Although it doesn’t get nearly as much attention as it warrants, one of the greatest threats to liberty and prosperity is the potential curtailment and elimination of cash.

As I’ve previously noted, there are two reasons why statists don’t like cash and instead would prefer all of us to use digital money (under their rules, of course, not something outside their control like bitcoin).

First, tax collectors can’t easily monitor all cash transactions, so they want a system that would allow them to track and tax every possible penny of our income and purchases.

Second, Keynesian central planners would like to force us to spend more money by imposing negative interest rates (i.e., taxes) on our savings, but that can’t be done if people can hold cash.

To provide some background, a report in the Wall Street Journal looks at both government incentives to get rid of high-value bills and to abolish currency altogether.

Some economists and bankers are demanding a ban on large denomination bills as one way to fight the organized criminals and terrorists who mainly use these notes. But the desire to ditch big bills is also being fueled from unexpected quarter: central bank’s use of negative interest rates. …if a central bank drives interest rates into negative territory, it’ll struggle to manage with physical cash. When a bank balance starts being eaten away by a sub-zero interest rate, cash starts to look inviting. That’s a particular problem for an economy that issues high-denomination banknotes like the eurozone, because it’s easier for a citizen to withdraw and hoard any money they have got in the bank.

Now let’s take a closer look at what folks on the left are saying to the public. In general, they don’t talk about taxing our savings with government-imposed negative interest rates. Instead, they make it seem like their goal is to fight crime.

Larry Summers, a former Obama Administration official, writes in the Washington Post that this is the reason governments should agree on a global pact to eliminate high-denomination notes.

…analysis is totally convincing on the linkage between high denomination notes and crime. …technology is obviating whatever need there may ever have been for high denomination notes in legal commerce. …The €500 is almost six times as valuable as the $100. Some actors in Europe, notably the European Commission, have shown sympathy for the idea and European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi has shown interest as well. If Europe moved, pressure could likely be brought on others, notably Switzerland. …Even better than unilateral measures in Europe would be a global agreement to stop issuing notes worth more than say $50 or $100. Such an agreement would be as significant as anything else the G7 or G20 has done in years. …a global agreement to stop issuing high denomination notes would also show that the global financial groupings can stand up against “big money” and for the interests of ordinary citizens.

Summers cites a working paper by Peter Sands of the Kennedy School, so let’s look at that argument for why governments should get rid of all large-denomination currencies.

Illegal money flows pose a massive challenge to all societies, rich and poor. Tax evasion undercuts the financing of public services and distorts the economy. Financial crime fuels and facilitates criminal activities from drug trafficking and human smuggling to theft and fraud. Corruption corrodes public institutions and warps decision-making. Terrorist finance sustains organisations that spread death and fear. The scale of such illicit money flows is staggering. …Our proposal is to eliminate high denomination, high value currency notes, such as the €500 note, the $100 bill, the CHF1,000 note and the £50 note. …Without being able to use high denomination notes, those engaged in illicit activities – the “bad guys” of our title – would face higher costs and greater risks of detection. Eliminating high denomination notes would disrupt their “business models”.

Are these compelling arguments? Should law-abiding citizens be forced to give up cash in hopes of making life harder for crooks?  In other words, should we trade liberty for security?

In other words, should we trade liberty for security?

From a moral and philosophical perspective, the answer is no. Our Founders would be rolling in their graves at the mere thought.

But let’s address this issue solely from a practical, utilitarian perspective.

The first thing to understand is that the bad guys won’t really be impacted. The head the The American Anti-Corruption Institute, L. Burke Files, explains to the Financial Times why restricting cash is pointless and misguided.

Peter Sands…has claimed that removal of high-denomination bank notes will deter crime. This is nonsense. After more than 25 years of investigating fraudsters and now corrupt persons in more than 90 countries, I can tell you that only in the extreme minority of cases was cash ever used — even in corruption cases. A vast majority of the funds moved involved bank wires, or the purchase and sale of valuable items such as art, antiquities, vessels or jewellery. …Removal of high denomination bank notes is a fruitless gesture akin to curing the common cold by forbidding use of the term “cold”.

In other words, our statist friends are being disingenuous. They’re trying to exploit the populace’s desire for crime fighting as a means of achieving a policy that actually is designed for other purposes.

The good news, is that they still have a long way to go before achieving their goals. Notwithstanding agitation to get rid of “Benjamins” in the United States, that doesn’t appear to be an immediate threat. Additionally, according to SwissInfo, is that the Swiss government has little interest in getting rid of the CHF1,000 note.

The European police agency Europol, EU finance ministers and now the European Central Bank, have recently made noises about pulling the €500 note, which has been described as the “currency of choice” for criminals. …But Switzerland has no plans to follow suit. “The CHF1,000 note remains a useful tool for payment transactions and for storing value,” Swiss National Bank spokesman Walter Meier told swissinfo.ch.

This resistance is good news, and not just because we want to control rapacious government in North America and Europe.

A column for Yahoo mentions the important value of large-denomination dollars and euros in less developed nations.

Cash also has the added benefit of providing emergency reserves for people “with unstable exchange rates, repressive governments, capital controls or a history of banking collapses,” as the Financial Times noted.

Amen. Indeed, this is one of the reasons why I like bitcoin. People need options to protect themselves from the consequences of bad government policy, regardless of where they live.

By the way, if you’ll allow me a slight diversion, Bill Poole of the University of Delaware (and also a Cato Fellow) adds a very important point in a Wall Street Journal column. He warns that a fixation on monetary policy is misguided, not only because we don’t want reckless easy-money policy, but also because we don’t want our attention diverted from the reforms that actually could boost economic performance.

Negative central-bank interest rates will not create growth any more than the Federal Reserve’s near-zero interest rates did in the U.S. And it will divert attention from the structural problems that have plagued growth here, as well as in Europe and Japan, and how these problems can be solved. …Where central banks can help is by identifying the structural impediments to growth and recommending a way forward. …It is terribly important that advocates of limited government understand what is at stake. …calls for a return to near-zero or even negative interest rates…will do little in the short run to boost growth, but it will dig the federal government into a deeper fiscal hole, further damaging long-run prospects. It needs to be repeated: Monetary policy today has little to offer to raise growth in the developed world.

Let’s close by returning to the core issue of whether it is wise to allow government the sweeping powers that would accompany the elimination of physical currency.

Here are excerpts from four superb articles on the topic.

First, writing for The American Thinker, Mike Konrad argues that eliminating cash will empower government and reduce liberty.

Governments will rise to the occasion and soon will be making cash illegal. People will be forced to put their money in banks or the market, thus rescuing the central governments and the central banks that are incestuously intertwined with them. …cash is probably the last arena of personal autonomy left. …It has power that the government cannot control; and that is why it has to go. Of course, governments will not tell us the real reasons. …We will be told it is for our own “good,” however one defines that. …What won’t be reported will be that hacking will shoot up. Bank fraud will skyrocket. …Going cashless may ironically streamline drug smuggling since suitcases of money weigh too much. …The real purpose of a cashless society will be total control: Absolute Total Control. The real victims will be the public who will be forced to put all their wealth in a centralized system backed up by the good faith and credit of their respective governments. Their life savings will be eaten away yearly with negative rates. …The end result will be the loss of all autonomy. This will be the darkest of all tyrannies. From cradle to grave one will not only be tracked in location, but on purchases. Liberty will be non-existent. However, it will be sold to us as expedient simplicity itself, freeing us from crime: Fascism with a friendly face.

Second, the invaluable Allister Heath of the U.K.-based Telegraph warns that the desire for Keynesian monetary policy is creating a slippery slope that eventually will give governments an excuse to try to completely banish cash.

…the fact that interest rates of -0.5pc or so are manageable doesn’t mean that interest rates of -4pc would be. At some point, the cost of holding cash in a bank account would become prohibitive: savers would eventually rediscover the virtues of stuffed mattresses (or buying equities, or housing, or anything with less of a negative rate). The problem is that this will embolden those officials who wish to abolish cash altogether, and switch entirely to electronic and digital money. If savers were forced to keep their money in the bank, the argument goes, then they would be forced to put up with even huge negative rates. …But abolishing cash wouldn’t actually work, and would come with terrible side-effects. For a start, people would begin to treat highly negative interest rates as a form of confiscatory taxation: they would be very angry indeed, especially if rates were significantly more negative than inflation. …Criminals who wished to evade tax or engage in illegal activities would still be able to bypass the system: they would start using foreign currencies, precious metals or other commodities as a means of exchange and store of value… The last thing we now need is harebrained schemes to abolish cash. It wouldn’t work, and the public rightly wouldn’t tolerate it.

The Wall Street Journal has opined on the issue as well.

…we shouldn’t be surprised that politicians and central bankers are now waging a war on cash. That’s right, policy makers in Europe and the U.S. want to make it harder for the hoi polloi to hold actual currency. …the European Central Bank would like to ban €500 notes. …Limits on cash transactions have been spreading in Europe… Italy has made it illegal to pay cash for anything worth more than €1,000 ($1,116), while France cut its limit to €1,000 from €3,000 last year. British merchants accepting more than €15,000 in cash per transaction must first register with the tax authorities. …Germany’s Deputy Finance Minister Michael Meister recently proposed a €5,000 cap on cash transactions. …The enemies of cash claim that only crooks and cranks need large-denomination bills. They want large transactions to be made electronically so government can follow them. Yet…Criminals will find a way, large bills or not. The real reason the war on cash is gearing up now is political: Politicians and central bankers fear that holders of currency could undermine their brave new monetary world of negative interest rates. …Negative rates are a tax on deposits with banks, with the goal of prodding depositors to remove their cash and spend it… But that goal will be undermined if citizens hoard cash. …So, presto, ban cash. …If the benighted peasants won’t spend on their own, well, make it that much harder for them to save money even in their own mattresses. All of which ignores the virtues of cash for law-abiding citizens. Cash allows legitimate transactions to be executed quickly, without either party paying fees to a bank or credit-card processor. Cash also lets millions of low-income people participate in the economy without maintaining a bank account, the costs of which are mounting as post-2008 regulations drop the ax on fee-free retail banking. While there’s always a risk of being mugged on the way to the store, digital transactions are subject to hacking and computer theft. …the reason gray markets exist is because high taxes and regulatory costs drive otherwise honest businesses off the books. Politicians may want to think twice about cracking down on the cash economy in a way that might destroy businesses and add millions to the jobless rolls. …it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the politicians want to bar cash as one more infringement on economic liberty. They may go after the big bills now, but does anyone think they’d stop there? …Beware politicians trying to limit the ways you can conduct private economic business. It never turns out well.

Last, but not least, Glenn Reynolds, a law professor at the University of Tennessee, explores the downsides of banning cash in a column for USA Today.

…we need to restore the $500 and $1000 bills. And the reason is that people like Larry Summers have done a horrible job. …What is a $100 bill worth now, compared to 1969? According to the U.S. Inflation Calculator online, a $100 bill today has the equivalent purchasing power of $15.49 in 1969 dollars. …And although inflation isn’t running very high at the moment, this trend will only continue. If the next few decades are like the last few, paper money in current denominations will become basically useless. …to our ruling class this isn’t a bug, but a feature. Governments want to get rid of cash… But at a time when, almost no matter where you look in the world, the parts of it controlled by the experts and technocrats (like Larry Summers) seem to be doing badly, it seems reasonable to ask: Why give them still more control over the economy? What reason is there to think that they’ll use that control fairly, or even competently? Their track record isn’t very impressive. Cash has a lot of virtues. One of them is that it allows people to engage in voluntary transactions without the knowledge or permission of anyone else. Governments call this suspicious, but the rest of us call it something else: Freedom.

Amen. Glenn nails it.

Banning cash is a scheme concocted by politicians and bureaucrats who already have demonstrated that they are incapable of competently administering the bloated public sector that already exists.

The idea that they should be given added power to extract more of our money and manipulate our spending is absurd. Laughably absurd if you read Mark Steyn.

P.S. I actually wouldn’t mind getting rid of the government’s physical currency, but only if the result was a system that actually enhanced liberty and prosperity. Unfortunately, I don’t expect that to happen in the near future.

Read Full Post »

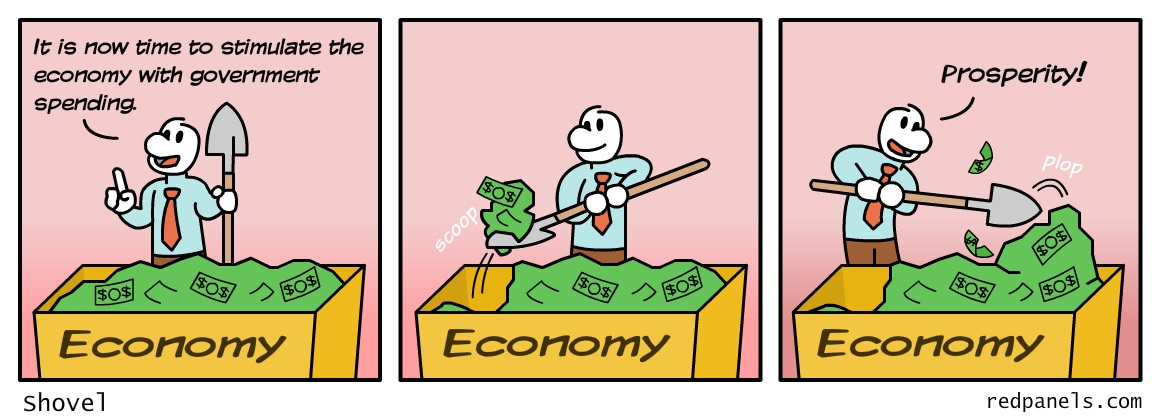

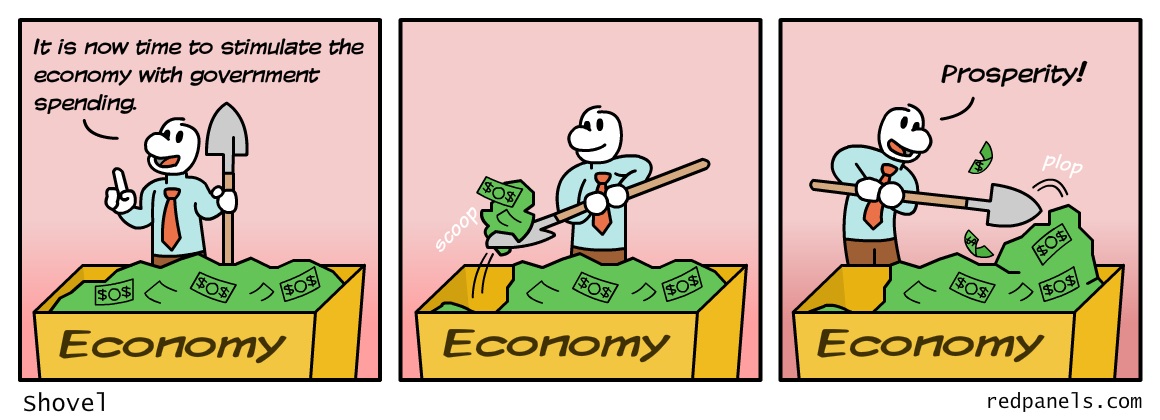

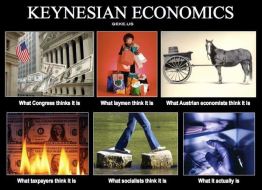

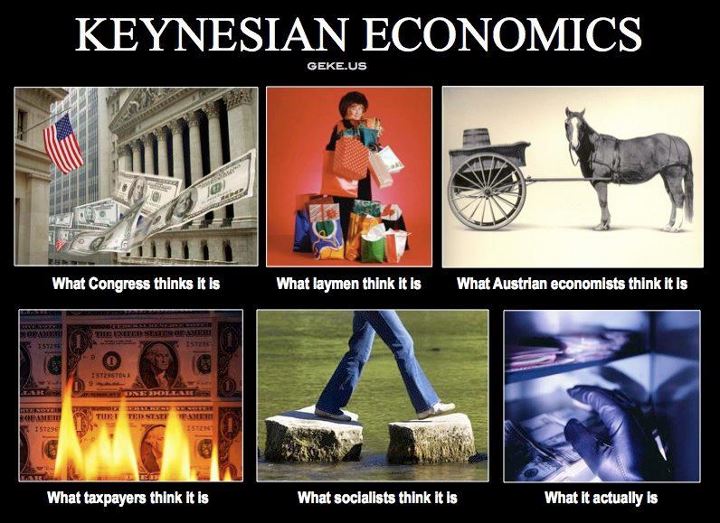

Keynesian economists, by contrast, think it is very important to distinguish between the long run and short run. In the long run, they generally would agree with the previous paragraph.

Keynesian economists, by contrast, think it is very important to distinguish between the long run and short run. In the long run, they generally would agree with the previous paragraph. when Harding slashed spending in the early 1920s).

when Harding slashed spending in the early 1920s).