Last November, I wrote about the lessons we should learn from tax policy in the 1950s and concluded that very high tax rates impose a very high price.

About six months before that, I shared lessons about tax policy in the 1980s and pointed out that Reaganomics was a recipe for prosperity.

Now let’s take a look at another decade.

Amity Shlaes, writing for the City Journal, discusses the battle between advocates of growth and the equality-über-alles crowd.

…progressives have their metrics wrong and their story backward. The geeky Gini metric fails to capture the American economic dynamic: in our country, innovative bursts lead to great wealth, which then moves to the rest of the population.

Equality campaigns don’t lead automatically to prosperity; instead, prosperity leads to a higher standard of living and, eventually, in democracies, to greater equality. The late Simon Kuznets, who posited that societies that grow economically eventually become more equal, was right: growth cannot be assumed. Prioritizing equality over markets and growth hurts markets and growth and, most important, the low earners for whom social-justice advocates claim to fight.

Amity analyzes four important decades in the 20th century, including the 1930s, 1960s, and 1970s.

Her entire article is worth reading, but I want to focus on what she wrote about the 1920s. Especially the part about tax policy.

She starts with a description of the grim situation that President Harding and Vice President Coolidge inherited.

…the early 1920s experienced a significant recession. At the end of World War I, the top income-tax rate stood at 77 percent. …in autumn 1920, two years after the armistice, the top rate was still high, at 73 percent. …The high tax rates, designed to corral the resources of the rich, failed to achieve their purpose. In 1916, 206 families or individuals filed returns reporting income of $1 million or more; the next year, 1917, when Wilson’s higher rates applied, only 141 families reported income of $1 million. By 1921, just 21 families reported to the Treasury that they had earned more than a million.

Wow. Sort of the opposite of what happened in the 1980s, when lower rates resulted in more rich people and lots more taxable income.

But I’m digressing. Let’s look at what happened starting in 1921.

Against this tide, Harding and Coolidge made their choice: markets first. Harding tapped the toughest free marketeer on the public landscape, Mellon himself, to head the Treasury. …The Treasury secretary suggested…a lower rate, perhaps 25 percent, might foster more business activity, and so generate more revenue for federal coffers. …Harding and Mellon got the top rate down to 58 percent. When Harding died suddenly in 1923, Coolidge promised to “bend all my energies” to pushing taxes down further. …After winning election in his own right in 1924, Coolidge joined Mellon, and Congress, in yet another tax fight, eventually prevailing and cutting the top rate to the target 25 percent.

And how did this work?

…the tax cuts worked—the government did draw more revenue than predicted, as business, relieved, revived. The rich earned more than the rest—the Gini coefficient rose—but when it came to tax payments, something interesting happened. The Statistics of Income, the Treasury’s database, showed that the rich now paid a greater share of all taxes. Tax cuts for the rich made the rich pay taxes.

To elaborate, let’s cite one of my favorite people. Here are a couple of charts from a study I wrote for the Heritage Foundation back in 1996.

The first one shows that the rich sent more money to Washington when tax rates were reduced and also paid a larger share of the tax burden.

And here’s a look at the second chart, which illustrates how overall revenues increased (red line) as the top tax rate fell (blue).

So why did revenues climb after tax rates were reduced?

Because the private economy prospered. Here are some excerpts about economic performance in the 1920s from a very thorough 1982 report from the Joint Economic Committee.

Economic conditions rapidly improved after the act became law, lifting the United States out of the severe 1920-21 recession. Between 1921 and 1922, real GNP (measured in 1958 dollars) jumped 15.8 percent, from $127.8 billion to $148 billion, while personal savings rose from $1.59 billion to $5.40 -billion (from 2.6 percent to 8.9 percent of disposable personal income). Unemployment declined significantly, commerce and the construction industry boomed, and railroad traffic recovered. Stock prices and new issues increased, with prices up over 20 percent by year-end 1922.8 The Federal Reserve Board’s index of manufacturing production (series P-13-17) expanded 25 percent. …This trend was sustained through much of 1923, with a 12.1 percent boost in GNP to $165.9 billion. Personal savings increased to $7.7 billion (11 percent of disposable income)… Between 1924 ‘and 1925 real GNP grew 8.4 percent, from $165.5 billion to $179.4 billion. In this same period the amount of personal savings rose from an already impressive $6.77 billion to about $8.11 billion (from 9.5 percent to 11 percent of personal disposable income). The unemployment rated dropped 27.3 percents interest rates fell, and railroad traffic moved at near record levels. From June 1924 when the act became law to the end of that year the stock price index jumped almost 19 percent. This index increased another 23 percent between year-end 1924 and year-end 1925, while the amount of non-financial stock issues leapt 100 percent in the same period. …From 1925 to 1926 real GNP grew from $179.4 billion to $190 billion. The index of output per man-hour increased and the unemployment rate fell over 50 percent, from 4.0 percent to 1.9 percent. The Federal Reserve Board’s index of manufacturing production again rose, and stock prices of nonfinancial issues increased about 5 percent.

Now for some caveats.

I’ve pointed out many times that taxes are just one of many policies that impact economic performance.

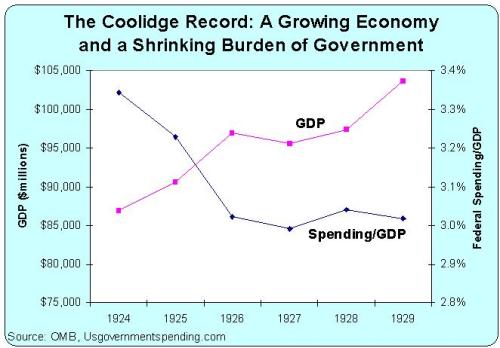

It’s quite likely that some of the good news in the 1920s was the result of other factors, such as spending discipline under both Harding and Coolidge.

And it’s also possible that some of the growth was illusory since there was a bubble in the latter part of the decade. And everything went to hell in a hand basket, of course, once Hoover took over and radically expanded the size and scope of government.

But all the caveats in the world don’t change the fact that Americans – both rich and poor – immensely benefited when punitive tax rates were slashed.

P.S. Since Ms. Shlaes is Chairman of the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, I suggest you click here and here to learn more about the 20th century’s best or second-best President.

P.P.S. I assume I don’t need to identify Coolidge’s rival for the top spot.