individuals might elect to use private wells, which could pose even more risks to their health than the public water supply in the absence of the costly rules.

It then puts forth the sensible hypothesis about the economy-wide implications of onerous red tape.

A slightly different version of risk-risk analysis is predicated on the observation that people’s wealth and health status, as measured by mortality, morbidity, and other metrics, are positively correlated. Hence, those who bear a regulation’s compliance costs may also suffer a decline in their health status, and if the costs are large enough, these increased risks might be greater than the direct risk-reduction benefits of the regulation. Advocates of risk-risk analysis emphasize its use as an important commonsense screen… It does seem eminently reasonable not to promulgate costly rules that actually increase risks rather than decrease them.

The study looks at some of the past academic literature.

Lutter and Morrall (1994) attribute to Aaron Wildavsky, see for example Wildavsky (1980), the general proposition that government programs tend to reduce economic growth, thereby interfering with the primary mechanism by which human health has improved over time. According to Lutter and Morrall, the first to apply this principle quantitatively was Keeney (1990), who calculated that an additional death occurs for roughly each $3.14 million to $7.25 million of income lost (1980 dollars). OMB on several occasions has brought health-health analysis to bear both in its review of OSHA regulations related to worker safety, and in examining regulations of other agencies, such as EPA and FDA. For example, using a finding that $7.5 million of costs induces one additional statistical death, OMB argued that although OSHA’s proposed permissible exposure limits for a large number of workplace air contaminants would offer the benefit of preventing 8 to 13 deaths per year, the regulatory costs of $163 million per year would indirectly cause some 22 deaths annually. On that basis, OMB suspended its review of the proposed regulation and OSHA agreed to study the issue further….researchers continue to further refine this estimated relationship between income and mortality risk. For example, Viscusi (1994) reports various estimates of the lost income that induces an additional statistical death ranging from $1.9 million to $33.2 million, and indicates that his own research (in press at the time) places this number at about $30 million to $70 million.

Keep in mind that the Environmental Protection Agency is not a hotbed of free market radicals. So it’s noteworthy that at least some people at that bureaucracy realize that there should be some cost-benefit constraints on regulation.

The Institute of Energy Research also explored the issue.

…in practice we all make decisions that increase the risk of death, and in that sense, we trade off our own longevity for other goals. In this context, economists can estimate the implied value of a human life, judged by the choices of the individuals themselves. One surprising implication of this approach is that costly government regulations not only reduce Americans’ standard of living, but they also indirectly lead to more deaths. In a modern economy, wealth is health, and so an inefficient regulation doesn’t merely reduce GDP—it also reduces average lifespans. …By analyzing consumer behavior, economists can come up with rough estimates of the implied “value of a statistical life” (VSL) that this behavior exhibits.

Here’s an example.

…suppose a very stringent rule on the emission of soot from smokestacks theoretically would reduce deaths by 2,000 lives, but at an aggregate cost to the economy of $80 billion in forfeited GDP. With these numbers, even on its own terms, such a regulation would save lives at a price of $40 million per life. This is much more than typical Americans spend with their own money to reduce risks and prolong their lifespans, and thus it indicates that the proposed regulation is inefficient because it implicitly forces Americans to “spend” much more on reducing a particular risk, rather than on other goods and services that they value more.

And here’s the key takeaway.

…there is a well-established causal connection between wealth and health. Costly federal regulations make Americans poorer and thus indirectly lead to more deaths, because poorer people are less able to take advantage of private methods of prolonging their lives. If regulations are particularly inefficient, this indirect effect might overwhelm the direct benefit of the regulation, meaning that it not only makes Americans poorer, but actually kills them on net.

Here are some excerpts from a study published by the AEI-Brookings Joint Center for Regulatory Studies.

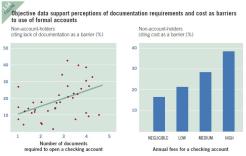

Many forms of regulation have grown dramatically in recent decades—especially in the areas of environment, health, and safety. Moreover, expenditures in those areas are likely to continue to grow faster than the rate of government spending. Yet, the economic impact of regulation receives much less scrutiny than direct, budgeted government spending. We believe that policymakers need to rectify that imbalance. …We should judge regulations by their individual benefits and costs… One study found that a reallocation of mandated expenditures toward those regulations with the highest payoff to society could save as many as 60,000 more lives per year at no additional cost. …the costs of compliance with regulations pose risks. Compliance typically reduces the amount of private resources that people have to spend on a wide range of activities, including health care, children’s education, and automobile safety. When people have fewer resources, they spend less to reduce risks. The resulting increase in risk offsets the direct reduction in risk attributable to a government action. Moreover, if that direct risk reduction is small and the regulation is very ineffective relative to its cost, then total risk could rise instead of fall.

The AEI-Brookings report also looks at some of the existing research.

Dozens of articles in economics and public health journals substantiate the claim that richer people live longer.10 Simple correlations of annual death rates and income suggest that a community whose income rises by about $10 million can expect about one fewer death. …Sunstein argued that courts should find that regulations that raise risks rather than lower them are arbitrary and capricious. … Lutter, Morrall, and Viscusi…estimated that an increase in income of about $15 million in a large U.S. population reduces mortality risk by one statistical death.

The authors look at regulations from the 1980s and 1990s and calculate which ones saved lives and which ones cost lives.

By the way, allow me to interject by pointing out some specific examples of regulations that are on the books and are causing needless deaths.

Now let’s close with a look at a very recent analysis from the Mercatus enter.

…many regulations result in unintended consequences that increase mortality risk in various ways. These adverse repercussions are often the result of regulatory impacts that compete with the intended goal of the regulation, or they are direct behavioral responses to regulation. As examples, fuel efficiency regulations can encourage automobile manufacturers to produce smaller cars that are more dangerous in an accident (Crandall and Graham 1989). Increased airport security measures after 9/11 made air travel more inconvenient, which has led to increases in estimated car accident deaths as individuals substituted driving for flying (Blalock, Kadiyali, and Simon 2007). …Finally, regulatory efforts reduce individual expenditures on health, both because risk reduction achieved through regulation is a substitute for private risk reduction and because the costs incurred by regulations reduce private health-related expenditures. It is this last item that has been the focus of health-health analysis (HHA).

The authors look at potential ways of conducting this type of cost-benefit analysis.

Despite a robust academic literature that spans decades, HHA has not become widely used by policymakers… HHA relies on an estimate of what is known as the cost-per-life-saved cutoff (the “cutoff”), which is a threshold cost-effectiveness level beyond which life-saving regulations will be counterproductive in that they can be expected to induce more fatalities than they prevent. …There are two competing ways of identifying the cutoff, a direct approach based on empirical observation and an indirect approach grounded in economic theory. …The indirect approach, which is our preferred method, relies on a theoretical model of the income-mortality relationship that is calibrated using data on the value of a statistical life (VSL) and the marginal propensity to spend on health (MPSH). …Employing the indirect approach has led to a cost-per-life-saved cutoff value closer to $85 million for the United States. We employ the indirect approach here as well, estimating a cutoff range from $75.4 million to $123.2 million (2015 dollars). A reasonable rule of thumb might be to assume that regulations costing more than $100 million per life saved will be counterproductive in that they can be expected to increase mortality risk on net.

Like the other studies, there’s a look at previous research.

Ralph Keeney developed the first formal model for estimating fatalities induced by income losses, finding that for every $7.25 million (1980 dollars) in costs, one statistical fatality will be induced (Keeney 1990). Chapman and Hariharan’s (1994) study, published in a special issue of the Journal of Risk and Uncertainty devoted to HHA, develops a similar empirical model but controls for initial health status as a means to account for reverse causality (i.e., poor health causing lower income). The study’s authors estimate the cutoff at $12.2 million (1990 dollars). Keeney provided an update of his model in 1997, estimating the cutoff at between $5 million and $14 million (1991 dollars), depending on the distribution of costs.

Including some foreign studies.

Elvik (1999) is a Norwegian study that estimated the cutoff in Norway at between 25 million and 317 million NOK (1995 prices), which translates to US$3.8 million to US$47.5 million (1995 US dollars). Gerdtham and Johannesson (2002) used longitudinal data (tracking individuals for between 10 and 17 years) for a sample of randomly selected Swedes. After controlling for initial health status, they estimated the cutoff at between US$6.8 million and US$9.8 million (1996 US dollars), depending on how costs are distributed. More recently, Ashe et al. (2012) examined fire prevention regulations in Australia. These authors estimate the cutoff at between AU$20 million and AU$50 million (2010 Australian dollars), again depending on how costs are distributed across the population.

The Mercatus study then contemplates the indirect approach, which utilizes the “value of a statistical life” approach, or VSL.

…the empirical evidence from the United States and other countries, as well as the evidence from labor market estimates of the VSL and revealed preference studies, indicate a positive income elasticity of the VSL and a greater income elasticity at lower income levels. This economic mechanism is also consistent with the common conjecture that the mortality effects of regulatory expenditures will be greatest for the poorest members of society. …When a binding government regulation affects risk levels, there will be two effects. First, because health expenditures and job safety levels are substitutes, regulation will decrease the private incentive to invest in health. Second, because the individual bears regulatory costs, there will be decreased investment in health. Whether a regulation reduces risks on balance depends on the sum of three components: the direct effect of the regulation on safety, the indirect effect on risk through a substitution toward safety achieved through regulation and away from personal health expenditures, and the indirect effect on risk as personal health expenditures fall from reduced income as a result of compliance with regulations.

And the authors come up with a range.

According to our estimates, the cost-per-life-saved cutoff is in the range of $75.4 million to $123.2 million (2015 dollars). Any regulation with a cost-per-life-saved that exceeds this range can be expected to increase mortality risk on net. There is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding a number of factors that produce this estimate, however, including the fraction of income spent on risk reduction, the income elasticity of risk-reducing expenditures, and the VSL.

I don’t have the competence to judge which approach is best. The part of me that is worried about excessive red tape hopes the direct approach is more accurate since a lower “cutoff” means we can argue that a greater share of regulations fail to meet the threshold.

On the other hand, the part of me that is resigned to ever-expanding amounts of red tape hopes the indirect approach generates more accurate numbers since a higher “cutoff” means that the net cost of regulation is not as onerous.

Regardless, my only point is that there should be some form of cost-benefit analysis before bureaucrats churn out new rules, and the impact of red tape on overall economic performance should be part of the equation.

P.S. Speaking of economic impact, a study from the European Central Bank had some very sobering data.

Read Full Post »

For instance, a nationwide, 5-miles-per-hour speed limit definitely would reduce traffic fatalities, but lawmakers fortunately don’t impose that kind of rule because it would be absurdly costly.

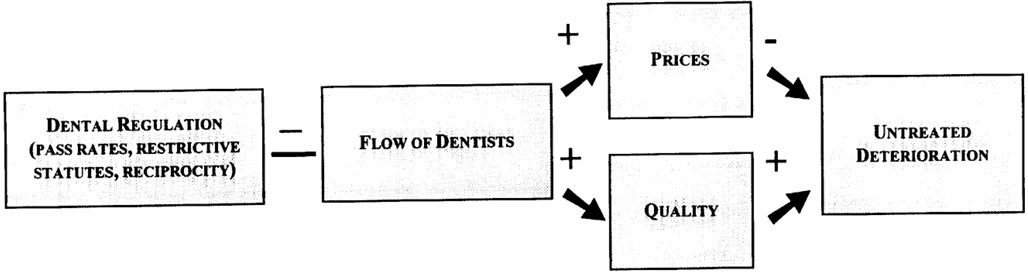

For instance, a nationwide, 5-miles-per-hour speed limit definitely would reduce traffic fatalities, but lawmakers fortunately don’t impose that kind of rule because it would be absurdly costly.We also show that stricter regulation raises prices, but has no effect on untreated deterioration. …more stringent regulation does not appear to affect some indirect measures of service quality, such as lower malpractice premiums or fewer patient complaints. …Our multivariate estimates show that increased licensing restrictiveness did not improve dental health, but it did raise the prices of basic dental services. Further, using several tests for the robustness of our estimates, we found that the states with more restrictive standards provided no significantly greater benefits in terms of lower cost of untreated dental disease. Our estimates…show that more regulated states have somewhat higher dental prices. …Consequently, moving toward more restrictive policies that limit customer access to these services could reduce the welfare of consumers. …To the extent that states are considering a reduction in the pass rate on dental exams or making it more difficult for out of state practitioners to enter, our analysis suggests that there would be no gains to consumers in terms of overall dental health.