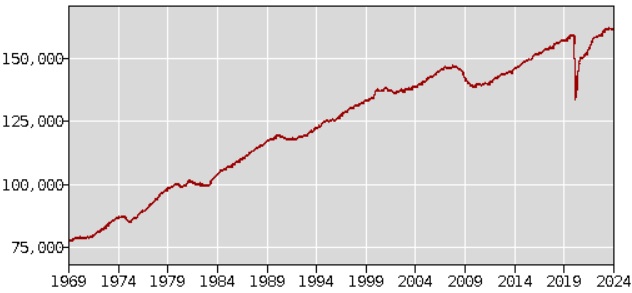

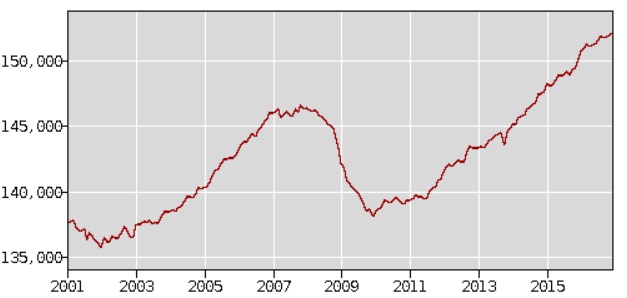

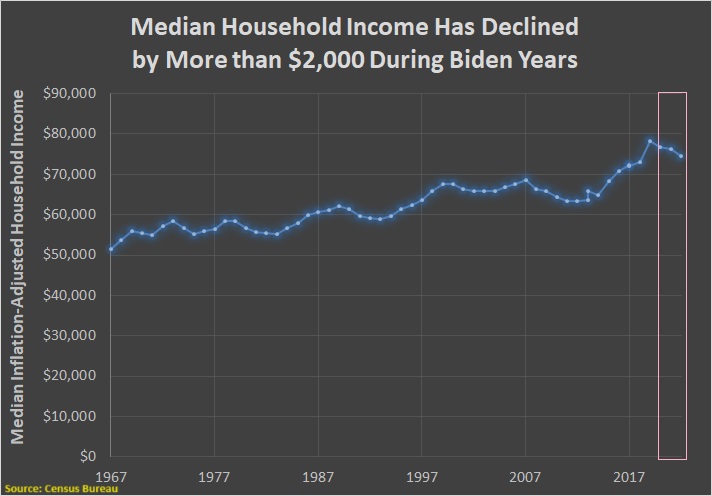

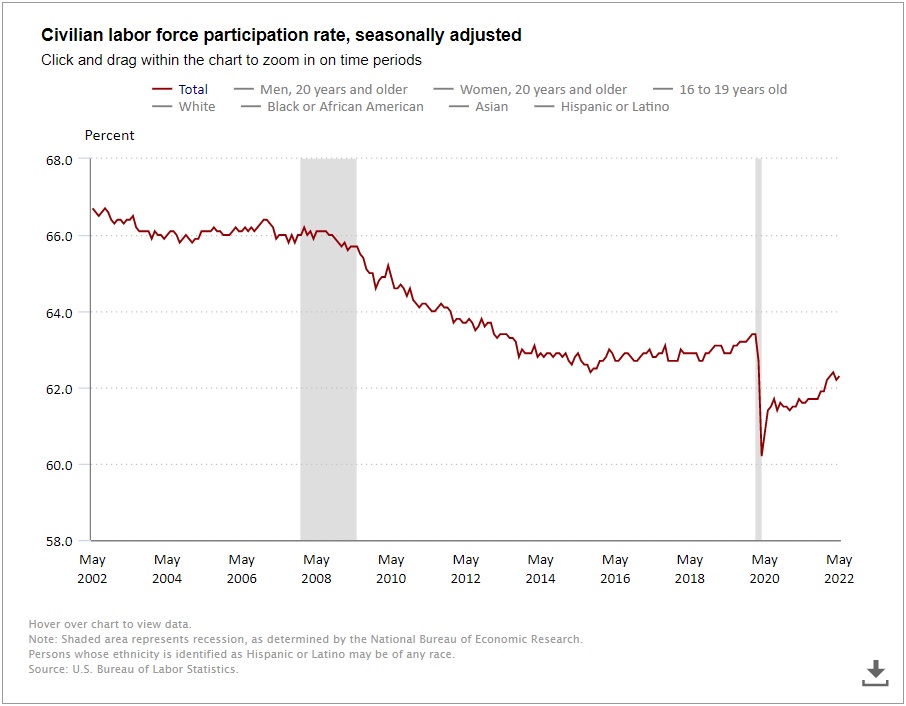

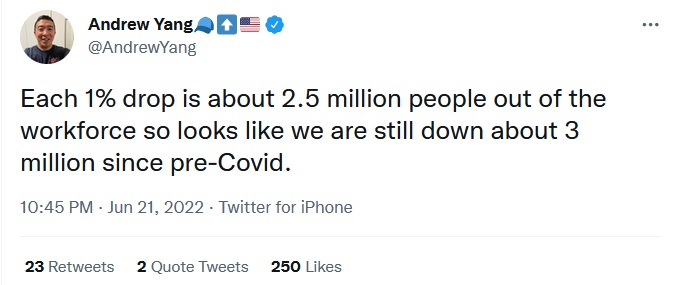

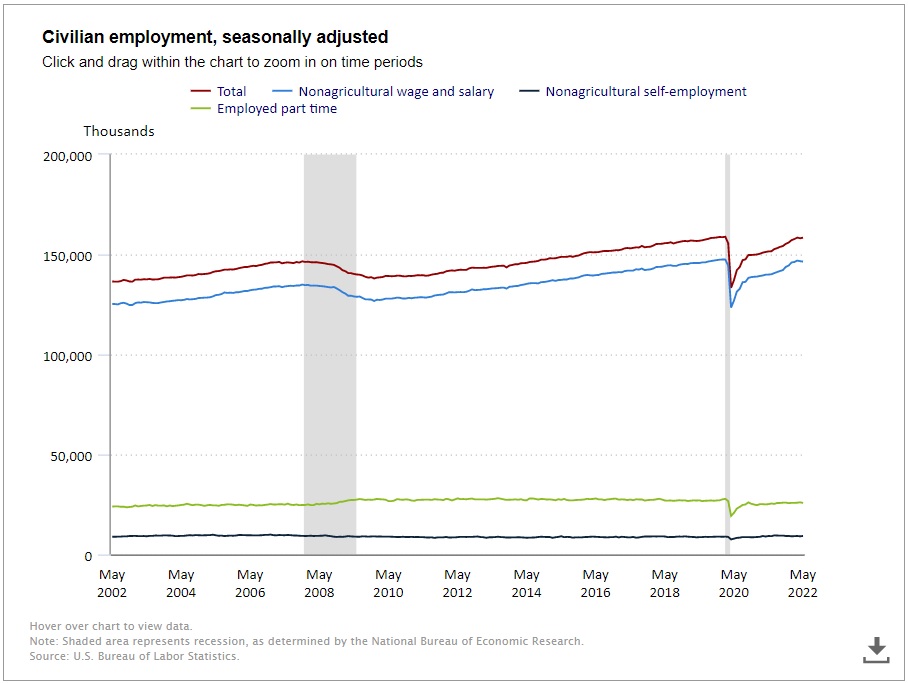

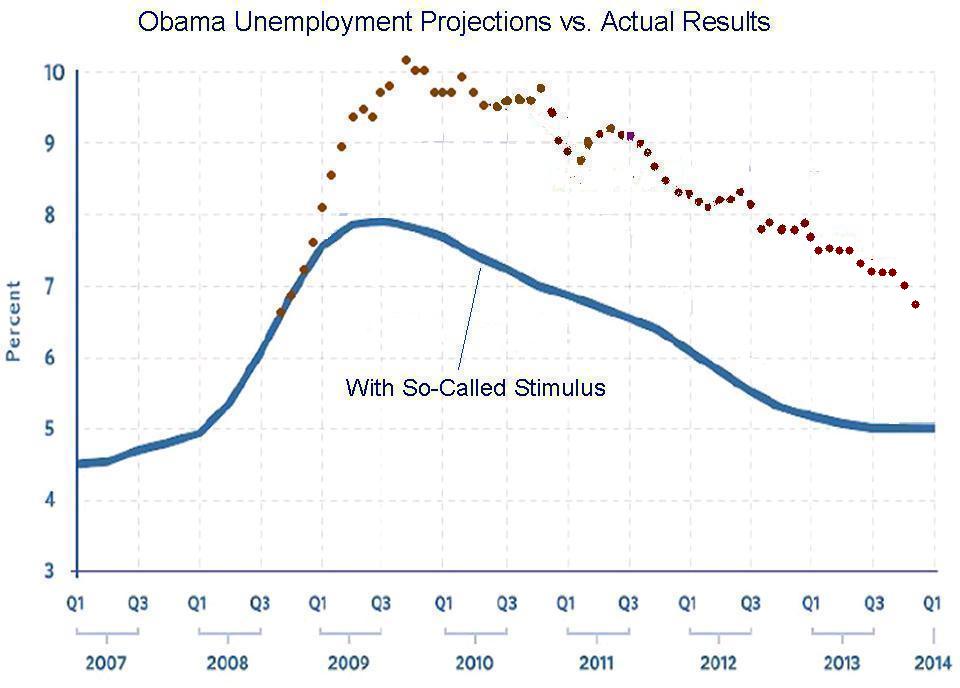

Remember the “jobless recovery” of the Obama years?

Part of the problem was that President Obama kept extending unemployment benefits, which subsidized joblessness, as even  Paul Krugman and Larry Summers had warned.

Paul Krugman and Larry Summers had warned.

The good news was that Congress eventually said no in 2014 (actually one of the three best things to happen that year).

After that happened, the labor market improved.

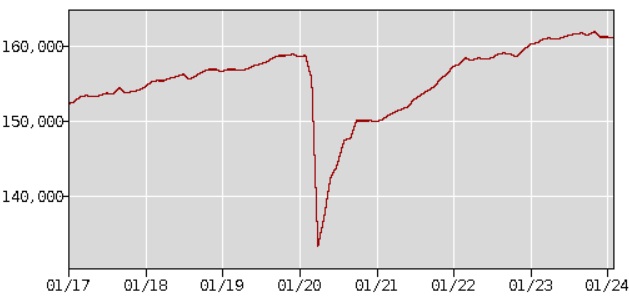

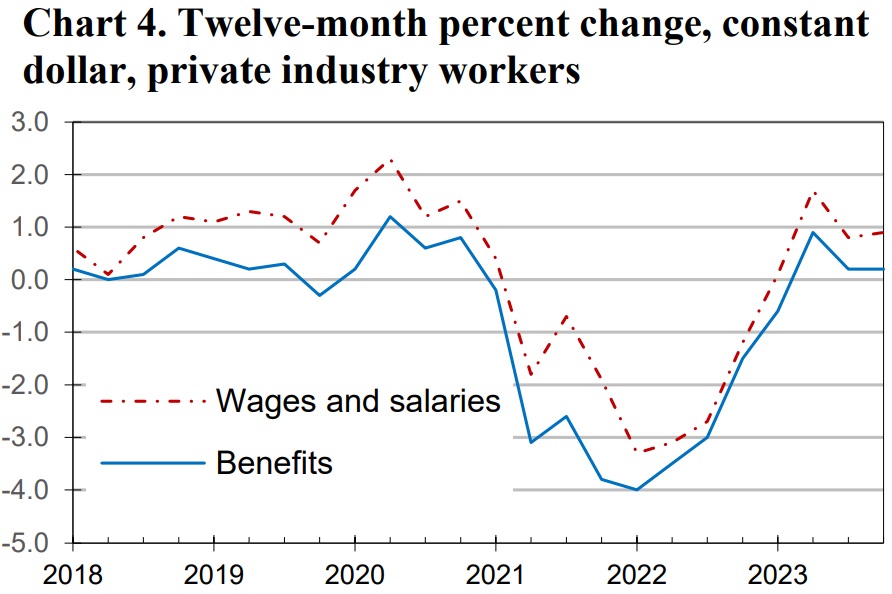

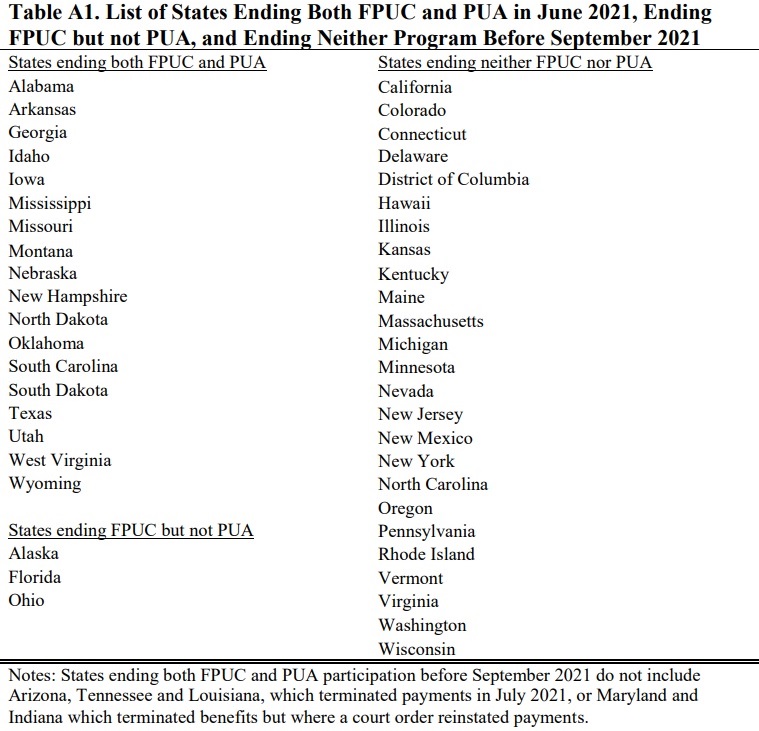

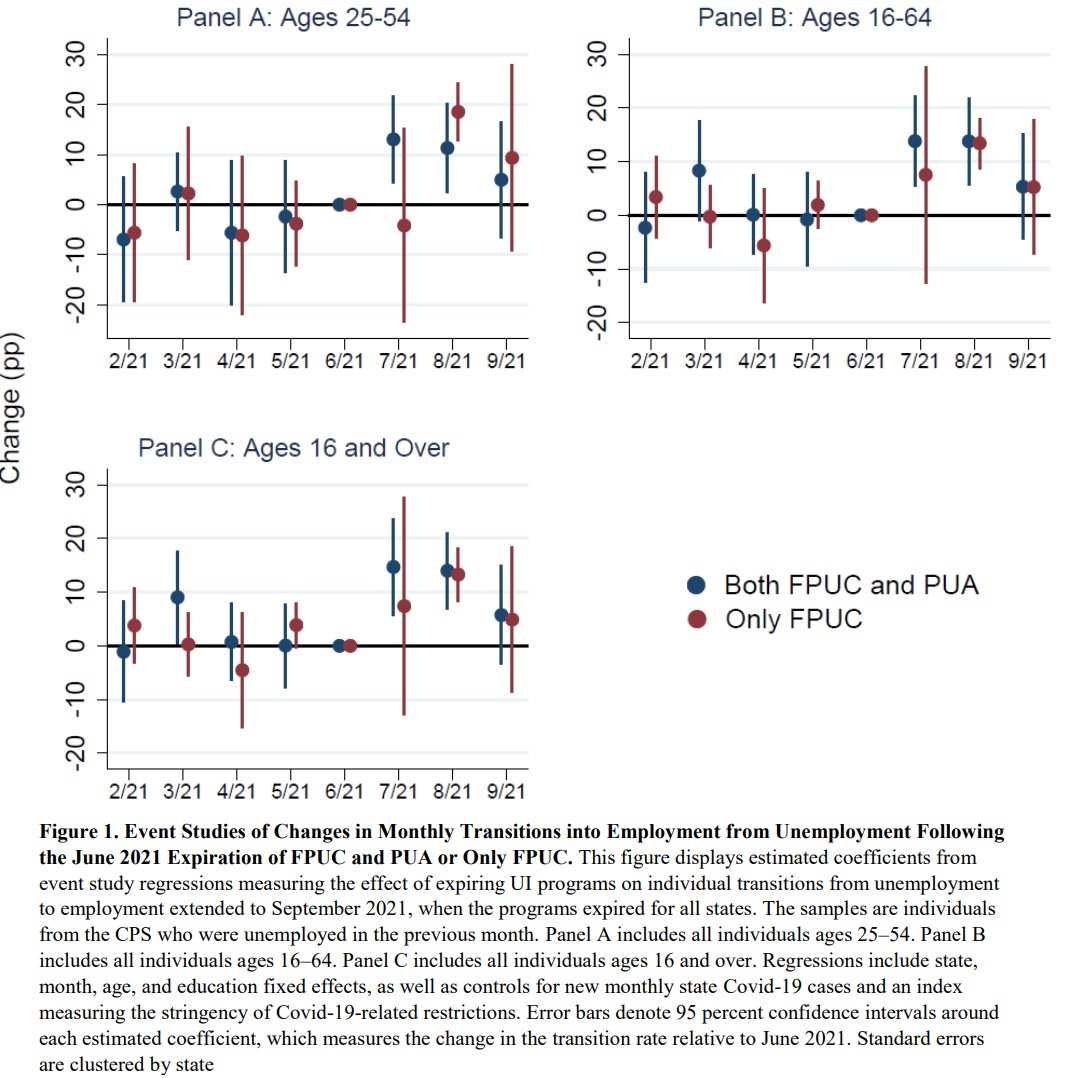

But politicians apparently didn’t learn anything. As part of emergency coronavirus legislation, they turbo-charged unemployment benefits.

The Wall Street Journal‘s editorial from yesterday has a good summary.

Much of the harm from the coronavirus is unavoidable, but it would be nice if politicians didn’t compound the damage by ignoring the laws of economics. The worst blunder so far on that score is the $600 increase in federal jobless benefits…  Why would anyone take a pay cut to go back to work? …Employees say they’ll take the unemployment check for as long as they can make more money by not working. …This does not mean these workers are lazy. Workers are making rational decisions based on the economic incentives the political class has created. …The question now is whether the Trump Administration will learn from its negotiating mistake. Democrats will try to extend the $600 for another few months, and then a few more after that, as they describe anyone who disagrees as heartless.

Why would anyone take a pay cut to go back to work? …Employees say they’ll take the unemployment check for as long as they can make more money by not working. …This does not mean these workers are lazy. Workers are making rational decisions based on the economic incentives the political class has created. …The question now is whether the Trump Administration will learn from its negotiating mistake. Democrats will try to extend the $600 for another few months, and then a few more after that, as they describe anyone who disagrees as heartless.

Tim Kane, in a piece for the Hill, explains why this doesn’t make sense.

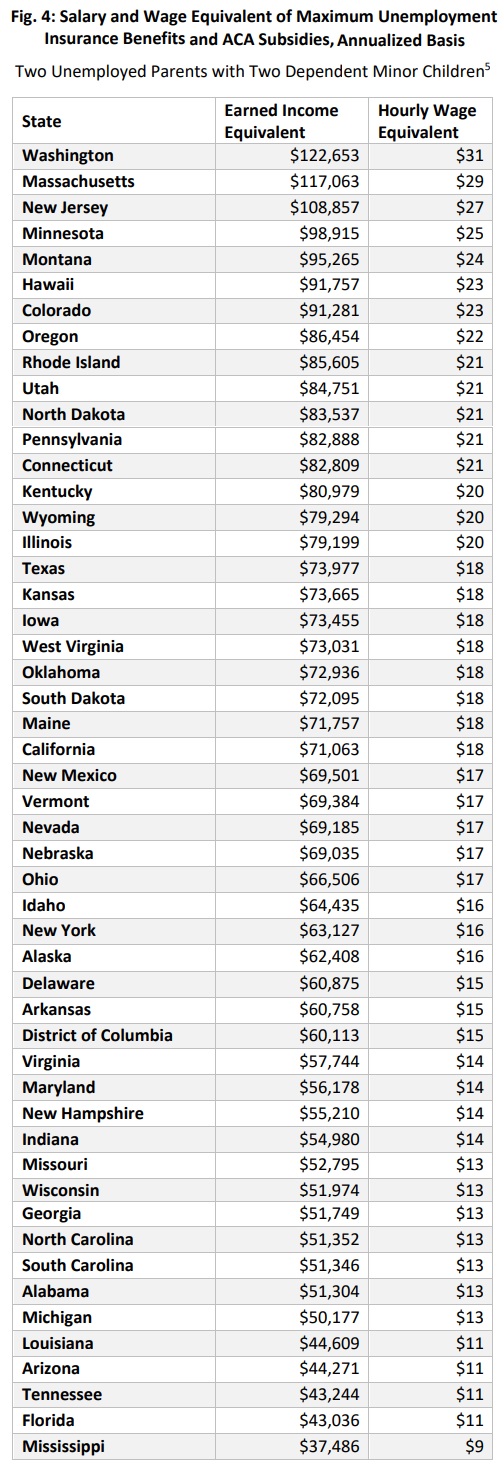

The UI system is a case study in perverse incentives in the best of times, but the four-month “fix” in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES) makes it far worse. …Existing UI provides a government payment to each worker who is involuntarily laid off, in essence paying people not to work. The amount varies slightly according to state-based formulas. But UI checks are generally set to replace 50 percent of the individual’s wages until they find a new job. …Pandemic UI jacks up the replacement rate with a supplemental $600 per unemployed worker for the next four months. That’s roughly an extra $2,400 each month that will go to you only if you are unemployed. …Now that the CARES Act is the law of the land, any American with an annual salary of $62,000 has no financial incentive to work, certainly not until August. …the federal government is going to pay non-working Americans way more than working Americans.

in essence paying people not to work. The amount varies slightly according to state-based formulas. But UI checks are generally set to replace 50 percent of the individual’s wages until they find a new job. …Pandemic UI jacks up the replacement rate with a supplemental $600 per unemployed worker for the next four months. That’s roughly an extra $2,400 each month that will go to you only if you are unemployed. …Now that the CARES Act is the law of the land, any American with an annual salary of $62,000 has no financial incentive to work, certainly not until August. …the federal government is going to pay non-working Americans way more than working Americans.

In a column for Bloomberg, Conor Sen explores the implications.

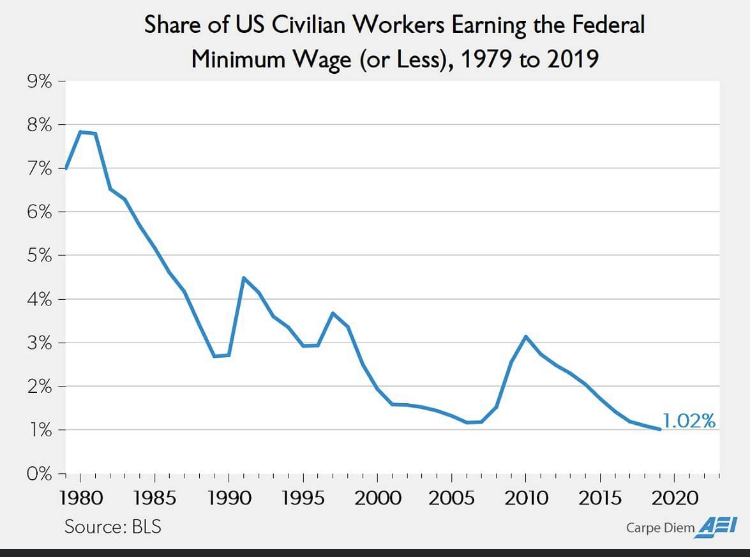

It’s also important to be mindful of how, once the economy is growing again, a $600 weekly benefit can distort the labor market. That works out to the equivalent of $15 an hour for a 40-hour work week,  a level that substantially exceeds the minimum wage in most states. When restaurants are open for business again, they are likely to complain if they can’t hire dishwashers who understand that it’s not worth giving up unemployment benefits. One step to winding down the program might be reducing the benefit over time in response to labor-market conditions and monitoring the impact that’s having on workers accepting jobs.

a level that substantially exceeds the minimum wage in most states. When restaurants are open for business again, they are likely to complain if they can’t hire dishwashers who understand that it’s not worth giving up unemployment benefits. One step to winding down the program might be reducing the benefit over time in response to labor-market conditions and monitoring the impact that’s having on workers accepting jobs.

Sam Hammond, writing for National Review, opines on the potential human cost.

…the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance program…will…add an extra $600 per week to the base benefit (equal to half the state’s regular unemployment benefit) for up to four months. …This $600 per week add-on — equivalent to a $15-per-hour full-time income — means that many workers will soon be eligible to receive more in unemployment compensation than they would make on the job. …It should go without saying that no government in history has ever designed an unemployment-insurance program quite like this — one that virtually anyone can qualify for, and with benefits on par with the median weekly earnings of full-time workers. …a worst-case scenario is easy to imagine…once quarantines begin to lift, a fraction of Pandemic UI recipients will choose to stay on “extended benefits”… Temporary unemployment will become structural, and a jobless recovery will drag out for decades.

means that many workers will soon be eligible to receive more in unemployment compensation than they would make on the job. …It should go without saying that no government in history has ever designed an unemployment-insurance program quite like this — one that virtually anyone can qualify for, and with benefits on par with the median weekly earnings of full-time workers. …a worst-case scenario is easy to imagine…once quarantines begin to lift, a fraction of Pandemic UI recipients will choose to stay on “extended benefits”… Temporary unemployment will become structural, and a jobless recovery will drag out for decades.

Veronique de Rugy of the Mercatus Center cites some of the academic literature.

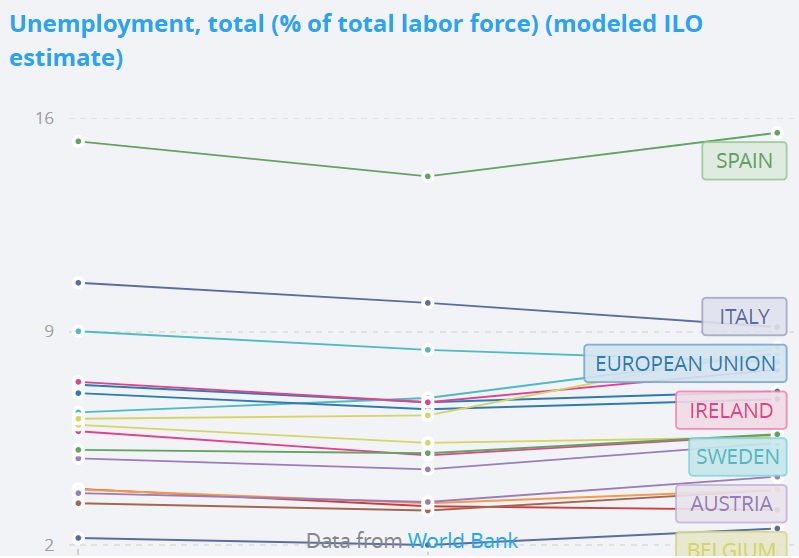

The unintended consequences and moral hazard of UI during normal times and normal recessions are well known. Put briefly, generous UI benefits create an incentive for workers to delay looking for jobs until the expiration of the benefit.  In 2010, Harvard University economist Robert Barro estimated that the Great Recession expansions in UI benefits raised the US unemployment rate by about 2.7 percentage points. …In addition, economists Lawrence F. Katz and Bruce D. Meyer observe that workers receiving unemployment benefits were likely to postpone their job searches until their benefits expired. This finding was confirmed by many other studies, including one by economist Alan Krueger, who wrote in 2008 that “job search increases sharply in the weeks prior to benefit exhaustion.”

In 2010, Harvard University economist Robert Barro estimated that the Great Recession expansions in UI benefits raised the US unemployment rate by about 2.7 percentage points. …In addition, economists Lawrence F. Katz and Bruce D. Meyer observe that workers receiving unemployment benefits were likely to postpone their job searches until their benefits expired. This finding was confirmed by many other studies, including one by economist Alan Krueger, who wrote in 2008 that “job search increases sharply in the weeks prior to benefit exhaustion.”

And she points out that there is a better approach.

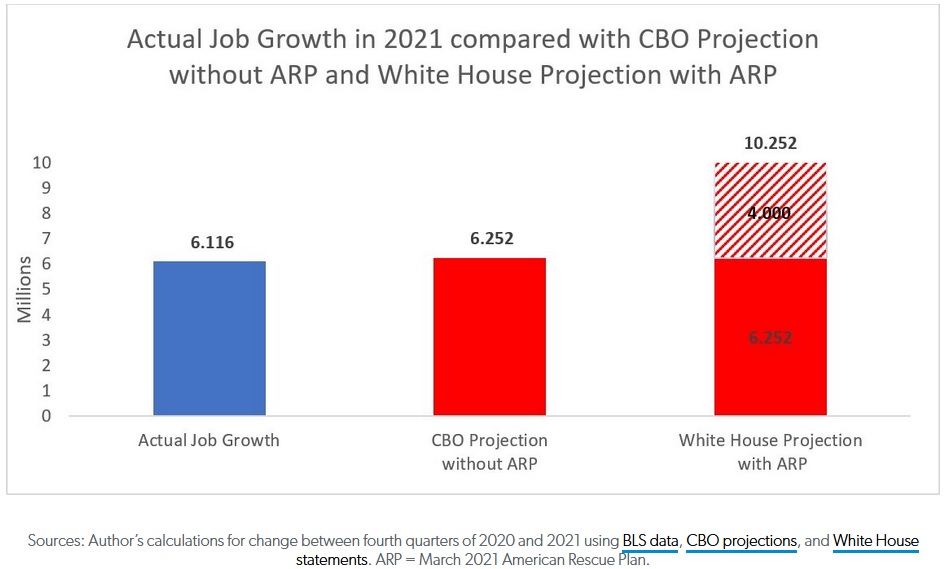

…an old policy proposal that should receive new attention—a proposal that by design encourages people to go back to work as quickly as they can… Personal unemployment insurance savings accounts (PISAs) are designed to maintain a financial incentive to return to work as soon as possible. These accounts are individually owned by workers who, during spells of unemployment, can make orderly withdrawals to partially compensate for the loss to their income but can keep and build the balance during their regular times of employment. …This form of UI is not a mere theoretical proposition. The experience of Chile is worth noting, but other countries such as Austria and Colombia have adopted similar plans.

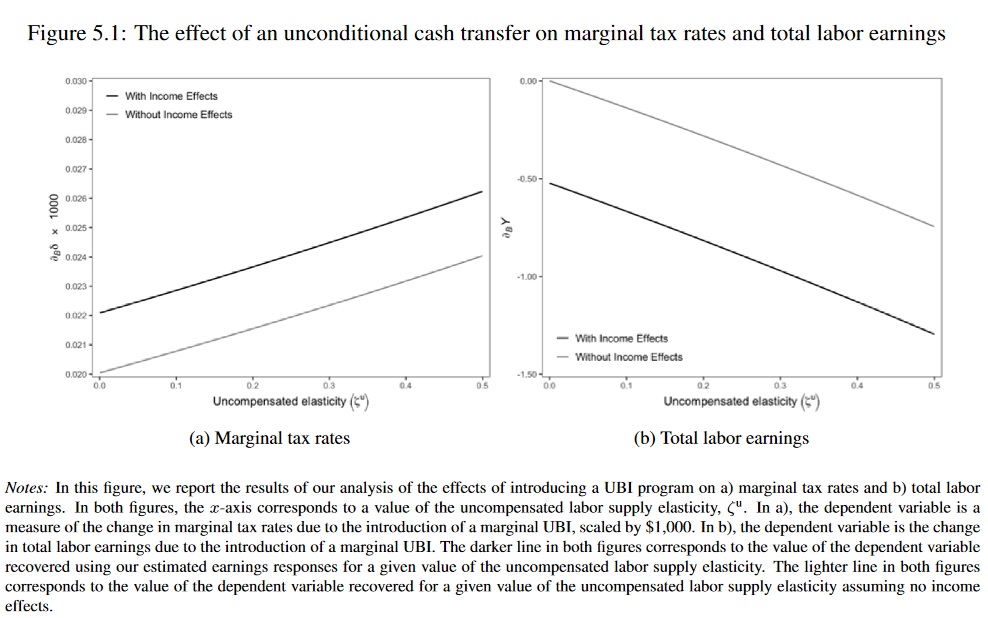

Making a related point, Congressman Justin Amash points out that it would be less harmful to simply give people money rather than giving them money on the condition that they don’t work.

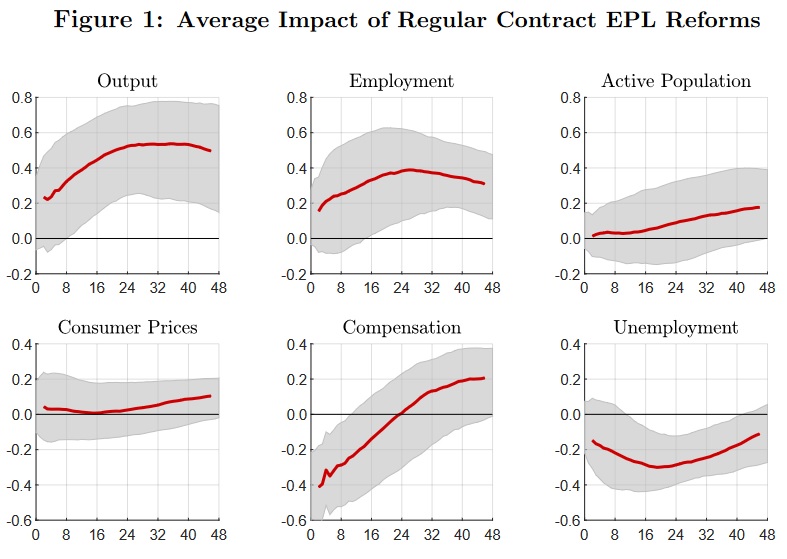

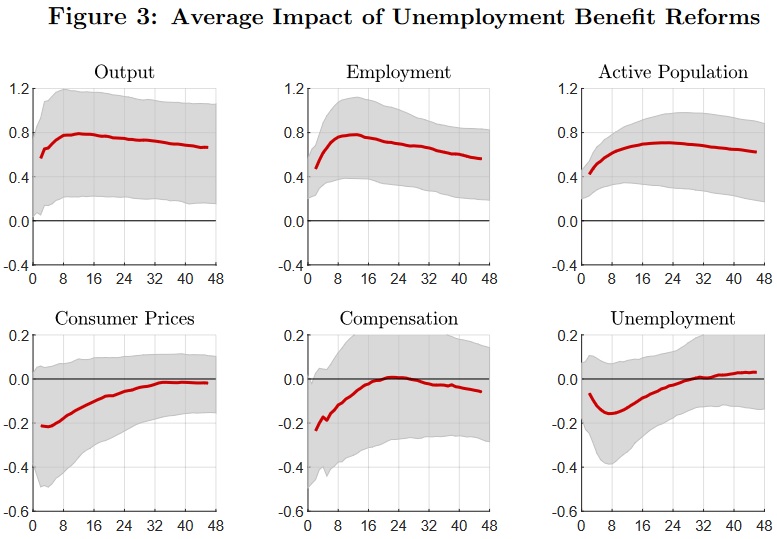

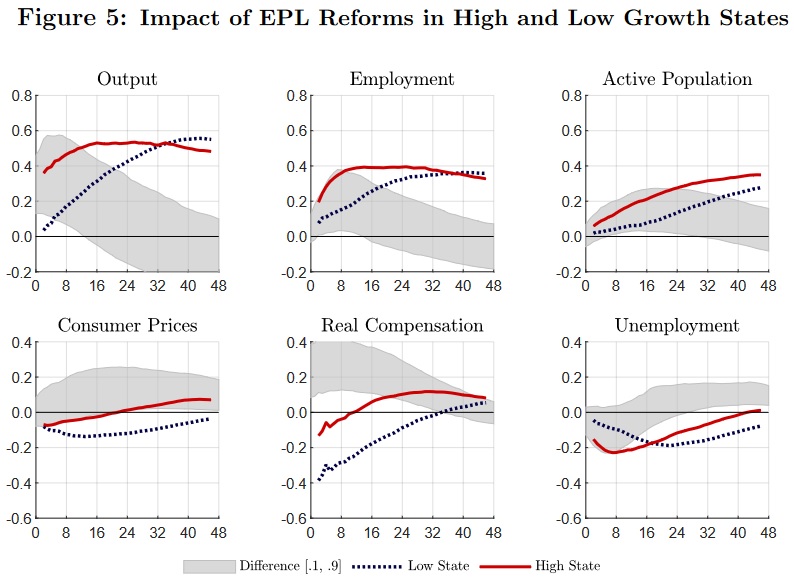

By the way, a study from the Bank for International Settlements, published well before coronavirus became an issue, notes other negative effects of unemployment benefits.

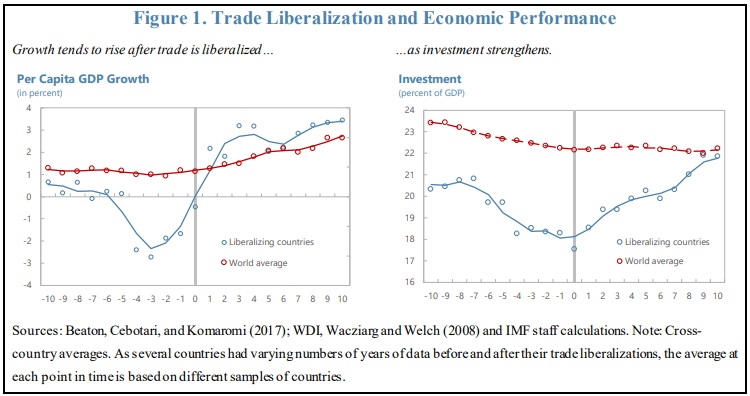

Many countries provide unemployment insurance (UI) to reduce individuals’ income risk and to moderate fluctuations in the economy. However, to the extent that these policies are successful,  they would be expected to reduce precautionary savings and hence bank deposits–households’ main saving instrument. In this paper, we study this reduced incentive to save and uncover a novel distortionary mechanism through which UI policies affect the economy. In particular, we show that, when UI benefits become more generous, bank deposits fall. Since deposits are the main stable funding source for banks, this fall in deposits squeezes bank commercial lending, which in turn reduces corporate investment.

they would be expected to reduce precautionary savings and hence bank deposits–households’ main saving instrument. In this paper, we study this reduced incentive to save and uncover a novel distortionary mechanism through which UI policies affect the economy. In particular, we show that, when UI benefits become more generous, bank deposits fall. Since deposits are the main stable funding source for banks, this fall in deposits squeezes bank commercial lending, which in turn reduces corporate investment.

Just another chapter in the government’s book on how to discourage savings.

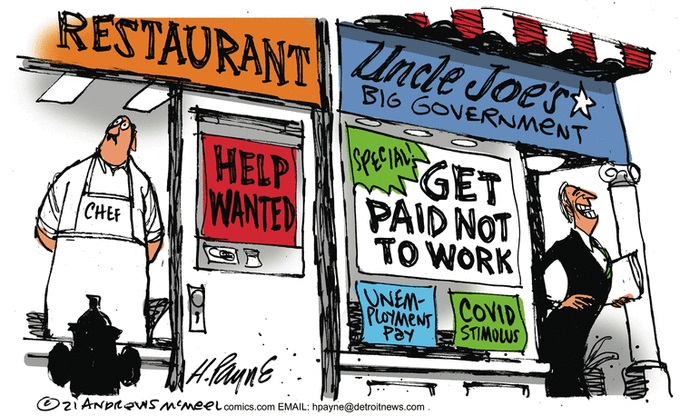

Let’s close with some real world illustrations of how Washington’s approach is backfiring.

A story from National Public Radio shows how workers respond logically to perverse incentives.

…the extra money can create some awkward situations. Some businesses that want to keep their doors open say it’s hard to do so when employees can make more money by staying home. “We basically have this situation where it would be a logical choice for a lot of people to be unemployed,” said Sky Marietta, who opened a coffee shop along with her husband, Geoff, last year in Harlan, Ky. …The shop had been up and running for only a few months when the coronavirus hit. …Marietta was determined to stay open. …But even though she had customers, Marietta reluctantly decided to close the coffee shop just over a week ago. “The very people we hired have now asked us to be laid off,” Marietta wrote… “Not because they did not like their jobs or because they did not want to work, but because it would cost them literally hundreds of dollars per week to be employed.” …the $10 to $15 an hour they’d make serving coffee is no match for the new jobless benefits.

who opened a coffee shop along with her husband, Geoff, last year in Harlan, Ky. …The shop had been up and running for only a few months when the coronavirus hit. …Marietta was determined to stay open. …But even though she had customers, Marietta reluctantly decided to close the coffee shop just over a week ago. “The very people we hired have now asked us to be laid off,” Marietta wrote… “Not because they did not like their jobs or because they did not want to work, but because it would cost them literally hundreds of dollars per week to be employed.” …the $10 to $15 an hour they’d make serving coffee is no match for the new jobless benefits.

Maxim Lott also wrote about another tragic example.

An additional $600 per week in unemployment benefits…causing concern that some workers could be in a position to actually make more money by leaving their jobs. . …That angers some essential workers on the front lines on the crisis. “I can tell you as a worker who barely makes over minimum wage, at $12 an hour, the whole thing is complete BS,” Otis Mitchell Jr., who works in West Virginia transporting hospital patients to get medical tests, told Fox News. Mitchell Jr. added that he has unemployed friends who already are getting the extra $600, and that “I prefer to work, but sadly I’d make more staying home.” …generous payments are…scheduled to last for four months, ending July 31.

the whole thing is complete BS,” Otis Mitchell Jr., who works in West Virginia transporting hospital patients to get medical tests, told Fox News. Mitchell Jr. added that he has unemployed friends who already are getting the extra $600, and that “I prefer to work, but sadly I’d make more staying home.” …generous payments are…scheduled to last for four months, ending July 31.

A report from CNBC also found perverse consequences.

Jamie Black-Lewis felt like she won the lottery after getting two forgivable loans through the Paycheck Protection Program. …When Black-Lewis convened a virtual employee meeting to explain her good fortune, she expected jubilation and relief that paychecks would resume in full even though the staff — primarily hourly employees — couldn’t work. She got a different reaction. “It was a firestorm of hatred about the situation,” Black-Lewis said. …The anger came from employees who’d determined they’d make more money by collecting unemployment benefits than their normal paychecks. …“I couldn’t believe it,” she added. “On what planet am I competing with unemployment?”

she expected jubilation and relief that paychecks would resume in full even though the staff — primarily hourly employees — couldn’t work. She got a different reaction. “It was a firestorm of hatred about the situation,” Black-Lewis said. …The anger came from employees who’d determined they’d make more money by collecting unemployment benefits than their normal paychecks. …“I couldn’t believe it,” she added. “On what planet am I competing with unemployment?”

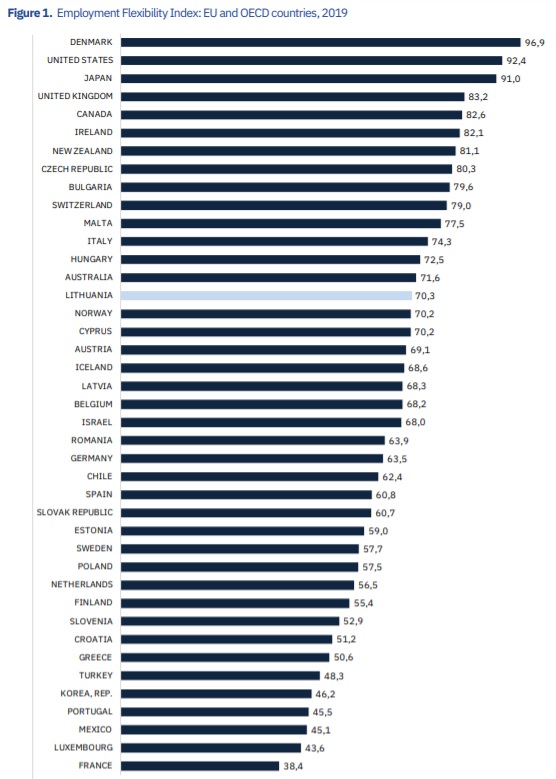

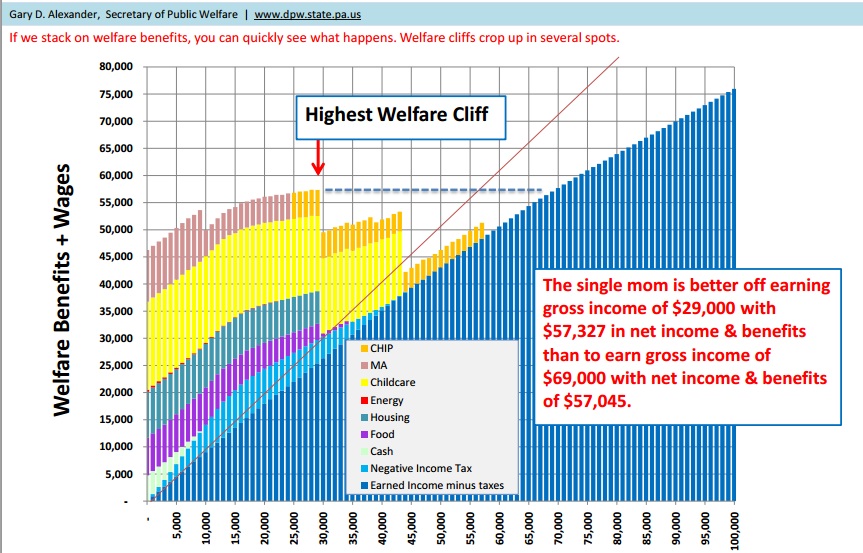

If you want to see why people are choosing unemployment, here’s a chart from the CNBC story. Using examples from three states, it shows the normal generosity of unemployment benefits on the left and the new approach on the right.

Needless to say, it’s economic malpractice to make unemployment more attractive than jobs paying $20-$30 per hour.

It’s the real-world version of this satirical Wizard-of-Id cartoon.

P.S. Speaking of satire, Nancy Pelosi actually argued that paying people not to work was a form of stimulus.

P.P.S. Here are a couple of anecdotes, one from Ohio and one from Michigan, about the perverse impact of excessive unemployment benefits during the last downturn.

P.P.P.S. If you want more academic literature on the relationship between government benefits and joblessness, click here and here.

Read Full Post »

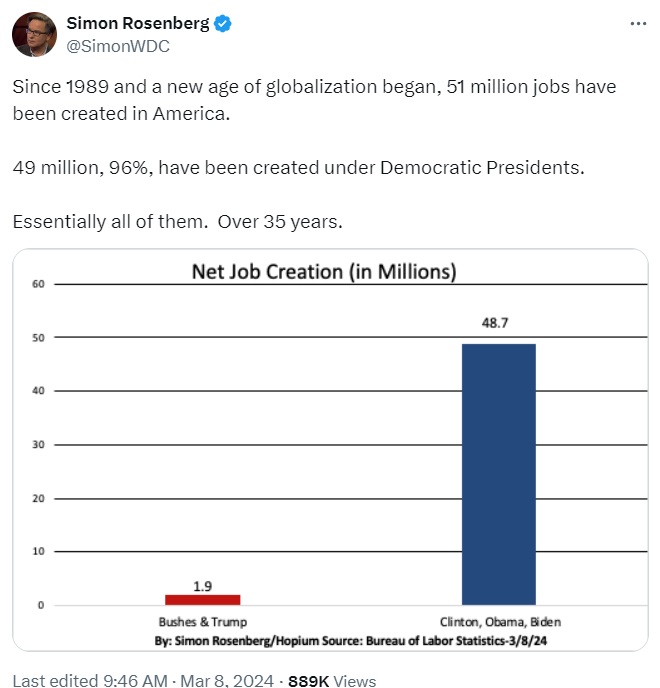

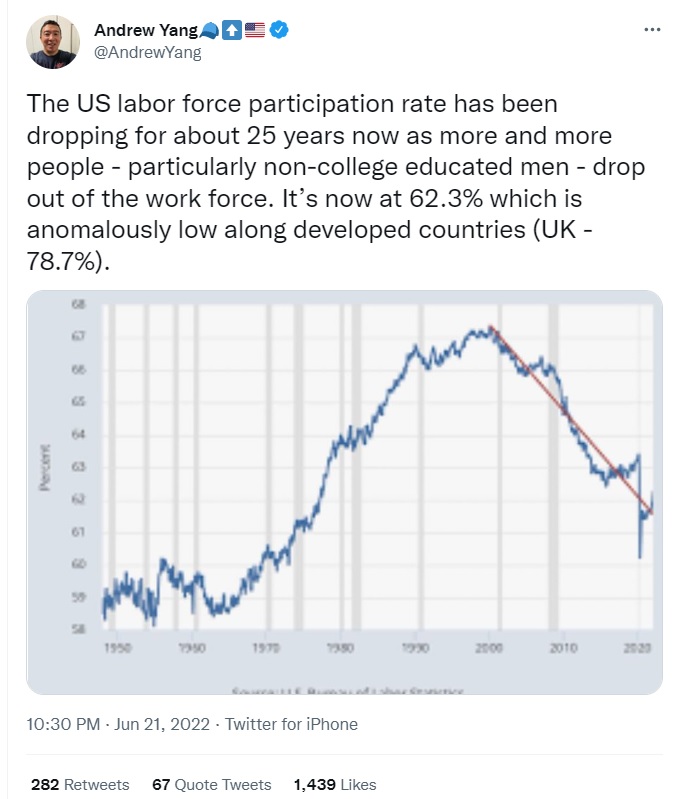

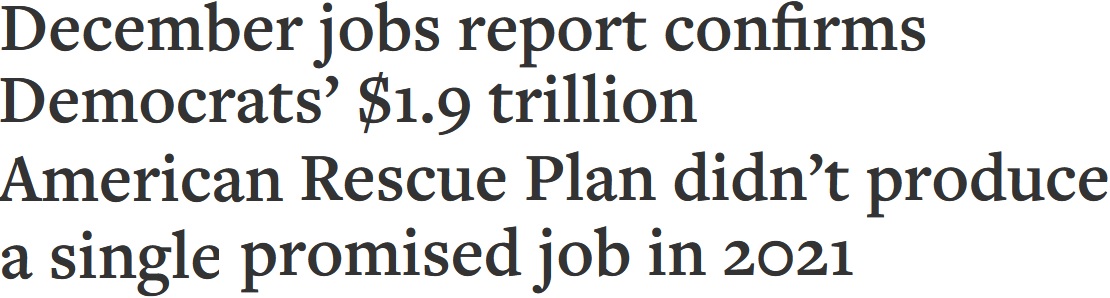

…What is the catch? Attributing job creation to policies or presidents isn’t as clear as it might seem. The Republican Congress of 1995 to 2001 might deserve a share of the credit for the job growth under Clinton… In crises especially, the parties have historically worked together. When faced with the 2008 financial crisis and the coronavirus pandemic, George W. Bush and Trump “chose the policy responses that Democrats favored,” said Dan Mitchell, a libertarian economist. …Also, Rosenberg chose a favorable time frame for Democrats. …Job creation under each president also depends on luck. …In one recent example, the number of jobs created under Trump would have been higher had a once-in-a-century pandemic not hit during his fourth year in office.