I periodically use a “most depressing” theme when writing about charts or tweets with grim data.

I’ve done that with regional data and also looked at depressing data from specific countries.

Today, we’re going to look at some “most depressing” information about the United States. Here’s a tweet from Yale Professor Alice Evans about labor force participation for working-age men in developed nations.

Let’s start by emphasizing that that the labor force participation rate (or the employment-population ratio, for those who prefer that data set) is a more important indication than the unemployment rate.

After all, our prosperity is tied to the quantity and quality of labor and capital in the economy. Which leads me to three observations.

- It is definitely bad news when labor force participation declines over time.

- It is even worse news when it declines for men in their prime working years.

- And it is utterly depressing when the United States falls behind other nations.

David Bahnsen has a new article in National Review on the topic of declining labor force participation. Here are a few excerpts. starting with some straight-forward economic analysis.

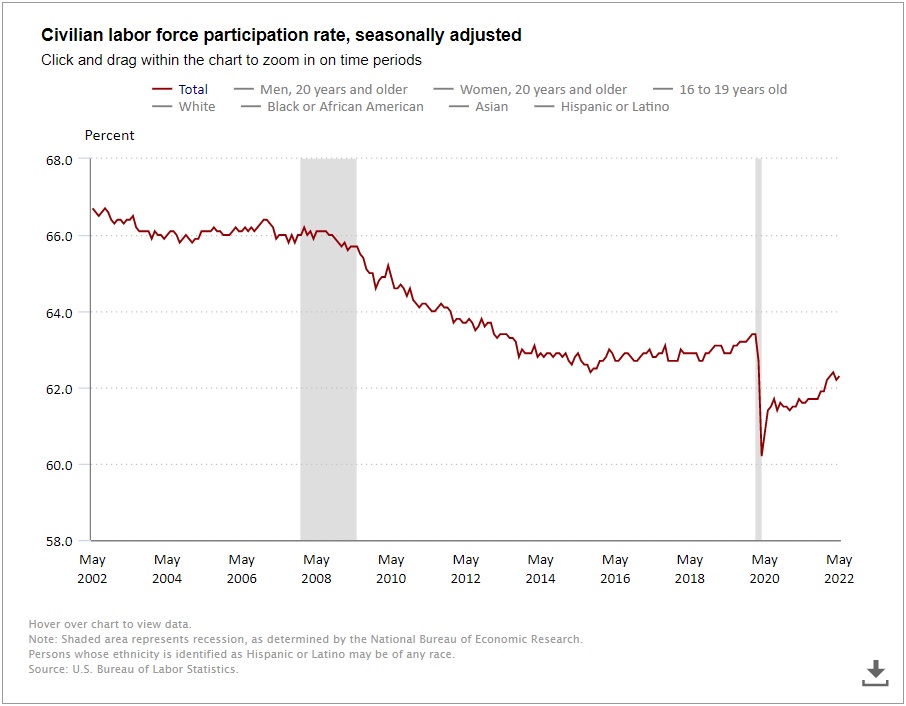

The labor-force participation rate (those working combined with those actively looking for work as a percentage of the non-institutionalized, working-age population) was steady and reliably around 66 or 67 percent for years before the financial crisis. The number dropped to between 62 and 63 percent after that and only started to trend higher after the deregulation and tax reform of 2017–18.

That, of course, was upended by Covid and the 2020 shutdowns. …That problem is the failure of the labor-force participation rate to return to normal. At approximately 62 percent, we sit 1.5 percentage points below pre-Covid levels… While 1.5 percentage points may seem like a small number, with a working-age population of about 260 million people, it means we are about 4 million people below the trend-line… And paradoxically, this comes with more job openings than we have people looking for jobs.

This is an economic problem, but it should raise alarm bells for other reasons as well.

Simply stated, the decline in labor force participation may be a sign of eroding societal capital.

The American ethos values the dignity of work and sees purpose, meaning, and hope in productive activity. Not only does our economy desperately need the full weight of American ingenuity, innovation, and productivity, but our souls do as well. In a time of increased alienation, isolation, and desperation, a larger labor force would mean a greater number of people engaged in meaningful activity with attendant duties and responsibilities. It would allow for less substance abuse, less emotional angst, and more pursuits of passions. …Our goal must be not only maximum employment of those looking for work, but also that more people who are able to participate in the labor force actually do so. …A labor-force participation rate equal to our pre-2008 levels is attainable, but not without a resurgence of values focused on productivity. The end result would be far more meaningful than what we find in a GDP calculation.

He’s right, in my not-so-humble opinion.

Which raises the question of why the U.S. numbers are bad and what can be done to reverse the decline?

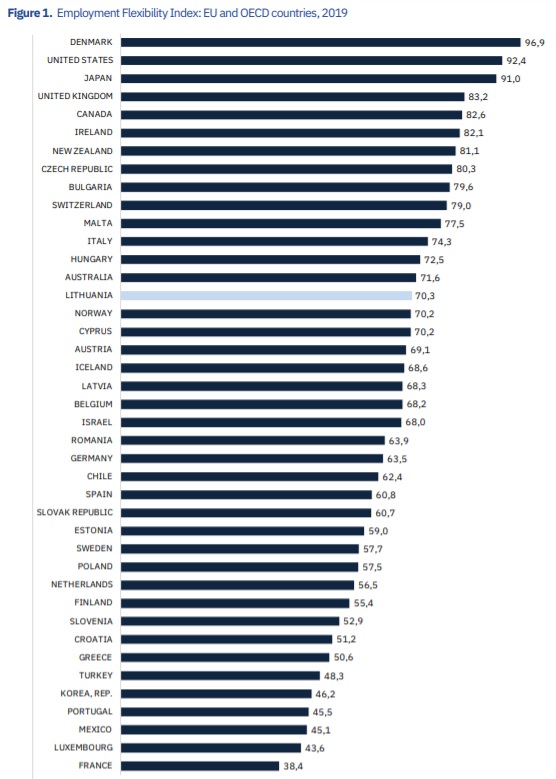

At the risk of admitting uncertainty, I’m not sure we have easy answers. For instance, I’m tempted to say the numbers will improve if we address some of the ways (subsidized unemployment, lax disability rules, licensing laws, etc).

But presumably those problems exist in the other nations in the chart. Indeed, most of those countries presumably have policies that are worse (such as bigger welfare states) than what we have in the United States.

Which means societal capital may be the problem (even though conventional measures suggest the U.S. ranks highly by world standards).