I’m a long-time advocate of “dynamic scoring,” which means I want the Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation to inform policy makers about how fiscal policy changes can impact overall economic performance and therefore generate “feedback” effects.

I also think the traditional approach, known as “static scoring,” creates a bias for bigger government because it falsely implies that ever-higher tax rates and an ever-growing burden of government spending don’t have any adverse impact on prosperity.

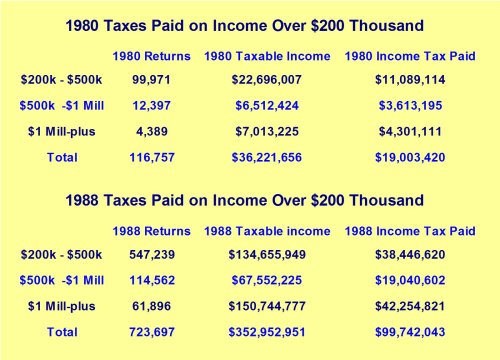

There’s a famous example to show the lunacy of static scoring. Back in late 1980s, former Oregon Senator Bob Packwood asked the Joint Committee on Taxation to estimate the revenue impact of a 100 percent tax rate on income over $200,000.

When considering such a proposal, any normal person with even the tiniest amount of common sense is going to realize that successful people quickly will figure out it makes no sense to either earn or report income about that level. As such, the government won’t collect any additional revenue.

Heck, it’s not just that the government won’t collect additional revenue. Our normal person with a bit of common sense is going to take the analysis one step further and conclude that revenues will plunge,  both because the government will lose the money it collected with the old income tax rates on income above $200,000 (i.e., the income that will disappear) and also because there will be all sorts of additional economic damage because of foregone work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship.

both because the government will lose the money it collected with the old income tax rates on income above $200,000 (i.e., the income that will disappear) and also because there will be all sorts of additional economic damage because of foregone work, saving, investment, and entrepreneurship.

But the JCT apparently didn’t have any bureaucrats with a shred of common sense. Because, as shown in Part II of my video series on the Laffer Curve, they predicted that such a tax would raise $104 billion in 1989, rising to $299 billion in 1993.

The good news is that both CBO and JCT are now seeking to incorporate some dynamic scoring into their fiscal estimates. Most recently, the CBO (with help from the JCT) released a report on the fiscal impact of repealing Obamacare.

Let’s look at what they did to see whether the bureaucrats did a good job.

I’ll start with something I don’t like. This new CBO estimate is fixated on the what will happen to deficit levels.

Here’s the main chart from the report. It compares what will happen to red ink if Obamacare is repealed, based on the static score (no macro feedback) and the dynamic score (with macro feedback).

There’s nothing wrong, per se, with this type of information. But making deficits the focus of the analysis is akin to thinking that the time of possession is more important than the final score in the Super Bowl.

What matters for more is what happens to the economy, which is affected by the size and structure of government. As such, here’s the most important finding from the report.

Repeal of the ACA would raise economic output…the resulting increase in GDP is projected to average about 0.7 percent over the 2021–2025 period.

There are two reasons the bureaucrats expect better economic performance if Obamacare is repealed. First, people will have more incentive to work because of a reduction in handouts.

CBO and JCT estimate that repealing the ACA would increase the supply of labor and thus increase aggregate compensation (wages, salaries, and fringe benefits) by an amount between 0.8 percent and 0.9 percent over the 2021–2025 period. …the subsidies and tax credits for health insurance that the ACA provides to some people are phased out as their income rises—creating an implicit tax on additional earnings—and those subsidies, along with expanded eligibility for Medicaid, generally make it easier for some people to work less or to stop working.

Second, the analysis also recognizes that there would be positive economic results from repealing the tax hikes in Obamacare, especially the ones that exacerbate the tax code’s bias against saving and investment.

Implementation of the ACA is also expected to shrink the capital stock, on net, over the next decade, so a repeal would increase the capital stock and output over that period. In particular, repealing the ACA would increase incentives for capital investment, both by increasing labor supply (which makes capital more productive) and by reducing tax rates on capital income. …repealing the ACA also would eliminate several taxes that reduce people’s incentives to save and invest—most notably the 3.8 percent tax on various forms of investment income for higher-income individuals and families. The resulting increase in the incentive to save and invest—relative to current law—thus would gradually boost the capital stock; consequently, output would be higher.

And here’s the most important table from the report. And it’s important for a reason that doesn’t get sufficient attention in the report, which is the fact that repeal of Obamacare will reduce the burden of spending and the burden of taxation. I’ve circled the relevant numbers in red.

Returning to something I touched on earlier, the CBO report gives inordinate attention to the fact that there’s a projected increase in red ink because the burden of spending doesn’t fall as much as the burden of taxation.

My grousing about CBO’s deficit fixation is not just cosmetic. To the extent that the report has bad analysis, it’s because of an assumption that the deficit tail wags the economic dog.

Here’s more of CBO’s analysis.

Although the macroeconomic feedback stemming from a repeal would continue to reduce deficits after 2025, the effects would shrink over time because the increase in government borrowing resulting from the larger budget deficits would reduce private investment and thus would partially offset the other positive effects that a repeal would have on economic growth. …CBO and JCT…estimate that repealing the act ultimately would increase federal deficits—even after accounting for other macroeconomic feedback. Larger deficits would leave less money for private investment (a process sometimes called crowding out), which reduces output. …The same macroeconomic effects that would generate budgetary feedback over the 2016–2025 period also would operate farther into the future. …the growing increases in federal deficits that are projected to occur if the ACA was repealed would increasingly crowd out private investment and boost interest rates. Both of those developments would reduce private investment and thus would dampen economic growth and revenues.

Some of this is reasonable, but I think CBO is very misguided about the importance of deficit effects compared to other variables.

After all, if deficits really drove the economy, that would imply we could maximize growth with 100 percent tax rates (or, if JCT has learned from its mistakes, by setting tax rates at the revenue-maximizing level).

To give you an idea of why CBO’s deficit fixation is wrong, consider the fact that its report got a glowing review from Vox’s Matt Yglesias. Matt, you may remember, recently endorsed a top tax rate of 90 percent, so if he believes A on fiscal policy, you can generally assume the right answer is B.

Here’s some of what he wrote.

Let us now praise Keith Hall. …his CBO appointment was bound up with a push by the GOP for more “dynamic scoring” of tax policy. …Yet today Hall’s CBO released its first big dynamic score of something controversial, and it’s … perfectly sensible.

Yes, parts of the report are sensible, as I wrote above.

But Matt thinks it’s sensible because it focuses on deficits, which allows his side to downplay the negative economic impact of Obamacare.

…the ACA makes it less terrible to be poor. By making it less terrible to be poor, the ACA reduces the incentive to do an extra hour or three at an unpleasant low-wage job in order to put a little more money in your pocket. CBO’s point is that when you do this, you shrink the overall size of GDP and thus the total amount of federal tax revenue. …The change…is big enough to matter economically (tens of billions of dollars a year are at stake) but not big enough to matter for the world of political talking points where the main question is does the deficit go up or down.

Yes, you read correctly. He’s celebrating the fact that people now have less incentive to be self-reliant.

Do that for enough people and you become Greece.

P.S. On a totally different topic, it’s time to brag about America having better policy than Germany. At least with regard to tank ownership.

I’ve previously written about legal tank ownership in the United States. But according to a BBC report, Germans apparently don’t have this important freedom.

The Panther tank was removed from the 78-year-old’s house in the town of Heikendorf, along with a variety of other military equipment,

including a torpedo and an anti-aircraft gun, Der Tagesspiegel website reports. …the army had to be called in with modern-day tanks to haul the Panther from its cellar. It took about 20 soldiers almost nine hours to extract the tank… It seems the tank’s presence wasn’t much of a secret locally. Several German media reports mention that residents had seen the man driving it around town about 30 years ago. “He was chugging around in it during the snow catastrophe in 1978,” Mayor Alexander Orth was quoted as saying.

You know what they say: If you outlaw tanks, only outlaws will have tanks.

I’m also impressed the guy had an anti-aircraft gun. The very latest is self defense!

I’m also impressed the guy had an anti-aircraft gun. The very latest is self defense!

And a torpedo as well. Criminals would have faced resistance from the land, air, and sea.

If nothing else, he must have a big house.

One that bad guys probably avoided, at least if they passed the famous IQ test for criminals and liberals.