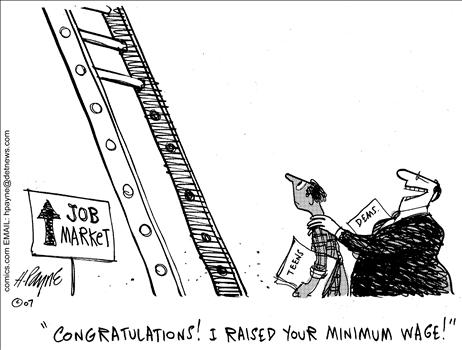

Frederic Bastiat, the great French economist (yes, such creatures used to exist) from the 1800s, famously observed that a good economist always considers both the “seen” and “unseen” consequences of any action.

A sloppy economist looks at the recipients of government programs and declares that the economy will be stimulated by this additional money that is easily seen, whereas a good economist recognizes that the government can’t redistribute money without doing unseen damage by first taxing or borrowing it from the private sector.

can’t redistribute money without doing unseen damage by first taxing or borrowing it from the private sector.

A sloppy economist looks at bailouts and declares that the economy will be stronger because the inefficient firms that stay in business are easily seen, whereas a good economist recognizes that such policies imposes considerable unseen damage by promoting moral hazard and undermining the efficient allocation of labor and capital.

We now have another example to add to our list. Many European nations have “social protection” laws that are designed to shield people from the supposed harshness of capitalism. And part of this approach is so-called Employment Protection Legislation, which ostensibly protects workers by, for instance, making layoffs very difficult.

The people who don’t get laid off are seen, but what about the unseen consequences of such laws?

Well, an academic study from three French economists has some sobering findings for those who think regulation and “social protection” are good for workers.

…this study proposes an econometric investigation of the effects of the OECD Employment Protection Legislation (EPL) indicator… The originality of our paper is to study the effects of labour market regulations on capital intensity, capital quality and the share of employment by skill level using a symmetric approach for each factor using a single original large database: a country-industry panel dataset of 14 OECD countries, 18 manufacturing and market service industries, over the 20 years from 1988 to 2007.

One of the findings from the study is that “EPL” is an area where the United States historically has always had an appropriately laissez-faire approach (which also is evident from the World Bank’s data in the Doing Business Index).

Here’s a chart showing the US compared to some other major developed economies.

It’s good to see, by the way, that Denmark, Finland, and the Netherlands engaged in some meaningful reform between 1994-2006.

But let’s get back to our main topic. What actually happens when nations have high or low levels of Employment Protection Legislation?

According to the research of the French economists, high levels of rules and regulations cause employers to substitute capital for labor, with low-skilled workers suffering the most.

Our main estimation results show an EPL effect: i) positive for non-ICT physical capital intensity and the share of high-skilled employment; ii) non-significant for ICT capital intensity; and (iii) negative for R&D capital intensity and the share of low-skilled employment. These results suggest that an increase in EPL would be considered by firms to be a rise in the cost of labour, with a physical capital to labour substitution impact in favour of more non-sophisticated technologies and would be particularly detrimental to unskilled workers. Moreover, it confirms that R&D activities require labour flexibility. According to simulations based on these results, structural reforms that lowered EPL to the “lightest practice”, i.e. to the US EPL level, would have a favourable impact on R&D capital intensity and would be helpful for unskilled employment (30% and 10% increases on average, respectively). …The adoption of this US EPL level would require very largescale labour market structural reforms in some countries, such as France and Italy. So this simulation cannot be considered politically and socially realistic in a short time. But considering the favourable impact of labour market reforms on productivity and growth. …It appears that labour regulations are particularly detrimental to low-skilled employment, which is an interesting paradox as one of the main goals of labour regulations is to protect low-skilled workers. These regulations seem to frighten employers, who see them as a labour cost increase with consequently a negative impact on low-skilled employment.

There’s a lot of jargon in the above passage for those who haven’t studied economics, but the key takeaway is that employment for low-skilled workers would jump by 10 percent if other nations reduced labor-market regulations to American levels.

Though, as the authors point out, that won’t happen anytime soon in nations such as France and Italy.

Now let’s review an IMF study that looks at what happened when Germany substantially deregulated labor markets last decade.

After a decade of high unemployment and weak growth leading up to the turn of the 21th century, Germany embarked on a significant labor market overhaul. The reforms, collectively known as the Hartz reforms, were put in place in three steps between January 2003 and January 2005. They eased regulation on temporary work agencies, relaxed firing restrictions, restructured the federal employment agency, and reshaped unemployment insurance to significantly reduce benefits for the long-term unemployed and tighten job search obligations.

And when the authors say that long-term unemployment benefits were “significantly” reduced, they weren’t exaggerating.

Here’s a chart from the study showing the huge cut in subsidies for long-run joblessness.

So what were the results of the German reforms?

To put it mildly, they were a huge success.

…the unemployment rate declined steadily from a peak of almost 11 percent in 2005 to five percent at the end of 2014, the lowest level since reunification. In contrast, following the Great Recession other advanced economies — particularly in the euro area — experienced a marked and persistent increase in unemployment. The strong labor market helped Germany consolidate its public finances, as lower outlays on unemployment benefits resulted in lower spending while stronger taxes and social security contribution pushed up revenues.

Gee, what a shocker. When the government stopped being as generous to people for being unemployed, fewer people chose to be unemployed.

Which is exactly what happened in the United States when Congress finally stopped extending unemployment benefits.

And it’s also worth noting that this was also a period of good fiscal policy in Germany, with the burden of spending rising by only 0.18 percent annually between 2003-2007.

But the main lesson of all this research is that some politicians probably have noble motives when they adopt “social protection” legislation. In the real world, however, there’s nothing “social” about laws and regulations that either discourage employers from hiring people and or discourage people from finding jobs.

P.S. Another example of “seen” vs “unseen” is how supposedly pro-feminist policies actually undermine economic opportunity for women.