I’m a big fan of the Baltic nations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania.

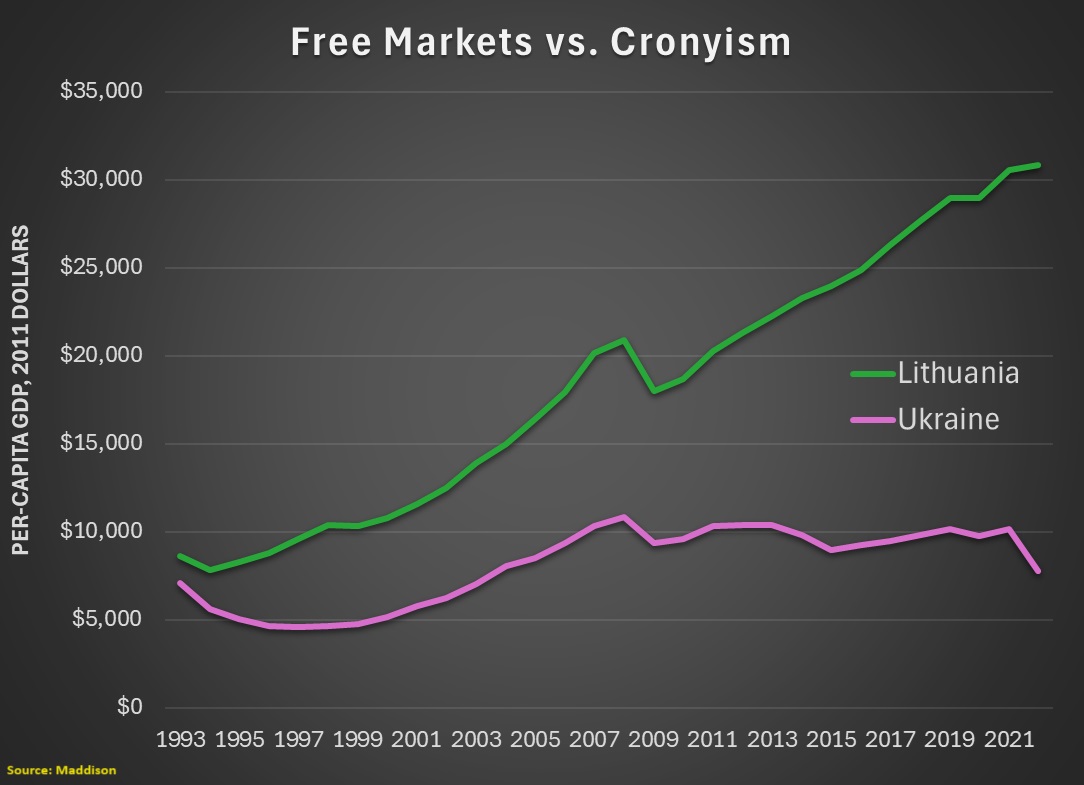

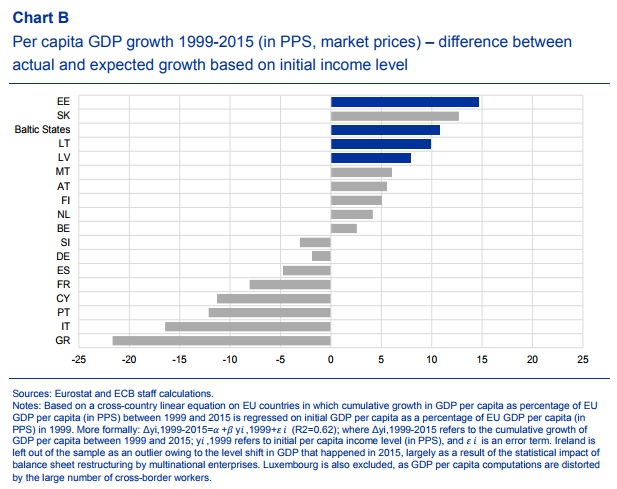

These three countries emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Empire and they have taken advantage of their independence to become successful market-driven economies.

One key to their relative success is tax policy. All three nations have flat taxes. Estonia’s system is so good (particularly its approach to business taxation) that the Tax Foundation ranks it as the best in the OECD.

And the Baltic nations all deserve great praise for cutting the burden of government spending in response to the global financial crisis/great recession (an approach that produced much better results than the Keynesian policies and/or tax hikes that were imposed in many other countries).

And the Baltic nations all deserve great praise for cutting the burden of government spending in response to the global financial crisis/great recession (an approach that produced much better results than the Keynesian policies and/or tax hikes that were imposed in many other countries).

But good policy in the past is no guarantee of good policy in the future, so it is with great dismay that I share some very worrisome news from two of the three Baltic countries.

First, we have a grim update from Estonia, which may be my favorite Baltic nation if for no other reason than the humiliation it caused for Paul Krugman. But now Estonia may cause sadness for me. The coalition government in Estonia has broken down and two of the political parties that want to lead a new government are hostile to the flat tax.

Estonia’s government collapsed Wednesday after Prime Minister Taavi Roivas lost a confidence vote in Parliament, following months of Cabinet squabbling mainly over economic policies. …Conflicting views over taxation and improving the state of Estonia’s economy, which the two junior coalition partners claim is stagnant, is the main cause for the breakup. …The core of those policies is a flat 20 percent tax on income. The Social Democrats say the wide income gaps separating Estonia’s different social groups would best be narrowed by introducing Nordic-style progressive taxation. The two parties said Wednesday that they will immediately start talks on forming a coalition with the Center Party, Estonia’s second-largest party, which is favored by the country’s sizable ethnic-Russian majority and supports a progressive income tax.

And Lithuanians just held an election and

the outcome does not bode well for that nation’s flat tax.

After the weekend run-off vote, which followed a first round on October 9, the centrist Lithuanian Peasants and Green Union party LGPU) ended up with 54 seats in the 141-member parliament. …The conservative Homeland Union, which had been tipped to win, scored a distant second with 31 seats, while the governing Social Democrats were, as expected, relegated to the opposition, with just 17 seats. …The LPGU wants to change a controversial new labour code that makes it easier to hire and fire employees, impose a state monopoly on alcohol sales, cut bureaucracy, and above all boost economic growth to halt mass emigration. …Promises by Social Democratic Prime Minister Butkevicius of a further hike in the minimum wage and public sector salaries fell flat with voters.

The Social Democrats sound like they had some bad idea, but the new LGPU government has a more extreme agenda. It already has proposed to create a special 4-percentage point surtax on taxpayers earning more than €12,000 annually (the government also wants to expand double taxation, which also is contrary to the tax-income-only-once principle of a pure flat tax).

So the bad news is that the flat tax could soon disappear in Estonia and Lithuania.

But the good news, based on my discussions with people in these two nations, is that the battle isn’t lost. At least not yet.

In both cases, policy can’t be changed unless all parties in the coalition government agree. Fortunately, they haven’t reached that point.

And hopefully that point will never be reached if Estonia and Lithuania want long-run success.

And hopefully that point will never be reached if Estonia and Lithuania want long-run success.

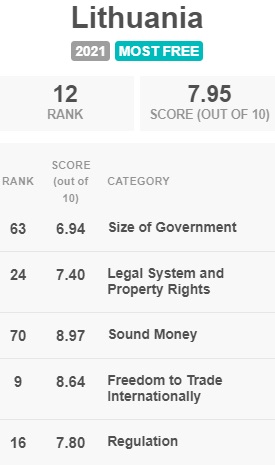

All of the Baltic nations get reasonably good scores from Economic Freedom of the World. Ditching the flat tax will cause their scores to decline.

Given that fiscal policy is only 20 percent of a nation’s grade, adopting some bad tax policy may not seem like the end of the world.

But the flat tax isn’t just good policy. It also has symbolic value, telling both domestic entrepreneurs and global investors that a country has a commitment to a system that won’t impose extra punishment just because a person contributes more to national economic output.

By the way, the LPGU Party is very correct to worry about emigration. The Baltic nations (like most countries in Eastern Europe) face a very large demographic problem. And every time a young person leaves for better opportunities elsewhere (even if that better opportunity is a big welfare check), that makes the long-run outlook even more challenging.

But imposing a more punitive tax system is exactly the opposite of what should happen if the goal is faster growth so that people don’t leave the nation.

Let’s close with a famous quote from John Ramsay McCulloch, a Scottish economist from the 1800s.

To be sure, progressive taxation didn’t lead to total catastrophe, so McCulloch’s warning may seem overwrought by today’s standards.

But the so-called progressive income tax did lead to the modern welfare state. And the modern welfare state, when combined with demographic change, is threatening immense economic and societal damage in many nations.

So what he wrote in 1863 may turn out to be very prescient for historians in 2063 who wonder why the western world collapsed.

P.S. If Estonia and Lithuania move in the wrong direction, Latvia could be a big winner. That nation already has received some positive attention for being fiscally responsible, and it also has withstood pressure from the IMF to impose bad tax policy. So Latvia is well positioned to reap the benefits if Estonia and Lithuania shoot themselves in the foot.

Read Full Post »

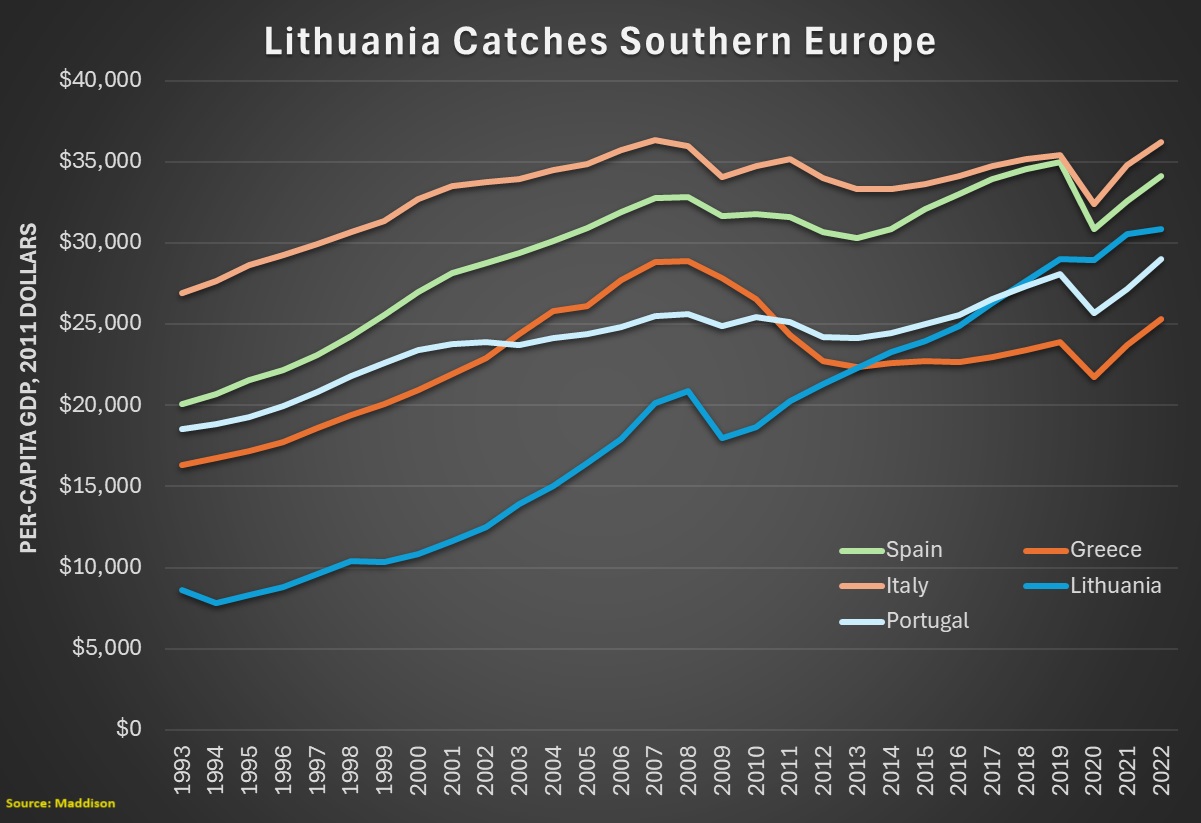

…The transition from being part of a command economy to being a part of a market economy is never easy. The Lithuanian transition involved a succession of shocks: the collapse of the Soviet Union; the 2008 financial crisis… Since Lithuania joined the EU in 2004, its real GDP per capita has grown faster than any EU country other than the Czech Republic. In terms of purchasing power parity GDP per capita grew by 229% between 2004 and 2020. …Lithuania is…a great success story…for liberal ideas such as democracy and the free market that have taken root in Russia’s shadow.