At the end of last month, I wrote about the growth-maximizing size of government, citing a study that estimated that the public sector in Sudan should not consume more than 11.17 percent of the nation’s economic output.

I realize that very few people care about Sudanese fiscal policy, but the research gave me an opportunity to condemn the OECD, IMF, and UN for peddling the nonsensical argument that more government spending would promote faster growth in poor nations.

I realize that very few people care about Sudanese fiscal policy, but the research gave me an opportunity to condemn the OECD, IMF, and UN for peddling the nonsensical argument that more government spending would promote faster growth in poor nations.

Today, I want to cite another study, in this case about the growth-maximizing size of government in India. But, once again, I’m citing some research to make a bigger point.

First, here are the findings from the study, written by Neha Jain and Niharika Sinha.

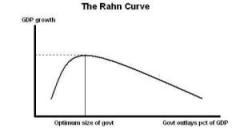

The present study aims to examine the relationship between government size and economic growth in India for the period from 1961 to 2018. Additionally, as a novel contribution, the current study also attempts to examine the existence of Armey curve and estimate the threshold level of government size in India.

…The result of the study confirms…the existence of Armey curve and supports the Armey curve hypothesis in India. There exists a positive impact of government size till the threshold level, and beyond the threshold level, the coefficient of economic growth tends to decrease. The estimated optimal government size is 11.89% for India…the findings of the study also suggest that a large size of the government can be harmful for the efficiency of economic growth; thus, adjusting the government at its optimum is crucial to the economy.

By the way, the Armey Curve is the Rahn Cure and the Rahn Curve is the Armey Curve (there’s ongoing discussion of who was the first to visually depict the upside-down-U-shaped relationship between the size of government and economic performance).

But let’s set aside that discussion. Regardless of who deserves credit, it’s vitally important that policymakers understand that excessive government spending is very harmful for prosperity.

That’s true in India, and that’s true in the United States (especially since government is too big right now and is expected to become a bigger burden in the future).

But while it’s good to have a discussion on the quantity of government spending, let’s not forget that the quality of government spending also matters.

To be more precise, some types of government spending can be helpful to growth and other types of spending are usually harmful to growth.

- Rule-of-law spending – If done effectively, spending for pure public goods such as administration of justice and enforcement of contracts can create a favorable environment for more growth.

- Physical capital spending – The growth impact (or anti-growth impact) depends on whether money for ports, roads, etc, is spent efficiently, thus offsetting the cost of diverting resources from the economy’s productive sector.

- Human capital spending – The growth impact (or anti-growth impact) depends on whether money for education, training, etc, is spent efficiently, thus offsetting the cost of diverting resources from the economy’s productive sector.

- Defense/military spending – May be necessary for national survival, but otherwise bad for growth since labor and capital are diverted from the economy’s productive sector to government.

- Social welfare spending – May be compassionate (or dependency inducing), but otherwise bad for growth since labor and capital are diverted from the productive sector to government.

The purpose of today’s column is to conceptually explain how different types of government spending may or many not affect economic performance, but I can’t resist noting that the United States does a terrible job of spending money on human capital and physical capital.

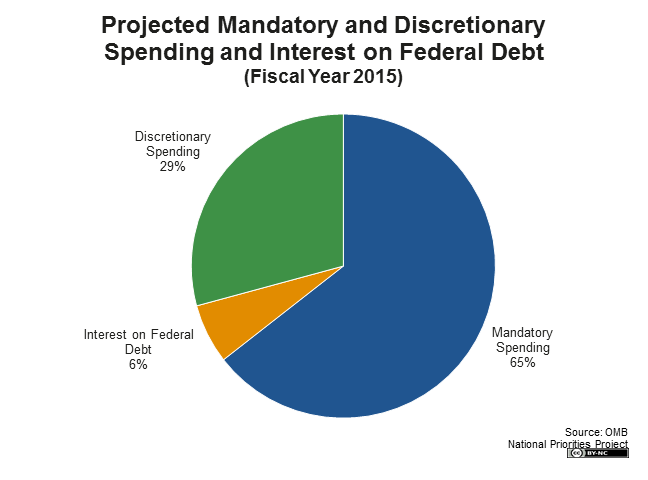

And I can’t resist observing that the vast majority of America’s federal budget is for social welfare spending.

P.S. Developing nations do a bad job of providing rule of law, but I have near-zero faith that more government spending will lead to improvements. Instead, more spending will be a vehicle for ruling elites to cement their power by buying votes.

Good question! When you put it that way, it does seem pretty perverse. …Here’s what the world looks like to the Cato Institute… Don’t worry about exactly how we’re quantifying these things. The point is just this: according to the chart, the more Swedish you are, the worse off your country is. The Swedes, no fools, have figured this out and are launching their northwestward climb toward free-market prosperity.

Good question! When you put it that way, it does seem pretty perverse. …Here’s what the world looks like to the Cato Institute… Don’t worry about exactly how we’re quantifying these things. The point is just this: according to the chart, the more Swedish you are, the worse off your country is. The Swedes, no fools, have figured this out and are launching their northwestward climb toward free-market prosperity. This picture gives very different advice about how Swedish we should be. Where do we find peak prosperity? At a point more Swedish than America, but less Swedish than Sweden. If this picture is right, it makes perfect sense for Obama to beef up our welfare state while the Swedes trim theirs down.

This picture gives very different advice about how Swedish we should be. Where do we find peak prosperity? At a point more Swedish than America, but less Swedish than Sweden. If this picture is right, it makes perfect sense for Obama to beef up our welfare state while the Swedes trim theirs down.

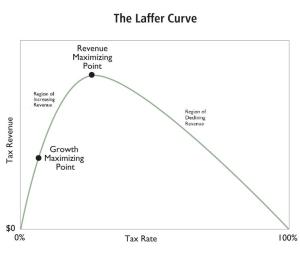

As this simple chart illustrates, the Rahn Curve is sort of the spending equivalent of

As this simple chart illustrates, the Rahn Curve is sort of the spending equivalent of  But I’m digressing. Let’s get back to the research from the Bank of Finland. The author makes a very sensible point that even modest reductions in the burden of government can yield positive results – sort of like going from Point A to Point B on the Rahn Curve.

But I’m digressing. Let’s get back to the research from the Bank of Finland. The author makes a very sensible point that even modest reductions in the burden of government can yield positive results – sort of like going from Point A to Point B on the Rahn Curve.

Institute’s Richard Rahn, the Curve shows that modest amounts of government spending – for core “public goods” such as rule of law and protection of property rights – is associated with better economic performance.

Institute’s Richard Rahn, the Curve shows that modest amounts of government spending – for core “public goods” such as rule of law and protection of property rights – is associated with better economic performance.