I’ve written a few columns that explain tax principles, but this video from the Tax Foundation may be the best place to start if you have friends or colleagues who need to learn the basics.

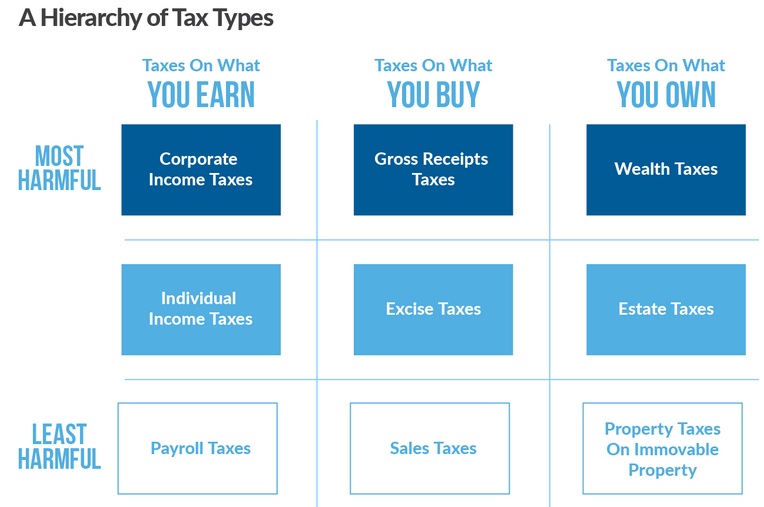

As part of the article that accompanies the video, the Tax Foundation explains that not all taxes are created equal. In other words, some taxes impose more damage than other taxes.

And this chart from the article is a nice summary of the three types of tax, along with the potential damage caused by varying ways of collecting tax.

As a general rule, this chart is totally accurate.

Corporate income taxes, gross receipts taxes (mentioned here), and wealth taxes do a lot of economic damage on a per-dollar-collected basis.

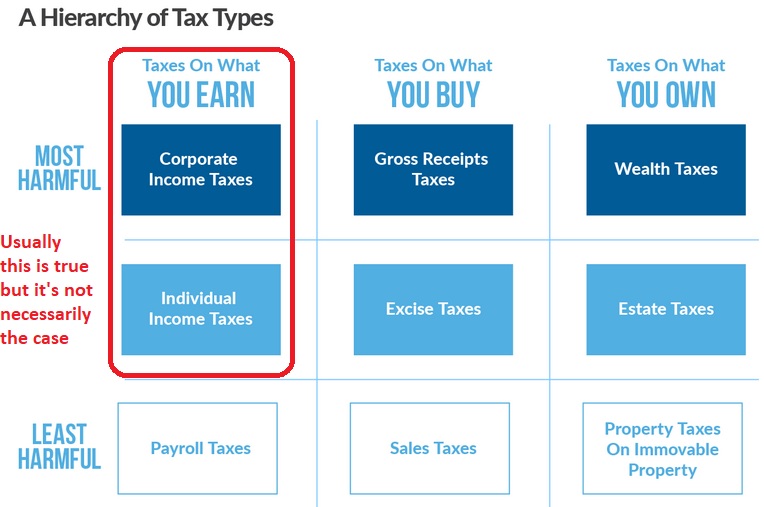

But I want to add a caveat to the first column.

As currently designed, there’s no question that the personal income tax and the corporate income tax are very bad taxes.

But it is possible to dramatically reduce the damage imposed by those levies. For instance, the personal income tax could be largely defanged if the current system was repealed and replaced by a simple and fair flat tax.

Likewise, it’s possible to reform the corporate income tax (full expensing, territoriality, no double tax on dividends, etc) so that it does comparatively little damage.

By the way, I’m sure the experts at the Tax Foundation would agree with these observations, so I’m augmenting rather than criticizing.

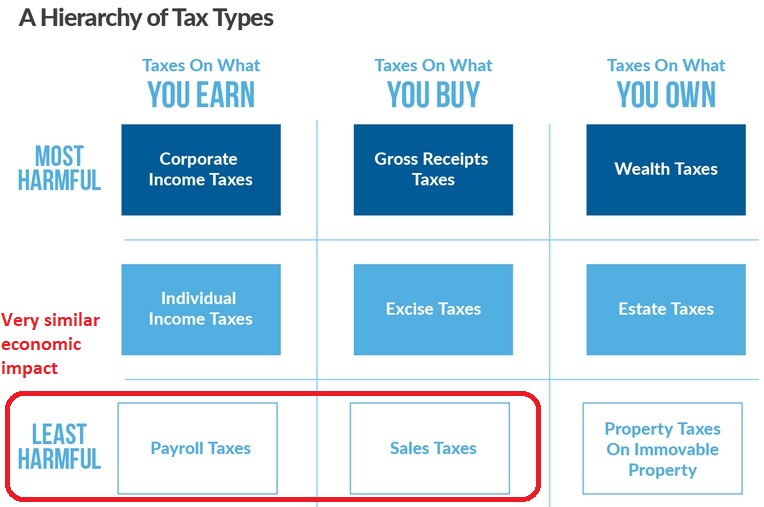

And since I’m doing some augmenting, another observation is that the first two taxes on the bottom row generally are very similar, at least with regard to their economic impact (and also similar to a properly designed individual income tax).

Here’s some of what I wrote in a column back in 2012.

…anything that expands the “tax wedge” between pre-tax income and post-tax consumption is going to impose similar levels of economic harm. Here’s a simple example. If I earn $100, does it matter to me if the government takes $25 as I earn that income (either with a payroll tax or income tax) or as I spend that income (either with a sales tax or value-added tax)? Is there any reason that my incentives to earn and produce will be altered by shifting from one approach to the other?

I explain that the answer is no. My incentive to earn income is affected by my ability to use income to enjoy consumption. But if taxes take a big bite, I’ll have less reason to be productive, regardless of how politicians collect the tax.

For what it is worth, I’ve used Belgium as an example to explain why shifting from payroll taxes to sales taxes, or vice-versa, is not a recipe for greater prosperity.

P.S. Those who want more advanced primers on taxes and growth should click here and here.

This last point is important because Italian politicians are actually considering proposals to either levy a temporary property tax or a temporary tax on all assets, supposedly for the purpose of reducing the nation’s debt.

This last point is important because Italian politicians are actually considering proposals to either levy a temporary property tax or a temporary tax on all assets, supposedly for the purpose of reducing the nation’s debt.