About one year ago, Scott Hodge authored a report explaining the mechanics and utility of the Tax Foundation’s Taxes and Growth Dynamic Model. He made a very persuasive argument about the need to modernize and improve the Joint Committee on Taxation’s antiquated revenue-estimating process by estimating the degree to which changes in tax policy impact economic performance. The use of “dynamic scoring,” Scott explained, would produce more accurate data than “static scoring,” which is based on rather bizarre and untenable assumption that the economy’s output is unaffected by taxation.

Conventional scoring treats this process as an exercise in arithmetic, whereas dynamic scoring makes the process an exercise in economics.

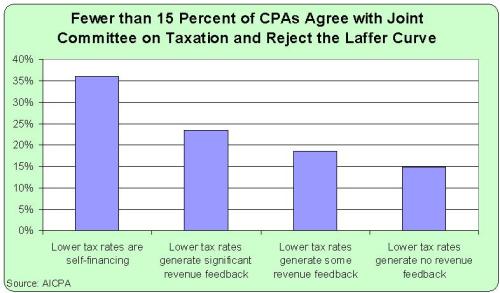

Since I’m a proponent of the Laffer Curve, I obviously applaud the Tax Foundation’s superb work on this issue.

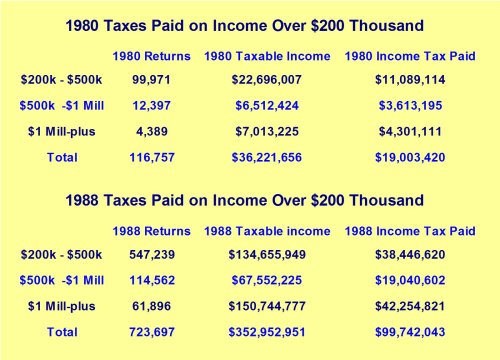

And for those who doubt the value of dynamic scoring, I challenge them to come up with an alternative explanation for why rich people paid five times as much tax after Reagan lowered the top tax rate from 70 percent to 28 percent in the 1980s.

But the Laffer Curve isn’t the focus of today’s column. Instead, I want to address the argument that supply-side tax policy (i.e., lower marginal tax rates, less tax bias against saving and investment) is no longer important or desirable.

Writing for Slate, Reihan Salam argues that Donald Trump’s success is a sign that the traditional tax-cutting agenda no longer is relevant.

Why can’t his GOP opponents convince Republican voters that they would do a far better job than Trump of defending middle-class economic interests? …Trump has demonstrated its weakness and the failure of its stale policy agenda to resonate with voters. …The GOP can no longer survive as the party of tax cuts for the rich. …If Republicans are to win the trust of working- and middle-class voters who’ve grown deeply skeptical of their economic nostrums, they will have to do something dramatic: It’s time for the GOP to abandon its near-obsessive devotion to tax cuts that disproportionately benefit upper-income households. …The GOP elite has also yet to grasp that most voters simply don’t care as much about taxes as they did in the Reagan era. …the share of voters who consider their federal tax burden their top priority is a mere 1 percent. To break out of their tax trap, Republicans…should continue to back tax cuts for the middle class, and in particular for middle-class parents. But until the country sees large and sustained budget surpluses, there should be no tax cuts for households earning $250,000 or more.

I’m not an expert on politics, so I won’t pretend to have any insight on whether tax policy motivates voters. But from an economic perspective, assuming the goal is a faster-growing economy that creates broadly shared prosperity, it would be very unfortunate if Republicans abandoned supply-side tax policy.

In the Tax Foundation study, Scott succinctly summarized the issue.

The primary goal of comprehensive tax reform is economic growth. …It is critically important that lawmakers make the right choices that lift everyone’s standards of living.

And here’s what I recently wrote, specifically addressing the assertion that proponents of good policy simply want to help the “rich.”

…It’s not that we lose any sleep about the average tax rate of successful people. We just don’t want to discourage highly productive investors, entrepreneurs, and small business owners from doing things that result in more growth and prosperity for the rest of us.

But what are those “right choices” that “result in more growth and prosperity for the rest of us”?

The Tax Foundation points us in the right direction. Let’s look at some charts (updated versions of the ones in Scott’s report), starting with this estimate of how various tax cuts affect overall economic output.

As you can see, expanded child credits don’t have any positive impact on growth for the simple reason that they don’t alter incentives to work, save, or invest (they may be desirable for other reasons, however). Lower marginal tax rates lead to some added growth, particularly if the top rate is reduced since upper-income taxpayers have far greater control of the timing, level, and composition of their income. But the biggest growth effects come from lowering the corporate tax rate and reducing the tax code’s bias against new investment.

Now let’s take the next step.

If changes in tax policy lead to increases in economic output, that also means a greater amount of taxable income.

So the Tax Foundation also can tell us the degree to which the aforementioned tax cuts will change revenue after 10 years. As you can see, most tax cuts result in less revenue, but in some cases there’s a considerable amount of revenue feedback. And if policy makers shift toward expensing, the long-run effect is more tax revenue.

Now let’s look from the other perspective.

What happens to the economy if various tax hikes are imposed?

As you can see, some tax increases have relatively modest effects on economic output while others significantly discourage productive behavior.

And when you feed the growth effects back into the model, you then can see the likely real-world effect of those tax increases on tax revenue.

So if policy makers impose a relatively benign tax hike, such as scaling back the state and local tax deduction, they will collect a considerable amount of revenue. But if they increase top tax rates on personal income or corporate income, a lot of the projected revenue evaporates. And if they exacerbate the tax bias against new investment, the net effect is less revenue.

By the way, these charts show why the class-warfare tax policies of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders are so misguided. The amount of economic damage per dollar collected would be ridiculous.

Such tax increases wouldn’t be good for rich people, of course, but the real lesson is that the rest of us will be adversely affected because of a slower-growing economy.

The bottom line is that poor people and middle-class people have much more opportunity and prosperity with a Hong Kong-style tax system instead of a punitive French-style tax system.

To conclude, let’s now consider a few caveats.

If you examine the broad measures of what causes prosperity, tax policy is just one piece of the puzzle. The burden of government spending also is important, as is trade policy, regulatory policy, monetary policy, property rights, and the rule of law.

So it’s possible for a nation to be relatively prosperous with bad tax policy so long as it has free-market policies in other areas. It’s also possible for a nation with a good tax system to be poor and stagnant if other economic policies are statist and interventionist.

But if the goal is faster growth and more broadly shared prosperity, why not seek good policy in all areas?

The bottom line is that supply-side tax policies can contribute to better economic performance. In an ideal world, those policies also are politically popular. But even if they aren’t, the policy-making community should strive to educate the populace on what works, not abandon good policy for the sake of short-term political expediency.

P.S. Even international bureaucracies acknowledge the Laffer Curve, which means they understand that changes in tax policy can lead to changes in taxable income.

- Such as this study from the OECD acknowledging that lower tax rates can lead to more taxable income.

- Or this study by the IMF, which not only acknowledges the Laffer Curve, but even suggests that the turbo-charged version exists.

- Or this European Central Bank study showing substantial Laffer-Curve effects.

- Or the United Nations admitting that the Laffer Curve limits the feasible amount of taxes that can be imposed.

legislation) was going to raise about $50 million every three months.

legislation) was going to raise about $50 million every three months.