I don’t like bad monetary policy by central bankers.

I especially don’t like bad monetary policy when central bankers refuse to accept responsibility for their mistakes.

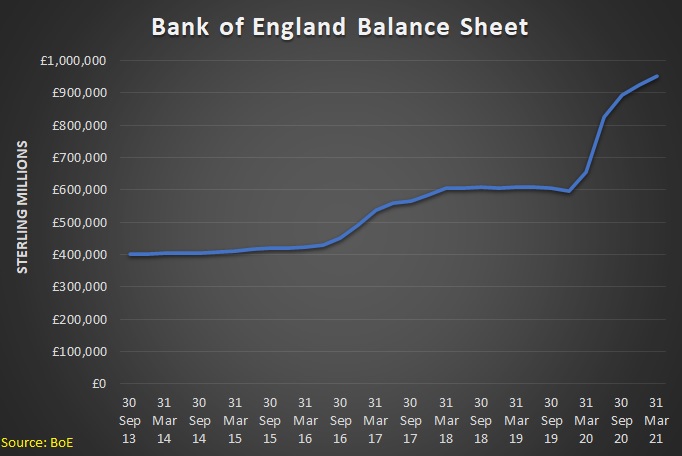

I’ve already written about blame-shifting by the Bank of England.

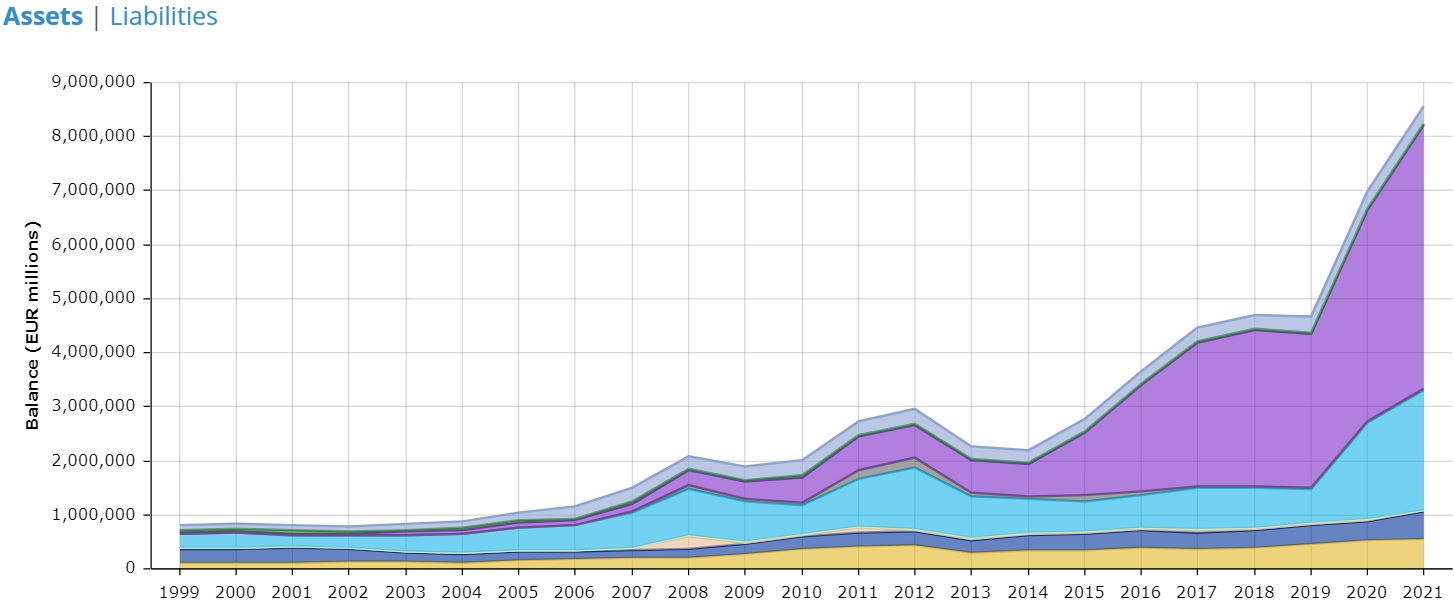

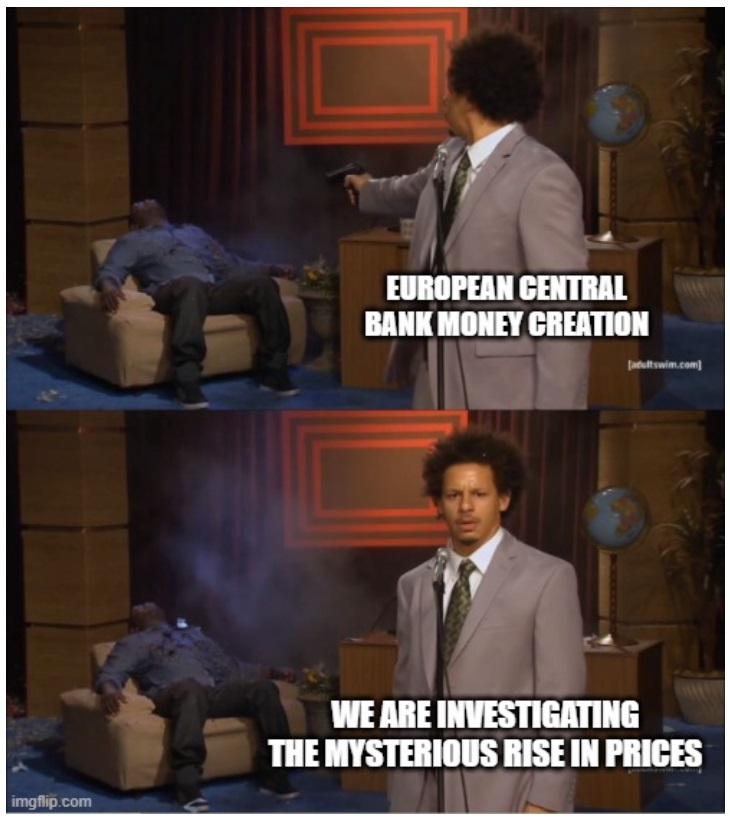

An even worse example comes from the European Central Bank. And I’m not referring to the vapid statement by the political hack in charge of the ECB.

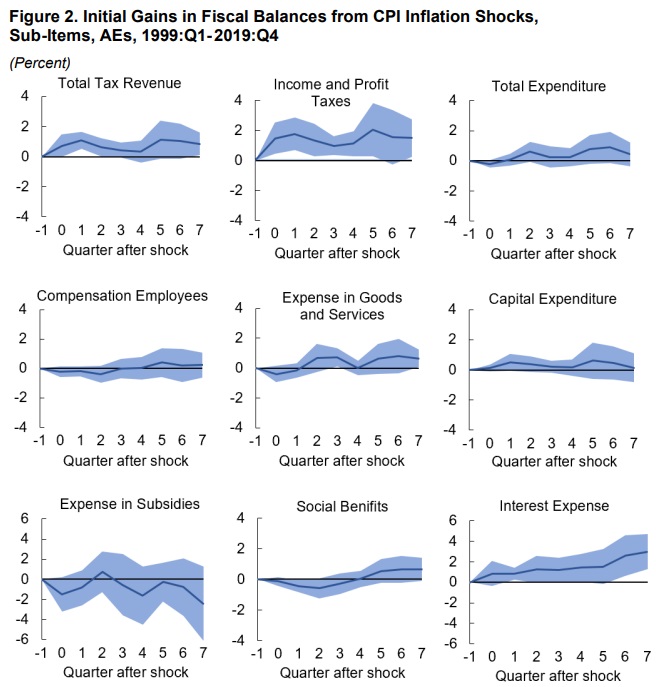

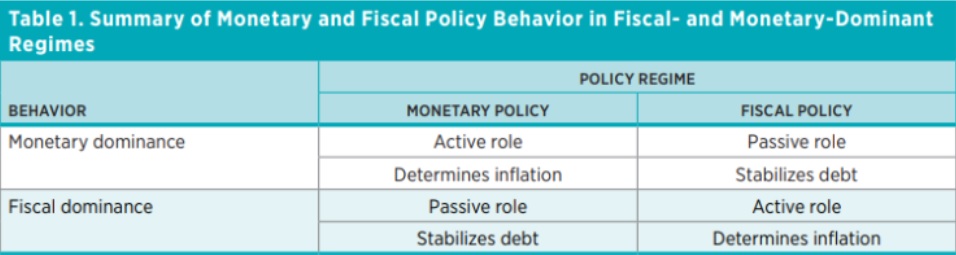

What’s far worse is that the supposedly professional economists at the ECB produced a study about the recent bout of inflation in the eurozone and pretended that it wasn’t a result of their own bad monetary policy.

That example was so egregious that I even created a meme to mock their lame effort to deflect blame.

Today, I want to do something similar. I’m motivated by a New York Times column by Bret Stephens.

Here are some excerpts.

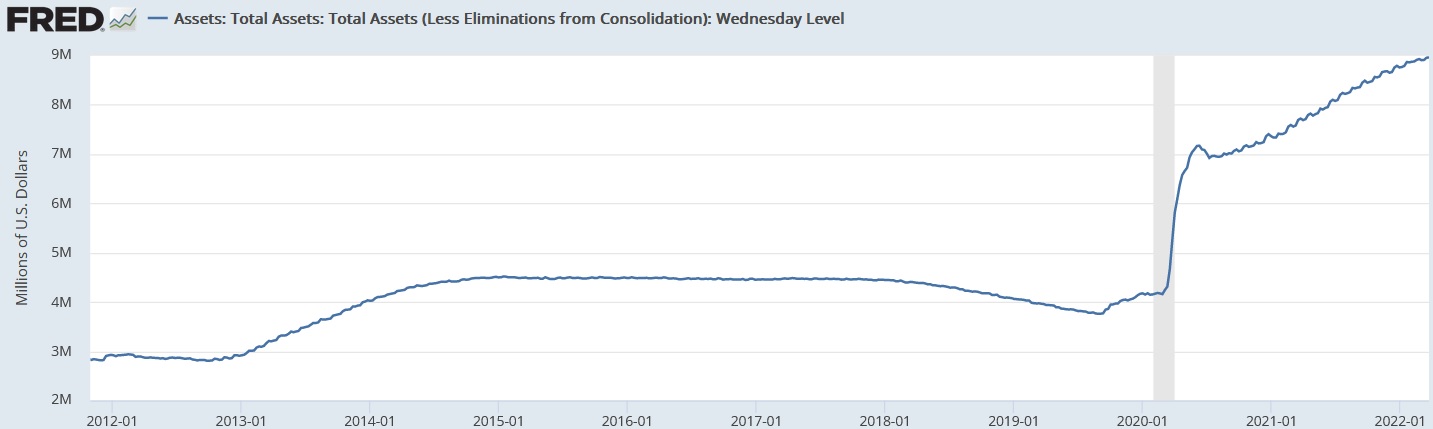

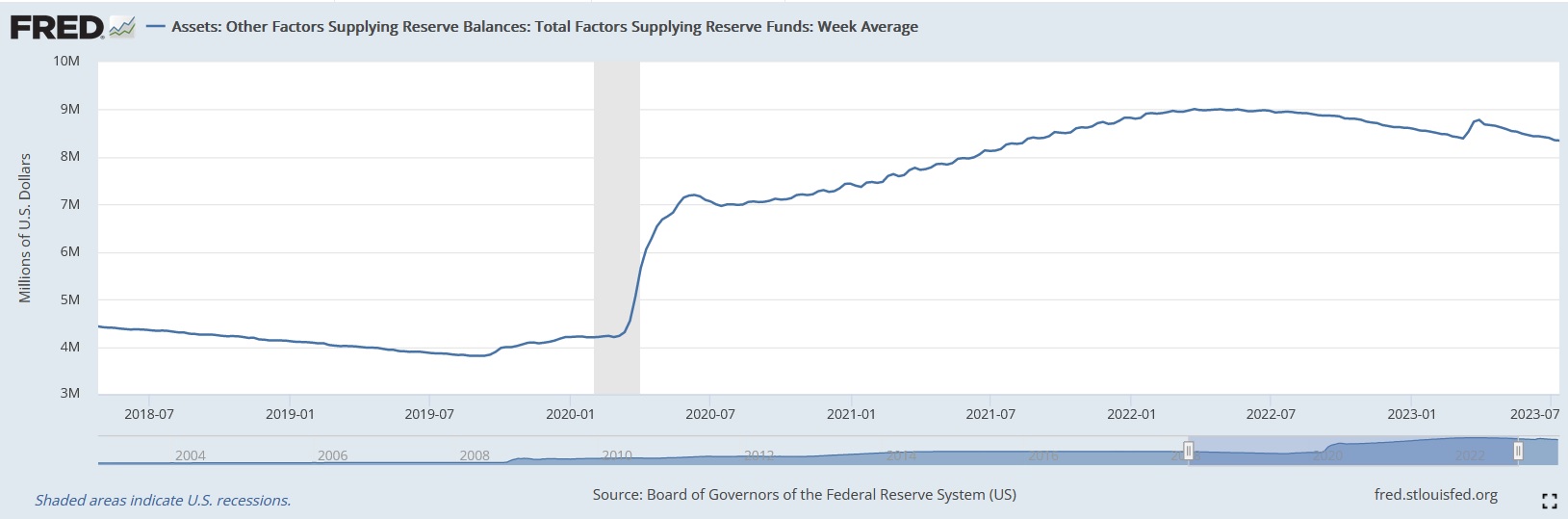

Why the broad dissatisfaction with an economic system that is supposed to offer unsurpassed prosperity? Ruchir Sharma, the chairman of Rockefeller International and a Financial Times columnist, has an answer that boils down to two words: easy money.

…“When the price of borrowing money is zero,” Sharma told me this week, “the price of everything else goes bonkers.” …In theory, easy money should have broad benefits for regular people, from employees with 401(k)s to consumers taking out cheap mortgages. In practice, it has destroyed much of what used to make capitalism an engine of middle-class prosperity… First, there was inflation in real and financial assets, followed by inflation in consumer prices, followed by higher financing costs as interest rates have risen to fight inflation… For wealthier Americans who own assets or had locked in low-interest mortgages, this hasn’t been a bad thing. But for Americans who rely heavily on credit, it’s been devastating.

But it’s not just overall asset inflation and price inflation.

Easy money also distorts relative prices in the economy.

Sharma noted more subtle damages. Since investors “can’t make anything on government bonds when those yields are near zero,” he said, “they take bigger risks, buying assets that promise higher returns, from fine art to high-yield debt of zombie firms, which earn too little to make even interest payments and survive by taking on new debt.” A recent Associated Press analysis found 2,000 of those zombies (once thought to be mainly a Japanese phenomenon) in the United States. …The hit to the overall economy comes in other forms, too: inefficient markets that no longer deploy money carefully to their most productive uses, large corporations swallowing smaller competitors and deploying lobbyists to bend government rules in their favor, the collapse of prudential economic practices. …the worst hit is to capitalism itself: a pervasive and well-founded sense that the system is broken and rigged, particularly against the poor and the young. “A generation ago, it took the typical young family three years to save up to the down payment on a home,” Sharma observes in the book. “By 2019, thanks to no return on savings, it was taking 19 years.”

There’s lots of good information and analysis in the column, but I’m galled at the implication that capitalism deserves the blame.

The column’s title is particularly irksome. How on earth can someone conclude that capitalism went “off the rails” when the topic is how the government’s bad monetary policy has caused damage?

To be fair to the author, editors are usually the ones who decide titles.

But there are parts of the column that rub me the wrong way, such as “dissatisfaction with an economic system that is supposed to offer unsurpassed prosperity” and “the worst hit is to capitalism itself: a pervasive and well-founded sense that the system is broken and rigged.”

Some readers may interpret those passages to mean that free markets somehow have failed.

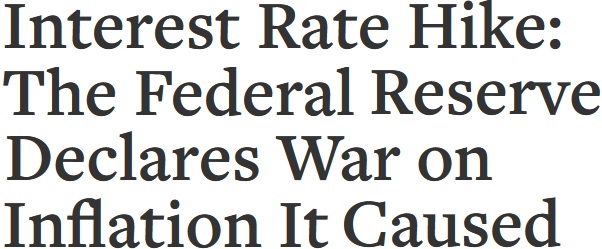

In reality, our “dissatisfaction” should be the Federal Reserve. And the Federal Reserve is the reason for the “well-founded sense that they system is broken and rigged.”

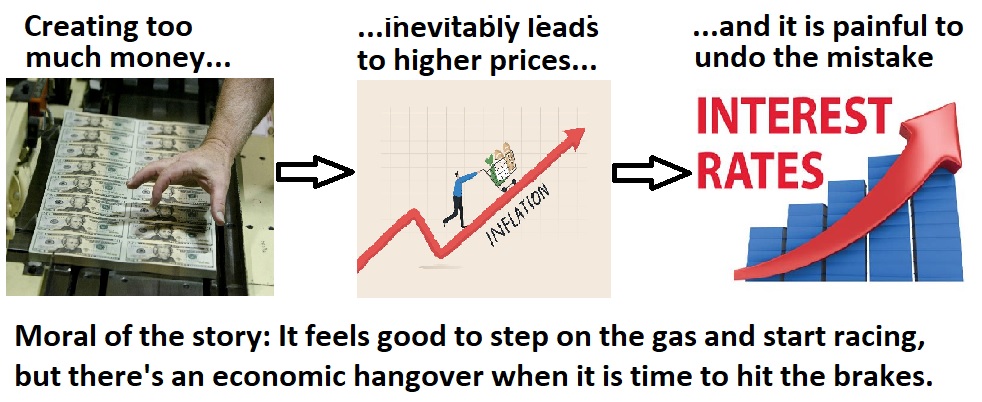

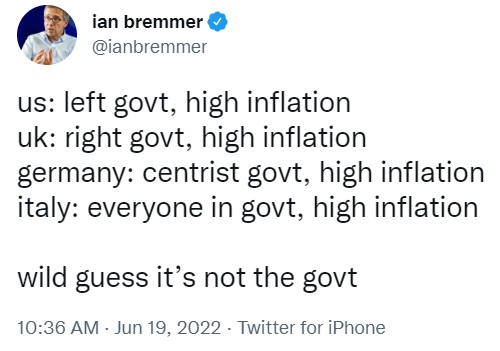

All of which goaded me to create a new meme.

I’ll close by stating that today’s column isn’t about America’s central bank shifting blame. But it would be very interesting to see what would happen if Jerome Powell (Chairman of the Federal Reserve) was asked what caused America’s recent bout of inflation.

There are three possible options.

- Admitting the Fed screwed up.

- Denying the Fed screwed up.

- Not understanding monetary policy.

I’m guessing we’d get a combination of #2 and #3, but I hope that’s wrong.

The bottom line is the Federal Reserve recently has been a net negative for America.

P.S. Sometimes the blame-shifting is by the politician who appoints the central bankers, as we saw earlier this year in Canada.